Pediatric Adrenal Insufficiency (Addison Disease): Practice Essentials, Anatomy, Etiology (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

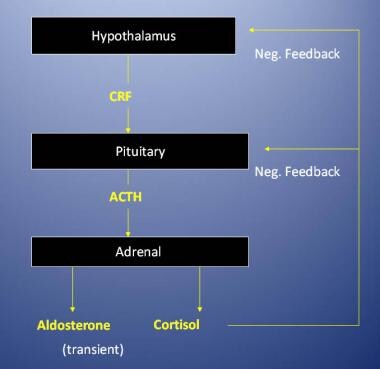

Adrenal insufficiency can be classified as primary (Addison disease), which occurs when the adrenal gland itself is dysfunctional, or secondary, also called central adrenal insufficiency, which occurs when a lack of secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus or of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary leads to hypofunction of the adrenal cortex. [1, 2] See the image below.

Regulation of the adrenal cortex. ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; CRF = corticotropin-releasing factor; neg. = negative.

Adrenal insufficiency can further be classified as congenital or acquired (see Etiology).

Signs and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency

Patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency usually have the following:

- Chronic fatigue

- Anorexia

- Asthenia

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Recurring abdominal pain

- Weakness and a lack of energy

Increased skin pigmentation and salt craving are common among individuals with chronic primary adrenal insufficiency.

Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency

Clinical suspicion is important because the presentation of patients with adrenal insufficiency may be insidious and subtle.

A diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is confirmed if the serum cortisol level is less than 18 mcg/dL in the presence of a markedly elevated serum adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) concentration and plasma renin activity. Based on normative data of children of various ages, adrenal insufficiency is likely if the serum cortisol concentration is less than 18 mcg/dL 30-60 minutes after intravenous (IV) administration of 250 mcg of cosyntropin (synthetic ACTH 1-24) in children over age 2 years. The cosyntropin test dose may be decreased to 15 mcg/kg for infants and 125 mcg for children under age 2 years. [3, 4, 5] These criteria may not apply to premature or low-birth-weight infants, who have low cortisol secretion and, most likely, decreased cortisol binding to carrier proteins. [6] Therefore, the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency in premature infants remains problematic.

When a patient's serum cortisol response to cosyntropin is subnormal but his or her serum ACTH level is not elevated, the possibility of central adrenal insufficiency should be considered.

Because the adrenal glands may not have had sufficient time to atrophy in the absence of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation, the relatively cumbersome and risky insulin-tolerance test or metyrapone stimulation test may be preferable to a cosyntropin challenge if the patient has recent-onset (ie, < 10 d) central adrenal insufficiency (eg, a patient who recently underwent surgery of the hypothalamus or pituitary regions). The insulin-tolerance test is still considered the criterion standard.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the imaging study of choice in the evaluation of adrenal insufficiency and helps to identify adrenal hemorrhage, calcifications, and infiltrative disease.

Histologic findings in adrenal insufficiency depend on the underlying cause. CT scan–guided fine-needle aspiration sometimes helps in diagnosing the etiology of infiltrative adrenal disease.

Management of adrenal insufficiency

Patients with adrenal insufficiency are generally hypovolemic and may be hypoglycemic, hyponatremic, or hyperkalemic. Initial therapy consists of intravenously administered saline and dextrose. Potassium is generally not needed in acute situations, especially in patients with primary adrenal insufficiency, who are often hyperkalemic.

Glucocorticoid replacement is required in all forms of adrenal insufficiency. Mineralocorticoid replacement is required only in primary adrenal insufficiency, because aldosterone secretion is reduced in primary adrenal insufficiency but not in central adrenal insufficiency.

No surgical management is needed in most cases of adrenal insufficiency.

See also Addison Disease.

Anatomy

The adrenal cortex is divided into 3 major anatomic zones. The zona glomerulosa produces aldosterone, and the zonae fasciculata and reticularis together produce cortisol and adrenal androgens. A fetal zone, unique to primates, produces dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), a precursor of both androgens and estrogens. This zone involutes within the first few months of postnatal life.

Aldosterone secretion is primarily regulated by the renin-angiotensin system. Increased serum potassium concentrations can also stimulate aldosterone secretion. Cortisol secretion is regulated by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which, in turn, is regulated by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus. Serum cortisol inhibits the secretion of both CRH and ACTH to prevent excessive secretion of cortisol from the adrenal glands.

ACTH partially regulates adrenal androgen secretion; other unknown factors contribute to this regulation as well. ACTH not only stimulates cortisol secretion but also promotes growth of the adrenal cortex in conjunction with growth factors such as insulinlike growth factor (IGF)-1 and IGF-2. [7]

Etiology

Iatrogenic central adrenal insufficiency as well as acquired and congenital primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease) are briefly discussed in this section.

Iatrogenic central adrenal insufficiency

Most cases of adrenal insufficiency are iatrogenic, caused by long-term administration of glucocorticoids. A mere 2 weeks' exposure to pharmacologic doses of glucocorticoids can suppress the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)–adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)–adrenal axis. The suppression can be so great that acute withdrawal or stress may prevent the axis from responding with sufficient cortisol production to prevent an acute adrenal crisis. Similar suppression can be seen in individuals on chronic high doses of inhalable glucocorticoids. [8]

Treatment with megestrol acetate, an orexigenic agent, has also resulted in iatrogenic adrenal suppression. The mechanism is presumably related to the glucocorticoid properties of megestrol acetate. [9]

A study by Gibb et al found that in four out of 48 patients on long-term opioid analgesia for chronic pain (8.3%), the basal morning plasma cortisol concentration was below 100 nmol/L (3.6 ng/dL), indicating that such treatment can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in a clinically significant proportion of patients. [10]

Other causes of central adrenal insufficiency include congenital or acquired hypopituitarism and ACTH unresponsiveness.

A retrospective cohort study by Josephsen et al indicated that in extremely premature infants, combining budesonide with dexamethasone significantly increases the risk of presumed adrenal insufficiency. In infants with less than 28 weeks’ gestation, the incidence of presumed adrenal insufficiency was 20.8% in those who had received dexamethasone for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, compared with 2.9% in those who did not. However, as used in intubated neonates who received a surfactant, an independent association with presumed adrenal insufficiency did not exist for dexamethasone after adjustment was made for gestational age, birthweight, and race. Nonetheless, in infants who had previously received budesonide/surfactant therapy, dexamethasone was independently associated with such insufficiency, the adjusted odds ratio being 5.38. [11]

Hypopituitarism with adrenal insufficiency can be a secondary manifestation of a sellar or suprasellar mass, an inflammatory or infiltrative process, surgery, or cranial irradiation. Congenital unresponsiveness to ACTH that can occur if the ACTH receptor is absent or altered can clinically mimic this condition. However serum ACTH concentrations can help to distinguish between the two. [12, 13] ACTH unresponsiveness may be isolated (as in Familial Glucocorticoid Deficiency) (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database [OMIM] 202200), [12, 14] or it may be associated with achalasia and alacrima (as in achalasia-addisonism-alacrima syndrome, or triple A syndrome [AAAS]) (OMIM 231550). [15, 16] .

Acquired primary adrenal insufficiency

In developed countries, the most common cause of adrenal insufficiency is autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex. [17] This disorder may occur in isolation or may be part of a polyglandular autoimmune disorder (PGAD).

Patients with type 1 PGAD (OMIM 240300) usually present in the first decade of life with mucocutaneous candidiasis or hypoparathyroidism. This is an autosomal recessive disorder that involves the AIRE gene on chromosome 21 and presents with all or some of the following features:

- Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Adrenal failure

- Gonadal failure

- Vitiligo

- Alopecia

- Hypothyroidism

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- Pernicious anemia

- Steatorrhea

Type 2 PGAD (Schmidt syndrome; OMIM 269200) consists of type 1 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroid disease, and adrenal failure. Individuals with this condition generally present in the second or third decades of life, although some components of the syndrome may be present in the pediatric age group. Type 2 PGAD is transmitted as an autosomal disorder with variable penetrance. Adrenal insufficiency should be considered in patients with type 1 diabetes and unexplained fatigue, hypotension, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia and hyperkalemia.

Other acquired causes of adrenal failure include the following:

- Adrenal hemorrhage [18]

- Infections (eg, tuberculosis [TB], human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection)

- Neoplastic destruction

- Metabolic disorders (eg, various forms of adrenal leukodystrophy [OMIM 300100], [19, 20] Wolman disease [OMIM 278000], Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome [OMIM 270400] [21, 22] )

- Ketoconazole and related antifungals, as well as the anesthetic etomidate, can inhibit steroid synthesis, causing adrenal insufficiency [23, 13, 24]

- Mitotane, an agent used to treat adrenal carcinoma, results in adrenal insufficiency, due to direct toxic effects on the adrenal cortex [25]

Hemochromatosis may cause either primary (hereditary form OMIM 235200) or secondary adrenal insufficiency. Among patients with thalassemia or other forms of anemia who have received multiple transfusions, iron deposition in the pituitary and/or adrenal glands may also cause adrenal insufficiency.

Congenital primary adrenal insufficiency

Congenital Addison disease may occur as a result of adrenal hypoplasia [26, 27, 28] or hyperplasia.

Inherited as an X-linked disorder, adrenal hypoplasia congenita (OMIM 300200)—caused by deletion or mutation of the gene DAX1/NR0B1 (which encodes for the nuclear receptor DAX1) on chromosome Xp21.2—is additionally associated with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism and primary defects in sperm production. [29] There is often a contiguous gene deletion that also involves the genes for glycerol kinase deficiency and dystrophin, resulting in elevations in serum glycerol (often measured using a triglyceride assay) and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Deletion or mutation of the gene NR5A1, which encodes for the nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1, also results in congenital adrenal hypoplasia and may cause XY gonadal dysgenesis. [13] An alternate form of adrenal hypoplasia congenita, non-X linked, is characterized by intrauterine growth retardation and skeletal and genital anomalies (ie, IMAGe syndrome) (OMIM 614732). Still another type of adrenal hypoplasia congenita, an autosomal recessive form of uncertain etiology, has also been described (OMIM 240200).

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia results from a deficiency of one of several enzymes required for adrenal synthesis of cortisol. Symptoms of adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease) most often develop with combined deficiencies of cortisol and aldosterone. The most prevalent form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia is caused by a deficiency in steroid 21-hydroxylase (OMIM 201910).

Lipoid adrenal hyperplasia, another rare form of adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease), is caused by a mutation in the steroid acute regulatory protein (ie, STAR protein) (OMIM 201710) [30] or a mutation in the cholesterol side-chain cleavage gene (at the cytochrome P450 [CYP] 11A locus) (OMIM 118485). [31] This disease causes a defective synthesis of all adrenocortical hormones. In its complete form, the disease is lethal.

Mutations or deletions involving CYP oxidoreductase, a flavoprotein that provides electrons to various enzyme systems, results in combined deficiencies of 17-hydroxylase, 21-hydroxylase, and 17-20 lyase activities. The result is adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease), which is often accompanied by skeletal dysplasia, genital anomalies, and primary hypogonadism (OMIM 613571). [32, 33, 34]

Relative adrenal insufficiency

The term relative adrenal insufficiency has been coined to describe patients with critical illness who do not appear to mount the cortisol response expected given the severity of their illness.

Some patients developed adrenal insufficiency after exposure to etomidate, an agent known to interfere with cortisol synthesis. [35] Early reports indicated improvements in outcome when such patients were provided with glucocorticoids at stress doses. Subsequent studies have clearly confirmed the fact that a substantial number of patients with critical illness who have not been exposed to etomidate have low serum cortisol concentrations. [36] Some studies have found that those with very high concentrations of cortisol have a worse prognosis and a higher complication rate of secondary sepsis or intestinal perforation. Controlled trials in adults have failed to confirm the benefit of glucocorticoid replacement therapy.

Among critically ill children, a low incremental cortisol response to ACTH does not predict mortality. [37] There is still much controversy regarding how to best diagnose adrenal insufficiency in hospitalized children and adults, as well as whether and when to treat. Thus, the decision to treat a critically ill patient with glucocorticoids must be made on a case-by-case basis until further definitive evidence is available. [38]

Epidemiology

Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease) is uncommon in the United States. By comparison, iatrogenic central adrenal insufficiency is a more frequent cause of morbidity and mortality, although its exact incidence is unknown. Retrospective case review in one US urban center suggests that the prevalence of adrenal insufficiency in childhood is higher than previously suspected, approximately equivalent to that of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. [39] Adrenal insufficiency secondary to congenital adrenal hyperplasia occurs in approximately 1 per 16,000 infants.

Willis and Vince collected data from Coventry County, Great Britain, where the prevalence of adrenal insufficiency was similarly reported as 110 cases per million persons of all ages. [40] More than 90% of cases have been attributed to autoimmune disease. An Italian study provided statistics comparable to those observed in Great Britain: [41] an estimated 117 cases per million persons. A study by Olafsson and Sigurjonsdottir estimated the prevalence of primary adrenal insufficiency in Iceland to be 22.1 per 100,000 population. [42]

Worldwide, the most common cause of adrenal insufficiency is tuberculosis (TB), with a calculated incidence of this condition caused by TB at approximately 5-6 cases per million persons per year.

Although there does not appear to be a racial predilection, sex and age-related differences have been observed. Autoimmune adrenal insufficiency is more common in female individuals than in male individuals and in adults than children, whereas adrenal insufficiency due to adrenoleukodystrophy is limited to male individuals, because it is X linked.

A form of congenital adrenal hypoplasia due to a defect in DAX1/NR0B1 is also X-linked and, therefore, is confined to males. Secondary forms of adrenal insufficiency such as those due to a deficiency of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) or corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), or a defect in the ACTH receptor, are equally common among male and female individuals.

Congenital causes, such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia, congenital adrenal hypoplasia, and defects in the ACTH receptor, most commonly become apparent in childhood.

Prognosis

With proper treatment and compliance, patients with adrenal insufficiency can live a normal life span without limitations. However, the prognosis for an untreated patient with adrenal insufficiency is poor. Some studies have found that those with very high concentrations of cortisol have a worse prognosis and a higher complication rate of secondary sepsis or intestinal perforation.

Death is a common outcome, usually from hypotension or cardiac arrhythmia secondary to hyperkalemia, unless replacement steroid therapy is begun.

A nationwide Swedish study, by Chantzichristos et al, indicated that the mortality risk is higher in patients with both diabetes mellitus and adrenal insufficiency than in those with diabetes alone. Among the diabetes/adrenal insufficiency patients, the mortality rate was 28%, compared with 10% in patients with just diabetes, with the estimated relative risk increase in overall mortality being 3.89 for the diabetes/adrenal insufficiency group compared with the diabetes patients. Although mortality in both groups most commonly resulted from cardiovascular problems, the death rate from diabetes complications, infectious diseases, and unknown causes was higher in the diabetes/adrenal insufficiency group than in the controls with diabetes. [43]

Complications

Hypotension, shock, hypoglycemia, and death are the primary complications of adrenal insufficiency. [44] In addition, daily oral glucocorticoid therapy may provide iatrogenic suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis within 2 weeks. Effects can last for weeks to months, depending on the duration of exposure to pharmacologic doses of glucocorticoids. Complications of excessive glucocorticoids include the following:

- Growth failure

- Obesity

- Striae

- Osteoporosis

- Muscle weakness

- Hypertension

- Hyperglycemia

- Cataracts

Complications of excessive administration of mineralocorticoids include hypertension and hypokalemia.

A prospective, multicenter study by Hosokawa et al indicated that the rate of adrenal crisis occurring in pediatric adrenal insufficiency is substantial, at 4.27 per 100 person-years. At enrollment, patients in the study had a median age of 14.3 years, with the investigators reporting that younger age at enrollment was an independent risk factor for adrenal crisis. An increased number of infections was an independent risk factor as well. [45]

Patient Education

Educate patients with adrenal insufficiency and their caretakers about the consequences and potential for death if adequate replacement therapy is not provided.

Advise patients and their caretakers to immediately seek medical help if the patient becomes ill. Patients should wear or carry a medical alert tag or card at all times to help them receive appropriate emergency care if they are found unconscious.

Supplemental and injectable glucocorticoid

Patients and their caretakers should know how to administer supplemental glucocorticoid in times of illness or traumatic stress. Include education about how to administer an injectable glucocorticoid when the patient is vomiting or unable to take oral stress doses. Periodically reinforce this information, because caretakers are often reluctant to inject medications.

An intramuscular injection of hydrocortisone (eg, 25 mg for infants, 50 mg for children, 100 mg for adults) can be lifesaving in the interval before the patient receives professional medical care. If this injection is not possible, rectal hydrocortisone can be used until systemic glucocorticoids can be administered.

- Guran T. Latest Insights on the Etiology and Management of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency in Children. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017 Dec 30. 9 (Suppl 2):9-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Munir S, Quintanilla Rodriguez BS, Waseem M. Addison Disease. StatPearls. 2024 Jan 30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lashansky G, Saenger P, Fishman K, Gautier T, Mayes D, Berg G. Normative data for adrenal steroidogenesis in a healthy pediatric population: age- and sex-related changes after adrenocorticotropin stimulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991 Sep. 73(3):674-86. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Neary N, Nieman L. Adrenal insufficiency: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010 Apr 6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Feb 10. 101 (2):364-89. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Heckmann M, Hartmann MF, Kampschulte B, Gack H, Bodeker RH, Gortner L. Cortisol production rates in preterm infants in relation to growth and illness: a noninvasive prospective study using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Oct. 90(10):5737-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Stewart, PM. The adrenal cortex. Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen RP, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2008. Chapter 14.

- Allen DB. Effects of inhaled steroids on growth, bone metabolism, and adrenal function. Adv Pediatr. 2006. 53:101-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Orme LM, Bond JD, Humphrey MS, Zacharin MR, Downie PA, Jamsen KM. Megestrol acetate in pediatric oncology patients may lead to severe, symptomatic adrenal suppression. Cancer. 2003 Jul 15. 98(2):397-405. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gibb FW, Stewart A, Walker BR, Strachan MW. Adrenal insufficiency in patients on long-term opioid analgesia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016 Jun 4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Josephsen JB, Hemmann BM, Anderson CD, et al. Presumed adrenal insufficiency in neonates treated with corticosteroids for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol. 2021 Nov 1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tsigos C, Arai K, Hung W, Chrousos GP. Hereditary isolated glucocorticoid deficiency is associated with abnormalities of the adrenocorticotropin receptor gene. J Clin Invest. 1993 Nov. 92(5):2458-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lavin N, ed. Manual of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Clark A, Weber A. Molecular insights into inherited ACTH resistance syndromes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1994. 5:209-14. [Full Text].

- Handschug K, Sperling S, Yoon SJ, Hennig S, Clark AJ, Huebner A. Triple A syndrome is caused by mutations in AAAS, a new WD-repeat protein gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2001 Feb 1. 10(3):283-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Grant DB, Barnes ND, Dumic M, Ginalska-Malinowska M, Milla PJ, von Petrykowski W. Neurological and adrenal dysfunction in the adrenal insufficiency/alacrima/achalasia (3A) syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1993 Jun. 68(6):779-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Perry R, Kecha O, Paquette J, Huot C, Van Vliet G, Deal C. Primary adrenal insufficiency in children: twenty years experience at the Sainte-Justine Hospital, Montreal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jun. 90(6):3243-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Purandare A, Godil MA, Prakash D, Parker R, Zerah M, Wilson TA. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage associated with transient antiphospholipid antibody in a child. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2001 Jun. 40(6):347-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Laureti S, Casucci G, Santeusanio F, Angeletti G, Aubourg P, Brunetti P. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy is a frequent cause of idiopathic Addison's disease in young adult male patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996 Feb. 81(2):470-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Korenke GC, Roth C, Krasemann E, Hufner M, Hunneman DH, Hanefeld F. Variability of endocrinological dysfunction in 55 patients with X-linked adrenoleucodystrophy: clinical, laboratory and genetic findings. Eur J Endocrinol. 1997 Jul. 137(1):40-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Andersson HC, Frentz J, Martínez JE, Tuck-Muller CM, Bellizaire J. Adrenal insufficiency in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1999 Feb 19. 82(5):382-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nowaczyk MJM, Wassif CA, Adam MP, et al. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. GeneReviews. Updated 2020 Jan 30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Loose DS, Kan PB, Hirst MA, Marcus RA, Feldman D. Ketoconazole blocks adrenal steroidogenesis by inhibiting cytochrome P450-dependent enzymes. J Clin Invest. 1983 May. 71 (5):1495-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Reimondo G, Puglisi S, Zaggia B, et al. Effects of mitotane on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with adrenocortical carcinoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017 Oct. 177 (4):361-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Storr HL, Mitchell H, Swords FM, et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and molecular studies in paediatric Cushing's syndrome due to primary nodular adrenocortical hyperplasia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004 Nov. 61 (5):553-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Peter M, Viemann M, Partsch CJ, Sippell WG. Congenital adrenal hypoplasia: clinical spectrum, experience with hormonal diagnosis, and report on new point mutations of the DAX-1 gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Aug. 83(8):2666-74. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ferraz-de-Souza B, Achermann JC. Disorders of adrenal development. Endocr Dev. 2008. 13:19-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kempna P, Fluck CE. Adrenal gland development and defects. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Feb. 22(1):77-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lalli E, Sassone-Corsi P. DAX-1 and the adrenal cortex. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1999. 6:185-90. [Full Text].

- Baker BY, Lin L, Kim CJ, et al. Nonclassic congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia: a new disorder of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein with very late presentation and normal male genitalia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Dec. 91(12):4781-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kim CJ, Lin L, Huang N, et al. Severe combined adrenal and gonadal deficiency caused by novel mutations in the cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme, P450scc. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Mar. 93(3):696-702. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Miller WL. Minireview: regulation of steroidogenesis by electron transfer. Endocrinology. 2005 Jun. 146(6):2544-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pandey AV, Fluck CE, Huang N, Tajima T, Fujieda K, Miller WL. P450 oxidoreductase deficiency: a new disorder of steroidogenesis affecting all microsomal P450 enzymes. Endocr Res. 2004 Nov. 30(4):881-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fluck CE, Tajima T, Pandey AV, Arlt W, Okuhara K, Verge CF. Mutant P450 oxidoreductase causes disordered steroidogenesis with and without Antley-Bixler syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004 Mar. 36(3):228-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vinclair M, Broux C, Faure P, et al. Duration of adrenal inhibition following a single dose of etomidate in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008 Apr. 34(4):714-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lamberts SW, Bruining HA, de Jong FH. Corticosteroid therapy in severe illness. N Engl J Med. 1997 Oct 30. 337(18):1285-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pizarro CF, Troster EJ, Damiani D, Carcillo JA. Absolute and relative adrenal insufficiency in children with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2005 Apr. 33(4):855-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fleseriu M, Loriaux DL. "Relative" adrenal insufficiency in critical illness. Endocr Pract. 2009 Sep-Oct. 15(6):632-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hsieh S, White PC. Presentation of primary adrenal insufficiency in childhood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jun. 96(6):E925-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Willis AC, Vince FP. The prevalence of Addison's disease in Coventry, UK. Postgrad Med J. 1997 May. 73(859):286-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Laureti S, Vecchi L, Santeusanio F, Falorni A. Is the prevalence of Addison's disease underestimated? [letter]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999 May. 84(5):1762. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Olafsson AS, Sigurjonsdottir HA. Increasing prevalence of Addison disease: results from a nationwide study. Endocr Pract. 2016 Jan. 22 (1):30-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chantzichristos D, Persson A, Eliasson B, et al. Mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus and Addison's disease: a nationwide, matched, observational cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017 Jan. 176 (1):31-39. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kamrath C. Beyond the adrenals: Organ manifestations in inherited primary adrenal insufficiency in children. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020 Mar. 182 (3):C9-C12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hosokawa M, Ichihashi Y, Sato Y, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Adrenal Crisis in Pediatric-onset Adrenal Insufficiency: A Prospective Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023 Dec 21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Arlt W, Allolio B. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2003 May 31. 361(9372):1881-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Besser GM, Thorner MO. Adrenal insufficiency. Clinical Endocrinology. St Louis, Mo: Mosby-Year Book; 1996. [CD-ROM]:

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008 Jan. 36(1):296-327. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Clark L, Preissig C, Rigby MR, Bowyer F. Endocrine issues in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008 Jun. 55(3):805-33, xiii. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kamoi K, Tamura T, Tanaka K, Ishibashi M, Yamaji T. Hyponatremia and osmoregulation of thirst and vasopressin secretion in patients with adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993 Dec. 77(6):1584-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Dickstein G. Commentary to the article: comparison of low and high dose corticotropin stimulation tests in patients with pituitary disease [letter]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Dec. 83(12):4531-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lavin N, ed. Manual of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Wolters Kluwer; 2019.

- Chao CS, Shi RZ, Kumar RB, Aye T. Salivary cortisol levels by tandem mass spectrometry during high dose ACTH stimulation test for adrenal insufficiency in children. Endocrine. 2020 Jan. 67 (1):190-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ciancia S, van den Berg SAA, van den Akker ELT. The Reliability of Salivary Cortisol Compared to Serum Cortisol for Diagnosing Adrenal Insufficiency with the Gold Standard ACTH Stimulation Test in Children. Children (Basel). 2023 Sep 19. 10 (9):[QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larson PR, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2008. 229.

- Iwanaga K, Yamamoto A, Matsukura T, Niwa F, Kawai M. Corticotrophin-releasing hormone stimulation tests for the infants with relative adrenal insufficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017 Dec. 87 (6):660-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kazlauskaite R, Evans AT, Villabona CV, et al. Corticotropin tests for hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal insufficiency: a metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Nov. 93(11):4245-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Thaler LM. Comment on the low-dose corticotropin stimulation test is more sensitive than the high-dose test. [letter]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Dec. 83(12):4530-1; author reply 4532-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tordjman K, Jaffe A, Greenman Y, Stern N. Comments on the comparison of low and high dose corticotropin stimulation tests in patients with pituitary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Dec. 83(12):4530; author reply 4532-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mayenknecht J, Diederich S, Bahr V, Plockinger U, Oelkers W. Comparison of low and high dose corticotropin stimulation tests in patients with pituitary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 May. 83(5):1558-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Neary N, Nieman L. Adrenal insufficiency: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010 Jun. 17(3):217-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Libe R, Barbetta L, Dall'Asta C, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation on hormonal, metabolic and behavioral status in patients with hypoadrenalism. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004 Sep. 27(8):736-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- van Thiel SW, Romijn JA, Pereira AM, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrostenedione, superimposed on growth hormone substitution, on quality of life and insulin-like growth factor I in patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency: a randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jun. 90(6):3295-303. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Quinkler M, Ekman B, Marelli C, et al. Prednisolone is associated with a worse lipid profile than hydrocortisone in patients with adrenal insufficiency. Endocr Connect. 2017 Jan. 6 (1):1-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Chandy DD, Bhatia E. Bone mineral density in patients with Addison disease on replacement therapy with prednisolone. Endocr Pract. 2016 Apr. 22 (4):434-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Merke DP, Chrousos GP, Eisenhofer G, et al. Adrenomedullary dysplasia and hypofunction in patients with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2000 Nov 9. 343(19):1362-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Coutant R, Maurey H, Rouleau S, et al. Defect in epinephrine production in children with craniopharyngioma: functional or organic origin?. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Dec. 88(12):5969-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Frank GR, Speiser PW, Griffin KJ, Stratakis CA. Safety of medications and hormones used in pediatric endocrinology: adrenal. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2004 Nov. 2 Suppl 1:134-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Specialty Editor Board

Mary L Windle, PharmD Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Barry B Bercu, MD Professor, Departments of Pediatrics, Molecular Pharmacology and Physiology, University of South Florida College of Medicine, All Children's Hospital

Barry B Bercu, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, American Medical Association, American Pediatric Society, Association of Clinical Scientists, Endocrine Society, Florida Medical Association, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Society for Pediatric Research, Southern Society for Pediatric Research, Society for the Study of Reproduction, American Federation for Clinical Research, Pituitary Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Sasigarn A Bowden, MD, FAAP Professor of Pediatrics, Section of Pediatric Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, Department of Pediatrics, Ohio State University College of Medicine; Pediatric Endocrinologist, Division of Endocrinology, Nationwide Children’s Hospital; Affiliate Faculty/Principal Investigator, Center for Clinical Translational Research, Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital

Sasigarn A Bowden, MD, FAAP is a member of the following medical societies: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, Central Ohio Pediatric Society, Endocrine Society, International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Society for Pediatric Research

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Karl S Roth, MD Retired Professor and Chair, Department of Pediatrics, Creighton University School of Medicine

Karl S Roth, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Nutrition, American Pediatric Society, American Society for Nutrition, American Society of Nephrology, Association of American Medical Colleges, Medical Society of Virginia, New York Academy of Sciences, Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society, Society for Pediatric Research, Southern Society for Pediatric Research

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Thomas A Wilson, MD Professor of Clinical Pediatrics, Chief and Program Director, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, Department of Pediatrics, The School of Medicine at Stony Brook University Medical Center

Thomas A Wilson, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Endocrine Society, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Phi Beta Kappa

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.