Cyclosporiasis: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology (original) (raw)

Overview

Practice Essentials

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an intestinal coccidia that infects the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. This organism was first described in human feces in 1979. Since the advent of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic, C cayetanensis has been increasingly recognized as an enteric pathogen. [1]

Cyclospora species are ubiquitous and infect a variety of animals, birds and reptiles. Humans are the only known hosts of C cayetanensis.

Causes of cyclosporiasis include consumption of infected water or produce or exposure to the organism during travel to countries where it is endemic. Immunosuppression is a risk factor for chronic cyclosporiasis in endemic areas or among travelers to these areas. [2]

Discuss proper food and water precautions needed with patients who are traveling to endemic regions to prevent this and other infections transmitted through the fecal-oral route.

Pathophysiology

Cyclospora species are variably acid-fast, round-to-ovoid organisms that measure 8-10 µm in diameter. Cyclospora species exogenously sporulate and have 2 sporocysts per oocyst. Transmission follows ingestion of oocysts in fecally contaminated water or produce. Direct person-to-person transmission is considered unlikely because the oocysts are not infectious when excreted; the oocysts undergo sporulation outside the human host before becoming infective. The median incubation period is 1 week, during which time the organism invades enterocytes of the small intestine.

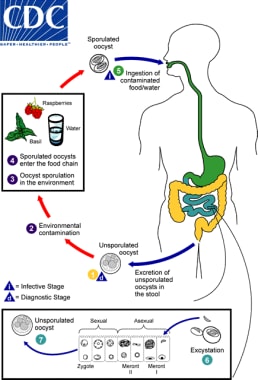

Life cycle of Cyclospora. (1) When freshly passed in stools, the oocyst is not infective; thus, direct fecal-oral transmission cannot occur and this differentiates Cyclospora from another important coccidian parasite, Cryptosporidium. (2) In the environment, sporulation occurs after days or weeks at temperatures between 22°C to 32°C, resulting in division of the sporont into two sporocysts, each containing two elongate sporozoites (3). Fresh produce and water can serve as vehicles for transmission (4) and the sporulated oocysts are then ingested in contaminated food or water (5). The oocysts exist in the gastrointestinal tract, freeing the sporozoites which invade the epithelial cells of the small intestine (6). Inside the cells, they undergo asexual multiplication and sexual development to mature into oocysts which will be shed in stools (7). The potential mechanisms of contamination of food and water are still under investigation. Courtesy of the CDC (https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp).

Cyclospora species are characterized by an anterior polar complex that allows penetration into host cells, but the life cycle of the parasite and the mechanisms by which it interacts with human host target cells to cause disease are poorly understood.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The prevalence of infection in endemic areas is estimated at 2% to 18% (including asymptomatic and symptomatic infections) and for developed countries prevalence is estimated at 0.1% to 0.5%). [3] Cases in the developed countries are usually associated with outbreaks from recognized contaminated food and water.

The first known outbreak of cyclosporiasis in the United States occurred in 1990 in a Chicago hospital's physicians' dormitory and was attributed to an infected water source. [4, 5] Since then, multiple US epidemics of cyclosporiasis have been reported and have been attributed to infected Guatemalan raspberries [6, 7] basil, mesclun lettuce, [8, 9, 10, 11] imported Thai basil, [12] and snow peas. [13] Outbreaks in 2013 were reported in Texas related to infected cilantro and cases in Iowa and Nebraska related to contaminated salad mix. [14] Cyclosporiasis has also been reported as a cause of foodborne diarrhea in outbreaks due to domestic contamination from vegetable trays and precut salad mixes and produce such as romaine lettuce and green onions. [15, 16, 17] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) monitors the occurrence of cyclosporiasis in the United States and is a notifiable disease.

In August 2014, CDC was notified of 304 ill persons with confirmed Cyclospora infection in 2014. About 64% of cases were reported from Texas and 64% were reported in July 2014. Preliminary investigation linked cases in Texas with cilantro from Mexico; however, none of the cases outside Texas were linked to cilantro.

In August 2017, the CDC issued a Health Alert Network advisory following an increase in reported cases of cyclosporiasis. The advisory guides providers to consider a diagnosis of cyclosporiasis in patients who experience prolonged or remitting-relapsing diarrhea. Between May 1, 2017, and August 2, 2017, 206 cases of Cyclospora infections were reported to the CDC from 27 states. Eighteen cases required hospitalization; however, no deaths were reported. [18]

A decrease in the incidence of cyclosporiasis was reported in the United States (34 states reporting infections) from May to early August 2020 (1241 cases vs 2408 cases during the same period in 2019). US cases have typically increased in recent years; thus, this decrease may reflect the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. [15]

International statistics

Worldwide, most fecal isolates have been obtained from residents of developing countries or from travelers returning from these regions. [19, 20] Cyclosporiasis is endemic in Haiti, Nepal, and Peru, with a strong seasonal predominance during rainy spring and summer months. Cyclosporiasis has also been reported in travelers returning from Mexico, Southeast Asia, Puerto Rico, Indonesia, [21] Morocco, Pakistan, and India. Cases have also been recognized in Kuwait [22] and China. [23]

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

No racial predilection has been reported.

Cyclosporiasis equally affects both genders.

Persons of all ages can be affected, although cyclosporiasis primarily affects children in developing countries where the disease is endemic.

Prognosis

Because infection is self-limited in the immunocompetent host, full recovery is expected. With treatment and prophylaxis to prevent relapses, infection in the immunocompromised host can generally be controlled.

Morbidity/mortality

Death is exceptionally rare. Very little morbidity results from this infection, except in persons with underlying immunosuppression, in whom chronic diarrhea can develop, resulting in weight loss and malabsorption.

- Mannheimer SB, Soave R. Protozoal infections in patients with AIDS. Cryptosporidiosis, isosporiasis, cyclosporiasis, and microsporidiosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994 Jun. 8(2):483-98. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Stark D, Barratt JL, van Hal S, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis JT. Clinical significance of enteric protozoa in the immunosuppressed human population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009 Oct. 22(4):634-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Murray P, Rosenthal K, Pfaller M. Intestinal and Urogenital protozoa. Medical Microbiology. 7th edition. 2013. 745-758.

- Huang P, Weber JT, Sosin DM, Griffin PM, Long EG, Murphy JJ, et al. The first reported outbreak of diarrheal illness associated with Cyclospora in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Sep 15. 123(6):409-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Carter RJ, Guido F, Jacquette G, Rapoport M. Outbreak of cyclosporiasis at a country club -- New York, 1995. : 45th Annual Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) Conference. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service April 1996:58;

- Herwaldt BL, Ackers ML. An outbreak in 1996 of cyclosporiasis associated with imported raspberries. The Cyclospora Working Group. N Engl J Med. 1997 May 29. 336(22):1548-56. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ho AY, Lopez AS, Eberhart MG, et al. Outbreak of cyclosporiasis associated with imported raspberries, Philadelphia, pennsylvania, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002 Aug. 8(8):783-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- CDC. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks of cyclosporiasis--United States, 1997. JAMA. 1997 Jun 11. 277(22):1754. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- CDC. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: outbreaks of cyclosporiasis--1997. JAMA. 1997 Jul 9. 278(2):108. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- CDC. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: outbreaks of cyclosporiasis--United States, 1997. JAMA. 1997 Jun 18. 277(23):1838. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- CDC. From the Centers for Disease Control. Outbreak of cyclosporiasis-- Northern Virginia-Washington, DC-Baltimore, Maryland, metropolitan area, 1997. JAMA. 1997 Aug 20. 278(7):538-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hoang LM, Fyfe M, Ong C, et al. Outbreak of cyclosporiasis in British Columbia associated with imported Thai basil. Epidemiol Infect. 2005 Feb. 133(1):23-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Heilpern KL, Wald M. Update on emerging infections: news from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of cyclosporiasis associated with snow peas--Pennsylvania, 2004. Ann Emerg Med. 2005 May. 45(5):529-31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). outbreaks of cyclosporiasis--United States, June-August 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Nov 1. 62(43):862. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- CDC. Parasites - Cyclosporiasis (Cyclospora Infection). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/index.html. 2021 Aug 26; Accessed: November 10, 2022.

- Almeria S, Shipley A. Detection of Cyclospora cayetanensis on bagged pre-cut salad mixes within their shelf-life and after sell by date by the U.S. food and drug administration validated method. Food Microbiol. 2021 Sep. 98:103802. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hall NB, Chancey RJ, Keaton AA, et al. Cyclosporiasis Epidemiologically Linked to Consumption of Green Onions: Houston Metropolitan Area, August 2017. J Food Prot. 2020 Jan 21. 326-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Increase in Reported cases of Cyclospora cayetanensis Infection, United States, Summer 2017. CDC Health Alert Network. Available at https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00405.asp. August 07, 2017; Accessed: August 8, 2017.

- Chacin-Bonilla L. Epidemiology of Cyclospora cayetanensis: A review focusing in endemic areas. Acta Trop. 2010 Sep. 115(3):181-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Samie A, Guerrant RL, Barrett L, Bessong PO, Igumbor EO, Obi CL. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic and bacterial pathogens in diarrhoeal and non-diarroeal human stools from Vhembe district, South Africa. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009 Dec. 27(6):739-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Blans MC, Ridwan BU, Verweij JJ, et al. Cyclosporiasis outbreak, Indonesia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005 Sep. 11(9):1453-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Iqbal J, Hira PR, Al-Ali F, Khalid N. Cyclospora cayetanensis: first report of imported and autochthonous infections in Kuwait. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011 May 28. 5(5):383-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zhou Y, Lv B, Wang Q, Wang R, Jian F, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cyclospora cayetanensis, Henan, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Oct. 17(10):1887-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Sifuentes-Osornio J, Porras-Cortés G, Bendall RP, Morales-Villarreal F, Reyes-Terán G, Ruiz-Palacios GM. Cyclospora cayetanensis infection in patients with and without AIDS: biliary disease as another clinical manifestation. Clin Infect Dis. 1995 Nov. 21(5):1092-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zar FA, El-Bayoumi E, Yungbluth MM. Histologic proof of acalculous cholecystitis due to Cyclospora cayetanensis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001 Dec 15. 33(12):E140-1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- de Górgolas M, Fortés J, Fernández Guerrero ML. Cyclospora cayetanensis Cholecystitis in a patient with AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Jan 16. 134(2):166. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Richardson RF Jr, Remler BF, Katirji B, Murad MH. Guillain-Barré syndrome after Cyclospora infection. Muscle Nerve. 1998 May. 21(5):669-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Connor BA, Johnson EJ, Soave R. Reiter syndrome following protracted symptoms of Cyclospora infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001 May-Jun. 7(3):453-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Kovacs-Nace E, Wallace S, Eberhard ML. Uniform staining of Cyclospora oocysts in fecal smears by a modified safranin technique with microwave heating. J Clin Microbiol. 1997 Mar. 35(3):730-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- McHardy IH, Wu M, Shimizu-Cohen R, Couturier MR, Humphries RM. Detection of intestinal protozoa in the clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2014 Mar. 52(3):712-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Bourée P, Lancon A, Bisaro F, Bonnot G. Six human cyclosporiasis: with general review. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2007 Aug. 37(2):349-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Verdier RI, Fitzgerald DW, Johnson WD Jr, Pape JW. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole compared with ciprofloxacin for treatment and prophylaxis of Isospora belli and Cyclospora cayetanensis infection in HIV-infected patients. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Jun 6. 132(11):885-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Diaz E, Mondragon J, Ramirez E, Bernal R. Epidemiology and control of intestinal parasites with nitazoxanide in children in Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003 Apr. 68(4):384-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Life cycle of Cyclospora. (1) When freshly passed in stools, the oocyst is not infective; thus, direct fecal-oral transmission cannot occur and this differentiates Cyclospora from another important coccidian parasite, Cryptosporidium. (2) In the environment, sporulation occurs after days or weeks at temperatures between 22°C to 32°C, resulting in division of the sporont into two sporocysts, each containing two elongate sporozoites (3). Fresh produce and water can serve as vehicles for transmission (4) and the sporulated oocysts are then ingested in contaminated food or water (5). The oocysts exist in the gastrointestinal tract, freeing the sporozoites which invade the epithelial cells of the small intestine (6). Inside the cells, they undergo asexual multiplication and sexual development to mature into oocysts which will be shed in stools (7). The potential mechanisms of contamination of food and water are still under investigation. Courtesy of the CDC (https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp).

- Oocysts of C cayetanensis stained with modified acid-fast stain. Note the variability of staining in the four oocysts. Courtesy of the CDC (https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp).

- Oocyst of C cayetanensis viewed under UV microscopy. Courtesy of the CDC (https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp).

Author

Coauthor(s)

Jocelyn Y Ang, MD, FAAP, FIDSA, FPIDS Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, Wayne State University School of Medicine; Professor of Pediatrics, Central Michigan University College of Medicine; Consulting Staff, Division of Infectious Diseases, Children's Hospital of Michigan

Jocelyn Y Ang, MD, FAAP, FIDSA, FPIDS is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Specialty Editor Board

Mary L Windle, PharmD Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Russell W Steele, MD Clinical Professor, Tulane University School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Ochsner Clinic Foundation

Russell W Steele, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Immunologists, American Pediatric Society, American Society for Microbiology, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Louisiana State Medical Society, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, Society for Pediatric Research, Southern Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Michael D Nissen, MBBS FRACP, FRCPA, Associate Professor in Biomolecular, Biomedical Science & Health, Griffith University; Director of Infectious Diseases and Unit Head of Queensland Paediatric Infectious Laboratory, Sir Albert Sakzewski Viral Research Centre, Royal Children's Hospital

Michael D Nissen, MBBS is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia, Royal Australasian College of Physicians, American Society for Microbiology, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Cathy Jo Schroeder, RN, MSN, APN-C Family Nurse Practitioner for James A Boozan MD, Otolaryngologist

Cathy Jo Schroeder, RN, MSN, APN-C is a member of the following medical societies: American Nurses Association and Sigma Theta Tau International

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.