History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy (original) (raw)

Thomas Allan, CE (1812-1883)

Thomas Allan was born in Edinburgh in 1812. He inherited the firm of Thomas Allan & Company, printers and publishers, in that city from his father, of the same name. Allan was until 1861 the somewhat remote owner of the ‘Caledonian Mercury’ newspaper and as well printer of the ‘Encyclopaedia Britannica’. In his own right he first comes to public notice as local secretary and manager to the North of Scotland Fire & Life Assurance Company in Edinburgh in the early 1840s until he quit for more enterprising activities in July 1848. As this time his residence and place of work was at 20 St Andrew’s Square in Edinburgh.

For much of his life Thomas Allan was to be a promoter, an unsuccessful promoter, of joint stock companies connected with submarine telegraphy. Allan made these attempts based on one of his many patents, so that in the 1860s he was Thomas Allan “of light cable fame”, underwater cables without outside armour.

Thomas Allan’s first venture into the voltaic world was the promotion of the Scottish Electric Telegraph Company in December 1848. This was intended to purchase the patent for an improved needle telegraph of Prof Henry Bachhoffner, an eminent physicist in London, for use in Scotland. The telegraph patent of Cooke & Wheatstone did not fully apply outside of England and this allowed Allan an opportunity. The Scots, however, were unwilling to contribute to the scheme, and let the English bring the telegraph to their country. However the Scottish company was to be the first of around ten joint-stock telegraph concerns that Allan was to promote in the next twenty years.

On November 16, 1850 Allan patented his own improved needle telegraph, actually “an application for deflecting magnets or producing electro-magnets”. The essence of the new telegraph was the use of compound magnets in the galvanometers that indicated the messages through their needles. At the Great Exhibition of 1851 he displayed two pairs of his improved galvanic needle telegraphs. It was carefully timed to appear just before the end of the Cooke & Wheatstone patent monopoly in 1851.

The City of London appreciated the need to challenge the telegraph monopoly and Allan found finance to obtain the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company Act in Parliament in 1851, to purchase Allan’s needle telegraph patent, to construct a national network and to introduce a uniform 1s message rate. This had to wait until1853 for Allan to distribute a prospectus requiring a capital of £250,000 to construct its network; although assembling a respectable board of directors and being widely advertised it did not find any shareholders.

In a somewhat childish reaction to this failure Allan wrote and privately circulated a pamphlet entitled ‘Reasons for the Government Annexing an Electric Telegraph System to the General Post Office’ in 1854. This basically reiterated the need for a uniform rate rather than the complex zone rate based on distance that was used by the telegraph companies in Britain and America and by the state-controlled lines in Europe.

He next appears as a supporting engineer to the laying of an underwater telegraph cable between Holyhead in North Wales and Dublin in Ireland during 1852 for the Irish Sub-Marine Telegraph Company. He was then employed by the cable-maker R S Newall, who had just completed the first successful submarine telegraph across the English Channel to France.

Allan’s famous “light cable” was described in United Kingdom Patent 1,889, dated August 12, 1853 “for protecting telegraph wires”. Uniquely it involved protecting insulated telegraph wire, “by means of iron wires so formed into a rope around a central iron wire core, as to leave spaces between the spiral twists of such wires around the core for the reception of the insulated telegraph wires with or without smaller wires or bands of metal exterior thereto”. This was the reverse of the common, and now universal, practice of having several resin-insulated copper conductors at the core of a surrounding spiral-wound iron or steel wire rope; the metallic outer or armour protecting the resin from abrasion and attack by sea life. The Allan light cable was claimed to be more easily managed and not subject to stretching when being laid on the sea bed. He likened its principle “as a bone in one’s arm”. He improved it in the next year by coating the whole exterior with india-rubber, but by the 1860s had adopted gutta-percha as the resin for the interior and exterior coverings.

Allan’s Cables.

Appendix No, 9, Plate No. 3

Report of the Joint Committee Appointed by the Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council for Trade and the Atlantic Telegraph Company to Inquire into the Construction of Submarine Telegraph Cables together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendix. (1861)

See also the note below on Allan’s Light Cables.

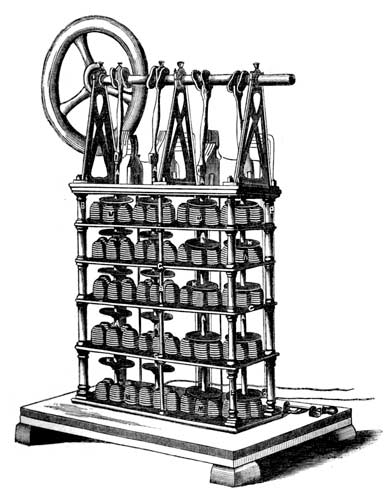

Over the early years of the 1850s Allan was interested in applying electricity to motive power. He took out several patents for improved reciprocating electro-motive engines, culminating in that of September 8, 1855. One of his small electric engines was exhibited at the Paris International Exposition of that year. The French continued to be interested in Allan’s electro-motors and, on April 27, 1857, he attended Napoleon III at the Tuileries palace to demonstrate and explain them to the emperor. Several were to be found running at the workshops of Jean François Cail et Compagnie of Chaillot, Paris, later in 1857.

In Jules Verne’s novel ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’, the author describes the engine of the submarine vessel ‘Nautilus’ as manufactured by Krupp, but its design sounds remarkably similar to that of Allan’s electro-motor, and M Cail is credited with the construction of the ballast tanks!

On May 4, 1857 the Crown Prince of Spain, Don Juan de Bourbon, and his equerry called upon Allan at Adelphi Terrace to be shown the electro-motor and the light cable. Unfortunately none of this imperial and royal interest turned into solid business connections abroad.

Allan's Electro-Motor

Mechanics’ Magazine, March 25, 1854

Thomas Allan demonstrated his electro-motive engine at the Society of Arts in April 1858. An observer gave this description in the following week:

“His plan is to employ a series of magnets, built tier above tier in five strata, each of which, in turn, attracts an iron disc, or keeper, resting loosely upon shoulders projecting from a rod working perpendicularly, and attached at the upper extremity to a crank axle. Each tier of magnets draws down its keeper through about half-an-inch of space, thus employing the maximum of attractive even to the point of actual contact, when the next stratum of magnets comes in to play, acting upon another keeper and impelling the piston rod through another half-an-inch. This process is continued through the whole series; and when the rod has reached the lowest point, a reverse action, though another set of magnets, carrying it up again, and so on perpetually, the machinery itself; by its vibration, establishing or suspending the electric currents through the magnetic strata at the proper moments. The result is to multiply the half-inch stroke into three inches or more each way, a length quite available for conversion through an ordinary crank action, into rotary motion, with a very tolerable economy of power.”

The British Parliament passed new laws in 1855 and 1856 that permitted for the first time limited liability joint-stock companies. The opportunity to use these to recover in monetary terms some of the time and energy that Allan had expended over the previous five years was soon seized.

As well as electric pursuits Allan found time to become a director of the Hull & London Life Assurance Company and the Hull & London Fire Insurance Company with a united capital of £200,000 in December 1855. He had to petition for the winding-up of the two firms in March 1857. Allan also became involved in the British Steam Fisheries Company as a director, another joint-stock promotion destined for oblivion in 1856. It looked for £100,000 to fund a fleet of trawlers to exploit the North Sea fisheries.

More importantly Allan assembled a provisional board of directors from bankers and others involved in Ottoman, Indian, Chinese and Australian commerce in April 1858 and advertised the Great Indian Submarine Telegraph Company to create a line from Falmouth in England to Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria, Aden and Bombay in India. These circuits were to use the patent light cable. It had a capital of £1,000,000 and sought an annual subsidy from the government in London of 5% for the western section and 5% for the eastern section. The government selected others for their support.

With the failure of the initial intercontinental cable of the Atlantic Telegraph Company in 1858 Allan opportunistically leapt on the competitive bandwagon to promote the Great Ocean Telegraph Company. This proposed a long, lightweight cable between Falmouth and Halifax, Nova Scotia. He offered unsolicited advice on the reasons for the cable’s failure.

To the government committee on the Atlantic cable during December 14, 1859 he proposed his own solution to the problems involved:

“Allan’s System of Ocean Telegraphy”

“The principal feature in this system of telegraphy, besides the production of electricity most effective for working extra distances of submerged wire, is a deep-sea rope or conductor, combining the maximum of conducting power and strength with the minimum of bulk, weight, and specific gravity, thereby rendering its safe submergence in ocean depths a simple mechanical operation.”

“The mechanical principle in the construction of these ropes is the reverse of those hitherto used, the peculiarity being that the whole metallic strength is placed in the centre of the insulating medium,—thus forming an inextensible core, and so preserving the insulation from injury by tension, in place of the self destructive spiral wire casing as heretofore.”

“In a cable constructed on these principles, suitable for the distance between England and America, the core or conductor is composed of a solid copper wire, surrounded with steel wires, in itself capable of bearing a strain of 21 cwt without yielding. The weight of the cable is 8 to 10 cwt to the mile, and under 2 cwt. in sea water; its weight, therefore, could not in any degree injure its electrical qualities, as the core or conductor alone is capable of bearing upwards of 10 miles of the cable, hanging vertically from the ship, before the insulating and conducting medium could in any degree be injured by tension.”

“The conducting power is threefold greater than that of the late Atlantic cable, whilst the insulating medium is much thicker, and prepared so .as to withstand heat and pressure.”

“From its lightness and portability, upwards of 3,000 miles can be conveyed in one vessel; and the paying-out gear being dispensed with, it can be veered out at the rate of 8 or 10 miles an hour with facility.”

“From the very great increase in the conducting power and insulation relatively, besides dispensing with the iron envelope hitherto used, a very much higher rate of signalling can be attained.”

“Under this system, it is calculated there will be comparatively an economy of 40 per cent, on the first cost of construction, besides 50 per cent, on the working.”

However the standard of Allan’s technical knowledge may be judged from his agreement to the 1859 committee that there was “no difference in velocity of electricity in iron and copper wire”. His opinions were ignored by the government and by the Atlantic Telegraph Company.

But by 1860 the world was ready for a new domestic telegraph company and the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company of 1851 and 1853 was revived and launched on the public by Thomas Allan. It sought to raise £150,000 for a national network. For once Allan attracted both company sponsors and sufficient finance to get a company beyond the paper world of shareholder prospectuses. Unfortunately for him the board of directors, especially the deputy chairman, Alexander Angus Croll, had fought many corporate battles in previous positions and were too much for Allan, who proved to be an amateur in management.

By his indenture dated July 24, 1860 with the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company dated Allan was to receive £2,000 per annum in salary as electrician and chief engineer, a sum of £10,000 in cash, £15,000 in shares and a royalty of 10% on all net profits on the shares above 5%. There was a clause that enabled the board to give notice if his services were no longer required by the company, this was given on October 3, 1860 and he was obliged to leave their service on January 21, 1861.

Allan sued the United Kingdom company for £20,000 compensation, the balance of what he felt was due under the original contract. The suit was due to be heard on July 5, 1861 but was withdrawn by Allan on the same day. Realising that the company was in poor financial straits he left the suit pending…

Despite this set-back he promoted Allan’s Telegraph & Factory Company from Adelphi Terrace in 1861 to manufacture his patent instruments and his light cables. To publicise this, in the following year, Allan showed a new 'automatic' telegraph that he was developing at the International Exhibition at South Kensington in London, as well as his electro-magnetic engine, his submarine cables and other items. The manufacturing company was abortive.

For much of the 1860s Allan was involved in promoting intercontinental telegraph cables, appearing before Parliamentary committees and speaking at the learned societies. His concept of the “light cable”, weighing nine (0.45 tons) or twelve (0.60 tons) hundredweight to the mile, for ocean-bed use as opposed to the much heavier conventional cables, weighing several tons to the mile, though widely promoted and seriously reviewed was never manufactured. He was also able to attract many City figures in the period in support of his many schemes.

In 1864 the ‘Telegraphic Journal’ wrote in regard to intercontinental communications: “Mr. Thomas Allan proposes a cable of a novel and ingenious construction, dispensing altogether with an external iron coating. The cable consists of a copper conducting wire of a large size, covered spirally with a number of steel wires of gauge 25, and coated with an insulating material of the required thickness, the whole finished in a covering of plaited jute, &c. One of these cables was weighted to 1,787 lbs, and the extension before removing the weights did not exceed 0.67 per cent. The permanent extension upon a length of 20 feet was = 0.234 per cent., the return = 0.443 per cent., and the breaking strain equal to 4,698 fathoms. Other specimens had breaking strains of 6,348 and 7,484 fathoms respectively. Mr. Allan produces a cable which certainly possesses several important advantages besides that of having its element of strength, completely protected from the corrosive influence of water; it is small in bulk, of light specific gravity, great strength, and not liable to kink.” This was an improvement on his original “light cable”.

In need of capital, during 1861 Thomas Allan sold his interest in the family publishing and printing firm to his brother Robert. He in turn, in April 1862, sold the firm to James Robie, the editor of the ‘Caledonian Mercury’, ending the family connection that dated from 1800. It seems that the profits and capital of the family firm went into funding Allan’s researches and into his company speculations.

During March 1864 Allan presented an improved relay and recorder for the Morse telegraph, combined with a new automatic sender using punched tape. All of these were propelled by magnetic power rather than manually or using clockwork. The claim was that sending and receiving rates were increased two- or three-fold. It was not patented or, apparently, utilised in service.

Once the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company abandoned the 1s 0d uniform message rate in 1865 as uneconomic Allan launched the National Telegraph Company with a capital of £500,000, promoting a uniform rate of 6d for 15 words including addresses. The advertising stated that it was to connect London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, York, Hull, Birmingham, Sheffield, Portsmouth and Bristol.

The latter half of the 1860s was a period of great speculation; this allowed Allan to create the Railway Electric Engineering & Telegraph Works Company in 1865 from No 1 Adelphi Terrace, Strand. It was intended to manufacture parts for railway permanent-way, telegraph instruments and light cables for ocean use, for all of which he possessed patents. It, like all his other projections, came to nothing.

On October 13, 1865 he launched Allan’s Transatlantic Telegraph Company, a revival of his Ocean Telegraph promotion of 1858. He sought £150,000 for a cable between England, Portugal, the Azores and Halifax in Canada. This only came about through the brief pause that transpired between the failure to complete the 1865 Atlantic cable and the triumphant success of the 1866 cable, and the recovery and completion of circuit from the previous year.

A year later, on October 16, 1866, in the year of the Great Crash, when the money-dealers Overend, Gurney & Company collapsed and its network of banks and finance companies brought the country to the verge of failure, Thomas Allan was declared bankrupt. His creditors accepted a composition of 7s 6d in the £ (i.e.38%) for his debts.

The newspaper that his family founded in Edinburgh in 1800, the ‘Caledonian Mercury’, published its last issue on April 20, 1867.

On February 11, 1867, despite the disaster of insolvency and the appalling economic climate, Allan contrived to find the resources and willing allies to promote one final joint-stock enterprise to restore his lost fortune: the British & American Telegraph Company. On paper, at least, this was to be substantial concern with a capital of £600,000, intended to connect Falmouth in England with Halifax, Nova Scotia, via the Azores. As well as being registered in England it was incorporated in both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in British North America. The cable, of course, was to be Allan’s light cable, “one quarter of the weight of the Atlantic cable, and one third of the cost”. Allan was to have 5% of the capital as royalty for his rights, and a share of all annual profits above 10%. It was hopeless; Allan was bankrupted for the second time and the petition for the company’s winding-up was presented on October 15, 1867.

He managed for the time being to continue to live at Adelphi Terrace. On August 26, 1867 Allan was found bankrupt once again. He promised to pay off his creditors in two instalments over two years, and had to move from his Adelphi rooms. But he had a desperate scheme; realising that it was about to be taken over by the government and would come into possession of £500,000 as its price, he resurrected the claim against the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company for compensation for his dismissal in 1860. He undertook this action on February 18, 1868, but as in 1861, withdrew the suit on the same day.

Instead he petitioned to wind-up the United Kingdom company as a creditor on June 15, 1869. The court recommended on January 26, 1870 that the liquidators set aside £25,000 out of the £500,000 received by the government as a contingency against Alan’s successful suit. However, the court dismissed his claim on June 28, 1871.

In 1868 a twelve page pamphlet, ‘Adaptation of the telegraph to the Post Office: early letters, dates, and papers thereon’, appeared in Thomas Allan’s name claiming that he had introduced the scheme for appropriating the telegraph to the state in 1854.

During 1870 he self-published yet another sixteen page pamphlet, entitled ‘The title of Thomas Allan, C.E.: to compensation for his efforts to establish a uniform shilling rate for the conveyance of telegraphic messages, on the principle of the postal service, and the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company, Limited’. This appealed to the government for the share of the money that he thought due to him from that used to buy the telegraph companies for the General Post Office.

It did not stop there… Allan eventually sued the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company, individual members of its board and its manager over the same issue eight times; in 1864, twice in 1869, twice in 1871, in 1872, in 1875 and in 1879. Each time he failed. The executor to his will, Joseph Steer Christopher, a 77 year old patent, mercantile and emigration agent (and serial bankrupt), sued them several more times after Allan’s death in 1883. From March 1884 until 1887 Christopher, described as a pauper, and William Hind, claiming to be Thomas Allan’s former partner in business, alleged fraud, perjury, bribery and the like against several board members and the company secretary, adding to these accusations of fraudulent combination and gross and fraudulent misconduct by the Courts of Justice. In addition, in his role as Allan’s executor, in 1889 he began a series of suits again the former directors of the Electric & International Telegraph Company, which company had ceased to exist in 1870, for £1,000,000. This, he represented, was the sum that Allan was defrauded of in the alleged assignment of a cable concession with the Netherlands government in March 1852. The suits carried on until 1893, and cited “one hundred acts of perjury” by the defending directors, several of whom were dead. All the law suits in Allan’s name were complete and utter failures, involving, moreover, slanders and libels that compelled the courts to levy penal costs against Christopher and Hind.

Thomas Allan was married to Geddes, an Englishwoman from London, eight years his junior. They had no living children. He was an enthusiastic member of the Institution of Civil Engineers and of the Society of Arts & Sciences. He died on July 22, 1883 in London.

For most of his life in London he had rooms at No 1 Adelphi Terrace, Strand, overlooking the river Thames. Since the time of Thomas Telford in the 1800s, it was part of a quarter occupied by engineers, surveyors and lawyers connected with public works. As well as accommodating him and his wife, Geddes, it served as the offices of the many companies he promoted. On his financial failure in 1869 he moved with his wife to lodgings in Lambeth.

Thomas Allan’s Patents

No 13,352 of November 15, 1850 - Electric Telegraphs, for deflecting magnets or producing electro-magnets

No 14,190 of June 24, 1852 – Producing electro-motors

No 101 of October 1, 1852 – Using carbonic acid gas to provided motive power

No 339 of February 8, 1853 – Galvanic battery

No 1,889 of August 12, 1853 – Light cable

No 2,243 of October 20, 1854 – Applying electricity for motive power

No 261 of February 3, 1855 - Obtaining and transmitting motive power

No 2,045 of September 8, 1855 – Correcting and preventing deviation in compass needles

No 2,666 of November 27, 1855 – Applying electricity for telegraphic purposes

No 2,519 of October 27, 1856 – Permanent way of railways

No 2,204 of September 29, 1859 – Applying electricity for telegraphic purposes

No 307 of February 6, 1861 – Making animal sinew fibrous (a communication from France)

No 788 of March 30, 1861 – Looms for weaving

No 2,521 of October 2, 1865 – Electro-plating steel

No 2,241 of August 1867 – Improvements in submarine telegraph cables

Allan’s Light Cables

Charles Bright, in the Light Cables section of his 1898 book: Submarine Telegraphs: Their History, Construction, and Working, makes these comments on Allan’s cables:

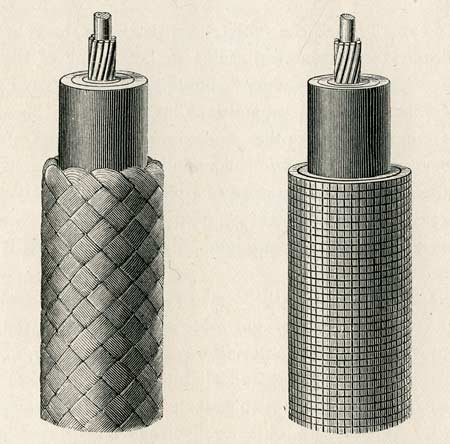

The light cable, however, which attracted the most attention was that of Mr Thomas Allan. This consisted in a solid copper wire surrounded by a number of closely fitting smaller steel, or iron, wires,[1] applied spirally. The conductor so formed was covered with ordinary gutta-percha or india-rubber insulation—the latter at any rate outside — the core being encased in a thin covering of hemp, tarred string, or canvas impregnated with pitch, or marine glue.[2] All these were intended for insulating as well as preservative purposes.

It was claimed for this cable—two forms of which are shewn in Fig. 120—that it combined the utmost lightness (weighing only 353 lbs. per N.M. in sea-water) consistent with necessary tensile strength (2 tons).[3] It was enclosed, moreover, in as small an area as possible, in order to reduce the coefficient of friction to a minimum.

Fig. 120.—Allan’s Light Cables.

The electrical objections to a line of this description are, however, not inconsiderable. The combined metals would form a bad conductor to start with, quite apart from the chemical action which would be likely to occur. Again, the electro-static capacity with so large a conductor would be very great.

Mr Allan’s cable formed the subject of a patent in the year 1853, but it was never adopted on a practical scale : in fact, none of these proposals ever came to anything in practice,[4] nobody appearing to care (when it came to the point) to invest money in what seemed to be at the best a risky affair as compared with other known and tried types of cable which had already been, at any rate, laid successfully.[5] With the light of experience it would seem that the balance of opinion in those days was correct. We have practically adhered to the original type of cable from the beginning—an unusual circumstance in engineering—shewing that it was not the cable that was at fault.

Mr Allan appears to have considered at that time that galvanising had a weakening effect on iron, and his wires were not to be galvanised. In point of fact, in the present day it is found to slightly increase the breaking strain.

Marine glue is a mixture of one part of india-rubber dissolved and softened in mineral naphtha oil, and two parts of gum-lac.

Thus it was said to be capable of vertically supporting in the sea the weight of 12 miles of its own length. Again, not being bulky, a ship of quite medium size could easily carry some 3,000 miles—more than sufficient to telegraphically connect Europe with America. Moreover, the laying could be effected with little risk and without elaborate “holding-back” machinery, the cost of construction added to that of laying being some 40 per cent, less than in the case of an ordinary iron-sheathed cable to meet the same requirements.

It was even claimed that, by such a form of line, the speed would be increased by as much as 50 per cent. The reverse might more reasonably have been expected.

However, in addition to the objections applicable to all light cables, it was remarked with regard to Allan’s cable that the contact of the two different metals in the conductor would be likely to set up serious chemical action.

- There are great objections to absolutely light cables of any species if only on account of their tendency to sink so slowly under ordinary conditions ; and being seriously subject to surface currents, all control over them whilst paying out is lost. Thus, such a cable may be laid on an entirely different—and possibly less safe—route to that intended, and the length of cable wasted is liable to be, in consequence, of much greater value than the initial cost saved in construction.

Again, a cable of this type could never be laid as well at the bottom, and therefore would be of less value ultimately to its owners. In paying out, the ship would require to proceed abnormally slowly under any circumstances, though it must be admitted there would be less risk of putting an undue strain on such a cable (of low specific gravity) in the operation, and the “holding back,” or brake, power required would be correspondingly less.

- In this connection it may be remarked that submarine telegraphy is somewhat at a disadvantage—perhaps more so than many other branches of “heavy engineering”—in that in investing money in any new venture it is being literally sunk at the bottom of the sea; and, if a failure, is not recoverable. Thus, unless a novel type of cable or original method of insulation bears success and advantage on the face of it, an inventor finds great difficulty in obtaining for it a fair trial in practice; though contractors, of course, may often be in a position to try a novelty of their own. Furnished with an extensive practical experience, the latter are, however, certainly the best judges, and anything they attempt in the way of novelty is distinctly more likely to prove a success.

Modern Lightweight Cables

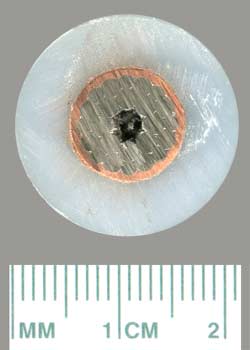

Allan’s proposals for light cables found little favour at the time, but a variation of his design, with its strength member at the center rather than around the outside of the cable, was almost universally adopted for deep sea cables in the early 1960s.

This lightweight undersea cable design was originated by the British Post Office in 1951, and was first used in service on the 1961 CANTAT 1 undersea telephone cable between Britain and Canada. It then soon became the standard design.

|

Detail of core, showing central stranded steel mechanical support surrounded by the copper conductor and polyethylene insulation Detail of core, showing central stranded steel mechanical support surrounded by the copper conductor and polyethylene insulation |

|---|

Even closer to Allan's concept are fiber optic submarine cables, millions of miles of which span the globe today and carry most of the world's communications.

Tyco light weightloose tube cable Tyco light weightloose tube cable |

Image courtesy of Tyco Image courtesy of Tyco |

|---|

The core of this undersea optical fiber cable is a loose tube of a traditional thermoplastic tube material, containing up to 24 optical fibers. Outside the tube, 24 stranded wires form a tight package surrounding the loose tube. Next, copper tape is welded and swaged down on the wires to serve as an electrical conductor and a protective sheath. Then a polyethylene jacket is extruded over the copper to serve as insulation.