Diougan Gwenc'hlan (fr/en) (original) (raw)

R�sum� C'est avec ce chant que s'ouvrait la premi�re �dition du Barzhaz, celle de 1839, avant qu'il ne soit "supplant�" par les "S�ries" en 1845. Gwenc'hlan est un barde qu'un prince chr�tien retenait prisonnier apr�s lui avoir crev� les yeux. Ayant le don de proph�tie, il pr�dit qu'il sera veng� par un prince pa�en. C'est la vision d'un sanglier bless� (le prince chr�tien), entour� de ses marcassins qu'un cheval de mer blanc aux cornes d'argent (le prince pa�en) vient frapper furieusement, r�pandant une mare de sang. Autre vision: le barde est couch� dans sa tombe. Il entend l'aigle appeler ses aiglons et tous les oiseaux du ciel pour venir se repa�tre de chair chr�tienne. Un corbeau est occup� � arracher ses deux yeux rouges de la t�te du chef de guerre qui a emprisonn� et fait aveugler le po�te. Un renard d�chire son c�ur hypocrite. Quant � son �me, elle ira habiter le corps d'un crapaud.

Contrairement � la pi�ce pr�c�dente, ce po�me n'a jamais �t� collect� par d'autres que La Villemarqu�. La plupart des folkloristes, en particulier Francis Gourvil qui d�couvrit en 1924 un "Chant Royal" dont l'existence �tait annonc�e par deux auteurs du XVIII�me si�cle, consid�rent le "Gwenc'hlan" du Barzhaz comme une forgerie fabriqu�e par le jeune chartiste � partir de r�miniscences litt�raires, en particulier galloises. Ces derni�res deviennent pour lui une r�f�rence de pr�dilection apr�s sa participation � l'"eisteddfod" de 1838 � Abergavenny. Un examen attentif de ce "Chant Royal", du po�me du Barzhaz et des commentaires qui l'accompagnent, d'une lettre de la ni�ce du Barde, Camille de La Villemarqu�, ainsi que d'un texte d'un autre de ses d�tracteurs habituels, Anatole Le Braz, conduisent � r�viser ce jugement p�remptoire et � conclure, m�me s'il est absent des manuscrits de Keransquer, � l'existence possible, sinon probable d'un authentique po�me populaire � l'origine de ce texte magnifique.

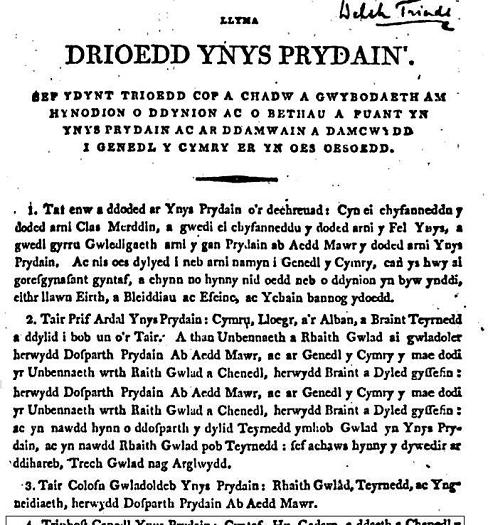

Le Guinclan des dictionnaires En 1834 les �rudits bretons s'int�ressaient � un myst�rieux manuscrit: "les proph�ties de Guinclan" (Guiclan ou Guinclaff) consid�r� comme disparu, depuis la R�volution, de l'abbaye b�n�dictine de Land�vennec o�, au dire du linguiste Dom Le Pelletier et du Capucin Gr�goire de Rostrenen, il �tait conserv� autrefois. Tous deux auteurs de dictionnaires bretons, ils avaient, l'un fait des citations, l'autre mentionn� l'existence de ce texte.

- Dom Louis le Pelletier (1663 - 1733) est l'auteur d'un "Dictionnaire de la Langue Bretonne" qui fut publi� apr�s sa mort, en 1752 et dans lequel il mentionne qu'il avait eu entre les mains, � l'abbaye de Land�vennec, ledit manuscrit o� il avait trouv� des mots pour son dictionnaire (�tant n� au Mans, il n'�tait pas bretonnant de naissance). Dom Taillandier qui r�digea la Pr�face de l'ouvrage posthume avait indiqu� (page VIII) que

" le plus ancien [monument �crit en langue bretonne] qu'ait trouv� Dom Pelletier est un manuscrit de l'ann�e 1450, qui est un recueil de pr�dictions d'un pr�tendu proph�te nomm� Gwinglaff. Il a tir� quelques secours de la vie de Saint Gu�nol�, premier abb� de Land�vennec..."

Gwinglaff est effectivement cit� � trois reprises dans ce dictionnaire:

- aux mots "bagad" ("troupe")

Le pluriel est 'bagadou' qui se trouve pour 'des troupes dans les Proph�ties de Gwingl�f, qui pr�dit:Ma'z marvint oll a strollado�,War Menez-Br�, a bagado�. Qu'ils mourront tous par bandesSur le M�nez-Br�, par troupes. - "gnou" (notoire) -et "orzail" , (="batterie", corruption, dit Le Pelletier du fran�ais "assaillir") - Avant que l'ouvrage ne soit publi�, un autre religieux, le capucin Gr�goire de Rostrenen (1667 -1750) avait fait para�tre son "Dictionnaire Celto-Breton" en 1732 o� il citait ce m�me Guinclan:

1� Dans l'introduction: Liste des...auteurs dont je me suis servi pour composer ce dictionnaire:

"Ce que j'ai trouv� de plus ancien sur la langue... bretonne a �t� le livre manuscrit en langue bretonne des Pr�dictions de Guinclan, astronome breton tr�s fameux encore aujourd'hui parmi les Bretons qui l'appellent commun�ment "le Proph�te Guinclan". Il marque au commencement de ses pr�dictions, qu'il �crivait l'an de salut deux cent quarante (240), demeurant entre Roc'h-Hellas et le Porz-Gwenn: c'est au dioc�se de Tr�guier, entre Morlaix et la ville de Tr�guier"

2� A l'article "Guinclan", page 480 du dictionnaire qui comporte plusieurs noms propres:

"Guinclan, proph�te breton, ou plut�t astrologue qui vivait dans le 3�me si�cle, [et] dont j'ai vu les pr�dictions en rimes bretonnes � l'abbaye de Land�vennec entre les mains du R.P. Dom Louis Le Pelletier.".

Sa lecture ne dut pas �tre tr�s attentive, car il ajoute:

"[Il] �tait natif de la comt� de Go�lo en Bretagne armorique [la r�gion qui s'�tend de Paimpol � Saint-Brieuc] et pr�dit aux environs de l'an de gr�ce 240, (comme il le dit lui-m�me), ce qui est arriv� depuis dans les deux Bretagnes [dans la traduction bretonne de l'article: 'en Armorique et en Grande Bretagne']."

La contradiction avec le futur dictionnaire de Dom Le Pelletier dut lui �tre signal�e, peut-�tre par ce dernier, car 6 ans plus tard, dans sa "Grammaire Celto-Bretonne" (1738), il la corrige partiellement:

"Il s'est gliss�...dans mon Dictionnaire...une tr�s grosse [erreur]: C'est au mot Guinclan dont j'ai marqu� les pr�dictions � l'an 240 au lieu qu'il faut mettre 450."

3� Notons, pour �tre complet que le mot "pr�diction", page 749, contient le renvoi (Voyez G�inclan), article qui contient effectivement la traduction propos�e ici "diougan". - L'erreur n'�tait plus que de 1000 ans! Les commentateurs qui s'int�resseront � Guinclan par la suite retiendront cette date: "l'an 450". C'est le cas de Cambry dans son "Voyage dans le Finist�re" (1797) et de l'Abb� de la Rue dans ses "Recherches sur les Bardes" (1815).

Le Guinclan de Miorcec de Kerdanet

C'est surtout le cas de Daniel-Louis Miorcec de Kerdanet dans ses "Notices Chronologiques..." (1818) o� l'on peut lire (pp. 8-9): - [Guinclan] pr�dit vers l'an 450, les r�volutions des deux Bretagne et la gloire dont il devait jouir dans la post�rit�;

"L'avenir... entendra parler de Guinclan. Un jour les descendants de Brutus [= les Bretons] �l�veront leurs voix sur le M�nez-Br�. Ils s'�criront en regardant cette montagne: 'Ici habita Guinclan'. Ils admireront les g�n�rations qui ne sont plus, et les temps dont je sus sonder la profondeur."

La Villemarqu� a repris cette phrase de confiance dans la "Bibliographie bretonne" de Levot (1852). Il est ais� de d�montrer qu'il s'agit -l� d'une paraphrase de la "Guerre de Carros", tir�e de la traduction par Le Tourneur d'"Ossian, fils de Fingal" de McPherson:

"L'avenir entendra parler d'Ossian. Un jour les descendants du l�che �l�veront leurs voix sur Cona. Ils s'�crieront en regardant ce rocher: 'Ici habita jadis Ossian'; ils admireront et les g�n�rations qui ne sont plus et les h�ros que j'ai chant�s." - Miorcec ajoute:

"Guinclan avait annonc� la peste qui d�sola Guingamp et ses environs en 1486:

"Ma'z marvint holl a strollado�

War Menez Br�, a bagado�."

C'est-�-dire:

"Qu'ils mourront tous par bandes

Sur M�nez-Br�, par troupes."

Cette citation est tir�e du mot "Bagad" du Dictionnaire de Le Pelletier, p.33, o� il est seulement dit que le pluriel "bagado�" pour "des troupes" se trouve dans les Proph�ties de Gwingl�f".

Lesdites "Proph�ties", red�couvertes en 1924, s'int�ressent effectivement avant tout au sort de Guingamp entre 1570 et 1588. Mais dans ce document, les troupeaux humains qui p�rissent sur le M�nez-Br� (� 20 km de Guingamp) sont les Bretons enr�l�s de force par les Anglais. La Villemarqu�, quant � lui, citera la m�me phrase en l'appliquant aux pr�tres catholiques. - Guinclan est encore mis � contribution par Miorcec dans son "Histoire de la Langue des Gaulois" en 1821 (pp.33-34):

"En 450 parurent les "Proph�ties" bretonnes de Guinclan, barde et devin du pays de Tr�guier. Son animosit� contre les pr�tres lui valut le surnom de "Guinclanff" ou "Quinclanff" qui veut dire chien enrag�. On assure qu'il viendrait un temps o� les ministres de notre sainte religion seraient poursuivis comme les b�tes fauves. C'�tait presque l'annonce des malheurs de la R�volution." - Kerdanet reprend ces �l�ments dans son �dition des "Vies des Saints de Bretagne", d'Albert Le Grand, qui para�t � Brest en 1837. Il "traduit" en Breton la fameuse phrase � propos des g�n�rations qui ne sont plus et les temps que je sus sonder":

"An amzerio� tremenet

Hag an dud diskilhet..." - Il ajoute que son h�ros se fit enterrer sous le M�nez-Br� et d�fendit, comme jadis Nostradamus, qu'on ouvre jamais sa tombe, car si l'on troublait son repos, il bouleverserait l'univers.

- Il lui pr�te aussi une pr�diction promettant aux d�fricheurs des pires terres qu'avant la fin du monde, elles produiraient le meilleur bl�. Comme on le verra plus loin, elle figurera, elle aussi, en bonne place dans le Barzhaz. Et, chose bien plus �tonnante, dans le "Dialogue" d�couvert en 1924.

| Abarzh ma vezo fin ar bed;Falla� douar ar gwella� ed. | Que sorte avant la fin du monde Le meilleur bl� d'un sol immonde.. |

| ----------------------------------------------------- | -------------------------------------------------------------------- |

C'est donc, plus que le p�re Gr�goire et son erreur de date, Miorcec de Kerdanet qui est le grand responsable de toute la fantasmagorie autour du fameux proph�te du V�me si�cle qui enflamma tant d'imaginations et en particulier celle du jeune La Villemarqu�.

La soi-disant d�couverte de La Villemarqu�

Comme on le verra � propos du premier chant qu'il publia, "la Peste d'Elliant", le jeune chartiste avait eu en 1835 un entretien avec Miorcec � sa r�sidence de Lesneven. Il fut certainement question dans leur conversation du myst�rieux proph�te, car, dans le post-scriptum de la lettre qu'il lui envoya le 20 septembre, il lui demandait:

"Poss�dez-vous maintenant Gwinclan? Quel est l'�ge de ce monument si curieux?"

- Or, � la m�me �poque l'Inspecteur g�n�ral dans l'administration des Beaux-arts, Prosper M�rim�e avait �t� charg� par le Ministre de l'Instruction publique de s'informer de l'existence du fameux manuscrit aupr�s des biblioth�caires de Bretagne et d'en n�gocier l'acquisition. Il fut inform� le 15 ou le 16 septembre par un de ses amis, le comte de Carn�, en arrivant � Quimper, que ledit manuscrit aurait �t� d�couvert, non par Miorcec, mais par La Villemarqu�. L'Inspecteur se r�jouit, semble-t-il de l'�v�nement annonc� et avait poursuivi sa route vers le sud-est, d�s le 18 septembre.

- Malheureusement, un mois plus tard, un journal l�gitimiste de Nantes, l'"Hermine", qui avait annonc� la fausse nouvelle de la d�couverte le 16 octobre 1835, (imit� en cela, les 28 et 29 octobre, par deux grands journaux parisiens, le "Courrier Fran�ais" et le "Journal des D�bats", qui reprenaient les m�mes fautes d'orthographe que leur mod�le: "Delaville-Marqu�" et "Quin-Clan") faisait part � ses lecteurs, le 30 octobre, d'un incident: lorsque le jeune homme muni d'une autorisation de l'�v�que de Quimper vint prendre copie du document exhum� dans une �glise des Montagnes Noires, ce fut pour apprendre que ce pr�cieux papier avait �t� enlev� par M. M�rim�e. Les adversaires du gouvernement d'alors, en particulier la revue "La Mode" s'empar�rent de l'information pour vilipender le minist�re Guizot.

Francis Gourvil, l'auteur d'une volumineuse �tude publi�e en 1960 sur "La Villemarqu� et le Barzaz-Breiz", voit dans le silence du jeune La Villemarqu� la preuve d'une duplicit� pr�coce... - Il semble que ces fausses nouvelles aient repos� sur une confusion:

Dans une lettre, sans doute du premier semestre de 1835, Mme de La Villemarqu� �crit � son fils: "J'ai parl� au vicaire de Dirinon. Plusieurs personnes ont donn� de l'argent pour retrouver Guinclan".

R�ponse du recteur en janvier 1836:

"...Jamais notre fabrique n'a poss�d� ce fameux manuscrit et tout ce que les journaux ont d�bit� � ce sujet n'est qu'un tissu d'erreurs...On a confondu la vie de Sainte Nonne, patronne de la paroisse avec les �uvres de votre compatriote..." (La vie de Sainte Nonne, "Buhez Santez Nonn" fut publi�e en 1837 par l'Abb� Sionnet avec une traduction du grammairien Le Gonidec. Ces lettres sont cit�es par F. Gourvil dans la "Nouvelle Revue de Bretagne", num�ros de mai et juillet 1949)

La pol�mique avec M�rim�e

Une entrevue eut lieu entre les deux hommes en janvier 1836 qui mit fin en apparence � l'incident. Mais on peut supposer que le franc-parler de M�rim�e ne manqua pas de blesser profond�ment l'amour propre et la fiert� du jeune Breton. M�rim�e se vengea en publiant un rapport,"Notes d'un voyage dans l'ouest de la France", o� il reproche aux Bretons, en d�pit de leur patriotisme provincial, de n'�tre pas pr�occup�s par la sauvegarde de leurs monuments et expose qu'il appartient au gouvernement de pr�cher l'exemple.

Cette pol�mique o� s'exacerba le nationalisme local du jeune homme, a nuit � sa carri�re d�butante, en pr�venant contre lui des �crivains de renom: Sainte-Beuve qui le premier met en doute "l'exactitude...de ses recherches...et l'esprit critique qui y aurait pr�sid�", et Lamartine dont il ne re�ut jamais que de vagues encouragements.

Ayant essuy� un refus de la part de la "Revue des Deux- Mondes", cr��e en 1830, il fait para�tre dans l'"Echo de la Jeune -France", le 15 mars 1836, un article intitul� Un d�bris du bardisme accompagn� du chant La Peste d'Elliant qu'il datait du 6�me si�cle.

Cet article r�pond aux agressions verbales de M�rim�e et contient "tout le Barzaz Breiz en puissance", comme l'a �crit le linguiste F. Gourvil.

On y trouve en effet des envol�es lyriques telles que:

"Aujourd'hui qu'asservis � la France et priv�s de notre libert�, nous avons cess� de former une nation � part..." ou "La France, cette �trang�re qui est venue s'offrir � nos p�res un poignard � la main, et qui nous oppresse et nous tue! Non, non, � ma Bretagne...nous n'aurons de m�re que toi, nous voulons mourir sur ton sein!"

Ces d�convenues se poursuivirent jusqu'� ce que La Villemarqu� trouve dans l'historien Augustin Thierry et son ami, Claude Fauriel de l'Institut, des partisans enthousiastes de ses travaux.

Thierry ins�re en effet, en 1838, dans la 5�me �dition de son "Histoire de la conqu�te de l'Angleterre", le chant Retour d'Angleterre, en ajoutant que ce "curieux morceau de po�sie... est destin� � faire partie d'un recueil intitul� "Barzaz Breiz" dont la publication aura lieu prochainement."

Cependant, l'organisme public sollicit�, le "Comit� historique de la langue et de la litt�rature fran�aises", refusa de cautionner la publication du "Barzhaz" objectant

"l'impossibilit�...d'en constater la date, l'origine...et combien il serait f�cheux pour le Comit� de couvrir de son cr�dit la fraude de quelque McPherson inconnu." (L'auteur des po�mes d'Ossian qui avait perdu toute cr�dibilit� depuis longtemps).

Le Gwenc'hlan gallois de La Villemarqu�

Le 30 avril 1838 La Villemarqu� �tait missionn� par le Minist�re de l'Instruction publique pour participer en octobre au congr�s celtique dit "Eisteddfod" d'Abergavenny au Pays de Galles. La perception qu'il eut d�sormais du myst�rieux proph�te se ressentit, tout comme l'ensemble de son �uvre, de ce contact prolong� avec la culture cambrienne (cf. encart ci-apr�s). - Dans l'introduction au Barzhaz de 1839, il expose ce qui suit (pp. xi-xv):"De m�me que les habitants du pays de Galles avaient recueilli les �uvres de leurs po�tes les plus c�l�bres, les Bretons d'Armorique ont poss�d� jusqu'� la fin du dernier si�cle un recueil des chants d'un de leurs bardes...[Il] se nommait Gwenc'hlan et ses po�sies [ont �t�] confondues, mal � propos, avec le manuscrit breton de Sainte-Nonn...Suivent les �lucubrations de Miorcec sur la renomm�e future que le proph�te se pr�dit et sur la vindicte dont il accable les pr�tres chr�tiens.

- Mais, fait nouveau, il affirme qu'il faut voir dans le nom de Gwenc'hlan ('race pure' et non 'chien malade') le surnom d'un certain "Kian qu'on appelle Gueinchguant" (Cian qui vocatur Gueinchguant), cit� par Nennius, historien britannique du 9�me si�cle �crivant en latin. S'il s'agit vraiment de lui, l'�tymologie de Miorcec est moins fausse que celle de la Villemarqu�: Ce m�me Kian est �voqu� dans le po�me "Y Gododdin", tir� du "Livre d'Aneurin" datant de la fin du 13�me si�cle et racontant une bataille qui eut lieu au 6�me si�cle. Il y est question de "Cian o vaen Gwyngwn" que l'on traduit par "Kian de la Roche aux Chiens Blancs", o� Cian signifie "Petit chien" et ses fils sont nomm�s "aer gwn" -chiens de guerre et non "blanc sommet", comme l'affirme La Villemarqu�!

A titre de justification, il indique que des �crivains anglais modernes, l'historien Sharon Turner et Evan Evans, le traducteur de "Y Gododdin" admettent de telles approximations pour les po�tes gallois Aneurin et Llyfarc'h Hen!

Signalons que dans un article publi� dans les "Annales de Bretagne", 1930, vol. 39-1, page 30, Emile Ernault rapproche ce nom de "Gwengolo" (Paille Blanche) qui d�signe le mois de Septembre.

La plus r�cente remarque que j'aie trouv�e � ce sujet explique "Gueinth Guant" par "Gwenith Gwawd" qui signifierait "Froment (breton "gwinizh") de Louange". - Si le jeune homme s'est effectivement r�f�r� � des chants entendus � Nizon, on peut penser qu'il s'est inspir� pour les "mettre au point" des mod�les gallois qu'il signale lui-m�me d�s l'�dition de 1839 avec une franchise d�sarmante et qui sont presque tous tir�s de l'incontournable collection de Myvyr. Certaines de ces r�f�rences sont appuy�es de citations dans un gallois (?) qui ressemble au breton dans l'orthographe de Le Gonidec. Ces curieuses traductions dispara�tront de l'�dition 1867:

- Tali�sin qui croit � la m�tempsychose: "Je suis n� deux fois...j'ai �t� mort, j'ai �t� vivant; je suis tel que j'�tais... J''ai �t� biche sur la montagne... J'ai �t� un coq tachet�...J'ai �t� daim de couleur fauve; maintenant je suis Tali�sin" (cf. strophe 9).

Le m�me Tali�sin, en parlant d'un chef gallois, l'appelle le "cheval de guerre" (str. 13). - Llyfarc'h Hen le fataliste: �Si ma destin�e avait �t� d��tre heureux, [toi mon fils] tu aurais �chapp� � la mort... Avant que je marchasse � l�aide de b�quilles, j��tais beau... je suis vieux, je suis seul, je suis d�cr�pit... Malheureuse destin�e qui a �t� inflig�e � Llyfarc�h, la nuit de sa naissance : de longues peines sans fin" (str. 2).

- Aneurin, auteur du po�me "Y Gododdin", qui fut fait prisonnier � la bataille de Catraeth: � Dans ma maison de terre, malgr� la cha�ne de fer qui lie mes deux genoux, moi, Aneurin, je chanterai, dit-il, le chant des "Gododdin" avant le lever de l�aurore.� (str. 1)

et le m�me po�me offre un vers qui se retrouve presque litt�ralement dans le chant armoricain : �On voit une mare de sang monter jusqu�au genou." (str.20) - Llyfarc'h Hen encore "quand il d�crit les suites d'un combat": � J�entends cette nuit les aigles d�Eli... Ils sont ensanglant�s ; ils sont dans le bois... Les aigles de Pengwern appellent au loin cette nuit on les voit dans le sang humain.� (str. 23 � 25)

Une tradition apocryphe?

Il est peu probable que le jeune La Villemarqu� ait cr�� ex nihilo un texte d'une telle puissance �vocatrice. - On apprend dans l'introduction au Barzhaz de 1839, que J.M. de Penguern a �galement fait des recherches sur Guinclan et qu'elles ont �t� couronn�es de succ�s. Le chant d�couvert par de Penguern ne peut �tre que "An den kozh dall" (Le vieillard aveugle). La citation qu'il en fait dans les �ditions ult�rieures:

"Mon fils vois-tu verdir le tr�fle? -Je ne vois que la digitale fleurir, r�pond l'enfant. -Alors, allons plus loin,"

permet � Villemarqu� de pr�senter son h�ros comme ayant un double aspect: barde guerrier et agriculteur.

Cette assimilation lui a sans doute �t� inspir�e par ce qu'il affirme, � tort, �tre une autre citation de Dom Le Pelletier (mais qu'il a trouv�e chez Kerdanet):

| Abarzh ma vezo fin ar bed;Falla� douar ar gwella� ed. | Que sorte avant la fin du monde Le meilleur bl� d'un sol immonde. |

| ----------------------------------------------------- | ------------------------------------------------------------------- | - Quant aux propres recherches de La Villemarqu�, elles ont abouti � la d�couverte du texte ci-dessus issu de la "tradition actuelle", que les paysans intitulent "Pr�diction de Gwenc'hlan" et qui offre "tous les caract�res de la po�sie des bardes gallois des 5 et 6�me si�cles avec ... plus ... de paganisme et une haine prononc�e contre l'Eglise chr�tienne tout enti�re".

- Pierre de La Villemarqu�, le fils du Barde, publia en 1908 une lettre que lui avait envoy�e sa cousine Camille o� il est question de Marie-Jeanne Penquerh, n�e Droal de Penanros en Nizon (1806 - 1892), cit�e sur les listes de chanteurs dress�es par la dame de Nizon. Alors que cette derni�re attribue ce chant � Anna�k Huon, �pouse Le Breton, de Kerazul en Nizon, Camille affirme que Marie Penquerh se souvenait fort bien de quelques vieux chants rares et, parmi eux, de la "Proph�tie de Gwenc'hlan". La Villemarqu�, quant � lui, indique dans l'"argument" du chant de 1845, l'avoir recueilli "en Melgven aupr�s de Guillou Ar Gall".

Cette double source recoupe l'indication fournie par le P�re Gr�goire dans l'introduction de son Dictionnaire (Liste des auteurs dont je me suis servi pour composer ce dictionnaire):

"Guinclan...tr�s fameux encore aujourd'hui [1732] parmi les Bretons qui l'appellent commun�ment le Proph�te Guinclan". - Par ailleurs, entre l'�dition 1839 pour laquelle le jeune La Villemarqu� ne disposait que de ses propres ressources linguistiques et l'�dition suivante de 1845 qui a sans doute b�n�fici� du contr�le d'un authentique bretonnant, l'Abb� Henry, on ne note aucun changement important, si ce n'est le remplacement de "kurun"(tonnerre) par "taran" (tonnant), strophe 15.

- Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville, pourtant tr�s sceptique quant � l'origine des pi�ces historiques du Barzhaz, traite du pr�sent po�me dans son "Etude sur la 1�re et la 6�me �dition des Chants populaires de Bretagne" publi�e en 1867 dans la "Biblioth�que de l'Ecole des Chartes", tome 28, p.272, dans des termes qui montrent qu'il ne doute pas de l'authenticit� du "Gwenc'hlan". A propos de certains changements minimes op�r�s par l'auteur entre les 2 �ditions, il approuve le remplacement de "vorc'higo" (porcelets, strophe 12) et "kerno" (cornes, strophe 14) par "voc'higo�" et "kernio�", mais il critique, � la strophe 24, celui de "ezned" (oiseaux) par le moderne "evned" et, � la strophe 8, celui de "Deuz forz petra a c'hoarvezo" (il vient forc�ment ce qui arrivera), par "Na vern petra a c'hoarvezo" pour justifier la traduction fautive de 1839: "Peu importe ce qui arrivera".

Il n'est pas plus indulgent pour des modifications de d�tail introduites, tant�t pour se conformer aux r�gles de Le Gonidec: la disparition du double archa�sme "and erc'h gann" (la neige blanche, mot f�minin, strophe 14), remplac� par "an erc'h kann" (forme moderne masculine pr�c�d�e de l'article usuel); l'imparfait "me a gane" au lieu du conditionnel "me ganefe"; avec un "e" intercalaire, tant�t pour cr�er de nouvelles allit�rations: "Pa" (quand), r�p�t� 4 fois dans les stophes 1 et 2, au lieu de "Ma" (si). C'est le m�me souci de l'allit�ration qui le conduit � transformer la strophe 15:

An dour dindan hen o firvi

Gant an tan gurun euz he fri.

qui devient:

An dour dindana� o virvi�

Gant an tan daran eus e fri.

ainsi que la strophe 14:

En ken gwenn ewid an erc'h gann.

qui devient:

E� ken gwenn evel an erc'h kann,

alors que, s'il s'en �tait tenu aux r�gles �dict�es par Le Gonidec, il aurait �crit:

E� ker gwenn evit an erc'h kann,

dont toute allit�ration aurait disparu.

Jubainville n'aurait certainement pas consacr� plus de la moiti� (pr�s de 8 pages) de son �tude � un texte qu'il aurait consid�r� comme une simple forgerie � laquelle on pouvait toucher sans inconv�nient. C'est pourquoi, on ne saurait consid�rer � coup s�r ce chant comme apocryphe, m�me si, � n'en pas douter, il a �t� s�rieusement "retravaill�" par le collecteur, selon son habitude.

Le Gwenc'hlan des Romantiques - Les "notes et �claircissements" de l'�dition de 1839 du Barzhaz portent l'indication que l'attribution (dans l'argument) � Gwenc'hlan de cette pi�ce qui ne cite nulle-part son nom se justifie par la strophe 23, car le proph�te "marque au commencement de ses pr�dictions, dit le P�re Gr�goire de Rostrenen, qu'il [�crivait l'an de salut 240], demeurant entre Roc'h-Hellas et le Porz-Gwenn au dioc�se de Tr�guier, entre Morlaix et la ville de Tr�guier" (Introduction: liste des auteurs utilis�s par le P�re Gr�goire pour son dictionnaire).

En 1852 l'Abb� Daniel pla�ait Guinclan sur le rocher "o� le barde Gwenc'hlan maudit tant de fois le christianisme naissant dans nos contr�es... [On] a fait derni�rement �riger une croix sur la pointe de Roc'h Allaz: c'est encore un d�menti de plus donn� aux pr�dictions de Gwenc'hlan_" (Biblioth�que bretonne, Saint-Brieuc II, p.761). La m�me conception se retrouve sous la plume d'Anatole de Barth�l�my dans ses "M�langes historiques sur la Bretagne", I, 1853, p.58 et Benjamin Jollivet dans sa "G�ographie des C�tes-du-Nord", IV, 1859, p.123_ - Cette "tradition" en contredisait une autre, comme l'affirme R. Largilli�re dans les "Annales de Bretagne", tome 37, N�3-4, p.300, qui pla�ait � B�gard le lieu de r�sidence du proph�te et son tombeau dans l'abbaye de cette paroisse situ�e � 6 km au nord-est du M�nez-Br�. En r�alit�, cette fiction avait �t� cr��e par un auteur obscur, Poignand, dans un ouvrage intitul� "Antiquit�s historiques et monumentales de Montfort � Corseul" publi� � Rennes en 1820, au motif que B�gard et Guinclan signifieraient tous deux "bouche excellente". Ces �lucubrations ont de l'importance dans la mesure o� elles ont �t� connues: elles furent reprises par un autre auteur tout aussi obscur, Marchandy, en 1825, dans "Tristan le Voyageur".

- Quant � l'option retenue par Kerdanet qui fait du M�nez-Br� la retraite, puis le tombeau de Guinclan, c'est �galement celle de multiples auteurs: Le Maout ("Annales Armoricaines", Saint-Brieuc, 1846, p.38), Les continuateurs d'Og�e, (en 1853 au mot "P�dernec"), Pol de Courcy ("Itin�raire de Rennes � Saint-Malo", 1864, p.194), S. Ropartz ("Histoire de Guingamp",2�me �dition, I, p.15, en 1859), Geslin de Bourgogne et A. de Barth�l�my ("Anciens �v�ch�s de Bretagne", III, I, p. ix, en 1864)...

Les deux dictons "barbares"

Comme on l'a dit � propos du "Gwenc'hlan gallois", La Villemarqu� n'�tait pas en reste et citait, lui aussi, "Gwenc'hlan selon Kerdanet" d�s la premi�re �dition du Barzhaz de 1839 (pp. xi, xii et 11):

"L'avenir entendra parler de Gwenc'hlan..." et "Un jour les pr�tres chr�tiens seront traqu�s comme des b�tes fauves". - Par ailleurs, La Villemarqu� attribuait � "une tradition populaire" deux dictons barbares qui apparaissent dans l'�dition de 1845 et dont il a pu s'inspirer:

"Tud Jezus-Krist a wallgasor / Evel gouezed o argador" (Les pr�tres du Christ seront poursuivis/ On les huera comme des b�tes fauves).

Dans l'�dition de 1839, on rappelle aux lecteurs de "L'histoire de la langue des Gaulois" qu'une tradition dans ce sens est "rapport�e par M. de Kerdanet", mais cette pr�cision ne figure plus aux �ditions suivantes

et, - "Rod ar vilin a valo flour / Gand goad ar venec�h eleac�h dour." (La roue des moulins moudra menu: le sang des moines lui servira d�eau).�

On trouve un �quivalent fran�ais de cette phrase dans le "Guyonvarc'h" de Dufilhol (Paris, 1835, pp.26, 109 et 163): "Arrose, arrose ton moulin, il veut tourner avec du sang". R. Largilli�re consid�rait en 1925 qu'on avait l� un centon qui existe encore dans la bouche des paysans du Bas-Tr�guier.

L'authenticit� de cet aphorisme semble confirm�e par une communication du grammairien Fran�ois Vall�e au congr�s de Moncontour de l'"Association Bretonne", en 1912, qui affirma avoir recueilli une "proph�tie rim�e" sur la r�surrection de Guinklan, sur le combat terrible qui doit se livrer et sur "le moulin de l'�le Verte qui tournera avec du sang".

Cette affirmation est accueillie avec le plus grand scepticisme par Francis Gourvil en 1960 dans son important ouvrage d�j� cit�.

Le Gwynglaff du "Dialogue avec le roi Arthur"

En 1924, ce m�me Francis Gourvil (1889 - 1984) d�couvrit dans le grenier du manoir de Keromn�s, en Locqu�nol�, pr�s de Morlaix, � l'occasion d'un partage de biblioth�que, un manuscrit contenant 247 vers int�gralement copi�s par Dom Le Pelletier lui-m�me constituant la fameuse proph�tie, sous le titre "Dialog etre Arzur, Roe an Bretounet ha Gwynglaff" (Dialogue entre Arthur, roi des Bretons et Guinclan), suivi des mots "L'an de Notre Seigneur Mil quatre cent et cinquante".

Un copiste mal avis� avait ratur� le mot "mil" (ce qui explique l'erreur du p�re Gr�goire), mais, pour critiquer cette rature, le savant Dom Pelletier attirait l'attention sur les mots fran�ais dont ce texte est truff�, au nombre desquels on trouve "canol" pour "canons".

Le texte de ce "Dialogue" o� Guiclan ne figure pas comme auteur, mais comme acteur, est structur� comme suit, selon l'analyse publi�e par R. Largilli�re dans les "Annales de Bretagne" (tome 38, 1929):

1� Vie de Gwynglaff, �tre � demi sauvage, n'ayant d'autre abri que les arbres des for�ts dans lesquelles il errait couvert d'une cape rousse. Il connaissait l'avenir. (c'est le th�me de l'"homme sauvage" que l'on retrouve dans le chant Merlin Barde).

2� Un dimanche, le roi Arthur [une r�f�rence antique qui, elle aussi, excuse Gr�goire de Rostrenen] se saisit de lui et lui intime l'ordre assorti de menaces de lui dire quels prodiges arriveront en Bretagne avant la fin du monde.

3�R�ponse: "Tu sauras tout, except� ta mort et la mienne" suivie de pr�cisions difficiles � interpr�ter; �t� et hiver confondus, jeunes gens � cheveux gris, la pire terre qui fournit le meilleur bl� [ce qui confirme l'affirmation de La Villemarqu�]; h�r�tiques d�fiant la loi divine, etc.

4� Pr�dictions concernant les ann�es de 1570 � 1575 et 1587 et 1588.

5� Longue r�ponse � une question du roi: guerres et destructions imputables aux seuls Anglais. Sous peine d'�tre d�capit�s, les Bretons sans armes et les gens arm�s devront affronter les ennemis. Ils mourront par bandes et par troupes sur le M�nez Br�; devront assi�ger Guingamp, rompre ses murailles et piller ses biens. On violera les filles, tuera hommes et femmes. Par punition de Dieu, les Saxons prendront possession de la Bretagne.

Les passages en caract�res gras avaient �t� cit�s par divers auteurs avant la red�couverte du manuscrit. D'autres sont cit�s dans les deux dictionnaires qui s'en inspirent, mais sont absents du manuscrit: le mot "orzail" (Le Pelletier) et la phrase indiquant que Guinclan "demeurait entre Roc'h-Hellas et le Porz-Gwenn" (Gr�goire). Sur le manuscrit, Dom Le Pelletier mentionne 2 versions des Proph�ties. Ces mots doivent figurer sur la version manquante qu'il a montr�e au P�re Gr�goire.

Selon J. Tourneur-Aumont, dans les m�mes Annales, il s'agit d'un "Chant royal" compos� suivant les canons en vigueur au XV�me si�cle pour servir les int�r�ts du roi de France Charles VII. L'int�r�t de ce texte est philologique, non historique. F. Gourvil remarque que rien n'indique qu'il ait �t� la propri�t� de l'abbaye de Land�vennec et rien n'autorise non plus � supposer qu'il ait �t� d�truit sous la R�volution.

Dans le "Que-sais-je?" qu'il consacre en 1952 � la "Langue et litt�rature bretonnes", le m�me Francis Gourvil souligne insidieusement, que, selon lui, cette d�couverte "a permis de r�duire � n�ant les pr�tentions de ceux qui, croyant le texte disparu � jamais, avaient inconsid�r�ment abus� de lui." Il est clair qu'il vise sp�cialement le po�me publi� par La Villemarqu�.

Il ressort, cependant, de ce qui pr�c�de, que ce dernier ne pr�tendait nullement avoir restitu� les "proph�ties" disparues, mais rendre compte d'une tradition orale.

Loin d'infirmer les affirmations du jeune Barde, cette pi�ce les confirme: - Elle reprend deux de ses citations: "Les pires terres..." et "Ils mourront sur le M�nez-Br�..."; (Cette seconde citation se trouve page 65 du 3�me carnet de collecte de LaVillemarqu� publi� en novembre 2018, suivie de la phrase 'Savan ma mouez war ar Menez-Bre"= "J'�l�ve ma voix sur le M�nez-Br�"). Ce passage conclut une description de cette colline, de la chapelle qui la surmonte, du menhir taill� en croix, de la foire qui s'y tient le 17 juin, f�te de Saint Herv�. Il est orn� de dessins: la croix-menhir, une porte et des armoiries portant hermines, cloches et anneaux.

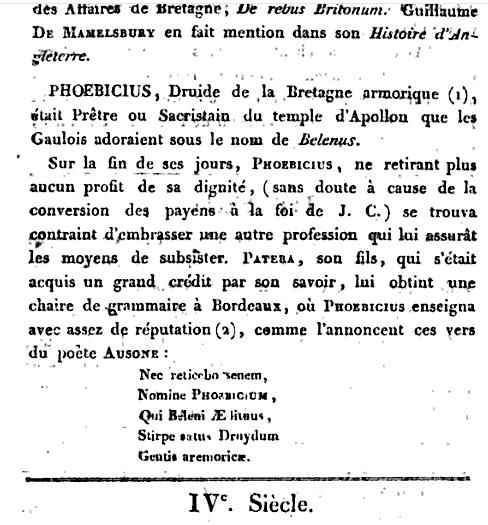

La Chapelle Saint- Herv� aujourd'hui (Photos J. Philippe-Quentin) - Elle fait de Gwynglaff un contemporain du roi Arthur, autre personnage l�gendaire dont Nennius dans son "Historia Brittonum" (ca 960) dit qu'il livra diverses batailles contre les Saxons dont celle de Mont-Badon qu'un autre document r�dig� � la m�me �poque, les "Annales Cambriae", date de 516. Si Gwenc'hlan avait v�cu, ce serait donc au VI�me si�cle.

Le Gwenc'hlan d'Anatole Le Braz

On a vu � propos des S�ries que La Villemarqu� avait en Anatole le Braz un critique acerbe. Et pourtant, dans les "Contes du Soleil et de la Brume" (1905) du m�me Le Braz, on trouve une description tr�s po�tique du M�nez-Br�, cette "montagne" de 300 m � l'ouest de Guingamp, dont il assure que:

"Les Bretons du VI�me si�cle n'h�sit�rent pas � lui confier l'ombre de leur fameux Gwenc'hlan dont le souvenir et les chants les avaient accompagn�s dans leur exode. Barde et proph�te, comme Merlin, Gwenc'hlan, dont le nom veut dire "race sainte", passait pour avoir �t� l'un de ses plus brillants continuateurs."

Le Braz ne rechigne pas � citer les trois premi�res strophes du Barzhaz, lorsqu'il �voque "la plainte am�re que lui a pr�t�e, dans le Barzaz-Breiz, le vicomte de La Villemarqu�."Il poursuit:

"Dans toute l'ancienne Domnon�e [c�te nord de la Bretagne], ses pr�dictions �taient c�l�bres. Elles furent m�me r�dig�es par �crit et l'on en conservait, para�t-il, un recueil, il y a quelque deux cents ans, chez les moines de Land�vennec. Aujourd'hui, ce n'est gu�re que dans la m�moire du peuple que l'on peut trouver un �cho fort affaibli de ces paroles sibyllines, de ces 'diou-gano�'".

La source de cette tradition orale relative au proph�te n'est autre que Marguerite Philippe, ou Marc'harid Fulup, (1837 -1909). Aussi appel�e Godik ar Vognez (Margot la Manchote), c'�tait l'informatrice principale de Luzel, � Plouaret et elle lui enseigna � elle-seule 259 chants. En l'occurrence, il s'agit de contes relatifs au myst�rieux personnage: - Il habitait le manoir de Run-ar-Goff � l'ouest de la montagne et pouvait tourner compl�tement la t�te vers l'arri�re � la mani�re des chouettes.

- Il voyait les �v�nements se mettre en marche, mais il parlait peu, pr�f�rant converser avec les corbeaux et les oiseaux migrateurs qui l'informaient des �v�nements du monde.

- Une fois il combattit toute une journ�e un ennemi invisible avec son �p�e, au sommet du M�nez-Br�. Il avait extermin� de futurs envahisseurs et les nuages �taient rougis de leur sang.

- Avec la plume d'un "aigle de mer" il �crivit son testament: il poss�dait des richesses immenses qu'il garderait, avec ses livres et ses secrets, dans une s�pulture inconnue. Quant aux Bretons, qu'ils gardent leur pauvret�, car elle est la source des meilleures joies. Les douze chariots charg�s de son or, conduits des hommes aux yeux band�s, firent plusieurs fois le tour de la montagne avant de d�verser leur contenu dans un puits sans fond. Puis on entendit un grand soupir. C'est tout ce qu'on savait de la fin de Gwenc'hlan.

- "Tous les cent ans, dit-on, la nuit de la premi�re lune, le M�nez-Br� s'ouvre...Si quelqu'un...se risquait dans la fente, une lumi�re magique s'�l�verait devant lui pour le guider jusqu'� Gwenc'hlan... [dont] l'esprit remplit les entrailles de la montagne comme la vertu de Saint-Herv� en parfume le sommet" (le M�nez-Br� est couronn� d'une chapelle d�di�e � ce saint: un thaumaturge en chasse un autre).

Une tradition similaire est �voqu�e par M. Le Teurs dans le "Bulletin de la Soci�t� Arch�ologique du Finist�re" (1875-1876, p.179). Elle concerne la paroisse de Saint-Urbain dans le Finist�re, o� un tertre nomm� "Torgen ar Sal" est r�put� �tre la s�pulture de "Gouincl�". Il y repose avec ses tr�sors.

L'interpr�te habituel de Marguerite Philippe, Fran�ois-Marie Luzel n'a jamais entendu parler de Gwenc'hlan, si ce n'est, dit-il, qu':

"A Louargat, au pied du M�nez-Br�, une vieille femme que j'interrogeais m'a dit un jour qu'il y avait autrefois ur Warc'hlan sur le sommet de la montagne. Serait-ce une alt�ration de Gwinglaff? Elle ne savait du reste si c'�tait un homme ou un animal".

La conclusion que tire R. Largilli�re de ce qui pr�c�de dans son �tude sur Gwenc'hlan, c'est que

"

les cr�ations litt�raires des �crivains du XIX�me si�cle ont p�n�tr� dans le peuple"

et que, loin de rapporter fid�lement, comme il l'affirme, les paroles de Marguerite Philippe, Anatole Le Braz a beaucoup enjoliv� son r�cit. C'est d'autant plus probable, selon lui, que dans un article de "La Plume" du 1er mars 1894, il �crivait:

"Qui de nous n'e�t aim� � se repr�senter comme r�el ce grand spectre bardique...sur la cime solitaire du M�nez-Br�? [comme l'a fait La Villemarqu�] ...Mais la critique s�rieuse en doit faire son deuil. Je ne m'y r�signe pas sans regret".

Le Braz aurait-il, onze ans plus tard, succomb� au mirage et commis envers la muse populaire les m�mes ind�licatesses que celles qu'il se plait � reprocher � La Villemarqu�? On peut en douter.

Le Barzhaz Breizh: un mauvais livre?

En 1960, F. Gourvil devient plus cat�gorique et soutient une th�se � l'universit� de Rennes, publi�e plus tard sous le titre r�v�lateur: "L'authenticit� du Barzaz Breiz et ses d�fenseurs � la rescousse d'un mauvais livre". Puis en 1966, il critique, de fa�on peut-�tre plus justifi�e, "La langue du Barzaz Breiz et ses irr�gularit�s".

Ces positions excessives sont largement infirm�es par les travaux de M. Donatien Laurent. Ce musicien et linguiste d�couvrit en 1964 au manoir de Keransquer, pr�s de Quimperl�, propri�t� de la famille de La Villemarqu�, les carnets de collecte de ce dernier. - Ils montrent que Kervarker connaissait correctement le breton.

- Ils montrent aussi que, s'il a pris, au regard de r�gles �tablies ult�rieurement, de trop grandes libert�s avec les textes recueillis, il n'en reste pas moins que bon nombre de chants consid�r�s par F. Gourvil (et Le Men, Luzel, F. Lot, d'Arbois de Jubainville, A. Le Braz, etc.) comme des inventions s'av�rent comme ayant �t� bel et bien collect�s.

Conclusion

Il doit en �tre de cette "diougan" (proph�tie) comme des autres chants mythologiques et historiques anciens du Barzhaz. Elle unit � une magnifique m�lodie authentique, des mots,

"peut-�tre des fragments de vers ench�ss�s dans un r�cit en prose" (comme l'�crit Donatien Laurent), r�ellement collect�s � Melgven par l'auteur (ou sa m�re), mais dont certains �l�ments sont compl�tement transfigur�s, comme ce devait �tre le cas, dans l'�dition de 1845, pour les "V�pres des Grenouilles."

La source du chant dont se souvenait Cl�mence Penquerc'h �tait-elle le Barzhaz-Breizh lui-m�me? De l'avis de Donatien Laurent,:

"[On] admettra difficilement qu'un chanteur illettr� et monolingue retienne justement du recueil cette pi�ce marginale si diff�rente de ton et d'inspiration de celles de son r�pertoire habituel [et que, de plus,] la Dame de Nizon, elle aussi, mentionne" (comme chant�e par Anna�k Le Breton).

En tout �tat de cause, on ne peut que regretter, comme le fait Donatien Laurent, que personne ne soit " all� voir Cl�mence Penquerc'h, fille de la Marie-Jeanne des tables qui n'est morte qu'en 1908!"

M�me si la "Proph�tie de Gwenc'hlan" est en partie une �uvre autonome, cr��e par La Villemarqu�, en faisant appel � des souvenirs livresques, pour les besoins de ses diverses causes, on ne peut qu'admirer l'extraordinaire force d'�vocation po�tique de cette pi�ce.

Les qualit�s de ces textes "d'imagination" sont pour beaucoup dans l'engouement suscit� par le "Barzhaz Breizh" dans toute l'Europe: on trouvera ici une paraphrase de la "Marche d'Arthur" et la traduction du d�but de la "Proph�tie de Gwenc'hlan" publi�e en 1912 en NEERLANDAIS.

Note: Outre "Aux Sources" de Donatien Laurent, une grande partie des d�veloppements ci-dessus est tir�e de l'ouvrage de Francis Gourvil, "Th�odore de La Villemarqu� et le Barzaz-Breiz" (1960) qui n'est autre que sa th�se de doctorat.

L'autre source principale est l'article "Gwenc'hlan" publi� par R. Largilli�re in: "Annales de Bretagne, Tome 37, num�ros 3-4, 1925. pp. 288-308.

R�sum� It was with this song that the first 1839 edition of the Barzhaz opened, before it was "superseded" by the "Series" in 1845 . Gwenc'hlan is a bard whom a Christian prince held captive after he had gouged out his eyes. Having a gift for prophecy, he predicts that he will be avenged by a Pagan prince. He has a vision: a wounded boar (the Christian prince) accompanied by its young which a white sea horse (the Pagan prince) furiously hits with its silver horns, shedding a pool of blood. Another vision: the bard lies in his grave. He hears the eagle calling its eaglets and all the birds of the sky that they may feed on Christian flesh. A raven is endeavouring to peck out the two red eyes off the head of the Christian chieftain who had imprisoned the bard and gouged out his eyes. A fox tears his hypocrite heart to pieces. As for his soul, it is doomed to don the body of a toad.

Unlike the previous piece, this poem never was collected by anybody but La Villemarqu�. Most folklorists, especially Francis Gourvil who discovered in 1924 a "Chant Royal" whose existence was stated by two 18th century authors, look on the Barzhaz ballad "Gwenc'hlan" as on a forgery composed by the young scholar in combining bookish reminiscences, in particular Welsh Bardic poetry. These Wesh poems became his favourite references as a consequence of his partaking in the 1838 "eisteddfod" at Abergavenny. But anyone pondering on this "Chant Royal", on the Barzhaz poem and the comments accompanying it, on a letter penned by the Bard of Nizon's niece, Camille de La Villemarqu�, as well as an essay by one of his usual disparagers, Anatole Le Braz, will be led to reconsider their opinion and to admit that, even if it is missing in the Keransquer MSs, genuine lore possibly, if not very likely existed whereon this inspiring epic poem is based.

The Guinclan of the dictionaries In 1834 many Breton scholars were in search of a mysterious MS: "Guinclan's prophecies" (or "Guiclan" or "Guinclaff") which was considered lost when the Benedictine abbey of Land�vennec was destroyed by the Revolution. Now it was formerly kept there, according to two linguists, the Reverend Le Pelletier and the Capucin monk Gregory of Rostrenen. Both of them had composed Breton dictionaries where they respectively quoted excerpts from this document, or mentioned its existence.

- Dom Le Pelletier (1663 - 1733) compiled a "Dictionary of the Breton language" which was published after his death, in 1752. In this book he asserts that he had at his disposal, at Land�vennec Abbey, this manuscript where he found words for his dictionary (he was born in Le Mans and was no native Breton-speaker). The Reverend Taillandier who wrote the preface to the posthumous work stated on page VIII that

"the oldest monument in Breton language found by the Reverend Pelletier was a MS dating from the year 1450, namely a collection of prophecies by an alleged seer named Gwinglaff. He also availed himself, to a slight extent, of the Life of Saint Gu�nol�, the first Abbot of Land�vennec".

Gwinglaff is really quoted three times in this dictionary:

- under the items "bagad" ("party"),

The plural is 'bagadou' which translates 'lots of people' in Gwingl�f's Prophecies that announce:Ma'z marvint oll a strollado�,War Menez-Br�, a bagado�. That they will die, the lot of them,On the M�nez Br�, whole legions. - "gnou" (public knowledge) - and "orzail", (="battery", a corrupted word derived, so says Le Pelletier from the French "assaillir"). - Even before this work was published, another divine, the Capucin Gregory of Rostrenen (1667 -1750) released his own "Celto-Breton Dictionary", in 1732, where he quoted the said Guinclan:

1� In the Introduction: List of authors used to compose this dictionary:

"The oldest document in Breton language I found was the hand-written Breton Predictions of Guinclan, a Breton astronomer who is still very famous among today's Bretons who usually refer to him as 'Prophet Guinclan'. He states at the beginning of his Predictions that he wrote in the year of grace two hundred forty (240), when he was dwelling between Roc'h-Hellas and Porz-Gwenn, in the bishopric Tr�guier, between Morlaix and Tr�guier town".

2� Under the item "Guinclan", on page 480 of the dictionary that includes several proper nouns:

"Guinclan a Breton prophet or, more precisely, an astronomer who lived in the third century, whose predictions in Breton verse I saw, at Land�vennec Abbey, in the hands of the Reverend Dom Louis Le Pelletier."

Apparently, he did not peruse it intently, since he added:

"He was born in the County Go�lo [the area between Paimpol and Saint Brieuc], and had foretold around the year of grace 240 (as he asserts himself) whatever was to change and to happen since then in "both Brittanies" [i.e. Brittany and Britain, as stated in the Breton version of his note]."

He must have been aware of the contradiction with Dom Pelletier's future dictionary, since, 6 years later, he partly corrected this statement in his "Celto-Breton Grammar" (1738):

"A gross mistake has crept into my Dictionary, concerning Guinclan whose "Predictions" I have dated to the year 240, instead of the year 450".

3� For the sake of exhaustiveness be it said that the item "prediction", on page 479, includes the prompt (See G�inclan). The latter item contains the same translation for "prediction", namely "diougan". - There was still a difference of a thousand years! Yet the scholars interested in Guinclan would always mention this latter date: "the year 450". So did Cambry in his "Trip through the Finist�re" (1797), as well as the Abb� de la Rue in his "Enquiries about the Bards" (1815).

Miorcec de Kerdanet's Guinclan

So did above all the local historian Daniel-Louis Miorcec de Kerdanet in his "Chronological notices" (1818) where he writes on pages 8-9: - "[Guinclan] foretold around the year 450 upheavals and transformations in Britain and Brittany and the fame he was to enjoy among the posterity." The future shall hear of Guinclan. Some day the offspring of Brutus shall be loud on the M�nez-Br� Mount and they shall cry, looking at the Mount: 'Here was Guinclan's dwelling'; and they shall consider the generations that no longer live and the times to come, that I was able to fathom."

La Villemarqu� quoted this sentence, on trust in the "Bibliographie bretonne" edited by Levot (1852). It is easy to prove that this is a mere paraphrase of "The Carros War", which is part of a translation by Le Tourneur of McPherson's "Ossian, son of Fingal":

"Times to come shall hear of Ossian. Some day the Coward's offspring shall raise their voices on the hills of Cona. And they shall cry, looking at these rocks: 'Here was once Ossian's dwelling'; and they shall marvel at the folks of yore and the heroes I celebrated." - Miorcec adds:

Guinclan had predicted the plague that harried Guingamp and its surroundings in 1486:

"Ma'z marvint holl a strollado�

War Menez Br�, a bagado�."

meaning:

"That they will die, the lot of them,

On the M�nez Br�, whole legions."

This quotation will be found under the word "bagad" in Le Pelletier's dictionary, page 33, with the bare mention that the plural "bagado�" meaning "legions" occurs in "Gwinl�f's Prophecies".

These "Prophecies", rediscovered in 1924, really address above all the future of Guingamp between 1570 and 1588. But in this document, the human flocks that will be slaughtered upon the M�nez-Br� (20 km west of Guingamp) are Bretons who were forcibly enlisted by the English. La Villemarqu� will quote the same sentence but consider it applies to the priests of Christ. - Guinclan is invoked again by Miorcec in his "History of the Gauls' language", in 1821, on pp.33-34:

"In 450 "Gwinclan's Prophecies" in Breton were published. He was a bard and seer from the Tr�guier shire. His resentment against the Christian priests earned him the nickname "Guinclanff" or "Quinclanff", i.e. "rabid dog". He assured that, in times to come, the ministers of our holy faith would be hunted down like wild beasts. It was as if he foretold the troubles of the French Revolution." - Kerdanet "recycled" these diverse features in his edition of the "Lives of the Saints of Brittany", by Albert Le Grand, published in Brest in 1837. He "translated" into Breton the famous phrase about the generations that no longer live and the times to come, that the prophet was able to fathom":

"An amzerio� tremenet

Hag an dud diskilhet..." - He added that his hero gave orders to be buried under the M�nez-Br�, but forbade, as did Nostradamus, that his grave be ever opened or else this violation would cause a lot of upheaval in the whole universe.

- He also ascribed to Gwinclan a prediction to the effect that those who clear the worst soils for cultivation shall garner the best wheat. As we shall see, this prediction found its way into the Barzhaz, as well. Much more astonishing is that it will be found in the "Dialogue" discovered in 1924:

| Abarzh ma vezo fin ar bed;Falla� douar ar gwella� ed. | Before Doomsday shall be yieldedBy the worst soil the best wheat.. |

| ----------------------------------------------------- | -------------------------------------------------------------------- |

Much more than Father Gregory and his erroneous dating, it was, consequently, Miorcec de Kerdanet who was accountable for the wild imaginings that throve about the famous prophet of the fifth century. They inspired in particular young La Villemarqu�.

An alleged discovery by La Villemarqu�

As mentioned on the page dedicated to the first song he ever published "The Plague in Elliant", the young scholar had in 1835 an interview with Miorcec at the latter's house in Lesneven. The both certainly evoked in their discussion the ghostly prophet, since La Villemarqu� asked in a post-scriptum to the letter he sent to his friend on 20th September:

"Do you have the Guinclan MS now? How old is this unique document?"

- Now, at about the same time, the General Inspector of Historical Monuments, Prosper M�rim�e (the author of the famous novel "Carmen", as well as the literary forgery "Theatre of Clara Gazul") was instructed by the Ministry of Education to enquire about the existence of the famous MS in the public libraries of Brittany and to negotiate its acquisition. He was informed on 15th or 16th September by one of his friends, Count de Carn�, upon his arrival in Quimper, that the MS was already discovered, not by Miorcec, but by La Villemarqu�. The Inspector was seemingly pleased to hear it and, on 17th September, continued on his travel south-eastwards.

- Unfortunately, a month later, the Nantes Legitimist paper "The Stoat" that had published the false news of the discovery on 16th October 1835, (which was forwarded by two big Parisian dailies, "Courrier Fran�ais" and "Journal des D�bats" on 28th and 29th October who even copied the misspelt proper nouns: "Delaville-Marqu�" and "Quin-Clan"), informed their readers on 30th October of a new incident: when young La Villemarqu�, duly authorized by the bishop of Quimper, came to copy the MS on the spot, they told him that the precious paper had already been taken away by M. M�rim�e himself. The opposition to the government, especially the journal "La Mode" seized this opportunity to revile the Guizot Ministry.

Francis Gourvil who recounts these proceedings in his stately book on "La Villemarqu� and the Barzaz-Breiz", published in 1960, considers the silence of the young man on that occasion as a proof of his precocious malice... - Apparently this false information arose from a mistake:

In a letter dated to the first semester 1835, Mme de La Villemarqu� wrote to her son: "I spoke with the curate of Dirinon. Several people contributed money to retrieve Guinclan".

Answer of the curate in January 1836:

"...Never did our fabric have the famous document in their possession and all that was poured forth by newspapers about it is false... They have mistaken the "Life of Saint Nonn", the patron saint of our parish, for the works of your fellow countryman... (The "Life of Saint Nonn", "Buhez Santez Nonn" was published in 1837 by the Reverend Sionnet along with a translation by the Grammarian Le Gonidec. Both letters are quoted by F. Gourvil in "Nouvelle Revue de Bretagne", issues of May and July 1949)).

The argument with M�rim�e

An interview between the two men in January 1836 apparently put an end to the controversy. But it is likely that M�rim�e's outspokenness did not fail to deeply hurt the young Breton's self-esteem and national pride. M�rim�e avenged himself by blaming the Bretons, in a report titled "Account of a trip to Western France", for neglecting the upkeep of their heritage and he urged the government to preach by example.

This argument, not only exacerbated the young man's regional jingoism, but greatly harmed his career at its very outset, as it biased against him some renowned writers like Sainte-Beuve who was the first author questioning "the accuracy... of his research methods... and wondering if he applied a critical mind to them", and Lamartine who favoured him with but non-committal encouragements.

Since the already famous "Revue des Deux Mondes" (created in 1830) had refused it, it was in the "Echo de la Jeune -France" that, on 16th March 1836, his article titled Bardic Remains was published, to which the ballad The Plague of Elliant, dating back, in his opinion, to the 6th century A.C. was attached.

It is an answer to M�rim�e's verbal brutality. "It contains in embryo the whole Barzhaz Breizh" as Francis Gourvil rightly remarked.

One may find in it flights of lyrical poetry like:

"Today we are tied to France with abject bonds and deprived of the ancient liberties we used to enjoy as an independent nation..." or "France, this alien who imposed herself on our forefathers by wielding her dagger, and is still oppressing us and killing our children! No, no, O Brittany...we shall have no mother but you and die while protecting your breast!"

These disappointments went on until La Villemarqu� found in the historian Augustin Thierry and his friend Claude Fauriel of the Institute (the 5 French Academies) enthusiastic supporters of his works.

Thierry inserted, in 1838, into the 5th edition of his "History of the conquest of England", the song Back from England, and he adds that "this curious relic of poetry... is intended to be included in a a collection titled "Barzaz Breiz" to be published very soon."

However, the public body approached, the "Historical Committee on French language and literature", refused to sponsor the publishing of the book, objecting that

"it was impossible... to trace the date and origin of the songs... and that it would not be convenient for the Committee to cover with their authority the forgery of a new McPherson."

(McPherson, the author of "Ossian" had not yet, like now, partly recovered his long lost credibility).

La Villemarqu�'s Welsh Gwenc'hlan

On 30th April 1838, La Villemarqu� was chosen by the Ministry of Education to take part in a Celtic congress, the so-called "Eisteddfod" of Abergavenny (Wales). His perception of the mysterious prophet was thoroughly influenced, as well as the whole of his work, by this prolonged contact with the Welsh culture (See insert below) - In the Introduction to the first 1839 edition of the Barzhaz he explains (pp. xi-xv): "Not differently from the inhabitants of Wales who had preserved the works of their most famous poets, the Bretons of Armorica have kept until the century past the collection of the songs composed by one of their bards...[His] name was Gwenc'hlan and his poetry [was] mistaken very unfortunately with the Breton MS about the Life of Saint Nonn... This text is followed by Miorcec's wild imaginings on the future glory the prophet forebodes for himself and the abuse he showers on Christian clerics.

- But La Villemarqu� has a new idea of his own: he asserts that Guinclan whom he names in his book "Gwenc'hlan" (="Pure Race" not "Rabid Dog"!) is identical with the named "Kian alias Gueinchguant" (Cian qui vocatur Gueinchguant), quoted by Nennius, a 9th century British historian who wrote in Latin. If this is true, the etymology imagined by Miorcec is less whimsical than that of his disciple. The same "Kian" is mentioned in the poem "Y Gododdin" which is part of the "Book of Aneurin" dating from the end of the 13th century and reporting a battle that was fought in the 6th century. He is named "Cian o vaen Gwyngwn" which may translate as "Kian of the stone of the white dogs", whereby "Kian" could mean "little dog" while his sons are named "aer gwn", "war hounds" and not "white summit", as stated by La Villemarqu�!

By way of justification he invokes the modern English authors, the historian Sharon Turner and Evan Evans, the translator of "Y Gododdin", who indulge in such assimilations concerning the Welsh poets Aneurin and Llyfarch Hen!

Another interpretation is given in a study published in "Annales de Bretagne", 1930, vol. 39-1, page 30, by Emile Ernault who parallels this name with "Gwengolo" (White straw), which applies to the month September.

The most recent relevant note I found explains "Gueinth Guant" as "Gwenith Gwawd" which would mean "Wheat (Breton "gwinizh") of Praise". - If the young man elaborated on songs he really heard at his parents' manor in Nizon, to "improve" them he possibly availed himself of Welsh models that he points out with disarming candour, most of which he found in the inevitable Myvyrian Archaeology. Several quotations are illustrated by the original Welsh (?) transcribed in Le Gonidec's Breton spelling.

These strange translations have disappeared in the 1867 edition. - Taliesin believes in metempsychosis: "I was born twice... I was dead: I am alive: I am such as I was... I was a doe upon the hill... I was a speckled rooster...I was a fawn-coloured deer.

Now I am Taliesin" (see stanza 9).

The same Taliesin, referring to a Welsh chieftain calls him "war steed" (st. 13). - Llyfarch Hen, the fatalist: "If I had been doomed to be happy, [you, my son,] would be still alive... Before I had to be on crutches, I was handsome...I am old and alone, I am decrepit... An unfortunate fate was inflicted on Llyfarch the night he was born: long, endless exertions" (stanza 2).

- Aneurin, who wrote the poem "Y Gododdin" and was taken prisoner at the battle of Catraeth: "In this clay house of mine, in spite of the shackles my knees are chained up in, I, Aneurin, shall sing, before the sun rises, the song of Gododdin" (Stanza 1)

and the same poem has a verse that appears almost unchanged in the Breton song: "There will be a spate of blood, a flood wherein we shall stand knee-deep" (st. 20). - Llyfarch again "who depicts the aftermath of a fight": "Tonight I hear the eagles of Eli... They are stained with blood... They are in the wood...The eagles of Pengwern call afar. Tonight we shall see them bathing in human blood." (stanzas 23 to 25).

Is this spurious folk lore?

One may maintain that such inspiring lyrics are unlikely to have been created ex nihilo by young La Villemarqu�. - The introduction to the song mentions, as from 1839, that J-M. de Penguern also made enquiries about Guinclan and his endeavours were rewarded. The song discovered by de Penguern may be no other than "An den kozh dall" (The blind old man). The quotation thereof made by La Villemarqu� in the ensuing editions:

"My son, do you see the clover turning green? -Nothing but digitalis turning blue, says the child. -Then let's go our way,"

enables him to make of his hero both a bard-warrior and a soil tiller.

Maybe he was prompted to this assimilation by an alleged quotation of Dom Pelletier (which he found in one of Kerdanet's books):

| Abarzh ma vezo fin ar bed;Falla� douar ar gwella� ed. | Before Doomsday shall be yieldedBy the worst soil the best wheat.. |

| ----------------------------------------------------- | -------------------------------------------------------------------- | - As for La Villemarqu�'s own enquiries, they have led to the discovery of the song above pertaining to "oral tradition".

Country folks name it 'Gwenc'hlan's Prediction'. It displays "all characteristic features of the Welsh Bardic poetry of the 5th and 6th centuries... which is combined with more heathenism and outspoken hatred of the Church of Christ as a whole." - La Villemarqu�'s son, Pierre, published in 1908 a letter received from his cousin Camilla, stating that Marie-Jeanne Penquerc'h n�e Droal from Penanros near Nizon (1806 - 1892), who is included on the lists of singers set up by the Bard's mother (who ascribes this song to Anna�k Huon, wife of Breton, from Kerazul near Nizon), remembered very well some old, rare songs, among them "Gwenc'hlan's prophecy" (for which La Villemarqu� states in the song's "argument": "collected at Melgven, sung by Guillou Ar Gall").

This coincids with the Reverend Gregory's statement in the introduction to his Dictionary (List of authors used to compose this dictionary):

"Guinclan...still very famous among today's Bretons [1732].

They usually refer to him as 'the Prophet Guinclan'" - Besides, no major changes in the text (except the word "kurun" =thunder changed for "taran"="thundering") appear when comparing the 1839 edition, when the young author could only rely upon his own linguistic resources, with the next one, released in 1845, when help of a new collaborator, the native Breton speaker Abb� Henry was available.

Therefore we must not needs consider this song as a spurious fiction, even if the genuine original was thoroughly "trimmed" as was apparently the collector's wont. - Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville, though very sceptical as to the origin of the "historical" songs in the Barzhaz, investigates the poem at hand in his "Study on the first and sixth edition of the Breton Folk Songs" published in 1867 in the bulletin "Biblioth�que de l'Ecole des Chartes", book 28, p. 272, in terms clearly showing that he considers it genuine folk poetry. Concerning some minor changes made by the author between both editons, he approves the replacement of "vorc'higo" (piglets, stanza 12) and "kerno" (horns, stanza 14) with, respectively "voc'higo�" and "kernio�", but questions, at stanza 24 the change of "ezned" (birds) for the modern "evned" and, at stanza 8, that of "Deuz forz petra a c'hoarvezo" (inevitably comes what shall happen), for "Na vern petra a c'hoarvezo", a change made to justify the originally faulty translation: "I don't care what will happen".

He is no more lenient for petty changes intended to conform the text with Le Gonidec's grammar rules: he removed the double archaism "and erc'h gann" (the white snow, a feminine word, stanza 14), replaced by "an erc'h kann" (the modern masculine noun preceded by the usual article; the imperfect "me a gane" (I sang) instead of the old conditionnal "me ganefe" (I would sing), with an inset "e". Another reason is the wish to create additional alliterations: "Pa" (when), repeated four times in stanzas 1 and 2, instead of "Ma" (if). The same wish for alliterations prompted La Villemarqu� to rewrite stanza 15:

An dour dindan hen o firvi

Gant an tan gurun euz he fri.

becomes:

An dour dindana� o virvi�

Gant an tan daran eus e fri.

Similarly stanza 14:

En ken gwenn ewid an erc'h gann.

becomes:

E� ken gwenn evel an erc'h kann,

whereas, if he had only respected the rules set forth by Le Gonidec, he would have written:

E� ker gwenn evit an erc'h kann,

in which no alliteration is left.

Jubainville would cetainly not have dedicated over half of his study(almost 8 pages) to a text he had considered a mere fake that could be tampered with without inconvenient. Therefore we must not needs consider this song as a spurious fiction, even if the genuine original was thoroughly "trimmed" as was apparently the collector's wont.

The romantic authors and Gwenc'hlan - The "Notes and Comments" in the 1839 edition of the Barzhaz mention that the ascription (in the "Argument") to Gwenc'hlan of this piece where his name appears nowhere is justified by stanza 23, since the prophet "so says the Reverend Gregory of Rostrenen, declares at the beginning of his 'Predictions' "that he [wrote in the year of grace two hundred fifty, when he] was dwelling between Roc'h-Hellas and Porz-Gwenn in the bishopric Tr�guier, between Morlaix and Tr�guier town" [Introduction: List of authors used by the Reverend Gregory to prepare his dictionary].

In 1852 Abb� Daniel assigned Guinclan his stand on the rock "where Bard Gwenc'hlan so oft called a curse on the Christian faith that was spreading over our country...A cross was recently erected on Roc'h-Allaz point: another refutation of Gwenc'hlan's soothsaying" ("Biblioth�que bretonne", Saint-Brieuc II, p.761). The same views are expressed by Anatole de Barth�l�my in his "Miscellanies on Breton History", I, 1853, p.58 and Benjamin Jollivet in his "Geographic description of the D�partement C�tes-du-Nord", IV, 1859, p.123. - This "tradition" was in contradiction with another, as stated by R. Largilli�re in "Annals od Brittany", book 37, N�3-4, p.300, which located in B�gard the dwelling place of the prophet whose grave was believed to be hidden in the abbey church of that parish, 6 km north-east of M�nez-Br� Mound. In fact this fiction was created by an obscure writer, Poignand, in a book titled "Antiquit�s historiques et monumentales de Montfort � Corseul" published in Rennes in 1820, for he considered that B�gard and Guinclan were two words meaning "excellent mouth"! These wild imaginings are of importance, inasmuch as they were widely spread: they were taken up by another also rather obscure author, Marchandy, in 1825, in his "Tristan the Traveller".

- As for Kerdanet's views that the M�nez-Br� harboured the hiding place then the grave of Guinclan, they are shared by a great many authors: Le Maout ("Annales Armoricaines", Saint-Brieuc, 1846, p.38), the continuators of the geographer Og�e, (in 1853, under item "P�dernec"), Pol de Courcy ("Itin�raire de Rennes � Saint-Malo", 1864, p.194), S. Ropartz ("Histoire de Guingamp",2nd edition, I, p.15, in 1859), Geslin de Bourgogne and A. de Barth�l�my ("The Former bishoprics of Brittany", III, I, p. ix, in 1864)...

Two "barbarous" sayings

As stated in connection with the "Welsh Gwenc'hlan", La Villemarqu� followed this example and quoted "Gwenc'hlan revisited by Kerdanet" as from the first 1839 edition of the Barzhaz (pp. xi, xii et 11):

"Future shall hear of Gwenc'hlan..." and "Some day the Christian priests shall be hunted down like wild beasts". - In addition to this litterary references La Villemarqu� mentions two barbarous sayings" in the 1845 edition which may also have inspired his poem:

"Tud Jezus-Krist a wallgasor / Evel gouezed o argador" (A day will come when the priests of Christ will be hunted down and harried like wild beasts).

In the 1839 edition, the readers of Kerdanet's "History of the language of the Gauls" were reminded of a passage with the same meaning quoted by this author, but this precision is missing in the later editions

and - "Rod ar vilin a valo flour / Gand goad ar venec�h eleac�h dour." (The wheels of the mills shall grind fine with blood of monks instead of water).�

A similar sentence (in French) could be found in Dufilhol's "Guyonvarc'h" (Paris, 1835, pp.26, 109 and 163): "Soak, soak your mill. It wants to spin in blood". R. Largilli�re in "Annales de Bretagne", book 37, N�3-4, p.300, in 1925, considered it a bit of Lower-Tr�gor folk doggerel.

The genuineness of this phrase is apparently guaranteed by the grammarian Fran�ois Vall�e who read a paper at the 1912 meeting of the "Association Bretonne", in Moncontour, to the effect that he had collected, as he said, "rhymed prophecy" about Guinklan's coming back to life, the terrible combat that will take place and "the mills on Green Island that shall be driven by streams of blood". This statement is met with extreme scepticism by the author, in 1960 of the afore-mentioned "La Villemarqu� and the Barzaz-Breiz", Francis Gourvil.

The Gwynglaff in the "Dialogue with King Arthur"

In 1924, the linguist and writer, Francis Gourvil (1889 - 1984) discovered in the attic of a manor at Locqu�nol�, near Morlaix, following the sale by auction of a book collection, a handwritten poem consisting of 247 lines in Dom Le Pelletier's handwriting, composing the famous prophecy and titled "An dialog etre Arzhur, Roue d'an Bretounet ha Guynglaff" ( A Dialogue between Arthur King of the Bretons and Guinclan), followed by the words "In the year of grace A thousand four hundred and fifty".

The original copyist was ill-advised enough to cross out the words "a thousand" (which accounts for the Reverend Gregory's mistake) but, to blame this erasure Dom Pelletier hinted at the many French words in the text, for instance the word "canol" (cannon).

This "Dialogue" where Guinclan is not mentioned as the author but as a protagonist is made up as follows according to the description made by R. Largilli�re in the "Annals of Brittany" (Book 38, 1929):

1� Life of Gwynglaff, a half-wild being who has no other dwelling than the trees in the forests where he roams clad in a reddish cloak. He can foretell the future. Consequently he is a figure similar to the "wylde man" depicted in the song Merlin the Bard.

2� One Sunday, King Arthur [an ancient reference contributing to explain Gregory of Rostrenen's error] captured him and ordered him under threat to unveil what misfortunes were to befall Brittany until Doomsday.

3� Answer: "You shall know all except the date of your death and mine" followed by statements impossible to elucidate: summer and winter merging together; hoary youngsters; worst soil yielding the best wheat [confirming La Villemarqu�'s assertion]; heretics challenging the law of God, etc.

4� Predictions for the years 1570 to 1575 and 1587- 1588.

5� A lengthy answer to the king's question: wars and destructions for which the sole English are blamed. Threatened to be beheaded, weaponless and armed Bretons alike will have to combat enemies. They will die, lots of them, on the M�nez Br�, whole legions; they will have to besiege Guingamp, pull down its walls and plunder its goods, rape the girls and slaughter men and women. As a punishment inflicted by God the Saxons shall take possession of Brittany.

The phrases in bold characters were quoted by several authors even before the MS was rediscovered. Others are included in the two dictionaries drawing on them, but were not found on the MS: the word "orzail" (Le Pelletier) and the sentence to the effect that Guinclan "dwelt between Roc'h-Hellas and Porz-Gwenn" (Gregory). On the manuscript, Dom Le Pelletier mentions 2 versions of the Prophecies. Maybe these words were included on the missing version which he had shown the Rev. Gregory.

As stated by J. Tourneur-Aumont in the same "Annals", this poem is a "Chant royal" composed in accordance with standards set in the 15th century to serve the interests of the king of France, Charles VII. This text may be of philological but , by no means of historical value. F. Gourvil notes that there is no indication that it was Land�vennec Abbey's property or that it was destroyed by the Revolution.

In an epitome on "Breton Language and Literature" published in 1952, in the "Que sais-je? collection, F. Gourvil insidiously remarks that his discovery " made futile any new attempt by diverse authors who believed that this text was lost for ever, to ascribe to the old bard their own writings." It is evident that, in saying so, he hints at La Villemarqu�.

It is nonetheless evident that the latter never pretended he was reconstructing any of the lost "prophecies", only contributing a piece of oral lore.

Far from invalidating the young Bard's statements, this piece corroborates them: - It contains two aphorisms quoted by him: "the worst soils...", "they'll die on the M�nez-Br�..." ; (This second quote can be found on page 65 of La Villemarqu�'s Third record book, published in November 2018, followed by the sentence 'Savan ma mouez war ar Menez-Bre "=" I raise my voice on the M�nez-Br�"). This passage concludes a description of this hill, of the chapel which surmounts it, of a menhir cut to give it the form of a cross, of the fair which is held there on June 17, feast of Saint Herv�. It is decorated with drawings of the cross-menhir, a door and a coat of arms bearing ermines, bells and rings.

Saint-Herv� Chapel nowadays (Photos J. Philippe-Quentin) - It makes of Gwynlaff a contemporary of King Arthur's, another legendary figure who, so writes Nennius in his "Historia Brittonum" (ca. 960), fought against the Saxons in particular at the Battle of Mount-Badon which another document, the "Annales Cambriae (also ca 960) dates to 516. If Gwenchlan did live , he lived in the 6th century.

Anatole Le Braz' Gwenc'hlan

As we saw on the Series page Anatole Le Braz was a severe critic of La Villemarqu�'s collection. Yet, in his "Tales of Sun and Mist" (1905) he wrote a very inspiring description of the M�nez-Br�, a 300 meter "mount" west of Guingamp which he assures:

"Was the place where the 6th century Bretons deliberately located the sepulchre of their famous Gwenc'hlan whose memory and songs had accompany them on their exodus. A Bard and a prophet like Merlin, Gwenc'hlan, whose name means "Holy race", was considered one of his most brilliant disciples."

Le Braz does not jib at quoting the first three stanzas of the Barzhaz Breizh poem when he evokes "the bitter moan placed into his mouth, in his collection, by Viscount de La Villemarqu�". He adds:

"Throughout old "Domnonea" [the area along the North coast of Brittany], his predictions were well-known. They even were committed to writing and some of them were allegedly kept, two hundred years ago by the monks of Land�vennec. Today it is only in the folk's memory that you may look for an albeit fading echo of the sibylline words of his 'diou-gano�'".

The source of the oral tradition about this prophet is none other than Marguerite Philippe alias Marc'harid Fulup (1837 -1909). Also known as 'Godik ar Vognez' (One-armed Maggie), she was Luzel's main informer at Plouaret and he learned of her singing over 259 songs. In the present case she conveyed tales about the mysterious character. - He dwelled in Manor Run-ar-Gov west of the mount

and, like an owl, he could turn his head all the way round. - He was aware of things to come, but he spoke little except with crows and migrating birds that would inform him of events afar.

- Once, he fought an invisible foe, wielding his sword from dawn to sunset, atop the M�nez-Br�. He had slain a horde of invaders of the future and the clouds in the sky hung red with their blood.

- With the feather quill of a sea eagle he wrote his last will and testament. His riches were immense and he would keep them, along with his books and his secrets, in his grave that would be held of all unknown. The Bretons should go on living in poverty from which their keenest joy arises. Twelve wagons, heavily loaded with gold and driven by blindfold men, were led around the M�nez-Br� several times, until their load was engulfed by a bottomless pit. Then a profound sigh was heard. That's all what's known about Gwenc'hlan's death.

- "Every hundred years, so they say, in the first new moon night, the M�nez-Br� cracks open...If you were bold enough to slip in, a magic radiance would lights up the place and you would be guided down to Gwenc'hlan ... [whose] ghost haunts the depths of the mount, as does Saint Herv�'s spirit the top of it." (The M�nez-Br� is topped by a chapel dedicated to this holy man: one miracle-worker is replaced by another).

Similar fictional stuff is reported by M. Le Teurs in the "Journal of the Finist�re Archaeological Society" (1875-1876, p.179). It is about the parish Saint-Urbain in Finist�re where a mound, named "Torgen ar Sal" is considered to be "Gouincl�'s grave" where he rests with his treasures.

The customary interpret of Marguerite Philippe, Fran�ois-Marie Luzel, never heard of Gwenc'hlan. At the very most he could report:

"At Louargat, at the foot of the M�nez-Br�, an old woman whom I asked told me once that there was in former times on top of the mount, ur warc'hlan. Was it an alteration of Gwinglaff? Besides, she could not say if it was a man or an animal."

The conclusion drawn by R. Largilli�re from these elements in his study on Gwenc'hlan, is that

"

the literary fictions created by 19th century authors have pervaded the imagination of the country folks"

and that, far from truly reporting, as he asserts he does, Marguerite Philippe's narrative, Anatole Le Braz embellished it a great deal. This is all the more probable, in his opinion, since in an article published in "La Plume" on 1st March 1894, he wrote:

"Who had not loved to depict as part of genuine lore this great bardic spectre ... atop the lonely M�nez-Br�? [as did La Villemarqu�] ...But a serious critic must kiss it goodbye. I don't resign myself to it without regret".

Did Le Braz, eleven years later, really succumb to the mirage and inflict on the popular muse the dishonesty for which he used to reproach La Villemarqu� ? One may doubt it.

Is the Barzhaz Breizh: A "bad book"?

In 1960 F. Gourvil becomes more peremptory and at Rennes University he submits an essay published later on under the revealing title: "The authenticity of the Barzaz Breiz :How its defenders try to rescue a bad book". Then, in 1966, he criticizes, maybe with some reasons, "The language of the Barzaz Breiz and its irregularities".