Emergent Management of Atrial Flutter: Overview, Emergency Department Care, Cardioversion for Unstable Patients (original) (raw)

Overview

Overview

Atrial flutter is the second most common tachyarrhythmia, after atrial fibrillation. This condition has traditionally been characterized as a macroreentrant dysrhythmia with the re-entrant loop just above the atrioventricular (AV) node in the right atrium. Atrial rates are generally between 240 and 360 beats per minute (bpm) without medications.

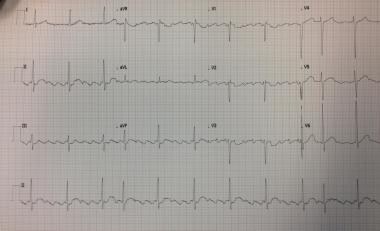

The electrocardiogram (ECG) usually demonstrates a regular rhythm, with P waves that can appear sawtoothed (see the image below), also called flutter waves, usually best visible in lead II. The QRS complex is narrow if there is no aberrancy. Because the AV node cannot conduct at the same rate as the atrial activity, some form of conduction block is often seen, typically 2:1 (most common), 3:1, or 4:1. This block may also be variable and cause atrial flutter to appear as an irregular rhythm.

Twelve-lead ECG showing atrial flutter with variable block.

Atrial flutter can arise from conditions that lead to atrial dilatation. These include chronic left-sided congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolus, valvular heart disease (especially mitral and tricuspid diseases), and septal defects. Metabolic conditions such as hyperthyroidism and alcoholism can also cause atrial flutter. Rarely, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter may be due to pericardial disease or effusion or caused by carbon monoxide intoxication.

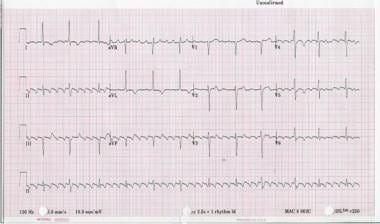

Twelve-lead ECG of type I atrial flutter. Note negative sawtooth pattern of flutter waves in leads II, III, and aVF.

See Atrial Flutter and Pediatric Atrial Flutter for complete information on these topics.

Prehospital care

Prehospital treatment is usually only indicated in hemodynamically unstable patients. Refer to local protocols for emergency medical services (EMS) management.

Atrial flutter in an unstable patient should be treated immediately with synchronized cardioversion. Unstable patients are those with ongoing chest pain, severe shortness of breath, altered level of consciousness, or hypotension. The patient should be treated with an intravenous (IV) sedative prior to cardioversion if their condition permits.

In general, avoiding class I and III agents (eg, procainamide) in the prehospital setting is safest because of possible induction of a 1:1 conduction. Frequently, the rate can be slowed safely with administration of calcium channel blockers (class IV) or beta-adrenergic blockers (class II). Avoid giving procainamide or similar-acting medications prior to slowing the AV node conduction (eg, diltiazem), as slowing the atrial rate prior to the AV conduction rate can dangerously increase the ventricular rate by the induction of a lower conduction ratio (eg, inducing a 1:1 conduction as the atrial rate slows to 220 bpm in a patient who was initially exhibiting a 2:1 conduction at a rate of 300 A/150 V. As the atrial rate slows to 220 bpm, the ventricular rate increases to 220 bpm and the patient becomes less stable.).

For patient education information, see the Heart Health Center, as well as Atrial Flutter, Arrhythmias (Heart Rhythm Disorders), Stroke, Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT, PSVT), and Palpitations.

Emergency Department Care

At the time of this update, there is no consensus on the optimal management of atrial flutter in the emergency department, due to a lack of robust evidence, as well as a wide variation in typical management. Hemodynamic concerns should always dictate initial treatment: This begins with an adequate and immediate assessment of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation ("ABCs").

Treatment goals include the following:

- Conversion to normal sinus rhythm

- Keeping the patient in normal sinus rhythm

- Control of the ventricular rate

- Preventing thromboembolic disease

Treatment options for atrial flutter include the following [1] :

- Direct-current (DC) cardioversion

- Antiarrhythmic drugs/nodal rate control agents

- Rapid atrial pacing to terminate atrial flutter

Blood pressure can be supported and rate controlled with medication.

Look for underlying causes for atrial flutter. At times, treatment of the underlying disorder (eg, thyroid disease, valvular heart disease) is necessary to effect conversion to sinus rhythm.

Cardioversion for Unstable Patients

If the patient is unstable (eg, hypotension, poor perfusion), synchronized direct-current (DC) cardioversion is the initial treatment of choice.

Cardioversion may be successful with energies as low as 25 joules, but 100 joules is usually successful and is therefore a reasonable initial shock strength. Higher energy levels are occasionally required.

If the electrical shock results in atrial fibrillation, a second shock at a higher energy level is used to restore normal sinus rhythm.

Rate Control With Nodal Agents

To slow the ventricular response, administration of calcium channel blockers (CCBs) such as diltiazem, or beta blockers such as esmolol, are commonly used as initial treatment. Beta-adrenergic blockers are especially effective in the presence of thyrotoxicosis and increased sympathetic tone.

Calcium channel blockers

CCBs reduce the rate of atrioventricular (AV) nodal conduction and control the ventricular response.

Beta blockers

Beta blockers slow the sinus rate and decrease AV nodal conduction. Carefully monitor the patient's blood pressure.

Cardiac glycosides

Cardiac glycosides decrease AV nodal conduction primarily by increasing vagal tone. These agents are used mainly in the context of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter with congestive heart failure. Digoxin can be administered alone or with either a calcium antagonist or a beta blocker.

Digoxin toxicity is very rarely a cause of atrial flutter; however, ascertaining that atrial flutter is not caused by digoxin toxicity is important.

Adenosine

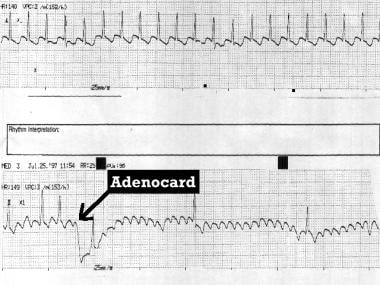

Adenosine produces transient AV block and can be used to reveal flutter waves (as demonstrated in the image below).

Type I atrial flutter unmasked by adenosine (Adenocard).

Rhythm Control in Stable Patients

Other antiarrhythmic drugs that can terminate atrial flutter/fibrillation include amiodarone and procainamide, as well as disopyramide, propafenone, sotalol, flecainide, and ibutilide.

Class I antiarrhythmics

Class I antiarrhythmic agents are used for chemical conversion into sinus rhythm. They alter the electrophysiologic mechanisms responsible for arrhythmias. As discussed earlier, it is dangerous to administer procainamide prior to slowing the AV node conduction (eg, with diltiazem), as slowing the atrial rate prior to the AV conduction rate can actually increase the ventricular rate by the induction of a lower conduction ratio (eg, inducing a 1:1 conduction at a rate of 200 bpm from a 2:1 conduction at a rate of 300 A/150 V)!

Class III antiarrhythmics

Class III antiarrhythmic agents establish a chemical conversion to sinus rhythm.

Intravenous amiodarone has been shown to slow the ventricular rate and is considered as effective as digoxin. Amiodarone has less negative inotropy than calcium channel blockers or beta blockers and can be used in patients with hemodynamic compromise. However, this drug can convert an atrial flutter to normal sinus rhythm—and this may have thromboembolic risk.

Antithrombotic Therapy

The 2014 American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society (AHA/ACC/HRS) guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) includes recommendations regarding antithrombotic treatment for patients with atrial flutter. [2] The recommendations are summarized below.

For patients with atrial flutter, the recommendations for antithrombotic therapy are according to the same risk profile used for those with AF. [2] Selection of antithrombotic therapy should be made on the basis of the risk of thromboembolism, irrespective of whether the dysrhythmia pattern is paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent.

For patients with AF with mechanical heart valves, warfarin is recommended. [2]

For patients with nonvalvular AF and history of a previous stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), oral anticoagulants (eg, warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) are recommended. [2]

In all other patients with nonvalvular AF, the CHA2DS2-VASc score is recommended to assess stroke risk. [2] CHA2DS2-VASc = congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (doubled), diabetes, stroke/TIA/thromboembolism (doubled), vascular disease (prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque), age 65-75 years, sex category (female).

For patients with nonvalvular AF and the following CHA2DS2-VASc scores [2] :

- 2 or greater: Oral anticoagulants are recommended. For those with severe or end-stage chronic renal disease, warfarin remains the anticoagulant of choice. (Class IIa recommendation)

- 0: It is reasonable to omit antithrombotic therapy. (Class IIa recommendation)

- 1: No antithrombotic therapy, aspirin only, or oral anticoagulant therapy may all be considered. (Class IIb recommendation)

Treatment Concerns

Closely monitor patients for the development of severe bradycardia during treatment. Severe hypotension and death may ensue if the cardiac rhythm is not carefully tracked.

Some patients with atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation and a preexcitation syndrome (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome) are at risk for 1:1 conduction via their accessory pathway when nodal agents preferentially block the atrioventricular (AV) node. This can cause ventricular fibrillation.

A cardiologist may become involved primarily if the patient presents with complicating factors or an obvious ongoing cardiac ischemia (or infarction) that is not treatable with rate reduction measures and standard chest pain protocols.

Inpatient Care

Catheter ablation treatment

Antiarrhythmic drugs alone control atrial flutter in only 50-60% of patients. Since the early 1990s, radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFA) has been used to interrupt the reentrant circuit in the right atrium and prevent recurrences of atrial flutter. The cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI) is the part of the circuit in the right atrium that is targeted by ablation. Radiofrequency ablation is immediately successful in more than 90% of cases and avoids the long-term toxicity observed with antiarrhythmic drugs. It is the long-term treatment of choice in patients with symptomatic atrial flutter.

A study by Saygi et al that involved 153 randomized patients indicated that in cases of CTI-dependent atrial flutter, RFA and cryoablation each cause a similar degree of procedural myocardial injury, as measured by increased troponin I levels after the procedure. [3] The same investigators found similar procedural success rates between RFA and cryoablation for CTI-dependent atrial flutter, regardless of the CTI morphology (straight, concave, and pouchlike). [4] However, patients with a longer CTI experienced a lower procedure success rate whether the energy source was RFA or cryoablation. [4]

In patients who have failed antiarrhythmic therapy or who have failed radiofrequency ablation and who are symptomatic, palliative therapy with AV-His Bundle ablation can eliminate rapid ventricular rates, but it does require a permanent pacemaker to be placed, as this procedure creates third-degree heart block.

Transfer

Transfer to a referral center may be indicated for patients who present to the emergency department with complications of atrial flutter, including the following:

- Bradycardia (eg, from sick sinus syndrome) requiring pacemaker therapy

- Unresponsive rate despite adequate medical therapy; after electrical cardioversion, referral for electrophysiologic ablation may be appropriate (These patients are generally transferred from one inpatient facility to another.)

- Embolic complications requiring surgical therapy (ie, arterial embolization), cerebrovascular accident, atrial fibrillation, or atrial flutter requiring neurointensive care

Guidelines Summary

In 2015, the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society (ACC/AHA/HRS) released joint guidelines for the management of supraventricular tachycardia which include an algorithm for acute treatment of atrial flutter. [5] These are summarized below.

Acute treatment

Hemodynamically unstable patients [5]

For rhythm control, synchronized cardioversion is recommended. (Class I recommendation)

For rate control, intravenous (IV) amiodarone is recommended. (Class IIa recommendation)

Hemodynamically stable patients [5]

For rhythm control, the following are recommended (all class I recommendations):

- Synchronized cardioversion, oral dofetilide, IV ibutilide, and/or rapid atrial pacing

- Rapid atrial pacing in patients who have pacing wires in place as part of a permanent pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or for temporary atrial pacing after cardiac surgery

- Elective synchronized cardioversion

Note that synchronized cardioversion or rapid atrial pacing is not appropriate for rhythms that break or spontaneously recur.

For rate control, beta blockers, diltiazem, or verapamil is recommended. (Class I recommendation) [5] IV amiodarone is recommended when beta blockers are contraindicated. (Class IIa recommendation)

Additional Studies

In a study by Stiell et al, the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol, which includes chemical cardioversion; electrical cardioversion, if needed; and discharge home from the emergency department (ED), was found to possibly be safe, rapid, and effective, and to be potentially capable of reducing hospital admission. [6] Further study of this protocol is needed.

A Canadian study suggested that patients treated in the ED for uncomplicated atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter who are at particular risk for associated stroke may not, in many cases, receive anticoagulant therapy. [7] The investigators found that of the 732 patients in the study who were discharged from the ED without cardiologic consultation (including 75 with atrial flutter), a significant number did not receive appropriate anticoagulation.

Similarly, a 2017 multicenter report by Stiell et al that prospectively evaluated management and 30-day outcomes in 1091 ED patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation (84.7%) or atrial flutter (15.3%) found that oral anticoagulants were underprescribed and that patients discharged from the ED in sinus rhythm had a smaller likelihood of experiencing an adverse event. [8] More than 10% of all patients had adverse events within 30 days, including 1 case of stroke, but no deaths were reported. Potential risk factors for adverse events included longer duration from arrhythmia onset, radiographic evidence of pulmonary congestion, previous history of stroke/transient ischemic attack, and ED discharge without being in sinus rhythm. [8]

Questions & Answers

- Hamilton A, Clark D, Gray A, Cragg A, Grubb N, for the Emergency Medicine Research Group Edinburgh (EMERGE). The epidemiology and management of recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter presenting to the Emergency Department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2015 Jun. 22(3):155-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al, for the ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014 Dec 2. 130(23):2071-104. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Saygi S, Drca N, Insulander P, Schwieler J, Jensen-Urstad M, Bastani H. Myocardial injury during radiofrequency and cryoablation of typical atrial flutter. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2016 Aug. 46(2):177-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Saygi S, Bastani H, Drca N, et al. Impact of cavotricuspid isthmus morphology in CRYO versus radiofrequency ablation of typical atrial flutter. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2017 Apr. 51(2):69-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, et al, for the Evidence Review Committee Chair‡. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tyachycardia: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2016 Apr 5. 133(14):e471-505. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Stiell IG, Clement CM, Perry JJ, et al. Association of the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol with rapid discharge of emergency department patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation or flutter. CJEM. 2010 May. 12(3):181-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Scheuermeyer FX, Innes G, Pourvali R, et al. Missed opportunities for appropriate anticoagulation among emergency department patients with uncomplicated atrial fibrillation or flutter. Ann Emerg Med. 2013 Dec. 62(6):557-65.e2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, et al. Outcomes for emergency department patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter treated in Canadian hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 2017 May. 69(5):562-571.e2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sassone B, Leone O, Martinelli GN, Di Pasquale G. Acute myocardial infarction after radiofrequency catheter ablation of typical atrial flutter: histopathological findings and etiopathogenetic hypothesis. Ital Heart J. 2004 May. 5(5):403-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lin JH, Kean AC, Cordes TM. The risk of thromboembolic complications in Fontan patients with atrial flutter/fibrillation treated with electrical cardioversion. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016 Oct. 37(7):1351-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gould PA, Booth C, Dauber K, Ng K, Claughton A, Kaye GC. Characteristics of cavotricuspid isthmus ablation for atrial flutter guided by novel parameters using a contact force catheter. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016 Dec. 27(12):1429-36. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rodriguez Y, Althouse AD, Adelstein EC, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of concurrently diagnosed new rapid atrial fibrillation or flutter and new reduced ejection fraction. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2016 Dec. 39(12):1394-403. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Borlich M, Weinert R, Becker B, Kuhnhardt K, Richardt G, Iden L. Radiofrequency ablation of typical atrial flutter with access through the azygos vein in a patient with heterotopia utilizing high-density electroanatomic mapping. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2018 Oct. 4(10):466-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Vinson DR, Lugovskaya N, Warton EM, et al, for the Pharm CAFE Investigators of the CREST Network. Ibutilide effectiveness and safety in the cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and flutter in the community emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Jan. 71(1):96-108.e2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Twelve-lead ECG of type I atrial flutter. Note negative sawtooth pattern of flutter waves in leads II, III, and aVF.

- Type I atrial flutter unmasked by adenosine (Adenocard).

- Twelve-lead ECG showing atrial flutter with variable block.

Author

Jesse Borke, MD, FACEP, FAAEM Associate Medical Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Alamitos Medical Center

Jesse Borke, MD, FACEP, FAAEM is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American Association for Physician Leadership, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Chief Editor

Barry E Brenner, MD, PhD, FACEP Program Director, Emergency Medicine, Einstein Medical Center Montgomery

Barry E Brenner, MD, PhD, FACEP is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Physicians, American Heart Association, American Thoracic Society, New York Academy of Medicine, New York Academy of Sciences, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Edward Bessman, MD, MBA Chairman and Clinical Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, John Hopkins Bayview Medical Center; Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Edward Bessman, MD, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Pierre Borczuk, MD Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Associate in Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital

Pierre Borczuk, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors and editors of Medscape Reference gratefully acknowledge the contributions of previous authors Alan D Clark, MD†, Jeffrey Lazar, MD, and Vivek Parwani, MD,to the development and writing of the source article.

- Sections Emergent Management of Atrial Flutter

- Overview

- Emergency Department Care

- Cardioversion for Unstable Patients

- Rate Control With Nodal Agents

- Rhythm Control in Stable Patients

- Antithrombotic Therapy

- Treatment Concerns

- Inpatient Care

- Transfer

- Guidelines Summary

- Additional Studies

- Questions & Answers

- Show All

- Media Gallery

- References