History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy (original) (raw)

Troubled Parents

The Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company, Limited, was promoted in April 1864 to manufacture and lay underwater cables. It was a stunningly successful concern that constructed something like ninety per cent of the world’s submarine communications in the next fifty years. It was a major industrial enterprise that integrated its production from the plantations of the Far East, to iron works and resin works, through to commissioning and operating its own fleet of cable-laying ships. From its creation it was powerful enough to lend its own credit to support the many operating companies that were formed to finance and work intercontinental, ocean and short-sea telegraph lines.

As is well-known, TCM was formed by the merger of two private companies, Glass, Elliot & Company and the Gutta-Percha Company, into a limited-liability joint-stock or public company, drawing its capital from a mass of small investors rather than from a handful of individual proprietors.

The history of the two parents that were to comprise TCM is clouded by partial memories of their contemporary historians. Distinct from those the following account is drawn mainly from the law reports of the time relating to the many actions that the two suitors to the eventual marriage engaged in which give an unvarnished description of their evolution.

But before proceeding with the parties to the marriage we must first, against all logic, deal with the fruit of the union...

The progeny

Glass, Elliot & Company and the Gutta Percha Company together produced submarine cables for electric telegraphy. The former also made iron wire and the latter a mass of resin products and electrical cables for underground use.

For the uninitiated at its most simple a submarine telegraph cable consists of two primary elements; the insulated core and the external protective armour. Secondary elements include packing between the core and armour and anti-corrosive protection to the exterior. Insulation of cables was of natural resin, either india-rubber or gutta percha. These were soft materials, subject to abrasion and attack by sea creatures. To give long-term durability submarine cables were additionally covered with closely-wound iron wire, a process similar to the manufacture of iron wire rope.

Typical submarine cable of the early 1850s

The earliest subterranean cables, widely used in England, Germany and Russia for a short period in the 1850s, as an alternative to vulnerable cross-country wires strung from wooden posts, had the resin-insulated copper core covered with strong cotton-web and a sanded bitumen outer coating.

Why gutta percha and not india-rubber? Although superficially similar it was soon discovered that india-rubber and gutta percha had differing properties. Essentially, india-rubber was found, after treatment, to be durable when exposed to air; gutta percha to be extremely long-lasting when immersed in water. India-rubber suffered from exposure to heat and gutta-percha became brittle in air. For many years only gutta percha could be extruded to cover wire; india-rubber could not and had to be spirally-wound around the metal core. Several cables were to be successfully insulated with india-rubber but not until TCM was established.

The party of the first part

The origin of the firm of Glass, Elliot & Company dates from the year 1842, at which time the partnership of Heimann & Küper, manufacturers of patent iron wire rope, was created in London. The original participants were Johann Baptiste Wilhelm Heimann and Johann Georg Wilhelm Küper. Heimann, recorded as a ‘merchant’ of Ludgate Hill, London, was granted an English patent for improvements in the manufacture of ropes and cables on March 8, 1841 and the partnership was formed to work that patent. It likely that Heimann, as a ‘merchant’, was acting as agent for another German as Wilhelm August Julius Albert of the mining town of Clausthal in the Harz mountains had perfected iron wire rope between 1831 and 1834 some years prior to its introduction into Britain. Unfortunately for history, until 1853 patents in England did not have to record the originator of patents communicated from abroad.

Heimann & Küper soon established a wire-rope-making works on the Grand Surrey Canal at Camberwell in south London.

All interested in underwater telegraphy will be aware that the firm of R S Newall & Company of Gateshead, Northumberland, manufactured the first successful iron wire armouring for submarine cables in 1851. Robert Samuel Newall made extravagant claims as to the invention of iron wire rope and to submarine telegraphy in general. His original patent for iron wire rope dated from August 7, 1840. Based on the undoubted success of the Channel cable his firm subsequently attempted a monopoly in making submarine cables.

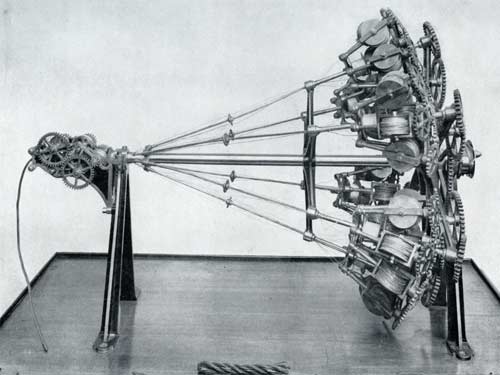

Model of R.S. Newall's original compound wire-rope making machine

However there were other patentees of iron wire rope: the earliest and most notable being Andrew Smith, of 2 White Lion Court, Cornhill, London, whose patent dated from January 1835, with three successive improvements to 1839. As background it might be explained that the manufacture of wire rope was accomplished by winding spirals of iron wire around a core of hemp rope. Subsequent patents by Smith, Newall and Heimann improved the machinery for winding the spiral and the form and size of the individual wires.

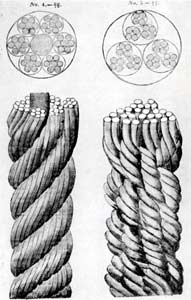

Andrew Smith's patent wire rope. Mining Journal XIV, Dec 7th, 1844

Smith was eventually to be the main provider of iron wire rope rigging for the sailing ships of the Royal Navy from his works at Millwall, Poplar. As well as iron wire rope Smith made copper wire rope for use as a lightning conductor, and produced the first steel wire rope in 1840. He also granted many licenses to other manufacturers. Newall repeatedly tried to challenge Smith’s patents, especially when Smith’s licensees constructed the earliest but unsuccessful cross-Channel submarine cable. The court of the Queen’s Bench found in 1851 that the differences in Smith’s and Newall’s cables were scarcely distinguishable and although finding in Newall’s favour awarded him just one shilling in damages. In another case against a Smith licensee the Exchequer Court awarded Newall forty shillings...

Smith did not enter the submarine cable business himself but several of his licensees did until prevented by Newall’s actions in law.

Even before this aggravation, Smith’s vigorous competition had driven the partnership of Heimann & Küper to insolvency in November 1848. The firm was fortunate to acquire new investment through additional partners in the form of George Elliot and Richard Atwood Glass. Elliot was a wealthy coal-owner from Gateshead, near Newcastle upon Tyne, and was sufficiently impressed with his experiences with wire rope in his pits to put new capital into its future. Heimann’s name then disappeared and the firm was known for the next six or seven years as W Küper & Company, ‘Original patentees of the Untwisted Iron Rope’. The firm expanded quickly under the managing partner, R A Glass; an office was opened at 115 Leadenhall Street in the City of London, the wire rope works on the Grand Surrey Canal expanded and new manufacturing premises established at Morden Wharf on the river Thames at East Greenwich. Their iron wire rope found a considerable market as traction cables in mines and as standing (fixed) rigging for masts on sailing ships, so much so that by the 1850s the Royal Navy divided their contracts exclusively between Smith and Küper.

W Küper & Company quoted for making the armoured shore ends of a telegraph cable across the Irish Channel in 1853 but this did not proceed. There was a request to extend Heimann’s iron wire rope patent in 1854 on the grounds that there had not been time to effectively work it. This was denied by the English courts. In the same year W Küper & Company made and laid its first submarine cable, between Sweden and Denmark; then succeeded in being let the contract for the cable armouring work in that year for the Mediterranean Electric Telegraph Company connecting Italy, Corsica and Sardinia, the longest underwater circuit yet attempted.

George Elliot

The firm became Glass, Elliot & Company in 1855 and in that year made underwater cables for Egypt to cross the Nile, one between Italy and Sicily and another between Newfoundland and Cape Breton. In the next few years there were contracts in North America, Norway, Italy, Romania, India, and between England and Holland, Hanover, Denmark and France. Between January 1854 and October 1863 the firm made and laid 3,929 miles of cable, all of which were successful, and still working in the latter month. Only the Atlantic cable of 1858, which it manufactured one half, with R S Newall & Company the other half, had failed.

R S Newall regarded the competition offered by Glass, Elliot & Company with fury. He was outraged when the new firm shared manufacture of the first Atlantic cable in 1857; more so when the cables in the Mediterranean and Red Seas that he sponsored and made in 1858 and 1859, excluding their competition, immediately failed. Final disgrace came in 1861 when the courts heard that his London agent, George Boswall, had employed a man to infiltrate the laying crew on the Electric Telegraph Company’s steamer ‘Monarch’ when it laid a new line from England to Holland in 1858 with a new heavy-duty Glass, Elliot cable; the man admitted to driving a nail into the cable as it went into the sea damaging one of its four cores. Newall abandoned the making of submarine cables and sold the good will of that part of his business to Siemens, Halske & Company, the British arm of the great Prussian electrical engineering concern, who had worked with Newall since 1858 advising on technical matters and verifying the electrical quality of his cables. In the fullness of time Siemens were to become one of the chief players in the cable business, but not before Georg Halske withdrew from the English concern in protest at the risks that he anticipated in taking on Glass, Elliot & Company.

For a period Glass, Elliot & Company had a monopoly of cable armouring. They were joined in the 1860s by the old established telegraph engineering firm of W T Henley & Company, who had commenced in the 1830s making some of the earliest electrical instruments. Its first ocean cable was laid in 1859 to connect South Australia and Tasmania. Henley’s rapidly committed itself to creating an integrated iron-wire plant in North Woolwich to match Glass, Elliot’s on the other side of the Thames but it struggled for business and acquired most of its early cable construction work as sub-contractor to its competitor.

The troubled spouse...

The Gutta Percha Company has a complicated life-line. Its complexities are related to the personality of Charles Hancock. He had a remarkable family. The most renowned member was Thomas Hancock, the founder of india-rubber manufacture. Commencing in 1828 Thomas Hancock patented virtually every machine and process to successfully work india-rubber or, as it was commonly known, caoutchouc. Another of the Hancock family patented india-rubber binding for books, yet another devised the steam omnibus. Charles was an aberration to his engineering heritage in being by profession an artist.

The Gutta Percha Company was created on February 4, 1845 as a partnership between Henry Bewley and Samuel Gurney. From its commencement it manufactured a long list of resin products at works at High Street, Stratford, London, including (and this is a small sample) buckets, drinking mugs, life buoys, flasks, washing bowls, siphons, tubing, carboys, jugs, soles for books and shoes, and driving bands for machinery. From its origin one of its principal products was tubing for all varieties of liquids and gases.

Gutta Percha Company products displayed at

a Telcon cable centenary exhibition held in 1950

Henry Bewley was a manufacturing chemist in Dublin: he and Henry Draper being in partnership as Bewley & Draper, of 23 Mary Street, Dublin, as soda water manufacturers. Bewley had already devised several uses for gutta percha as well as the Company’s tube-making machine. Samuel Gurney was a famous city money-dealer and bill-discounter. Both were distant from the running of the company which in the first twenty years resided in the hands of Samuel Statham, styled ‘superintendent’. So remote were the proprietors the concern was occasionally referred to in the press as ‘Statham & Company’. As with the Hancock family, both partners were adherents of the Society of Friends or Quakers. By 1850 the Company had moved from Stratford to18 Wharf Road, City Road, London; at which location it remained for nearly a century. On the death of Samuel Statham in 1864, Henry Ford Barclay became manager of the Gutta Percha Company. Barclay was Samuel Gurney’s son-in-law and he, too, was a member of the Society of Friends.

Now to the ill-fortuned Hancock connection; in March 1841 Charles Hancock, abandoning his art for the moment, had patented a stopper made of resin for bottles. In April 1845, with the formation of the Gutta Percha Company, he saw a major production opportunity and assigned an exclusive license for its manufacture to Henry Bewley.

As with many industrial and commercial sectors in the period there was a slightly incestuous relationship between the participants in the resin business. So, on May 31, 1845 Charles Hancock, Henry Bewley, Christopher Nickels and Charles Keene came to an agreement to create a pool account from the proceeds of working several patents that they separately owned relating to resin goods in india-rubber and gutta-percha. Keene and Nickels were to have one half of the proceeds of working the patents, Hancock and Bewley the other half. Hancock commuted his share in the patent to a salary of £800 a year on a three year contract with the Gutta Percha Company, which was to end in 1848. Hancock never was a partner in the Company, probably because he was unable to come up with the cash capital needed and Bewley was wary of the competitive Hancock family interests.

As he realised the opportunities that the resin industry offered over art, over subsequent years other patents by Hancock were added to the cartel agreement. The Gutta Percha Company and C Nichols & Company and their licensees undertook the manufacture of his ideas.

Then, on July 29, 1848, Charles Hancock obtained a new patent for improvements in the manufacture of gutta percha. This was for “an apparatus for covering or coating wire or cord to an infinite length with any plastic substance”; a machine that was to unquestionably revolutionise telegraphy. For the first time an electrical conductor, thin copper wire, could be economically insulated with resin to any degree, to any length; such insulated wire was to be used almost immediately for both underground and underwater electrical circuits. In terms of profit it was eventually to subsume all of the other, very considerable, manufacturing activities of the Gutta Percha Company.

At the time of the new patent Hancock had left the employ of the Gutta Percha Company. Bewley, its principal, however, claimed that the original April 1845 agreement regarding patents was still in force and that its rights should be shared by the signatories. The gutta percha patent cartel had been reinforced and finalised on October 2, 1846 by an Indenture between Bewley, Hancock, Nickels and Keene; and it had been amended on May 9, 1850 to include W H Ashurst and Benjamin Nickels, new partners of Christopher Nickels, Keene by then having died.

Hancock consistently rejected this assumption of rights to the new patent and the dispute first went to Arbitration on October 29, 1852. The award was made on April 23, 1853, one quarter of profits were to go to C Hancock, one quarter to H Bewley, two quarters to Nickels and his partners; three trustees were to manage the patents and to grant licenses upon a fee on sales. The arbitration was rejected by Hancock, but its decisions were confirmed as lawful and binding on appeal to the courts in 1855 and the rights to the wire-covering patent had to be divided between the participants of the old agreement, Hancock, Bewley and Nickels.

There is slight satisfaction in recording that Bewley, Gurney, Nickels and his partners, in fact all of the members of the gutta percha cartel, immediately fell out and resorted to law in a series of disputes over division of profits.

All underwater and underground cables manufactured between 1848 and 1863 were insulated with gutta-percha applied to copper wire using Hancock’s patent wire-covering machine. In that time 14,826 miles of submarine cable core had been insulated with gutta percha, for crossing the English Channel, the Irish Sea, the German Bight, the Norwegian fjords, the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, the Nile, the Bosporus, the Straits of Messina, the Gulf of Canso, the Baltic Sea, the Danube, the Atlantic Ocean, the Red Sea, the Indus, the Adriatic Sea, and the Indian Ocean. By far the greatest mileage was made by Bewley’s Gutta-Percha Company at Wharf Road. There is only one (possible) exception...

Christopher Nickels had been an employee of Thomas Hancock in the 1820s. He became a junior partner with Charles Keene as india-rubber manufacturers in Lambeth during the 1830s, patenting several machines for working india-rubber in his own right. The business grew and works were opened at York Road and Guildford Street in Lambeth, with offices at Goldsmith Street in the City of London. By the 1850s the firm had become C Nickels & Company, whose principal product was india-rubber webbing. In connection with this Benjamin Nickels, his nephew, patented in 1853 the ‘adhesive plaster’, on thin elastic webbing, for dressing wounds. It is not known if Nickels, although part owner of the wire patent, actually possessed a wire-covering machine but his firm, trading as the “Gutta Percha Company of Lambeth”, provided several hundred miles of underground and submarine cables for an unsuccessful telegraph company in Ireland during 1853. It is possible that Nickels contracted for the Gutta Percha Company to manufacture the insulated wire for him. It is also likely that the collapse of the telegraph company brought down Nickels’ firm; it had ceased working by 1855, in which year its York Street works passed to the Electric Telegraph Company as a storehouse and its goodwill and rights to Bewley’s Gutta Percha Company.

As a gratuitous aside, it was one of the six partners in C Nickels & Company, Lockington St Laurence Bunn, another india-rubber merchant, who invented and patented the india-rubber wellington boot in 1857.

On his departure from the Gutta Percha Company Charles Hancock recruited his formidable family into capitalising a competitor, the West Ham Gutta Percha Company, on June 1, 1850 at Stratford in east London. Its range of resin products matched that of the original company but it does not seem to have engaged in the manufacture of insulated cables. It flourished under the management of John Branscombe, becoming licensee of further patents for gutta percha products outside of the cartel as well as new machinery and products of Hancock’s design, and expanded to works at 18 West Street, Smithfield in London during 1856, until 1864 when it merged with S W Silver & Company, india rubber manufacturers.

Stephen Winckworth Silver & Company, colonial and military outfitting warehouse, of 66 & 67 Cornhill, London, with works for making waterproof cloth at 33 & 34 Nassau Place, Commercial Road East had been founded in the early 1830’s. The senior partner had five children, Stephen, Frederick, Hugh, Edgar and Walter. In 1846 his eldest son, Stephen William Silver, became manager and in 1855 inherited his father’s interest.

S W Silver & Company transferred their small india rubber fabric-coating works to a green-field site on the Thames at North Woolwich in 1852 so remote that it was locally known as Land’s End; their influence was such that it soon became known as ‘Silvertown’. Their only neighbour was Howard Brothers, glass-makers, who had commenced business in 1851, whose property they absorbed in 1854. In 1859 the firm began promoting their ‘Patent Caoutchouc Telegraphic Insulator’ and their ‘Patent Caoutchouc Insulation for Telegraphic Cable’, these were the results of Hugh Adams Silver’s patents for spiral-winding india-rubber (caoutchouc) around a copper core using steam heat to convert the spiral into a seamless tube, and for making ebonite (vulcanised or hard rubber) insulators for overhead wires. Their success in the new field was such that in 1863 they projected Silver’s India Rubber Works & Telegraph Cable Company, Limited. This name was to be short lived...

The India-rubber, &c., Telegraph Company's Works, Silvertown, London

It was obvious that S W Silver was keenly aware of the overwhelming competition offered by gutta percha and, as the opportunity arose in the following year, he merged his interests with those of Charles Hancock to create the India Rubber, Gutta Percha & Telegraph Works Company, Limited, and added a wiring-drawing and wire rope making component to the already large works at Silvertown. Combining both india-rubber and gutta percha interests this concern was to be the principal, but very much lesser, competitor of the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company for the rest of the century.

The Union

The Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company, Limited, was effectively founded on April 6, 1864 when its memorandum of association was registered. It inherited and expanded the works of Glass, Elliot & Company at East Greenwich, and of the Gutta Percha Company at Wharf Road. The history of its formation and its subsequent heroic success in connecting the continents of the world is told elsewhere on the Atlantic Cable website...

PS: The In-Laws

The firms of Bewley & Draper, soda water makers, in Dublin and S W Silver & Company, colonial outfitters, of Cornhill, London, continued in business until the 1920s. The firm of George Elliot & Company was created in 1864 to take over the manufacture of wire rope, as opposed to submarine cable, at new works in Newcastle and Cardiff, convenient for the many collieries that Elliot owned, and continued for nearly a century.

To place Steve Roberts’ story of the origins of Telcon in context with the British telegraph companies of the time, see his Distant Writing website.