Émile Rey (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Italian mountain guide and mountaineer (1846-1895)

Émile Rey

|

|

|---|---|

| Personal information | |

| Born | August 1846La Saxe, Courmayeur, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Died | 24 August 1895(1895-08-24) (aged 48–49)Dent du Géant, France |

| Occupation(s) | Mountain guide, joiner, carpenter |

| Climbing career | |

| Known for | First ascents around Courmayeur |

| First ascents | Aiguille Noire de Peuterey, Peuterey Ridge, Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey, Aiguille de Talèfre |

| Updated on 19 December 2015 |

Émile Rey (August 1846 — 24 August 1895) was an alpine mountain guide from Aosta Valley in Italy. Dubbed "the Prince of Guides" in Courmayeur, he was one of the most renowned guides at the end of the 19th century, making many first ascents on some of the highest and most difficult mountains in the Mont Blanc massif of the Alps.[1] He has been described as "one of the greatest guides of his generation."[2][3]: 125

Émile Rey was born and lived his life in La Saxe, a small hamlet near Courmayeur.[1] By trade, he was a menuisier (joiner or carpenter), and is known to have contributed to the construction of a number of the alpine huts used at that time by mountaineers to reach more easily the high summits. These huts included the refuges of the Grand Paradis, Col du Géant, Aiguilles Grises and Grandes Jorasses.[4]: 133

Rey's career as a mountain guide did not begin until the "great age of conquest" of the Alps was over. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not learn his craft by serving an apprenticeship with other, older guides. One British mountaineer wrote in detail about Rey's achievements in "Pioneers of the Alps" (1888)[4]: 133

His reputation as one of the first rock-climbers in the Alps, and the position he holds among other guides, are the result of his own aptitude and ability, the great enthusiasm he has for his profession, and the energy and earnestness with which he pursues it.

— C.D. Cunningham 1888

The first offer that Rey received of a long-term engagement as a guide came only after he had reached the age of thirty, when Lord Wentworth retained him for the greater part of the 1876 climbing season, and for the subsequent two seasons. In 1877 they made notable first ascents together of the Aiguille (Noire) de Peuterey, and Les Jumeaux de Valtournanche. However it was with two other clients, J. Baumann and John Oakley Maund, that Rey started to make his name as one of the most skillful and boldest rock-climbers in the Alps. Not all of their attempts at bold new routes were successful, including their attempt at the Aiguille du Plan from the Plan des Aiguilles.[4]: 132

Another unsuccessful, but nevertheless very bold early attempt took place in 1881 when J. Baumann, Rey, and his two fellow guides, Johann Juan and J. Maurer, attempted to climb the Eiger's Mittellegi ridge. They were thwarted by the difficult big step on that ridge which is nowadays adorned with a fixed rope strung from it, and which was finally climbed for the first time in 1925. Referring to their unsuccessful attempt, J. Baumann wrote about his guide's efforts:[4]: 132

Rey alone and unroped succeeded in turning a very difficult overhanging rock, and proceeded along the arete to a point which has never before been reached.

— Baumann on Rey

The Mittellegi ridge on the Eiger

Rey's first major achievement as a mountaineer and guide came in 1877 when he successfully made the first ever ascent of the Aiguille Noire de Peuterey.[5] Thereafter, Mont Blanc became an important venue for his mountaineering exploits, and he had many regular wealthy clients from across Europe, including Elizabeth Hawkins-Whitshed,[3] Paul Güssfeldt[6]: 194 and Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi.[7]

In 1882, Rey was leader of a team that retrieved the bodies of Francis Maitland Balfour and his guide Johann Petrus, who together had attempted to make the first ascent of the Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey. Balfour had invited Rey to join his party, but Rey declined, considering the snow to be in a dangerous condition.[8] It was to be another three years later before Rey was involved in the first successful attempt to reach its summit.[5]: 133

Commenting in the Alpine Journal on the series of audacious first ascents and new routes that had recently taken place on the Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey, the soldier and mountaineer, J. P. Farrar, who was later to become president of the Alpine Club, noted:[9]

The evolution of these expeditions, among the greatest ever carried out in the Alps, is exceedingly interesting, nor will the names of the greatest guides who rendered their employers such brilliant service be readily forgotten, least of all that of the Italian, Émile Rey, who played such a leading role in the expeditions of 1880, 1885 and 1893.

— J. P. Farrar

Rey was married to Faustina Vercelin[10] and had sons Adolphe and Henri, the eldest, and a grandson, Emile. He was evidently very proud of his children.[11]: 36 Adolphe Rey [fr] (1878–1969) went on to become a mountain guide like his father.

He made more than a dozen first ascents, including:

- 1877: First ascent of the Aiguille Noire de Peuterey with Lord Wentworth (the grandson of Lord Byron) and Jean-Baptiste Bich on 5 August.[12][13]: 89

- 1879: First ascent of the Aiguille de Talèfre (3,730 m) with Johan Baumann, F. J. Cullinan, G. Fitzgerald, Joseph Moser and Laurent Lanier on 25 August.[13]: 189

- 1880: First ascent of the Col de Peuterey with Georg Gruber and Pierre Revel, the Freney, August 13.[14]

- 1882: First ascent of the Calotte de Rochefort, the main summit of Les Périades, with C. D. Cunningham.[4]

- 1883: First ascent of the Lower Peak of the Aiguille du Midi, with C. D. Cunningham.[4]

- 1885: First ascent of the Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey with Henry Seymour King and guides Ambros Supersaxo and Alois Andenmatten on 31 July.[13]: 85

- 1887: First traverse of the Grand Dru to the Petit Dru with Henri Dunod and François Simond on 31 August.[15]: 227

- 1888: First winter traverse of Mont Blanc from the Italian side, with Alessandro, Corradino, Erminio and Vittorio Sella, Joseph Jean-Baptiste and Daniele Maquignaz and Giuseppe Maquignaz and two porters. They went from the Aiguilles Grises, cutting many steps in the Bosses Ridge to reach the summit, and then descended to the Grand Mulets, on 5 January. It was later described as a "very remarkable and daring enterprise".[16]

- 1888: New route to Mont Blanc by the Aiguille de Bionnassay east ridge with Katharine Richardson and Jean-Baptiste Bich on 13 August.[13]: 51

- 1889: First traverse from Petit Dru to the Grand Dru with Katharine Richardson and Jean-Baptiste Bich on 30 August (with assistance from guides positioned at Grand Dru).[15]: 227

- 1890: Castor North Face (in descent) with Katharine Richardson and Jean Baptiste Bich.[6]: 116

- 1893: First ascent of Mont Blanc by the Aiguille Blanche and the Peuterey Ridge with Paul Güssfeldt, Christian Klucker and Cesar Ollier. Four-day climb from 14 to 17 August.[6]: 194

- 1895: Mont Maudit NW Ridge, via Col du Mont Maudit. First climbed (in descent) with George Morse, after a celebratory 50th birthday ascent for Rey of Mont Blanc, on 21 August. He was killed three days later.[6]: 215 [13]: 97

Other significant ascents with which Rey was involved include:

- 1879: Second ascent of the Grand Dru.[17]

- The third, fourth, and fifth ascents of the higher peak of the Dru over four consecutive days. One of these ascents, with W.E. Davidson, was made direct from Montenvert without an overnight stop beforehand. It was also made totally unaided by fixed ropes or ladders, a feat that impressed the first ascensionist, C. T. Dent, who had spent innumerable hours on the route.[4]: 132

- On 16 August 1892 he made the first ascent of the 'variant Güssfeldt', marking the fourth ascent of the Brenva ridge route onto Mont Blanc, with Paul Gussfeldt, Laurent Croux and Michel Savoye. During this ascent Gussfeldt's ice axe fell into the dangerous couloir which nowadays bears his name.[18]

- 1877: First traverse of the Grands Charmoz.[_citation needed_]

- Gran Paradiso from the glacier of the Tribulation.[_citation needed_]

- Dent d'Hérens to the crest Tiefenmatten.[_citation needed_]

In the winter of 1884 Rey travelled to Britain where he spent some weeks with alpine mountaineer C. D. Cunningham in England. His trip included an intellectual afternoon visit to Madame Tussaud's in the company of the editor of the Nineteenth Century literary magazine and a visit to Scotland where on 11 February after a spell of bad weather, Rey, Cunningham and a local man, John Cameron, made a winter ascent to the top of Ben Nevis. At the summit they visited the new observatory which had been opened just a few months earlier, and enjoyed hot steaming coffee and toasted ship's biscuits in the company of the observer and his two assistants.[19] Cunningham later observed that Rey was known to have referred to their trip up Ben Nevis more frequently than some of his other great achievements in the Alps.[4]: 133 Whilst in Scotland Rey also visited Edinburgh where he went to the top of Arthur's Seat, local tradition stating that before doing so he estimated it would take much of the day to achieve.[20]

Rey is known to have spent a winter in Meiringen in order to learn German so that, as a leading guide himself, he would be better equipped to work with some of the top Swiss guides such as Andreas Maurer whose mountaineering skills he much admired. He knew they would constantly come into contact with one another, and that this would better help him work together with the Oberland guide.[4]: 133

Rey was known to have always kept himself fit and in condition. He never smoked and was described as always having a temperate manner in whatever he did, and was always courteous – a characteristic which gained him many acquaintances well beyond the usual climbing circles. In the autumn of 1886 Rey was climbing on the Schreckhorn in the Bernese Oberland and narrowly avoided being killed in an avalanche. However another guided party some ten minutes behind his was struck by falling ice, and their client, a Herr Munz, was killed, and his guide, Meyer, very severely injured, and subsequently died. Rey took the lead in retrieving Munz's body and taking it back down to Grindelwald. One of the alpine climbers who was with Rey, C.D. Cunningham, later wrote how impressed he was with the "great force of character and power of organisation that Rey displayed". He observed how Rey's ability to take the lead without seeming to take command of his fellow guides provided "the moving spirit of the whole party".[4]: 133

Rey has, however, been described as a man who never underestimated his own abilities as a mountain guide, nor did he try to conceal the pride he got from having gained such a good reputation. Writing in 'Pioneers of the Alps (1888) Cunningham, with whom he had made numerous alpine ascents over many years, wrote thus:[4]: 134

He always draws a most distinct line between those of the higher and those of the lower grades in his craft. One morning, at the Montanvert, we were watching the arrival of the 'polyglots,' as an ingenious person once christened that crowd composed of nearly every nationality, who may daily be seen making their toilsome pilgrimage from Chamonix. Among them was an Englishman, who had first provided himself with green spectacles, a veil, and socks to go over his patent leather shoes, and who only wanted a guide to complete his preparations. Going up to Rey, and pointing first to the Mer de Glace, and then to the Chapeau, he inquired "Combiang?" " Voilà, Monsieur," replied Rey, taking off his hat, and indicating with his left hand a group of rather poor specimens of the distinguished Société des Guides, " Voilà les guides pour la Mer de Glace; moi, je suis pour 'la Grande Montagne.'"

— C.D. Cunningham, 1888

Cunningham also noted how willing Rey always was to attend to his clients' needs first, rather than his own, whether more immediate needs in the hut following a long and very tiring day, or in being bold on the rock to ensure they would overcome all difficulties to attain their summit. Despite this determination to succeed, he was always prepared to draw the line "when foolhardiness was about to take the place of courage".[4]: 134

Writing about his life amongst the high alpine summits, Rey once said: "it is not the earnings that push me up to the peaks, it is the great passion I have for the mountains. I have always considered the payment secondary in my life as a guide."[21]

Survival against the odds

[edit]

The Aiguille du Plan from La Flégère, showing the Glacier du Plan descending from its summit

The account below is extracted almost verbatim from True Tales of Mountain Adventure: For Non-Climbers Young and Old (1903):[22]

In August 1880 Émile Rey and Andreas Maurer were guiding an English 'climber', who wanted to reach the summit of the Aiguille du Plan by means of the steep ice slopes [of the Glacier du Plan] above the Chamonix Valley. After step-cutting all day, they reached a point where to go on was impossible, and retreat looked hopeless. To add to their difficulties, bad weather came in with snow and intense cold. They had no alternative but to remain exactly where they were for the night, and, if they survived it, to attempt the descent of the almost precipitous ice-slopes they had with such difficulty ascended. Through the long hours of the bitter night, they stood, roped together, without daring to move, on a narrow ridge, hacked level with their ice-axes. They believed their case was hopeless. Although Andreas Maurer's own back was frozen hard to the ice-wall against which he leaned, and in spite of driving snow and numbing cold, he opened his coat, waistcoat and shirt, and through the long hours of the night he held, pressed against his bare chest, the half-frozen body of the traveller who had urged him to undertake the expedition. The morning broke, still and clear, and at six o'clock, having thawed their stiffened limbs in the warm sun, they commenced the descent. Probably no finer feat in ice-work has ever been performed than that accomplished by Maurer and Rey on that day. Had the bad weather continued, the party could not possibly have descended alive. It then took ten hours of continuous down-climbing on steep ice to reach safety, after eighteen hours of continuous effort without food on the previous day, followed by a night of horrors such as few can realise.

— Mrs Aubrey Le Blond, 1903.

The Dent du Géant

Rey was killed in a fall whilst descending the lower, easy rocks at the base of the Dent du Géant on 24 August 1895 with his client, A. Carson Roberts. They were unroped. Roberts subsequently wrote at very great length and detail about the events, suggested that Rey might have fallen because of some malaise which might have led to a "physical seizure" at an inopportune moment — he previously observed that Rey had not been displaying his usual good form or temperament.[11] Another source later suggested the slip might have been "due to excessive and incorrect hobnailing of his boots".[23]On hearing of Rey's death, Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi was said to have been devastated by the news.[7]Rey was buried in Courmayeur, the form of his gravestone somewhat resembling that of the Dent du Géant, with an ice axe and rope hung over one corner. It bore the following epitaph:

IN MEMORIA DI EMILIO REY

GUIDA ITALIANA VALENTISSIMA

AMATO DEI SUOI ALPINISTI

IN LUNGA SERIA D'IMPRESE

MAESTRO LORO

DI ARDIMENTI DI PRUDENZA

FATALMENTE CADUTO AL DENTE DEL GIGANTE

IL 24 AGOSTO 1895

Amongst the wreaths left at his funeral were those from some of the famous names in the annals of alpine mountaineering, including Katharine Richardson, Paul Güssfeldt and C. D. Cunningham, all of whom had climbed with this guide.[1]: 232 In a short obituary in the Alpine Journal, Güssfeldt described Rey as "the great guide of Courmayeur [whose death] is generally felt as an irreparable loss".[24]

Forty years after Rey's death, mountaineer Frank S. Smythe described him as "the greatest guide of his generation".[2]

The Brouillard ridge, with labels showing the Col Emile Rey and other significant features

The Col Emile Rey (4030 m), located on the Italian side of Mont Blanc (between Mont Brouillard and Picco Luigi Amedeo), is named in Rey's honour.[25] Described as "a superb col in wild surroundings", it can be subject to bad stonefall on both sides. It is not used as a route between adjacent glaciers, but can be used by mountaineers to access the Brouillard Ridge. The first traverse of the Col Émile Rey was made in 1899 by G.B. and G.F. Gugliermina with N. Shiavi, exactly four years to the day after Rey's death.[5]: 125

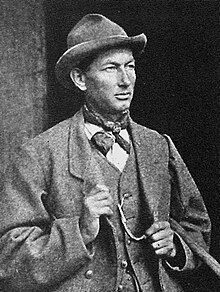

A memorial tablet to Rey, figuring a coiled rope and ice axe, stood in the Piazza Abbé Henry in Courmayeur until at least 1957.[26] It was subsequently replaced with a monument containing a sculpted figure, showing him in a similar pose to that of his photograph, wearing his guide's hat.

It bears the words "Emile Rey, 1846–1895, Prince Des Guides". It stands between monuments to two other alpine guides from Courmayeur, Giuseppe Petigax (1860–1926) and Mario Puchoz (1918–1954).[27][28]

- ^ a b c Gos, Charles (1937). "A Winter's Day at Courmayeur" (PDF). The Alpine Journal. 49–50: 232. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ a b Smythe, Frank (1940). A Mountaineering Holiday: An Outstanding Alpine Climbing Season, 1939 (TBC ed.). TBC. p. ?. ISBN 9781906148867.

- ^ a b The Alpine Club/Royal Geographical Society (October 2011). The Mountaineers. Dorling Kindersley Limited. p. 156. ISBN 978-0241198902.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cunningham, C.D.; Abney, W. de W. (1888). The Pioneers of the Alps (2nd ed.). Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Collomb, Robin (1976). Mont Blanc Range Volume 1. The Alpine Club. p. 133. ISBN 0900523204.

- ^ a b c d Dumler, Helmut; Burkhardt, Willi P. (1994). The High Mountains of the Alps (1st ed.). London: Diadem. ISBN 0898863783.

- ^ a b Tenderini, Mirella; Shandrick, Michael (May 1997). The Duke of the Abruzzi: An Explorer's Life. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0898864992.

- ^ Matthews, Charles Edward (1900). The Annals of Mt Blanc. Boston: L.C.Page & Co. p. 238. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ Jones, H.O. (May 1911). "Some Climbs on the South Side of Mt. Blanc, addendum to". The Alpine Journal. 25 (192): 520.

- ^ "Ritratto di Faustina Vercelin, moglie della famosa guida Emile Rey". dimensionmontagne.org. Dimension Mantagne. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ a b Roberts, A. Carson (May 1936). "Aiguilles: The Tragedy of Emile Rey" (PDF). The Alpine Journal. 48 (252): 38. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Simon (2012) [2010]. Unjustifiable Risk?: The Story of British Climbing. TBC: TBC. ISBN 978-1-85284-627-5.

- ^ a b c d e Griffin, Lindsay (1990). Mont Blanc Massif Volume 1. London: Alpine Club. ISBN 0900523573.

- ^ Chabod, Grivel & Saglio 1963, p. 289

- ^ a b Rébuffat, Gaston (1987) [1962]. Mont-Blanc Jardin féerique + Historique des Ascensions du Mont-Blanc, Établi par Alex Lucchesi (in French). Paris: Denoël. ISBN 2-207-23396-0.

- ^ Russell, C.A. (1988). "One Hundred Years Ago (With extracts from the Alpine Journal)" (PDF). The Alpine Journal: 207–212. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ Russel, C.A. (1979). "One hundred years ago (with extracts from the Alpine Journal)". The Alpine Journal: 204–210.

- ^ Russell, C.A. (1992). "One Hundred Years Ago (with extracts from the Alpine Journal)" (PDF). The Alpine Journal. 97: 240. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Russell, C.A. (1984). "One Hundred Years ago (with extracts from the Alpine Journal)" (PDF). The Alpine Journal: 63. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Graham Brown, T. (1933). "Review of .An Epitome of Fifty Years Climbing" (PDF). The Alpine Journal. 45 (246): 174–178. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Maestri, Cesare. "Alpine Guides: A Story of Love and Responsibility for the Mountains". www.ecodelledolomiti.net. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Le Blond, Mrs Aubrey (1903). True Tales of Mountain Adventure: For Non-Climbers Young and Old. New York: Dutton & Co. pp. 45–46. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ "Untitled article on history of crampons". www.grivel.com. Grivel. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Güssfeldt, Paul (1895). "Correspondence. Emile Rey". Alpine Journal. 17: 568.

- ^ "Col Émile Rey". www.camptocamp.org. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ "Enrico Rey con il figlio Piero davanti al monumento in memoria di Emile Rey". dimensionmontagne.org. Dimension Montagne. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "Emile Rey e Mario Puchoz, Courmayeur". www.flickr.com. Roberto Figueredo Simonetti. 4 July 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "Courmayeur, Giuseppe Petigax & Emile Rey 2015". www.summitpost.org. SummitPost. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Chabod, Renato; Grivel, Lorenzo; Saglio, Silvio (1963). Monte Bianco, vol. I. Guida dei Monti d'Italia. Milano: Club Alpino Italiano e Touring Club Italiano. ISBN 88-365-0063-3.

- Scott, Doug (1974) Big Wall Climbing, Oxford University Press « Émile Rey ». pp. 54–55.

Portions of the text are from Cunningham, C.D.; Abney, W. de W. (1888). The Pioneers of the Alps (2nd ed.). Retrieved 22 November 2015. which is in the public domain.