The Hart Kidnapping and Midnight Lynching (original) (raw)

I knew Alex J. Hart; he was a customer in my Los Gatos antiques store and longtime friend of my late husband’s mother. Mr. Hart was the epitome of a gentleman, with elegance and class, Mr. Panache, I called him—and he always smiled his inimitable, shy smile. I recently learned that he died last August, just shy of 90. Alex Hart had achieved a sad kind of fame at thirteen—a fame that put his family on banner headlines of America’s front pages. He was the younger brother of Brooke Hart who was kidnapped and killed on November 9, 1933 for ransom; an angry crowd of San Jose townspeople, still raw after the Lindbergh baby kidnapping—publicly lynched the two captors.

The kidnappers had demanded $40,000 for his safe return, an enormous sum during the Great Depression, even after they had already murdered Brooke within an hour of the abduction. They had watched his movements for weeks and snatched him at the parking garage behind Hart’s Department Store, then drove him ten miles south to a rural road, switched cars and took him to the San Mateo Bridge.

In the days before San Jose’s urban sprawl and shopping malls, Hart’s Department store, at the corner of Market and Santa Clara Streets, was a retail giant where everyone shopped, where everyone knew and everyone loved the Hart family. The Hart kidnapping was to become a California landmark case; when an angry mob seeking vigilante justice took vigorous action and lynched the pair of kidnappers at midnight from trees, swinging side by side, in San Jose’s St. James Park on a chilly November Sunday in 1933.

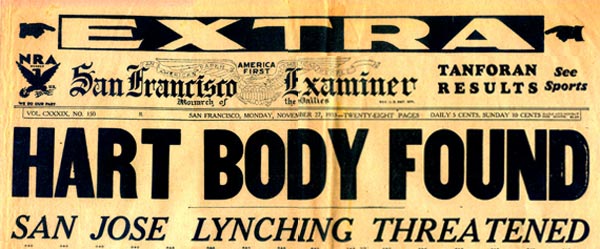

I had wanted to write of the historic lynching for a long time. I had saved yellowed newspapers for years. I perused the 1933 time-yellowed crumbling papers: San Jose News blared a banner headline HART KIDNAPPED; San Francisco Chronicle KIDNAPPERS KILL HART—Crime Confessed by Pair, Youth Bound, Tossed in Bay; The San Francisco Examiner blasted the boldest—HART BODY FOUND, San Jose lynching threatened—November 27.

Upon reading the actual November 1933 newspaper reports, unfiltered and undiluted, and not tinged with modern-day moral relativity opinion—reported in a time when political correctness, neutral attitudes and the use of alleged did not exist, it is clear how the media inflamed the crowds to become so bloodthirsty, so desirous of justice—albeit devoid of even a constitutional right to a fair trial. The Examiner’s headline about a threatened lynching was taken as a serious suggestion. Revisionists would argue otherwise. Radio stations broadcast the kidnapping and the captors’ confessions, announcing that angry mobs were seeking justice at the Santa Clara County jail across from St James Park—promising “to be broadcast as a ‘live’ event.”

There was never good reason for such deplorable extrajudicial action, but it must be understood that in 1933 during the Great Depression, there was intense economic stress in a period of unrest and disillusionment; people had no jobs or money and people were hurting, hungry and angry. They vented their simmering fury to a boiling point, four years into the country’s worst depression—the lynching may be seen as a social catharsis of taking control, and taking justice into their own hands with electric mob action galvanizing their sense of immediacy, camaraderie and potency.

Alex Hart, Sr., Brooke’s father, was one of San Jose’s most beloved business owners, having founded and operated the landmark Hart’s Department Store in 1902. The first 1866 operation started as a dry goods store in the Valley of Heart’s Delight. The Hart family was involved in the San Jose community and had generously supported many causes, including the later donation of their historic family home on The Alameda at Naglee to the YMCA. The Harts were a respected and well-known family in the Jewish and Catholic community—Alex was Jewish, his wife Nettie was Catholic. The kidnappers could not have chosen a more beloved high-profile family to target, as the public lynching so dramatically had demonstrated by the citizens’ collective wrath.

Brooke Hart had graduated from Bellarmine College Preparatory and Santa Clara University—his parents supported school programs and knew everybody. Brooke’s stunning good looks, athletic build, blond wavy hair and blue eyes added to his dashing popularity and ‘the town’s most eligible bachelor’ attracted the valley girls. “They went to Harts just to look at him…” Marie Venezia, four years younger than him, told me many years ago. “Everyone loved him, everyone was shocked…everyone wanted to go to the park…”

After Brooke graduated from SCU, he was groomed to head the family business. His father Alex Sr. never drove an automobile so Brooke bought a 1933 Studebaker Roadster to drive his dad to and from work. It was the same green roadster he was retrieving from the parking garage when the kidnappers grabbed him. No one ever saw the twenty-two year old man alive again. A phone call that night to the family home confirmed that their son was kidnapped. “We have your son; we want 40,000forhisreturn,drivethemoneytoLosAngelesandyouwillgethimback.”RansomnoteshadalsobeenmailedfromSacramentoandSanFranciscotosendthepoliceoffthetrack.Onenotedemandedthatthenumber1beplacedinHart’sstorewindowiftheyagreedtopayfortheirson’ssafereturn.Thekidnappersnonchalantlystrolledbythestoreandsawthesign,believingthe40,000 for his return, drive the money to Los Angeles and you will get him back.” Ransom notes had also been mailed from Sacramento and San Francisco to send the police off the track. One note demanded that the number 1 be placed in Hart’s store window if they agreed to pay for their son’s safe return. The kidnappers nonchalantly strolled by the store and saw the sign, believing the 40,000forhisreturn,drivethemoneytoLosAngelesandyouwillgethimback.”RansomnoteshadalsobeenmailedfromSacramentoandSanFranciscotosendthepoliceoffthetrack.Onenotedemandedthatthenumber1beplacedinHart’sstorewindowiftheyagreedtopayfortheirson’ssafereturn.Thekidnappersnonchalantlystrolledbythestoreandsawthesign,believingthe40,000 ransom money would be paid (millions by today’s standards), and the men waited it out.

The San Jose News printed an overture from the family on the front page on 14th November, 5 days after the kidnapping: “To the kidnappers of Brooke L. Hart, we are anxious for the return of our son Brooke. We desire to negotiate for his return personally through any intermediary who may be selected. When contact is made we will want evidence to prove Brooke is held by you. All negotiations will be considered confidential and we will allow no interference from outside sources; signed Alex J. Hart, Nettie Hart.”

Guards were placed in front of the family home and telephones were tapped. When Thurmond made calls from a hotel and a pay phone in a parking garage, police nabbed him. He squealed and fingered Holmes as his accomplice.

The details of the abduction, as confessed by the pair were reported by newspapers spelling out the gruesome scenario; Thomas Harold Thurmond and John M. Holmes had driven with Brooke from the San Jose garage around six o’clock on the 9th of November to rural Evans Road 10 miles south—now Milpitas—Holmes in the Studebaker with Brooke and Thurmond following. Brooke was transferred to the rear seat of a ‘long-hooded sedan’. A woman had seen them; the green roadster was in front of her house, lights still on—that night her husband reported the incident; the police now had proof that Brooke Hart was abducted.

The confession to interrogators by Thurmond and Holmes explained that as Brooke Hart was exiting the garage, Holmes opened the passenger door poking his hand in his pocket as if he had a gun. Thurmond followed and they drove to Evans Road, switched cars and drove through Irvington to the San Mateo Bridge. They asked Brooke for his wallet and split the $7.25 take. The kidnappers were prepared; Holmes had already bought a brick, two 22-lb concrete blocks and 55 cents worth of bale wire from a San Jose cement company.

“We planned the kidnapping for six weeks,” Holmes confessed. The town was shocked that two cold-blooded killers lived among them; Holmes had attended Lowell High School and lived on Bird Avenue with his wife and two children; Thurmond was a Campbell High School drop-out.

The kidnappers confessed that they drove to the San Mateo Bridge, bound Brooke Hart’s hands with bale wire up to his shoulders and attached the two cement blocks to sink him. Holmes beat his head with the brick, Brooke screamed for help, he hit him again and grabbed his upper body, Thurmond held the knees and they placed him on the railing. “He was still struggling when we threw him off the bridge; it was low tide so we shot him.” The shell casing was found but no bullet actually penetrated Brooke’s body, police reported. Thurmond returned to San Francisco and called at 9.30, then again at 10:30 for the ransom. The plan was not going well, they had told Alex Hart to drive to Los Angeles with the money. Alex Hart could not drive.

The San Jose community went berserk when the news first broke about the kidnapping; one of their own beloved citizens had been taken for ransom and then when they heard about the murder, anger erupted. Everyone knew the family; they all shopped at the store, the Harts were part of their town and besides, people were still raw from the recent kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby.

Radio news broadcast the plot, told of the death—stations in Los Angeles and San Francisco spurted retaliation and the media composed a mob. Reporters and camera operators flocked to the city of 60,000, newsreel cameras were set up in St James Park across from the Courthouse. It was to be a show of shows.

When the Hart family was informed on November 14th by the police about Brooke’s death, Mr. Hart collapsed to the floor—the family went into mourning. Guards were removed from The Alameda home. The City of San Jose went into shock.

Thurmond and Holmes signed confessions, each blaming the other, and were jailed in the Santa Clara County police station across from St James Park near the Courthouse on November the 14th. When angry crowds gathered in the park, the pair was to be sent to the San Francisco Potrero Hill police station. Searchers dragged the San Francisco Bay for the body, rewards were offered for his discovery. Then on November the 26th, seventeen days after the November 9th kidnapping, two Redwood City duck hunters found Brooke’s partially-dressed crab-eaten decomposing body south of the bridge. Radios blared that a lynching would take place in St James Park across from the Courthouse at 9:00 p.m. on that Sunday and would be broadcast ‘live’. Scores of reporters staked out positions, and by sundown over 5,000 people, including children, had gathered for the event.

The fury had been fueled all week when the Santa Clara County District Attorney advised that unless the confessions could be corroborated by independent evidence of the crime, the confessions were not admissible in a court of law, hinting the murderers may be innocent, hinting they may not get the death penalty. The Court required that the kidnappers be inspected by psychiatrists to possibly plead not guilty by reason of insanity. The crowds went berserk—they wanted blood. Sheriff William Erig requested that Governor Rolph deploy the National Guard to protect the prisoners. He refused. Agnew State Hospital sent their psychiatric experts to preclude the insanity defense and found the pair to be sane, able to stand trial. Holmes’ father paid San Francisco attorney Vincent Hallinan $10,000 to defend his son and he also asked the governor to send out the Guards. He refused again. “I will pardon the lynchers.” He said.

MIDNIGHT LYNCHING IN THE PARK

By the evening of Sunday the 27th November, the park crowd had swelled to an estimated 5,000; some reported 10,000. Over 3,000 cars, some with motors still running, jammed the surrounding streets. Near midnight the heated crowd was chanting “Lynch them, lynch the murderers…” The police fired tear gas into the crowd, thus inflaming their already boiling fury. People ran to the Post Office—now the San Museum of Art—to get materials for a battering ram. The police, unable to control the mob, sought safety in the higher floors; the prisoners were in cells below. The mob broke down the doors, stormed the jail, dragged the kidnappers to the park, strung them up—Holmes on the elm and Thurmond on the mulberry tree—and hanged them. Jackie Coogan, the precocious child star, Brooke’s school chum pulled one rope. The hanged men swung half naked from the trees, photographed by the press, their corpses taunted and sworn at—people jockeying for position to get a close view, onlookers wanting to be present at the midnight hanging, perceived as justice for the death of one of the city’s most beloved.

When I lived in San Jose, I saw photographs and had heard many firsthand accounts forty odd years after the lynching by those who were present in 1933, men who lived a generation or two before me—reminiscing in a matter-of-fact manner, as if it were a film on a screen, like an outdoor movie played in the dark park at a midnight show. “After midnight it was all over, and then everyone left and we walked home to Hobson Street…” For decades people boasted of their presence in the park that historic night—the night that vigilantes got justice, the night that people took collective control, the night that amplified their madness and put pre-hyper grown San Jose on the map of notoriety.

The newspapers blasted the story, doubling issues to 1.2 million. When images of the half-naked hanging men made the front pages, faces in the crowd were purposely smudged so as not to identify the perpetrators. There is no doubt that the lynching was a media-fueled event with inflammatory reporting, protecting those who murdered the kidnappers without a fair trial. I read the reports in the original 1933 editions, devoid of neutrality, devoid of unbiased opinion—it is clear that the lynching was not subtly orchestrated—it was blatant; yellow journalism at its best.

The elm and mulberry trees were later destroyed and removed by the City because souvenir hunters tore up the park ripping off branches, twigs and leaves and scraped bark from the infamous “gallows trees”. Seven lynchers were tried in court, but there were no convictions. The City could not afford to host another riot.

In tragic irony, 1934 was the first year that Nazis imprisoned Jews in concentration camps; Hitler used the images of the San Jose lynching in his despicable propaganda to show that ‘lawless mobs in California protected the Jews’. The ‘frontier justice’ lynching made international headlines and heated up telegraph wires. Lynching was not rare per se; public hangings victimized Blacks and Whites in the post-Civil War South, but there were near equal numbers of Whites lynched in New York, Pennsylvania and Colorado. In The West during the Gold Rush, White cattle rustlers and horse thieves were hanged as were Chinese in California and Mexicans in Texas— and in late 19th century New Orleans, 20 Italians were lynched.

Historians tell that lynchings happen mostly late at night and during colder winter months when crops are dormant, no agriculture revenue is coming in and money is scarce—in short, economic strife adds frustration and with no ethical qualms; mobs victimize the defenseless. Their awful unlawful actions may be defined by poverty, uncontrolled hate and volcanic anger as depicted in numerous films, including four about the San Jose incident; Fury, 1936; The Sound of Fury, 1950; Night Without Justice, 2004; Valley of Heart’s Delight, 2006.

Alex Hart, Brook’s younger brother, was 13 at the time of the kidnapping and was sent to San Rafael Military School and Santa Clara University, and then pursued a music career writing scores for Paramount Pictures. When his father died in 1943, Alex returned to head Hart’s Department store—switching from music composer to haberdasher. When I moved from Italy to San Jose, we shopped at Hart’s for shower gifts and children’s clothes and Alex often walked across the store just to say hello. We both supported St Elizabeth’s Day Home and he attended meetings. After Hart’s closed, Alex headed the I. Magnin fine jewelry department at Valley Fair where my mother-in-law, Marie worked in cosmetics. “The family sponsored San Jose’s first traffic light at Market and Santa Clara Streets, so customers could safely cross the street…” Marie told me.

It was the way things were in San Jose, nestled among blossoming orchards, The Valley of Heart’s Delight— before it burgeoned to The Valley of Silicon—times when people made phone calls, wrote letters, and chatted about family and unimportant things. Alex Hart was one of those Garden City people; always caring with elegant humility. Fame had come uninvited to the Hart family, and fame had come with great heartache—may I bid farewell to Mr. Panache, farewell to a forgotten era.