The Anti-Imperialist The Whitewash of Black Beauty | Ceasefire Magazine (original) (raw)

A few days ago, Dr Satoshi Kanazawa, of the London School of Economics announced, to the consternation and shock of many, that women of African descent are less attractive than women from other ethnic groups. Ceasefire associate editor Adam Elliott-Cooper interviewed two Black Feminist activists to discuss the Kanazawa furore and develop an understanding of our racialised perceptions of beauty.

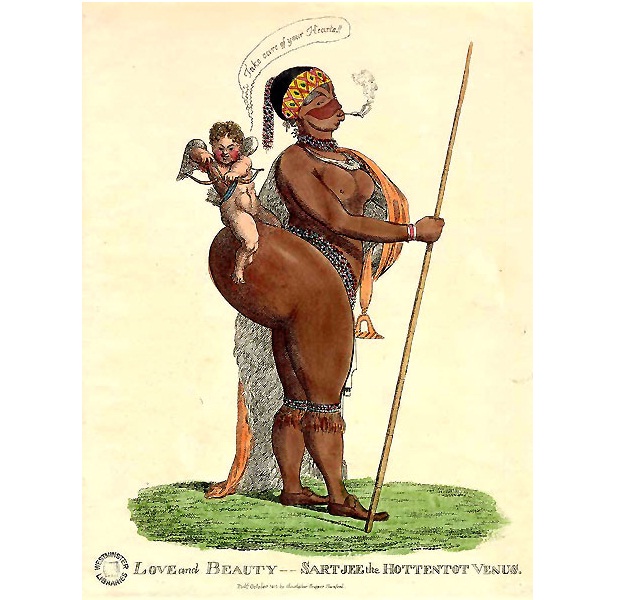

An 18th Century caracture of Sarah Baartman, a.k.a the “Hottentot Venus”.

By Adam Elliott-Cooper

Aesthetics are an integral part of the way we make sense of the world, as well as make sense of ourselves. They can influence our perceptions of a person, event or environment and, in turn, these perceptions can be influenced by what we see. Importantly, the society in which we live shapes how we perceive the things we see – with historical, cultural and socio-political indicators constantly contextualising our world.

This contextualisation was overlooked by Dr Satoshi Kanazawa of the London School of Economics in his recently published article in Psychology Today, in which he claimed that women of African descent were uglier than those of other racial groups. This was done by showing different photographs of women from various ethnic backgrounds to a sample of men, and asking these men to rate the attractiveness of each woman.

The complex histories which result in European hair, or fairer skin, being associated with beauty cannot be reduced to a psychological decision made by a human being – these are subjective perceptions that had been shaped by hundreds of years of conditioning. “I would marry her were she an Ethiope” exclaims Shakespeare’s Claudio to prove the depth of his love in Much Ado About Nothing.

African slaves of a lighter complexion were awarded jobs in the home or office rather than the field, such as Richard Wright’s grandmother, as described in the semi-autobiographical Black Boy.

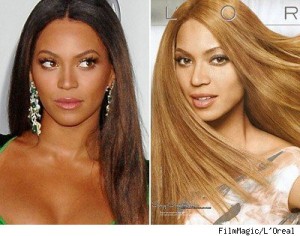

Centuries later, these assumptions of lighter complexions reflecting beauty and other forms of superiority have been internalised to the point of becoming widely accepted truisms. Straight, often lightened hair and fairer skin dominate mainstream images of Black female beauty.

In order to deconstruct these assumptions, and help build an understanding of an approach to human aesthetics which transcend racialsed assumptions and stereotypes, I spoke to two Black Feminist writers and activists; Hana Riazuddin and Rukayah Sarumi.

What is the significance of Black feminism in understanding western concepts of beauty?

HR Understanding concepts and constructions of beauty for Black feminists is really and truly about locating women of colour within a complex myriad of power relations, their experiences and ultimately its effects.

For the most part, western concepts of beauty not only advocate a patriarchy that determines the worth/role/place of women in general, but for Black women in particular it is precisely such constructions that have been used to devalue and ultimately dehumanize them. Many people forget that the White Supremacy that accompanied colonization and slavery was founded and dependent on the academic work behind race and ethnology.

Stories like that of Sarah Baartman, also commonly known as the Hottentot Venus, provide ample examples of just how racialised constructions of beauty have shaped and placed women of colour within a broader framework of power and hierarchy to reinforce White Supremacy as a system of domination.

Similarly, Black feminism seeks to look at individuals holistically. Breaking down western concepts of beauty and the implications it has had on Black women is as much about looking at how it effects self-esteem, self-worth, value, purpose and power in the quest of undoing systems of domination on a personal level as it is about challenging them on a political level.

In giving voice to Black women’s voices and experiences, they turn women who are often objects of such discourse into authentic agents, illuminating the political and social tensions of westernized notions of beauty and ultimately the interlocking systems of domination that give way to them. Black feminism demands recognition of this and questions White privilege in sustaining interlocking systems of domination.

RS Further to this though, we can actually begin to consider, things such as beauty. Why is beauty the central point of consideration when it comes to women of all races. Why is it that women can constantly be interrogated, analysed and assessed on matters pertaining to our physical appearance.

We must note that it was Black Women that Dr. Kanazawa chose to conduct his ‘scientific’ research into. He also made a reference to the hyper attractiveness of Black men— an idea that stems from colonial constructs. Yet women were the basis of his investigation. Black feminism allows us to really say; discussing black women, women in general, as vessels of aesthetic pleasure is not enough. Basically we need to start discussing women as entire beings— humans.

How have Eurocentric concepts of beauty shaped gender and sexual politics for Black women living in the West?

RS The other day, my best friend and I sat down and spoke about how disturbed we are by the lack of representation of Black Women in loving relationships on British television. In many ways Black women are seen as the antithesis to beauty and so instead, are often subject to classifications as vixens, hyper sexual or alternatively bitter and undesirable.

When we consider traditional constructions of beauty, and attractiveness; being the damsel, the timidity, ‘delicate’, these are adjectives that are rarely applied to Black women, of course we know that these ideas are in many ways nonsense, but they still have a resounding influence on the way we discuss and identify beauty. Again note that Kanazawa said that the challenge to our attractiveness is a case of a higher proportion of testosterone. He alluded to Black women being more ‘masculine.’ Thus far away from the ‘feminine’ and in turn ‘ugly’.

HR Ideas about beauty have been constructed, packaged, renegotiated and now in collusion with capitalism have been sold to us as readily consumable products, lifestyles and ideas. Concepts of beauty, let alone Eurocentric ones, dictate and determine a gender politics for all women dependent on desirability, notions of femininity and ideas of what or who a woman should be.

For Black women this is a double-edged sword where gender and sexual politics is ultimately racialised and Dr Satoshi Kanazawa’s recent article in Psychology Today is an excellent example of how these ideas are reinforced academically. Black women’s bodies in the West have been the grounds for public speculation and degradation for centuries, dismissing the idea that binaries such as the public/private separation exist for gender or sexual politics.

Black women’s experience of gendered issues and sexism may have much in common with mainstream or white feminism but they are undoubtedly unique and contextual.

When we look at say for example at the Black hair care industry or skin complexion/colourism and skin bleaching, when we analyse music videos and what type of Black beauty is ‘accepted’ within Black communities as well as by White mainstream media, we reveal a world in which ideas of beauty are placed within a historically racist as well as gendered framework.

Here Black women’s worth and place is determined by both gender and race, and neither are mutually exclusive. For White women Eurocentric concepts of beauty do not have the same impact. For Black women living and growing up in the West it is pertinent that we address both if we are to liberate ourselves from gendered and sexist binaries, if we are to live as real, full, human beings with agency, worth, purpose and power – something the mainstream Feminist movement has failed to take seriously for far too long.

African-American feminists have written at length about the racialised concepts of beauty in the US. In what way do these legacies relate to Black women in the UK?

HR When I discovered Black feminist work as a South Asian Muslim woman growing up in the UK it really hit home. Despite the fact that much of the work I was reading from Patricia Hill Collins to bell hooks, or the documentaries I was watching that poignantly explored racialised concepts of the beauty were about the African-American experience, an experience historically extremely different to my own, I began to see just how far reaching and global Eurocentric ideas of beauty were.

As colonized peoples I think we can relate to these legacies and although context/nature of these constructs may vary in depth or degree, what they reveal is how interlocking systems of domination have been used to frame women of colour and continue to do so. These ideas are almost unavoidable and they affect our lives on multiple levels, the personal remains extremely political particularly for diasporic communities for whom self-determination remains key in the face of oppression, exploitation and inequality. bell hooks on issues of gender and race in popular culture

How has seeing Black Female identity though the eyes of white supremacy affected how Black men relate to Black women in the west?

RS My goodness, this can be a discussion all on its own. What I will say, is that I think it imperative that Black men continue to work to resist negative perceptions of Black women. Black men must continue to consider the cross sections between race and gender and really support the efforts against patriarchy and racism.

I believe that one of the biggest problems that has afflicted the Black community is the perceived tension between the fight against racism and that of sexism. Black men too, have a responsibility to see and acknowledge Black women and really join in the fight against unjust barriers against women.

What is being done to help Black men and women to understand why they are identified in such a way?

RS This! Discussions such as this one are happening everywhere. Asking the right questions allows us to truly consider the way our reality is being constructed and I hope give us the impetus to do something about it.

But it is not just the why,. Many are actively doing things to change these perceptions too. Writers such as Nichole Black, whose writing actively dissects the fallacies that haunt all the negative stuff said about black folk.

Artists like Kehinde Wiley, his work really makes us question and reconsider the way we perceive Black physical appearance. The aforementioned writers and academics, in addition to a wide range of male and female teachers and community workers who work tirelessly to engage young people in challenging their perceptions of race, colour and gender. So much continues to be done.

Hana Riazuddin is a black muslim feminist, writer and blogger.

Rukayah Sarumi is a womens’ rights activist.

Adam Elliott-Cooper, a writer and activist, is Ceasefire Associate editor. His column on race politics appears every other Sunday. He tweets at @adamec87.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.