Excerpt: Qiu Miaojin’s Notes of a Crocodile (original) (raw)

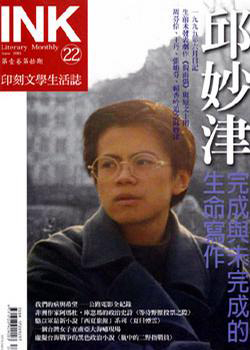

Qiu Miaojin—one of the first openly lesbian writers in ’90s post-martial-law Taiwan—committed suicide at the age of 26. What follows is an excerpt from her “survival manual” for a younger generation. With an introduction by translator Bonnie Huie.

Photos by Ahmad Haifeez Kamarudin.

The first book that I was ever asked to translate was a debut collection of short prose by a young Taiwanese writer that I knew. Proceeding with no real experience (or methodology), it seemed natural to glean a more objective view of her by asking the question: Who are your biggest influences? I carefully looked up each author on her list, poring over the biographical notes, until I came to the name Qiu Miaojin and discovered that she was one of the first openly lesbian writers in ’90s post-martial-law Taiwan. Her suicide in 1995 at the age of twenty-six had transformed her, a relatively obscure writer, into a household name. I was curious. Who was she? What was her writing like? The consensus, it seemed, was that this woman had done something heroic. I could only imagine a confessional style—but this sounded more experimental, more transgressive, and a little wiser. These kinds of mysterious details are like blood on paper, traces of real-life suffering that one can’t help reading into the work. At the completion of the aforementioned translation project, I received a gift from the author, a set of books in Chinese, including a copy of the novel that was to become my next translation project. That novel was Qiu’s Notes of a Crocodile_._

(INK Literary Monthly)

Notes of a Crocodile is a very special book within Qiu’s oeuvre (which consists of three novels, a collection of short stories, a play, and her diaries). While Qiu’s final novel, Letters from Montmartre_, is widely considered to be more sophisticated,_ Notes is a classic in its own right, a more accessible work that posthumously won her the China Times Honorary Prize for Literature in 1995. Its narrator claims that the eight notebooks comprising Notes have been culled from personal diaries in order to provide a survival manual for a younger audience. Occupying a world outside the social domains of heteronormativity, the narrator confronts the nature of dualities as she tangles with characters like Meng-Sheng, a fellow writing workshop participant whose arrogant personality she initially can’t stand: “When I hung out with him, the masculine and feminine within me were in their fiercest state of dialectical tension. It was the same for him, and what’s more, he knew it was the optimal state.” We can see this preoccupation with dualities, too, in the narrative’s philosophical turns. (“It dawned on me one day, as if I were writing my own name for the very first time: cruelty and mercy are in fact one and the same.”) If Notes of a Crocodile contains lessons, they may just as well be about human nature as about literary form. You don’t have to be just one thing, Qiu seems to be saying, and if you are to become a truly empathetic individual, you cannot allow yourself to perceive others as such. –Bonnie Huie

Notebook #3

September. I’d been living on Heping East Road for two months. My cousins had to start getting ready for entrance exams, and so it was hinted that I should go somewhere else. I had to move out. I quickly found an attic bedroom on Tingzhou Road, an empty space on the top floor. Aside from a crude toilet, sink, and old-fashioned water boiler, there was only a narrow slit of a room in which my roommate, a woman with a strangely shaped face, lived. She was about twenty-five or twenty-six. Worked in a factory. My impression of her was that sometimes she’d borrow money from me and never pay me back. She liked to knock on my door to probe me about the college student lifestyle, or personal matters like my romantic history. What’s more, there was a guy who was always broke, who’d come over in the middle of the night and stay over. He always walked around naked with a cigarette dangling out of his mouth. He’d yank her to the ground and beat her with a whip or a shoe, dragging her outside, all the way over to the plaza. But when she talked about him with me, a happy glow spread across her face. She said he was the only one who didn’t despise her.

Living on the top floor, it was hot as an oven until nightfall. Around ten o’clock, I’d go home and immediately lock the door behind me, terrified by the thought of the two of them together on a dark and stormy night. It was as though the souls of a pair of prisoners dying a slow death were breaking down the door to my room. Hence the feeling of living under the same roof with people you don’t know, which might easily be forgotten—this is what ultimately built the tomb for my practice of pure solitude.

Daytime. As soon as the alarm sounded, I’d leap out of bed and “go to work” for my club. Didn’t wash my face, didn’t brush my teeth. Had to practically fly on my bike to campus. It was as if I’d made an appointment with colleagues and was rushing documents to this extracurricular organization, or preparing for a noontime meeting. Even designing the promotional fliers, sending mailers, organizing archives, or running any type of errand might be of the utmost importance, though there was never enough time to handle the bulk of it. You had to treat it like a boring game by acting serious and earnestly focusing on the matter at hand. It amounted to self-motivation through a theoretical earnestness. This is what entering society and the workforce would be like in the future. This having been decided, if you wanted to move up, you had to play the game on a sophisticated level, and with excitement. Otherwise you’d lose your passion a little. Get muddled. Gradually descend into a voluntary state of meaninglessness.

Almost completely lost track of schoolwork. My gym teacher wanted to murder me. I heard the news that the military drill instructor was looking everywhere for me and “wanted to see me in his office.” Buried my head in the sand. I was about to fail half or even two-thirds of my credits, which would flunk me out of school. To an ordinary person, this particular shift to a value system that meant actually having a life was symbolic of a future roadmap with deteriorating hopes. I was throwing away my life. It was like hammering a steel axle through a spinning top, so that it would automatically spin on a fixed point on the ground. Though it was automated, in reality it was aimless, all meaning was lost. Eagerly hurrying off to attend to student organization affairs, I worked to my heart’s content straight up until 10 o’clock in the evening, when I went home. It became my steel axle, spinning faster and faster, to the point where it was unstoppable. After I got home, I’d habitually open a beer and drink myself into a stupor, and basically kill time until my alarm went off the next morning.

Chu-Kuang. He could see the emptiness that was concealed beneath my excesses of energy and enthusiasm. He was three years older than me and the club representative of the organization next to mine. The two of us shared the same student organization office and his desk was next to mine. His hairline was receding. The back and the top, which formed the central portion, had likewise managed to become a reflective patch. He was heavyset, with his lower half forming the girth of a triangle. He always wore the same pair of purple and green denim pants threaded with a thin gold belt, like a nightclub host. Or perhaps it was the complete opposite, that he appeared to have just emerged from the depths of poverty, his t-shirt crumpled like toilet paper. The portion below those baggy, knee-length pants exposed the two hairy legs that hauled around puffy eyes hidden behind a pair of sunglasses.

Without fail, at 8 or 9 in the evening, it was only the two of us who were still “at the office.” Or perhaps on most days the two of us were performing, simultaneously exaggerating and showing off. When there was no one for us to perform or show off for, every once in a while, I’d look up and glance over at him, and smiles would spread across both our faces in a moment of clear mutual understanding. Then, as if in unspoken agreement, we would both turn back to our work. My impression of this cooperative order between bat-like creatures was gradually evolving into a positive one.

“Hey, what are you doing?” I had just folded 30 copies of a meeting announcement. I asked moodily.

“Sketching a layout.” His organization put out a weekly newsletter. He lowered his head.

“Hello? What are you doing again?” I said playfully, bored to death. I had to ask again.

“Making an illustration.” He lowered his head even further. The tip of his nose was practically touching the paper.

“Hello?! What’s that you’re still doing over there?” I watched him motionless, as if lost in his work, which made it even more amusing.

“You little rascal!” Summoning all his strength, he set down his pen, pried his eyes away from the page, and stood up. He opened his eyes wide and threw me a ferocious glare, then walked over and squeezed my chin in one of his giant hands. “Not afraid to die, huh? Gotta disturb me?”

I thought of him as a man-shaped mountain, something you could step on for amusement. To have a little, witty cartoon-style exchange. Having shared an office for quite some time, I had collected through observation a wealth of data about my counterpart, who had become a potential screen upon which images were projected. When we both ventured behind that screen, we would engage in a pointed conversation that was, in reality, set. Indeed, it evolved into something like a taboo. The two of us were both engrossed by the diversions of shadow play, which were better than getting to know a real human being.

“You look like shit today.” Through all the people sitting between us, and amidst the noontime deliveries of documents. “There’s a hole in your lovely jeans. Mind your own business!” Conversing with an upperclassman at the same time. More documents being delivered.

“Your eyes are puffy. You didn’t rub them, did you? Just crawled out of the sewer?” Another document.

“People who have no eyeballs and lie around in a sewer all day need to shut up.” Peeking over at him. Continued talking.

“If you keep crawling out of the sewer and straining yourself laughing while keeping those bloodshot eyes open, you’re going to die an early death.” This time the document was tossed straight at me. Standing next to him was a group that was talking about business. The two of us had taken a break from work to bare our fangs at one another.

It was the school’s anniversary. Got trapped in a festival all day, running around and shouting. At dusk, the crowds were about to disperse. Heading up to the second floor of the recreation center, I felt like hanging my limp body from a bamboo pole. Clustered outside the office was a group of people, like monkeys that wouldn’t give up trying until they found a way to get inside. At the foot of the door sat Chu-Kuang’s deputy club representative. Exhausted, he stretched out his legs and announced that everyone needed to clear the area. In the office, someone was having some kind of issue, and had locked themselves inside.

I pushed to the front and pounded hard on the door.

“Chu-Kuang, open the door and let me in. I have to talk to you.” Those words. I had no idea where they came from. It was like mining some kind of oil field of feelings. From inside was the sound of a certain shadow unlocking the door. The deputy club rep stared at me in amazement. I ducked through the narrow crack that emerged, and immediately locked the door behind me.

“What happened?” I fumbled around for a chair, then finally sat next to him on the chair. I crossed my legs and asked gently. The shades of the office windows were lowered. It was secretly used as a projection room for movies. His forehead was glistening in the hazy light.

“Little sister…can you go buy me a drink? And listen to what I have to say…” He held his face in his giant hands. His head rested on the desk.

A sigh of despair. He was like a gentle creature speaking in a pleading tone.

“Why do you want to talk to me?” I kept one eye on the reddish light at dusk, which streamed in through the window behind him.

“Meng-Sheng…it’s because you know Meng-Sheng, too. He’s the link between us…” I heard him say. Went and bought a 12-pack of beer plus two packs of cigarettes, and picked up some marinated takeout dishes along the way. Sent away the deputy club rep and the crowd hanging around outside. The whole carnival was still raging on. The sound of someone practicing the piano pierced the air, then evaporated into the mix.

“This afternoon Meng-Sheng came over…he was looking for you…it’s just that we got into a fight…”

“You had a spat with Meng-Sheng?”

“What do you mean, had a spat? I still want to eat the guy alive, rip the flesh from his bones.” Chu-Kuang stopped and raised his head. There was a blood stain running from his nose to the corner of his eye. From the lower row of his teeth, there was a tooth missing. He downed the entire can of beer in one gulp. “Would you ever imagine that a fight between lovers could end like this? Hey, too much passion. As soon as I saw him coming, he said he was looking for you, and I flew off the handle. Snatched a metal ruler off the table and started thrashing him with it. He wouldn’t give up. Like a man possessed, he grabbed a metal chair and started whacking me with it. It was like the two of us were doing the cha-cha… Hey, I remember vividly his impeccable fighting techniques and the smell of his sweat.” He smiled amusedly.

“The second you see each other, you start to fight. Would you call that love or vengeance?”

“Didn’t Hsia Yü have a poem called ‘Sweet Revenge’? I only mention it because I thought you might have heard of it. It’s like the title of the poem. Because mutual love means vengeance, and because it’s vengeance, you’re going to fight, and because you’re fighting, it’s mutual love. It’s a combination of those three things. It’s like if the intensity of lust reaches a certain level of frustration, and the fixation of that lust isn’t cast off by release or eradication, the void of nothingness isn’t removed, and it never attains the lightness of air. Much the opposite, it only increases suicidal despair and attachment to the object of lust. At that point, the body thoroughly assimilates it through the death wish. In the very beginning, I was self-destructive. My lust was simply assimilated, and never found its way out. That’s the scariest thing. There was one day when it suddenly flared up, and I grabbed a pair of scissors and began stabbing myself. That was something that happened before Meng-Sheng and I broke up. Before that, I learned to lower the scissors and give part of my destructiveness to Meng-Sheng. There was no cure. I still longed to be with him. The love I had stored burned away, and all that remained was a fire that he could put out. It brought about all kinds of connections.”

“Meng-Sheng told me that he saved some guy’s life. Was it you?”

“Ha! Is that what he told you? So then did he tell you all about his sexual relationship with that guy?” He stopped abruptly. His shoulders slumped as if he had said something wrong and wanted to apologize.

“I don’t want to get in the middle of your dogfight and become the raggedy old towel against your aching jaw. If you want to say it, just say it. I’m not even trying to dig out your secrets here. And if I had to swallow the bitterness of your past experiences, my stomach wouldn’t rot, and I wouldn’t vomit, either. Whatever it is you have to say, as long as it flows like the juices of your brain, it should be fine. So it turns out that this is the kind of person you are!” His convoluted expression made me want to smear ink on his face.

“It’s normally considered pretty vulgar to say these kinds of things to a girl.”

“If you think you’re going to be vulgar, then you don’t have to say anything. I wouldn’t want to be your personal minister of information.”

“Aw, little sister, you’re really something special. Yeah, that’s exactly what you are. There’s never been a single person who, after I bring up this part of the relationship between me and him, doesn’t completely change their facial expression or start squirming in their chair. Most people automatically avoid me. There were only one or two who put on a straight face and went to the trouble of staying in touch with me. I always laughed to myself about that, because why bother showing off when it’s that painful to force yourself to display your generosity? Besides, you’re a girl, although you’ve listened to me tell you this much, and it’s like you’re listening to me talk about growing callouses on the bottom of my feet…”

“How long have you been in love with Meng-Sheng?”

“In all, about four years. That’s on my part. Him, all of these last five years. After I figured out that he transferred his desire for women onto me, can I even say that he loved me for more than half a year? He’s like, every cell in his body is evil. He’s a complete and total thug.”

“Chu-Kuang, listen to me. When you’re with me, I just want you to genuinely be yourself. I know it’s really difficult. The bottoms of my feet might be calloused, too, but I wasn’t prepared to have this conversation. Can you do that?”

Without us realizing it, it was almost 10 o’clock. Outside the recreation center, all around campus, the festival was still lively. A heavy metal band played, lasers pointing in all directions as drunken students bid farewell to their wanton desires.