Physics be damned, we can’t stop obsessing over NASA’s ‘impossible engine' (original) (raw)

Imagine an engine with nothing powering it. There are no moving parts, nothing appears to be coming out the back, and when you look inside, there’s nothing there either. This is the unbelievable premise behind the "EM drive" — a hypothetical space drive that we’ve been promised might one day take us to Mars, but that experts say is likely the result of nothing more than wishful thinking and scientific error.

"A small effort that has not yet shown any tangible results."

Like the machine itself, the coverage of the EM drive just keeps going and going, propelled, apparently, by nothing at all. A spate of articles earlier this month suggested that NASA itself had tested the drive and found it to work, something that the space agency refuted this week. "While conceptual research into novel propulsion methods by a team at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston has created headlines, this is a small effort that has not yet shown any tangible results," a spokesperson told Space.

People want the EM drive to be real for obvious reasons. It’s cool, it’s exciting, and it’s ludicrously optimistic. The drive was originally created by a British inventor named Roger Shawyer, who claimed if that if you bounced microwaves around a sealed metal container just so, you could create thrust at one end. No moving parts, no propulsion, just thrust. Such an engine would be a godsend for space travel, allowing scientists to build spacecraft without all that stupidly heavy, finite rocket fuel and instead launch something simply with enough solar panels to keep the engine functioning. With a working EM drive we could get to Mars in just 70 days, some have claimed, fulfilling that secular version of salvation — turning humanity into a multi-planetary species.

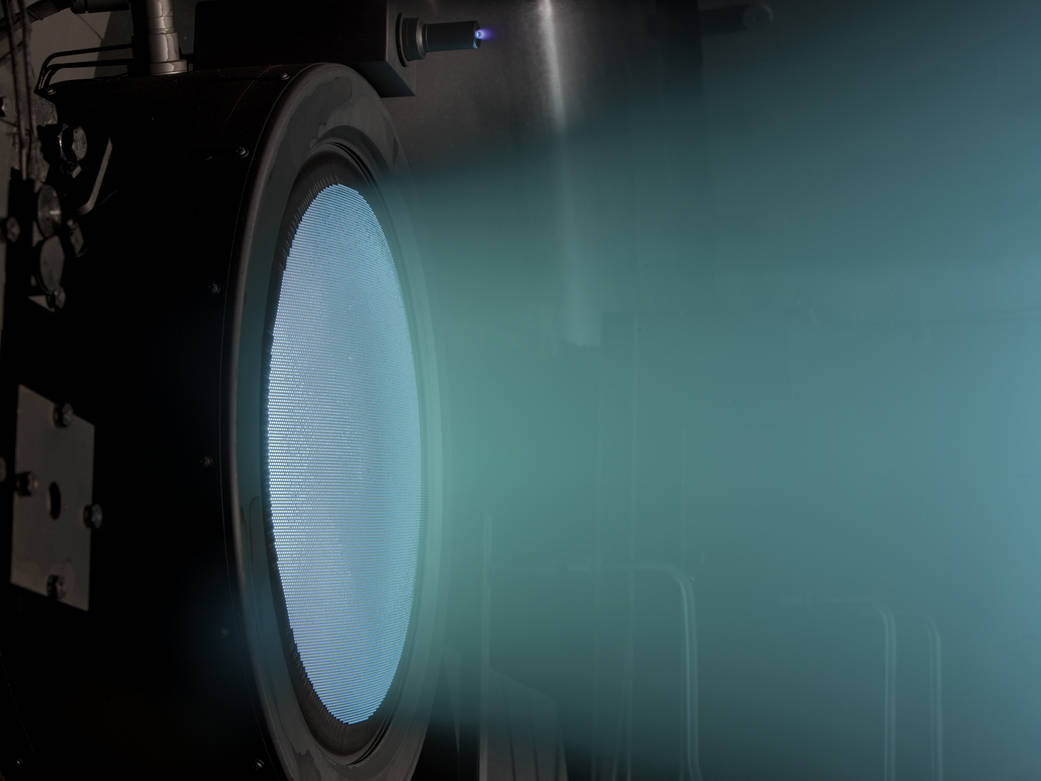

Ion drives may sound like science fiction, but they're very real. (NASA)

Ion drives may sound like science fiction, but they're very real. (NASA)

Except, of course, for the physics. If the EM drive did actually work, it would be breaking some of the most fundamental and thoroughly tested laws of the universe: the conservation of energy and momentum. The first of these states that you can’t simply create energy out of nothing, while the second says that to create movement (which is only a type of energy), you have to have some sort of equal and opposite movement. Scientists who have backed the EM drive over the years are claiming to have created thrust from nothing, therefore breaking both laws at once. The EM drive — if it works — is like a dog straining at the leash, but with no dog. There’s no gas coming out the end (as with regular rockets), nor anything as insubstantial as ions (which is what makes very weak but very real ion thrusters (PDF) work). And yet, say those involved, the drive is creating thrust.

"Like moving your car by pushing on the steering wheel."

"It’s like saying you could get your car moving by sitting inside and pushing on the steering wheel," says Sean Carroll, a physicist and cosmologist at the California Institute of Technology. He adds that none of the explanations for why the EM drive might function make any sense. One of the theories states that the drive is somehow gaining traction by interacting with the "quantum vacuum" — a base layer of reality predicted by quantum mechanics to be full of tiny fluctuations giving rise to energy and matter. This, says Carroll, is entirely meaningless. "It’s a complete misunderstanding of quantum field theory," he says. "The quantum vacuum […] has no inertia of its own. Appealing to it to help explain dodgy experimental results is just a bit of technobabble."

This didn't stop the story spreading. In 2006, after Shawyer had received £250,000 from the British government to build the machine, the EM drive ended up on the front cover of New Scientist. The accompanying article was quickly shot down by various scientists (the magazine itself admitted they should have been clearer that the EM drive "apparently contravenes the laws of physics"), and Shawyer disappeared from the story, but the ball was simply fumbled forward.

"NASA validates 'impossible' space drive."

In 2012, a Chinese team of scientists claimed they’d built their own working EM drive capable of producing a tiny amount of thrust without using any propellant. This produced a murmur of press coverage, but nothing too substantial. But then, in 2014, a marketing executive-turned-inventor named Guido Fetta said that he’d created his own version of the machine — rebranded as the "Cannae Drive" — that also worked. Fetta’s machine was tested by a small team of scientists from NASA Eagleworks — a group that focuses on advanced propulsion technology for spacecraft — who said that yes, amazingly, this thing was producing thrust. And while the drive seemed to be less powerful than in the Chinese experiment, it was still a staggering find. With this, the EM drive really took off, with a first report from Wired UK claiming that "NASA validates ‘impossible’ space drive." Various articles followed on a similar theme, many of them taking an appropriately skeptical stance, but giving credence to the claims nonetheless.

A prototype of the EM drive. (Roger Shawyer/EMdrive.com)

A prototype of the EM drive. (Roger Shawyer/EMdrive.com)

However, as Discover Magazine pointed out in a thorough debunking of the entire concept of EM drives last year, the science produced by NASA Eagleworks just doesn’t stand up. Even ignoring various methodological ambiguities — especially over which parts of the test took place in a vacuum — the paper reported that thrust was generated by a version of the EM drive that was designed not to work. The difference between the two drives was that one had slots engraved in one side designed to create an "imbalance" in the microwaves (and thus, the theory goes, thrust), while the other had no slots. The fact that both versions were found to be creating thrust could suggest that the scientists involved don't quite understand what they've created, or that they made a mistake.

Carroll says that the effects that the test was supposed to measure were small enough that they could easily have been created by a wide variety of experimental errors. A recent report, for example, revealed that radio signals of "terrestrial origins" supposedly picked up by Australian telescopes actually originated from a staff microwave. "Experimenters make small mistakes all the time," he says, pointing to an infamous experiment from 2011 that appeared to show neutrinos moving faster than the speed of light. "Real physicists knew it was nonsense from the start, but it caused a big media ruckus," says Carroll. "In the end, of course, the results were traced to some loose cables."

No papers concerning the EM drive have ever been submitted for peer review

That was last year, but the EM drive’s latest burst of speed is, unfortunately, no more credible. Last week, an article published on NASASpaceFlight highlighted claims made on the site’s forums by NASA Eagleworks scientist Paul March. March said on the forums that the EM drive had been tested yet again, this time in a vacuum, and it still worked. This test supposedly ruled out one of the ways that the drive might have been producing false results, with the "thrust" actually created by outside heat sources. Many publications — including this one — wrote up the claims, even though nothing of substance had been added to the body of evidence supporting the EM drive. Notably, no paper purporting to show the drive functioning has been submitted to a peer-reviewed publication. Carroll, who hasn’t been involved with NASA Eagleworks’ experiments, says this is because the science is so clumsy — the methodology unclear, the explanations so nonsensical — that no paper on an EM drive would be accepted.

We really, really want to the believe the EM drive is real

So why do we keep on falling for this story? People really want to read about a NASA-approved space engine that not only breaks the laws of physics, but might also be the key to getting humanity off this rock. But there’s also more to it: for a start, while the basic concept of the EM drive is easy to grasp (magic box makes movement out of nothing), the supporting theory belongs to a realm of science that is, itself, kind of unbelievable. When you’re hanging out at the extremes of human knowledge, where even the experts are arguing among themselves about what's true, it can be hard to get a proper grip on what is a legitimate claim and what isn’t.

The fact that the papers supposedly validating that the EM drive works were published by NASA also has something to do with it, even though — as has been pointed out many times before — the space agency is a vast organization full of many moving parts and even then, is capable of being wrong. It funds all sorts of exotic-sounding experiments, and a few short papers published by a small team isn’t the same as the official party line. Unfortunately, what it does mean is that publications can attribute the work to NASA, and thus associate the results with what is a well-funded, rigorous, and trusted government body.

We know that we really want an impossible space engine to work, and we know that so far there’s just not enough evidence for it. "The strongest bias we have is to believe things that we want to think are true," says Carroll. "Therefore, one of the tenets of doing good science is treat ideas that we want to be true with the highest levels of skepticism. What we're seeing here is the opposite of that. I would love to have warp drive or cheap space travel. I'm just not willing to throw out the laws of physics the first time someone claims to have built a machine that would make it possible."