Anthony Bourdain (original) (raw)

BROWN DOG

You may be the most cynical, born and bred, citified lefty like me — instinctively skeptical of big concepts like “patriotism”, relatively foreign to hunting culture, unused to wide open spaces, but spend any length of time traveling around Montana and you will understand what all that “purple mountains majesty” is all about, you’ll soon be wrapping yourself in the flag and yelling, “America, fuck yeah!” with an absolute and non-ironic sincerity that will take you by surprise. You will understand why and what people fought and died for — or at least perceived themselves to be fighting and dying for when, either defending Native American hunting grounds against Custer, or “defending America” against foreign aggressors — and you will be stunned, stunned and silenced by the breathtaking, magnificent beauty of Montana’s wide open spaces.

Even in Butte, a place as scarred, poisoned and denuded by rapacious capitalist excesses as a place could be, you will see things, beautiful, noble even — a testament to generations of hard work, innovation and the aspirations of generations of people from all over the world who traveled to Montana to tunnel deep into the earth in search of gold and then copper, a better life for themselves and their families. Even the hard men, the copper barons who sent them down into the ground, you will find yourself begrudgingly admiring their determination, their outsized dreams, their unwavering belief in themselves and the earths ability to provide limitless wealth.

And when you look up at the night skies over Montana, it’s hard not to think that we can’t be alone on this rock, that there isn’t something else out there or up there, in charge of this whole crazy ass enterprise.

Or at least, that’s what I was thinking, after a long day of pheasant hunting, perhaps a bit too much bourbon, and Joe Rogan demonstrating an Imanari choke from omoplata (he damn near cranked my head off). I flopped onto my back, stared up at the universe and thought, as I always do in Montana, “damn! I had no idea the sky was so big!”

We show you a lot of beautiful spaces and very nice people in this episode, but its beating heart, and the principal reason I’ve always come to Montana is Jim Harrison, the poet, author and great American-a hero of mine — and millions of others around the world.

Shortly after the filming of this episode, Jim passed away, only a few months after the death of his beloved wife of many years, Linda.

It is very likely that this is the last footage taken of him.

To the very end, ate like a champion, smoked like a chimney, lusted (at least in his heart) after nearly every woman he saw, drank wine in quantities that would be considered injudicious in a man half his age, and most importantly, got up and wrote each and every day — brilliant, incisive, thrilling sentences and verses that will live forever. He died, I am told, with pen in hand.

There were none like him while he lived. There will be none like him now that he’s gone. He was a hero to me, an inspiration, a man I was honored and grateful to have known and spent time with. And I am proud that we were able to capture his voice, his words, for you.

I leave you with a poem Jim wrote. We use it in the episode, but I want to reprint it here. It seems kind of perfect now that Jim’s finally slipped his chain.

BARKING

The moon comes up.

The moon goes down.

This is to inform you

that I didn’t die young.

Age swept past me

but I caught up.

Spring has begun here and each day

brings new birds up from Mexico.

Yesterday I got a call from the outside

world but I said no in thunder.

I was a dog on a short chain

and now there’s no chain.

Up in The Villa

Some shows start out with a simple premise–or a nebulous one.

This one, set in the Greek island of Naxos, was the first one filmed for this season ( episodes are frequently shown out of sequence). The idea going in was quite simple: I go to a really nice, laid back Greek island–one with an actual local culture, businesses and income streams outside of tourism–and slide gently into another year of making television whilst maintaining my sun tan from summer vacation.

What did I know about Naxos? What did I expect to find?

I will admit to have done little homework and having had few expectations. I knew that Greece as a nation was going through an awful, crippling financial crisis. I had asked for a villa where I might putter about and do some cooking as a base of operations. What would it be like, removed from the mainland? Naxos, I knew, (and had insisted) was very different from Mykonos. It was not a party island. It was a blank slate. So the narrow slices of life depicted on this episode are me learning right there along with you. There’s a lot of delicious food. The place is, as one would expect, gorgeous. But there are surprises–and indicators both hopeful and ominous.

Hope you enjoy.

THE CHORUS

I spend a lot of my life — maybe even most of my life these days — in hotels. And it can be a grim and dispiriting feeling, waking up, at first unsure of where you are, what language they’re speaking outside. The room looks much the same as other rooms. TV. Coffee maker on the desk. Complimentary fruit basket rotting on the table. The familiar suitcase.

All too often, particularly in America, I’ll walk to the window and draw back the curtains, looking to remind myself where I might be-and it doesn’t help at all. The featureless, anonymous skyline that greets me is much the same as the previous city’s and the city before that.

This is not a problem in Chicago.

You wake up in Chicago, pull back the curtain and you KNOW where you are. You could be nowhere else. You are in a big, brash, muscular, broad shouldered motherfuckin’ city. A metropolis, completely non-neurotic, ever-moving, big hearted but cold blooded machine with millions of moving parts — a beast that will, if disrespected or not taken seriously, roll over you without remorse.

It is, also, as I like to point out frequently, one of America’s last great NO BULLSHIT zones. Pomposity, pretentiousness, putting on airs of any kind, douchery and lack of a sense of humor will not get you far in Chicago. It is a trait shared with Glasgow — another city I love with a similar working class ethos and history.

But those looking for a “Chicago Show” on this week’s PARTS UNKNOWN will likely be disappointed. There are no Italian beef scenes, no hot dogs, no Chicago blues, and there sure as shit ain’t no deep dish pizza. We’ve done all those things — on those other shows. And we might well do them again someday.

I like Chicago. So, any excuse to come back, for me, is a good one. It’s not a “fair” show, it’s not comprehensive, it’s not the “best” of the city, or what you need to know or any of those things. If you’re gonna cry that I “missed” an iconic feature of Chicago life — or that there are better Italian restaurants than Topo Gigio, then you missed the point and can move right on over to Travel Channel where somebody is pretending to like deep dish pizza right now.

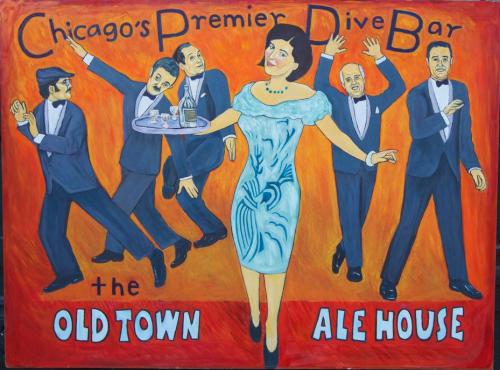

This is a show that grew out of my interest and affection for the Ale House in Chicago’s Old Town, and its proprietor, Bruce Cameron Elliot.

Ever since reading on the Twitter feed of the late great Roger Ebert that he read Bruce’s blog “ Geriatric Genius” every day, I have followed it faithfully. In fact, I went back years, tracking previous entries. It is in total, a breathtaking work, encompassing the daily lives (and deaths) and misadventures of the Ale House clientele — many of whom, I think it is fair to say, are heavy drinkers. Though cranky, occasionally pugilistic, opinionated, politically incorrect, sexually crude, and an awful speller, Bruce has, without judgement, chronicled the trajectories of a spellbinding array of characters. Whole lives pass, his characters rise and fall — and literally fall apart — as with one character, “Ruben 9 Toes”, who then went on to become “Ruben 8 Toes” then “4 Toes” before dying last year. Bruce’s closest associate, Street Jimmy is a crackhead who’s lived on the streets of Chicago ( no small feat) for over a decade — and his Greek chorus of bar regulars offer a perspective on Chicago that I thought deserved highlighting.

We visit with hip hop artist Lupe Fiasco and his extraordinary family, with chef Stephanie Izard, legendary producer Steve Albini and others — but the beating heart of this show is the Ale House and its resident artist (Bruce’s paintings of his customers, living and dead — as well as his portraits of politicians of both parties often depicted being penetrated inappropriately are world famous).

I urge you to visit his blog. And to go back and start a few years back.

There is something about the Ale House — its willingness to accept all who stagger in its doors (though there is, famously a NO SHOT list), it’s morbid sense of humor, it’s never ending flow of opinions, well formed and not, its willingness to scrap — that serves for me, as a happy metaphor for a city I love.

UNFINISHED BUSINESS

Tagalog, the language of the Philippines, is not an uncommon thing to hear in my household. Like many children all over the world, my daughter arrived home from the hospital to find a Filipino baby nurse. Vangie was with her from the very beginning of her life and in time my daughter came to know her son, her daughter-in law, their kids — and in time, an extended family and friends — in New Jersey, Southern California and the Bay Area — and of course, most importantly, Jacques, Vangie’s grandson, her best friend, from whom she has been inseparable since infancy — her older brother in every way but biological. Partners in crime. If I go back through old photos today, at least half will be of the two of them together. Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Years, vacations and birthdays, are celebrated together, our families in and out of each others’ homes interchangeably.

So, I have noticed some things, some features of Filipino daily life that I thought worth investigating. There’s always singing, for instance. Everybody seems to sing — an affinity passed on to my daughter. Family — and church, of course, loom large (even in my otherwise atheistic household). And food. My daughter is no stranger to sisig and sinigang and adobo and holds me in disregard for being unable to procure her the delicious Filipino pastries and breads she finds at her other family’s home. She knows a few phrases in Tagalog and looks at me pityingly when I don’t know what she’s talking about.

Nothing goes to waste around here. Anything, no matter how small, that could be of use to anyone who might need it back home, gets packed in a big box and sent to the other side of the world — if not to family members, to someone in need.

So, that’s what this episode is really about. It’s NOT about the Philippines. How could it be? There are over 7000 islands in the Philippine archipelago and I’m pretty sure I’ll die ignorant of most of them. It’s not even about Filipinos — as my experience, however intimate, is limited in the extreme.

And, as it turned out, our plans to explore beyond Manila were foiled by typhoon.

This episode is an attempt to address the question of why so many Filipinos are so damn caring. Why they care so much — for each others — for strangers. Because my experience is far from unusual. Hundreds of thousands — maybe millions of children have been raised by Filipino nannies. Usually mothers of their own children who they were forced to leave behind in the Philippines. Doctors, nurses, housekeepers, babysitters, in so many cases, people who you’d call “caregivers” but who, in every case I’ve ever heard of, actually care. Where does this kindness, this instinct for…charity come from?

For sure, to go abroad and look after others is a huge part of the Philippine economy. Overseas workers account for an enormous and vital part of the lives of those who remain. The government cannot be counted on to take care of its people — and Filipinos often have had to get really good at a do-it-yourself way of getting by, and hopefully, rising up. You see that attitude everywhere in Manila — in the makeshift Jeepneys that shuttle people to work and back, to the cobbled together homes in the poorer districts. Hammered together scrap wood but swept, kept clean, decorated with flowers or holiday decorations.

Not everyone in the Philippines, I should stress, has such limited options — but it is the overseas worker –and those they have had to leave behind, who interest me most this episode. I guess you could say it’s personal.

You will meet, in this episode, one woman — only one (and there are many, many like her) — who, in her 30 years abroad, separated from her children, raised DOZENS of people up, sent them to school, helped to improve their lives, built homes — before finally returning, her kids now middle aged. It is an astounding story — and not at all an unusual one.

There was one other bit of business I had to investigate.

For years now, in hotel bars in Chiang Mai, in lobbies in Singapore, cocktail lounges in Colombo and Kuala Lumpur and Hong Kong, wherever I go, I find a Filipino cover band able, on request, to play Dark Side of the Moon note for note — before moving on to Happy Birthday (in English, German or Cantonese), Patsy Cline, Celine Dion — and then Welcome to the Jungle.

I had to know more. Where do they all come from?

I hope the overseas Filipinos and our fans in the Philippines like this episode more than they liked the last one on our other show. This is certainly not the definitive show on the Philippines — and it will not be our last show there.

I imagine this time around there will be tears. At least I hope so.

We tried to do right by people who’ve been very, very good to us.

ISTANBUL

It’s a sprawling, beautiful city, still, in spite of the unrestrained construction where Europe and Asia meet. There’s no place like it — and for a time, until very recently, it looked like the future.

We arrived in Istanbul at a hopeful time. The election results were in and power was shifting away, it appeared, from Prime Minister Erdogan and his ruling AKP. So, our show is filled with cautiously hopeful people.

Subsequent events have failed to deliver on their optimism. Turkey is hardly the only nation I can think of where fear, xenophobia, and ethnic hatred are vote getters. There’s plenty of that around. More and more these days, particularly in times of uncertainty, people seem to look to a “man on a horse” to solve their problems — ANY man, it appears sometimes.

This week’s episode captures a particular moment in time in a beautiful yet troubled country, where it looked for a while, like anything was possible.

Now, I’m not so sure. But its a place well worth visiting, to see for yourself, to meet the people, to eat the (terrific) food, to take in the stunning architecture and scenery.

Don’t let my gloom and pessimism and general misanthropy stop you.

ETHIOPIA

Who are we and where do we come from? To what extent are we the sum of our parts? I wonder about stuff like that. And this week, my friend Marcus Samuelsson gets to ponder exactly those things as he and his wife Maya take me back to Ethiopia, to the towns they were born–and tell me their fascinating stories.

I’ve been meaning and hoping to visit Ethiopia and make a show there for years. But I would never consider doing it without Marcus coming along to put a personal spin on things. It’s always better, I think, when we can see a new or unfamiliar place through a specific set of eyes, to have a particular voice telling us about a place. Marcus, of course, is a very well known and respected chef with a number of businesses. I had to wait a few years for the schedules of two very busy people to align, but we got there in the end.

Ethiopia is a big, diverse place. Marcus and Maya come from two very different, distinct regions: different topography, different cuisine, different languages. They both left Ethiopia at different times in their lives and under very different circumstances. Maya has remained closed to her family and a more frequent visitor. Marcus has, only in the last few years, fully sought to investigate and engage family roots that were broken when he was an infant. So, watching the two of them experience Ethiopia in their own ways–and yet also, together, was fascinating.

I learned a lot about a beautiful country while making this episode, and enjoyed doing it. I hope you will too.

Great food, great music and some really deeply personal stories….

This Sunday night!

RYUKYU

I ate delicious Yakisoba. And fluffy egg salad sandwiches from my favorite convenience store. I watched old school karate close-up. Maybe too close. I found out I am not completely horrible at “tegumi”, a relatively fat-free version of sumo (though I won’t be making a career of it).

Okinawa is the largest island in the Ryukyu archipelago, a kingdom, a culture and a people until 1879, separate from Japan. You feel that difference immediately. It feels, relative to mainland Japan, like Southern California or Florida; balmy, tropical. Where the mainland feels frenetic, wired tight, neurotic, Okinawa is decidedly laid back.

They have, since World War II, endured the mixed blessing of a disproportionate number of US military bases, a proximity that has influenced the cuisine—the most famous (or notorious) example being Taco Rice—and have always been, like their Chinese neighbors, more pork-centric when it comes to protein of choice.

Laid back, yet with a strong and steady tradition of activism. Okinawa paid an awful price in the final months of the war, losing up to a quarter of their population. It was sacrifice many feel bitter about still—as Okinawans then—and now—feel as if they are treated as second class citizens by the central government.

Laid back but with a long and glorious tradition of martial arts. This, after all, is where karate comes from. Okinawa is where I found out that having a thumb crunched into the cartilage of the ear can really, really hurt. You will see an elderly karate master at one point effortlessly manipulate the digits of my hand. The fingers are messed up still. The “warm ups” at the dojo you will see in the show, by the way, are no joke. I sat there for 45 minutes and watched in horror as the students did things to their knuckles and toes and forearms that nature, I don’t think, ever intended. Absolutely brutal.

The end of the show, a woman karate practitioner is called over to the table to explain things. She ends up perfectly capturing the difference between Okinawa and the rest of Japan. It’s a beautiful moment.

BUDDY PIC

In the cinematic genre known as the “Buddy Pic”, custom and tradition demand that the two protagonists adhere to classic roles—as codified by Felix Unger and Oscar Madison in “The Odd Couple” and persisting through such bro-tastic tag teams as Nick Nolte and Eddie Murphy, Danny Glover and Mel Gibson, Robert DeNiro and Charles Grodin, and beyond. One character must be the “straight man”, the reasonable person, exasperated, perhaps, but relatable—and the other, the “zany” one: obsessive/compulsive (Unger), unpredictable (Murphy), neurotic (Grodin), manic depressive and suicidal (Gibson). The two unlikely heroes, thrown together by fate, must overcome their enormous differences so that they can, by working together, triumph over evil and by movie’s end, have a learning and growing moment.

I don’t know if I learned anything while running around Marseille with my good friend Eric Ripert. I knew already that I liked cheese. As it was the South of France we were shooting in, I had reasonable expectations that things would not suck.

Eric, though, definitely learned something. He learned that Marseille, France’s second largest city, is awesome. He didn’t know this because he had never been there before—which is kind of incredible—given that he grew up only a HUNDRED MILES AWAY in Antibes. It’s like someone who grew up in San Diego never having been to Los Angeles.

Why would that be?

How could that be?

Well, maybe it’s because the French don’t seem to want you to go to Marseille. When I told a French government official I met at a party that I was planning a trip to France for the show, his face lit up with interest, “Oh, fantastic! Where will you visit?” When I answered, “Marseille,” his expression sagged with disappointment. This reaction repeated itself a number of times as one Frenchman after another took an immediate attitude of befuddlement—even pique—when informed of my plans. Perhaps they assumed I would be focusing my attention on Marseille’s rich and lurid history of organized crime activity—as seen in such films as “The French Connection” and its sequel. Those days are largely past and that was not what I was interested in. A fair number of French will tell you in unguarded moments, that “Marseille is not France”, and what they mean by that is that it’s too Arab, too Italian, too Corsican—too mixed up with foreignness to be truly and adequately French. But anybody who knows me knows that’s exactly the kind of mixed up gene pool I like to swim in and eat in. It is a glorious stew of a city, smelling of Middle Eastern spices and garlic and saffron, and the sea.

So in this episode, I got to introduce Eric to part of his own damn country—his own neighborhood—for the first time. So which one of us is the crazy one? Me? Or the man who in all his life never visited his nation’s second largest metropolis—even though it was just down the road?

While we agree on the important things: food for one, we are very different people. Eric is a Buddhist. As long as I’ve known him, I’ve never seen him wish ill on anybody, whereas I regularly fantasize about planting my enemies in shallow graves. As the chef and an owner of three Michelin star Le Bernardin, he has a reputation to protect. I do not. As many of the world’s wealthiest, most powerful and influential people are regular customers of his, Eric must be constrained at all times in his opinions. He’s a diplomat. I, on the other hand, have pretty much made a living of insulting people. Eric speaks English, French and Italian fluently and has never cooked anywhere but the best kitchens in the world. I speak English, kind of. Though both parents were fluent my French is pretty awful—though it improves when I’m drunk—and my Spanish is suitable only for insulting people. I spent much of my career cooking brunch.

It can be a difficult thing to be my friend given some of my previous behaviors, my free and perhaps too-frank giving of opinions. I’m sure it’s caused Eric awkwardness at times. Which is why it’s so much fun to torture the guy.

Ask him what he thinks of some horrible despot who dines regularly at Le Bernardin and watch him squirm. “He has very good taste in wine”, would probably be his answer. So, I enjoy my tiny victories: Forcing him to make pizza in the back of a food truck would be one of them. (Pizza is very big in Marseille).

Maybe there was some “learning” at the end of this particularly buddy pic after all. We both learned that Marseille is a great under-appreciated travel destination, a hidden gem that isn’t hidden at all. It’s right there in plain sight. A great city with great food, great views, sitting right on the edge of the blue Mediterranean, surrounded by freakin’ PROVENCE. It’s got it all.

And we learned that Eric’s pizza making skills are for shit.

CUBA!!!!

The toothpaste is out of the tube and there’s no putting it back.

Cuba is changing. It’s changed dramatically already, just in the few years since I was last there—and those changes are accelerating at a rate that no one can contain or control.

It’s long overdue.

It’s ludicrous that ordinary Cubans, 100 miles from our shores, have been excluded from the international conversation, deprived for so long of basic internet access, social media, even the ability to watch American baseball on TV.

All that will change.

It’s a country on the verge of something. I think it’s a country on the verge, among other things, of a tourism boom beyond anyone’s imagining. Because whatever your feelings on the Cuban government of the last half century, Cuba itself is beautiful. The Cuban people are uniquely wonderful: proud, resourceful (you sort of HAVE to be in Cuba), educated—and funny as hell. Even crumbling from neglect, Havana is the most beautiful city in all of Latin America or the Caribbean. The rum is the finest in the world, bar none. The music fantastic.

Everyone in the world will want to go there—and they soon will. This episode of PARTS UNKNOWN, the first of the season, marks a return. And I think you will be very surprised at what you see. I know I was.

Please take note of the tail end of the episode. A long tracking shot of people, mostly young Cubans hanging out by the Malecon in Havana. We have sort of a bet among ourselves—those of us who make the show— where we challenge each other to see how long we can hold a sequence without voice over, or dialogue. Just allow the images to speak for themselves. I think we outdid ourselves this time. I’m very proud of it.

BACK TO BEIRUT

I briefly considered naming my daughter “Beirut”. She was, after all, conceived within two hours of returning from my first visit there. In 2006, along with my crew, and a number of other foreign nationals, I had been taken off the beach by the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit and transported by LCU to the USS Nashville, and from there to Cyprus and home.

The experience left me with a deep love and appreciation for the US Navy and Marines, the now decommissioned Nashville (once referred to affectionately, I’m told, as the “Trashville”), and, of course, Beirut.

That experience changed everything for me. One day I was making television about eating and drinking, the next, I was watching the airport I’d just landed in a few days earlier, being blown up across the water from my hotel window.

I came away from the experience deeply embittered, confused—and determined to make television differently than I’d done before. I didn’t know how I was going to do it—or whether my then network was going to allow me—but the days of “happy horseshit”, the uplifting sum-up at the end of every show, the reflex inclusion of a food scene in every act, that ended right there.

The world was bigger than that. The stories more confusing, more complex, less satisfying in their resolutions. As I noted in my utterly depressing last lines of Voice Over in the eventual show we put together: in the real world, good people and bad alike are often crushed under the same terrible wheel.

I didn’t feel an urge to turn into Dan Rather. Our Beirut experience did not give me delusions of being a journalist. I just saw that there were realities beyond what was on my plate—and those realities almost inevitably informed what was—or was not—for dinner. To ignore them now seemed monstrous.

And yet, I’d already fallen in love with Beirut. We all had. Everyone on my crew. As soon as we’d landed, headed into town, there was a reaction I can only describe as pheromonic: the place just smelled good. Like a place we were going to love.

You learn to trust these kinds of feelings after years on the road.

We soon met lovely people from every kind of background. We found fantastic food everywhere. A city with a proud, almost frenetic party and nightclub culture. A place where bikinis and hijabs appeared to coexist seamlessly—where all the evils, all the problems of the world could be easily found—right next to—and among all the best things about being human and being alive.

This was a city where nothing made any damn sense at all—in the best possible way. A country with no president for over a year—ruled by a power sharing coalition of oligarchs and Hezbollah, neighbor problems as serious as anyone could have, history so awful and tragic that one would assume the various factions would be at each others throats for the next century—yet you can go to a seaside fish restaurant and see people happily eating with their families and smoking shisha, who, in any other place would be shooting at each other.

It’s a beautiful city, with layers of scars the locals have ceased to even notice. It’s a place with tremendous heart. It’s a place I’ve described as the Rumsfeldian Dream of what, best case scenario, the neo-con masterminds who thought up Iraq, imagined for the post-Saddam Middle East: a place Americans could wander safely, order KFC, shop at the Gap. Where dollars are accepted everywhere and nearly everybody speaks English.

That is an egregious oversimplification. But it’s also my way of telling you should go there. It defies logic. It defies expectations. It is amazing.

EVERYONE should visit.

CALL ME ISHMAEL

I have, in my 14 years of traveling the world in search of kicks, seen many things. But I want to tell you that my experience during the closing sequence of this episode of PARTS UNKNOWN was, short of watching the birth of my daughter, the most amazing. I hope your TV set is big enough to convey the sense of being where I was, and having something that….large…coming up at you from the depths. I suspect you’d need an IMAX. Absolutely breathtaking.

Those of us who were not born in Hawaii, who do not live there, can be forgiven, I hope, for imagining it a paradise. It has been sold as such to many a generation of white guys of a certain age: warm, “exotic”, festooned with palm trees both real and on shirts, populated (the brochures would have you believe) by friendly musicians, brimming with the spirit of aloha—and dusky skinned women who dance a lot.

As patiently, as often or as stridently as actual Hawaiians might might want to disabuse us of these notions, pointing out that unemployment on the islands is brutal, that young Hawaiians are finding it nearly impossible to find affordable housing in the communities they were born, that traffic gets worse every year, we have a hard time seeing anything but gin clear water, green mountains and the kind of place we’d like to die: drifting off in a hammock perhaps, the sound of ukuleles in the distance, the only immediate sign of death the shaker glass full of Mai Tai that falls from our liver spotted hand.

And it is those things, surely: a place where a gentleman such as myself might spend the rest of his years, padding about in a sarong, smoking extravagantly good weed, eating pig in many delicious, delicious forms. But Hawaii is actually much, much cooler than we know. MUCH cooler. It’s both the most American place left in America (in the best and worse senses of that word) and the least American place (in only the best sense). It’s Main Street America in so many ways—socially conservative, family oriented, fairly straight laced in its appetites, suspicious of outsiders, and shot through with all the usual suspects of American business you’d want and need and expect from Wasilla to Waco to St. Paul.

And it’s also, deliriously, deliciously, not American at all: its spine, its DNA, its soul, the descendants of warrior watermen—the original people who navigated their way across the Pacific and settled the islands– and Okinawans, mainland Japanese. Chinese, Filipinos, Vietnamese—a glorious stew similar to some of my other favorite deep gene pools, Singapore and Malaysia, where two people meeting at a party, have to inquire each others’ parents were—and where they might have come from to untangle the question of exactly who’s who. Everybody too mixed up to hate anybody in particular. This fits in nicely to my probably naive theory that we can all bone our way to world peace eventually, but thats another matter.

Point is: how can you not love a place that embraces Taco Rice? What a journey that dish has made: a fake Mexican dish created by Okinawans for homesick non-Mexican American GI’s, eventually embraced by the Japanese, the spoor then migrating back to America, to be embraced anew. Or SPAM musubi? Does mutated, cargo cult cuisine get any better? SPAM noodles? Chicken katsu with potato macaroni salad? Every great culture, eventually, throws a pig or other large animal into a hole in the ground—and the Hawaiian version is, unsurprisingly, particularly delicious, but it’s the beef patty with shiny gravy, the mash ups of Japanese and American diner, Filipino and Vietnamese that make me happiest. The food, at every level, from casual to fine dining, by fully exploiting the awesomeness of that cultural mix, gets better and better and better every year.

The placewhere I was happiest in Hawaii was the place everybody (native Hawaiians included) insisted that I would probably be least happy—or least welcome: Moloka’i. Those proud, tough, obstinate, mother****ers (and I mean that in the most admiring sense I could possibly use that word) are exactly the kind of people we need to save us all from the worst of “progress”. We need people like that in post-Bloomberg New York. Bubba Gump and The FieriDome would have never dared to soil my beloved city—and Donald Trump would be regularly punched in the face. In short, paradise.

I was treated with enormous kindness and generosity everywhere I went—nowhere more so than Moloka’i. My ignorance and naive preconceptions tolerated with patience and good grace. This is one haole who feels very, very honored and grateful for the many kindnesses shown me.

A special thanks to the man, the legend, Shep Gordon, talent manager extraordinaire, the man who can, it can be credibly maintained, single handedly moved chefs from their powerless huddle in the back stairs service entrance, to the big stage—and changed the world many times over. He was my host with the absolute most in Maui. If you have not seen Mike Myers’ film about Shep’s outrageously extraordinary life, SUPERMENSCH , you should do so immediately.

VISIONS OF LIGHT

If you’ve been following the show for any period of time, you’ve probably picked up on the fact that I’m a hopeless cinematography geek. That everybody who works on the show is a cinematography geek, that we’re the type of people who, in their spare time, sit around talking about directors of photography we love, films whose looks we are inspired by, and whenever possible emulate (if not outright rip off). It’s expected of the people who work with me. If you don’t know who Gregg Toland is—or Vittorio Storaro or Chris Doyle, chances are you’re not going to make it on the PARTS UNKNOWN road crew. That’s the kind of nerdy, dysfunctional, annoying people we really are.

So, all of us were super-geeked about the gentleman who agreed to take us back to Hungary, the country of his birth, and walk us through some of the locations that figured heavily in the past. His name is Vilmos Zsigmond, and he is the cinematographer responsible for some of the most strikingly beautiful, iconic images in the history of film. His work on Robert Altman’s McCABE AND MRS MILLER changed the craft forever. He also shot such films as THE DEER HUNTER, DELIVERANCE, CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, THE LONG GOODBYE, and many, many others.

In 1956, he was fresh out of film school when the Hungarian people rose up, and to everyone’s amazement, seemed to sweep their Soviet occupiers right out of their country. For a few short days, it seemed too good to be true. And it was. The Soviets returned in force, rolling tank columns into Budapest and brutally crushing any resistance. With a camera “liberated” from their film school, young Vilmos and his close friend and fellow film student, Laszlo Kovacs (later to also become a legendary cinematographer), at great peril, filmed all of it. They took to the streets and shot everything they could. The uprising, the street fighting, reprisals against the despised secret police—and the overwhelming response by the Soviets. With the film cans under their arms, determined to show the world what had happened, they snuck across the border into Austria—and began the long journey that ended up, strangely enough, in Hollywood.

So we are taking a very unique, very personal look at what is, without question, one of Europe’s most stunningly beautiful cities. I was kicking myself throughout the shoot at the fact that I hadn’t been there earlier. If you are into architecture porn, Budapest is for you. One incredible building after another. Block after block of what is simply an incredible mix of styles, the imaginations of the creators gone wild during the city’s years of empire. It is really something to see. And I felt like a total rube arriving so late. What took me so long!?

It is also, apparently, the foie gras capital of Europe, so there’s just no excuse for not having come sooner. The food is delicious. The people lovely. The scenery unlike anywhere else on earth.

I can tell you for sure that our camera guys have never been so excited—or intimidated by a subject. Vilmos may have been only the subject and guide, not the director of photography, but he was always watching. I like to think that his presence—and the magnificence of the location, inspired all of us to do our very best.

A disproportionate number of our greatest photographers and cinematographers seem to have come from Hungary. Noticing that, we reached out to Vilmos—who was kind enough to give us his time, share his life story, walk us through some of it. Having now been to Budapest and seen how incredibly, uniquely beautiful it is, I can well understand how so many visual stylists came from there. It was inevitable.

HIS DREAMS WALK ABOUT THE CITY WHERE HE PERSISTS INCOGNITO

I woke up this morning in Borneo, went for breakfast in a crowded kopi tiam, where I greedily devoured a lip burning, nose running, utterly delicious bowl of Kuching style laksa. Tomorrow, I’ll board a long boat and, for the second time in my life, head up the Skrang River—this time for Gowai, the Iban harvest festival, where I will, I am warned, be drinking way too much rice whiskey. I have asked that my former headhunter hosts give me a hand tap tattoo. Possibly a durian pattern. I have been having regular foot massages—something they do particularly well in this part of the world. My room smells of jasmine, and outside the window, across the river, the former palace of the “White Rajah” of Borneo is visible in the late afternoon light. The muezzin’s calls to prayer will soon echo from the mosques throughout the city, one voice joining another, then another—a chorus from every direction.

And yet….and yet…in the midst of all this….exotica…my mind runs to New Jersey.

New Jersey, too, was exotic to me, once. For much of my childhood. The then working class riviera of Barnegat Light where I spent many happy summers. The dark mysteries of off season, pre-casino Atlantic City, with its vast, empty hotels, its novelty shops, boardwalk, salt water taffy and amusement pier. Leafy bedroom communities where I grew up, others where I was later whisked off to school…the hard packed night time slopes of Great Gorge and Vernon Valley…the fabled Pine Barrens, where untold horrors awaited amidst the discarded gangsters and mythical, griffon-like creatures said to feast on little boys. The fastidious, house proud Victorian severity of Ocean Grove right next to the decidedly honky tonk Asbury Park. The Palisades. The meadowlands—a vast wonderland for juvenile delinquents…Even the refineries of Elizabeth had secrets—their omnipresent but ever changing odors, unknowable. I came of age as a passenger in cars driving aimlessly around Route 80, Route 46, Route 4 …cruising for burgers, cruising for girls, cruising just…because….

So, to me, much maligned New Jersey was always magic. Until, like so many of us raised in the Garden State, I left—forever—for better, more “sophisticated” territory. In my case, right across the river to New York City. Everybody, of course, is from New Jersey: Frank Sinatra, Jack Nicholsen, Meryl Streep, William Carlos Williams, Alan Ginsberg, Queen Latifah, Stephen Crane, Glenn Danzig, Peter Dinklage, Donald Fagen, Ray Liotta, Martha Stewart, Lee Van Cleef, Tom Colicchio and..oh yeah…Bruce Springsteen. Anyone else not listed here was probably born there but just won’t admit it.

I get angry now when people speak badly of my home state. (I may not have been born there—but I was certainly raised there from infancy until age 17). And I get angry, from afar, when people abuse it, try to paint it in a bad light. Certainly the reality series, depicting roid-raging, Valtrex popping mesomorphs did the state no favors. But New Jersey hardly has the exclusive on meatheads.

I’ve watched in dismay for much of my life as politicians from both Democratic and Republican parties have used New Jersey as their personal feeding trough. And if you think the Christie traffic scandal was no big deal, think about how you’d feel if it was YOUR 6 year old daughter, first day of school, trapped in a school bus for 4 hours, desperate to not piss herself in front of her classmates—all because a bunch of vindictive, spiteful, gloating political hacks were peeved about matters completely outside your control or understanding—and decided to use YOUR kid as a club to beat their perceived enemy with. YOUR dad, waiting for an ambulance or emergency responder.

And certainly, what’s become of Camden, once a principle engine of the industrial revolution, after generations of mismanagement from the other political party is even more egregious. And has anyone, ever, taken as large, as ugly, as steaming a shit on a city as Donald Trump’s ‘Taj Mahal” in Atlantic City? LOOK at it! (We do, in this episode). Can you imagine an uglier, tackier structure—one more oblivious to its surroundings? It seems designed specifically to obscure the beach, the boardwalk, the gorgeous architecture of Atlantic City—the very things that (still) make AC wonderful. Of course, Donald seems eager to separate himself from his leavings these days—not because it’s an architectural abomination—but because it’s apparently become a financial embarrassment.

It would be easy to make New Jersey look amazing if I concentrated on its farmland, its beaches, its parks and its finer restaurants. Easier still if we chose to film in summer. But I thought, let’s shoot this show in WINTER. When New Jersey is supposedly at its greyest, most inhospitable, ugliest. And lets go right to those parts of New Jersey that are supposedly the most fucked up, the places where everything went horribly wrong. It is MY contention that New Jersey is so magnificent, so unique, its spirit so unsinkable and its sense of humor unparalleled that even there, seeing those places—as I do—with affection and respect and no small measure of hope, that those who watch this episode will find my beloved home state awesome and beautiful too. Even the refineries—the sprawl of bridges and highways and clover leafs—there’s beauty there. We worked mightily to show you those things as we saw them. As I feel about them.

New Jersey, it is my contention, was amazing all along. It was when we tried to “fix it” that we went astray. Drive Ventnor Avenue from Atlantic City to Margate and look out the window, and you’ll see, still there in parts—what was lost and what could be again. Look at Asbury Park—how its coming back—against all odds. And watch one lone woman’s struggle in Camden to take back, one block and one child at a time, a city she grew up in, loves fiercely and wont let go of.

The hero sandwich of my youth. Steamer clams. Jersey Italian. Birch beer. The smell of dune grass. Vanilla salt water taffy. Fried clam strips. These things should be eternal. They are eternal.

THAT QUEASIFYING MOMENT

Travel is not always comfortable, even when the scenery is at its most beautiful. You look out the window, or you get too close, and the reality of the situation—the world you will soon be leaving behind—intrudes. I’m talking, of course, about crushing poverty, hunger, the kind of desperation people can find themselves in when feeding themselves and their families becomes a matter of immediate urgency. On Parts Unknown, we travel to a lot of places where people are poor. We either choose—or don’t choose—in every case, to concentrate on that aspect of daily life. We try—we try hard to acknowledge the reality of the situation, but often, admittedly, we shy away from diving too deep into awfulness because we’re aware that viewers will often be unable to take it, that they’ll find prolonged depictions of the way millions of people live around the world just too damned depressing. They will, in all likelihood, change the channel. And we don’t want that.

So we make choices all the time. Choices about what I will show you of what I saw and experienced during my limited time in a destination—and what I won’t. It’s my show. I decide where we go. I decide what we do when we get there. And I decide what we show you when we get back and edit down 60-80 hours of footage to 42 minutes. That is a manipulative process. And not, inherently anyway, a bad one. I want you, the viewer, to feel the way about a place the way I want you to feel. I want you to look at it and see it from my point of view, if at all possible. Or at least, consider other points of view. But it is, almost always just one point of view —or one lens through which you are seeing things: Mine.

Not this week.

This week on Parts Unknown, we go to the little understood island nation of Madagascar—and we go with someone who most definitely has his own point of view. Darren Aronofsky is the acclaimed director of the films Requiem For A Dream, Pi, The Black Swan, The Wrestler and Noah. People often ask what it would be like to come along on a shoot with me. Now you will see. We look at Madagascar, in many ways, through Darren’s fresh set of eyes. It’s a useful reminder, worth having, that what you see on the show is not the only angle. That we are looking at the world out my window. That there are other windows. That maybe, I’ve omitted something, shaded something, if only to present myself in a more flattering light.

I was thrilled and honored and delighted when Darren approached us about coming along somewhere in the world to play with me and the Parts Unknown crew. It was his idea to go to Madagascar, largely for its unique eco-system and its environmental situation. My only request was that he shoot some footage—with whatever device he wanted to use. And that, at some point, he give us his version of at least a portion of the show for which we have already seen my version. So in ACT SIX, you will get an example of what may or may not be missing from the shows we make. An ugly, uncomfortable reminder that its not just pretty pictures and neat, hopeful sum-ups. It does not, I’m pretty sure, portray me in the best light. Or any of us for that matter. But there it is. I thought it was important.

I want to take this opportunity to thank Darren for being a great travel companion. Nearly two weeks of at times, very difficult living. Long, long uncomfortable train rides, bugs, hard beds, minimal plumbing, terrible heat. Darren is a vegetarian, so eating must have been tough. Though he seemed to be getting by mostly on rice, he never complained. Though he is in preproduction on a major Hollywood film, I never saw him on a cell phone. He never complained about lack of internet—or anything else. He went fully off the grid for the length of the shoot and appeared to enjoy himself the whole time. It’s a sobering reminder—one of many this episode—of how lucky I am.

C***

These days, most mornings, wherever I am, I wake up early and go train in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. If at home in New York, I’ll prepare and pack lunch for my daughter, walk her to school, and shortly after, be on my way to Renzo Gracie Academy where I will spend the better part of the next hours trying to prevent someone half my age from choking me to the point of unconsciousness. Often, I will look over from under a haze of sweat and exertion, to see my wife practicing the dark arts of knee reaping and heel hooking with her instructor or training partners. Sometimes, at risk of being arm-barred, I will wave. If abroad or on location, I’ll take what I can get. I’ll train wherever I can, wherever they do jiu jitsu: a strip mall in Maui, a cellar in Budapest, a military base in Okinawa—a cold storage facility in Glasgow. Standards of behavior and the physical condition and skill levels of my fellow practitioners vary widely from place to place. Face cranking and “can opening”, frowned upon in most academies, is apparently just fine (and done with a smile) in Hungary. Competition can be tough, it turns out, on Okinawan military bases—when you’ve spent most of your training learning to hunt and constrict exposed necks—and most of your jarhead rolling partners no longer have them. In Hawaii, they tend to have rather large torsos, so finding yourself in side control is particularly unpleasant. I have had my ass kicked in many lands—but it was particularly tough in Glasgow. This should not, in retrospect, have been a surprise. Glasgow is famously, a tough town. Notorious for its hard drinking, hard living, hard ass citizenry—and its uniquely merciless sense of humor. I fell in love with Glasgow immediately on my first visit. I was barely off the train and within minutes was called a “c**t”. Though pretty much the worst thing you can call anybody in America, here, in Glasgow, I found, it was in a casual expression of affectionate—useful in nearly every social situation. “Oi! You’re the c**t who wrote that cookery book! Loved that book! Have a pint!” I have since learned to love the customs and practices and oral traditions of the Glaswegian—even when I can’t make out what the hell they’re saying. Which is, admittedly, much of the time. It’s Europe’s No Bullshit Zone. Nobody takes themselves too seriously. Most of the time when I get my ass handed to me, it’s a much younger, fitter, or higher ranked practitioner—often with high school or college wrestling experience. So, in Glasgow, I figured, looking at the shorter, less physically imposing old dude I’d be rolling with, that I had this. I was a foot taller. He was close to my age. I thought; “once Pops gets a taste of my Shoulder of Justice on his neck, it’s gonna be tap, snap, or nap.” I could not have been more wrong. It was like running into a fire hydrant. He crushed my rib cage in his guard like a box of year old Triscuits. His fingers were socket wrenches, his chest an engine block, his arms and legs apparently manufactured from some kind of cable—the stuff they hang suspension bridges from. Everything he did hurt. I ended up pounded into the mat again and again, grateful when the murderous (yet relentlessly cheerful) garden gnome would finally grab hold of an arm or neck so I could tap out gratefully.

Scottish jiu jitsu is tough. But stalking deer in the Scottish Highland is the hardest, most physically demanding single activity I’ve ever done on camera. It doesn't look like much. A nice walk up some hills, across the moors, in traditional Scottish kit, carrying nothing more cumbersome than a walking stick. You don’t even have to carry your rifle. The gamekeeper does that for you. The hills and peaks, the mountains of the Highlands are incredibly beautiful—the footing alternately firm and hard against flinty rock and hard packed soil—then soft and spongy among the heather and scrub of the moors, then steep, near vertical inclines. The idea is to walk up, at a reasonable pace, higher and higher, the incline gradual, legs fine, then not so fine, then burning with exertion. After a few miles, by which time, you’re congratulating yourself on having made it so far, the gamekeeper might spot a suitable animal through his binoculars—about a mile away. “If we sneak around the back that way—behind that mountain—and make our way quietly across that ridge—pop out over there-” he suggests, pointing at a harrowingly steep range of what sure as hell look like mountains to me, “we might just surprise him.” This is yet another climb requiring some skill and no small amount of exertion—and at least another hour—all in the cause of sneaking up on an animal who, more than likely will be gone by the time we arrive at our position. We spend a lot of time crawling through wet heather and brush. It’s raining in that kind of omnipresent, thin drizzle kind of way—almost a mist that the French used to call “Le Crachin”. Which is to say, by the time I finally manage to successfully shoot an old stag in the brain, I am pretty happy at the prospect of walking downhill for a change. But, no. Downhill, it turns out, is worse. MUCH worse. A couple of miles of relentless incline and my knees, deprived of the kind of shock-absorbent cushioning of my younger years, are in full rebellion. I’m hobbling like Long John Silver, making little grunting sounds with the impact of each step, trying, somehow to take it sideways all the way home.

But the countryside I was dragging my bones across was some of the most savagely beautiful on earth. I had successfully, and neatly, with a minimum of force, shot a stag. There would be venison and Scottish game birds at the lodge for dinner. A roaring fire in every hearth, and a spirited game of snooker no doubt. Much fine whiskey—not uncommon to the region, it turns out, would be enjoyed—and fine Scottish cheeses. As the logs burned down to embers and my glass refilled yet again, I would be permitted, for a few, golden moments, to feel like a country gentleman, a deer stalker, squire of the moors…and definitely not a c**t.