Alexander Gardner (photographer) (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Scottish photographer (1821–1882)

| Alexander Gardner | |

|---|---|

Gardner, c. 1863 Gardner, c. 1863 |

|

| Born | (1821-10-17)October 17, 1821Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland |

| Died | December 10, 1882(1882-12-10) (aged 61)Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Glenwood Cemetery |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom, United States |

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Spouse | Margaret Gardner[1] |

| Children | 2[1] |

Alexander Gardner (October 17, 1821 – December 10, 1882) was a Scottish photographer who immigrated to the United States in 1856, where he began to work full-time in that profession. He is best known for his photographs of the American Civil War, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, and of the conspirators and the execution of the participants in the Lincoln assassination plot.

Alexander was born in Paisley, Renfrewshire, on October 17, 1821. He became an apprentice jeweler at the age of 14, lasting seven years.[2] Gardner was raised in the Church of Scotland and influenced by the work of Robert Owen, Welsh socialist and father of the cooperative movement. By adulthood he desired to create a cooperative community in the United States that would incorporate socialist values. In 1850, Gardner and others purchased land near Monona, Iowa for this purpose, but Gardner never lived there, choosing to return to Scotland to raise more money. He stayed there until 1856, becoming owner and editor of the Glasgow Sentinel in 1851. Visiting The Great Exhibition in 1851 in Hyde Park, London, he saw the photography of American Mathew Brady, and thus began his interest in the field.[3]

In 1856, Gardner and his family immigrated to the United States. Finding that many family members and friends at the cooperative he had helped to form were dead or dying of tuberculosis, he stayed in New York. Gardner initiated contact with Brady and became an assistant to him that year, continuing until 1862. At first, Gardner specialized in making large photographic prints, called Imperial photographs, but as Brady's eyesight began to fail, Gardner assuming increasing responsibilities in Brady's studio. In 1858, Brady put Gardner in charge of his Washington, D.C. gallery.[4]

Civil War photography

[edit]

Alexander Gardner, 1860s

Abraham Lincoln became the President of the United States in the November 1860 election and along with his election came the threat of war. Gardner was well-positioned in Washington, D.C. to document the pre-war events, and his popularity rose as a portrait photographer, capturing the visages of soldiers leaving for war.

Mathew Brady shared his idea with Gardner about photographing the Civil War. Gardner's relationship with Allan Pinkerton, chief of the intelligence operation that would become the Secret Service, was central to promoting Brady's idea to Lincoln. Pinkerton recommended Gardner for the position of chief photographer under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Topographical Engineers. Following that short appointment, Gardner became a staff photographer under General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac. At this point, Gardner's management of Brady's gallery ended. The honorary rank of captain was bestowed upon Gardner, and he photographed the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, developing photos in his travelling darkroom. Gardner's photography was so detailed that relatives could identify their loved ones by their facial features in his images.[5]

Gardner's work has often been misattributed to Brady, and despite his considerable output, historians have tended to give Gardner less than full recognition for his documentation of the Civil War.[6] When Lincoln relieved McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac in November 1862, Gardner's role as chief army photographer diminished. About this time, Gardner ended his working relationship with Brady, probably in part because of Brady's practice of attributing his employees' work as "Photographed by Brady".[6] That winter, Gardner followed General Ambrose Burnside, photographing the Battle of Fredericksburg. Next, he followed General Joseph Hooker. In May 1863, Gardner and his brother James opened their own studio in Washington, D.C., hiring many of Brady's former staff. Gardner photographed the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1863) and the Siege of Petersburg (June 1864–April 1865) during this time.

A carte de visite of a US Navy Lieutenant of US Civil war 1861–1865 Gardner studio

Gardner's Photographic Gallery of the War at 7th and D in Washington, D.C. (Boyd's Washington Directory, 1864 edition, page 15)

Title page of Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War (1866), design by Alfred R. Waud.

In 1866, Gardner published a two-volume work, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War. Each volume contained 50 hand-mounted original prints. The book did not sell well.[7] Not all photographs were Gardner's; he credited the negative producer and the positive print printer. As the employer, Gardner owned the work produced, as with any modern-day studio. The sketchbook contained work by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, James F. Gibson, John Reekie, William Pywell, James Gardner (his brother), John Wood, George N. Barnard, David Knox and David Woodbury, among others. Some of his photographs of Lincoln were considered to be the last taken of the President, four days before his assassination, although later this claim was found to be incorrect; the pictures were actually taken in February 1865, the last one on February 5.[7][8] Gardner would photograph Lincoln on a total of seven occasions while Lincoln was alive.[7] He also documented Lincoln's funeral, and photographed the conspirators involved (with John Wilkes Booth) in Lincoln's assassination. Gardner was the only photographer allowed at their execution by hanging, photographs of which would later be translated into woodcuts for publication in Harper's Weekly.

After the war, Gardner was commissioned to photograph Native Americans who came to Washington to discuss treaties; and he surveyed the proposed route of the Kansas Pacific railroad to the Pacific Ocean. Many of his photos were stereoscopic. After 1871, Gardner gave up photography and helped to found an insurance company. Gardner stayed in Washington until his death. When asked about his work, he said, "It is designed to speak for itself. As mementos of the fearful struggle through which the country has just passed, it is confidently hoped that it will possess an enduring interest."[9] He became sick in the late fall of 1882 and died shortly afterward on December 10, 1882, at his home in Washington, D.C. He was survived by his wife and two children.[1] He was buried in local Glenwood Cemetery.[10]

In 1893, photographer J. Watson Porter, who had worked for Gardner years before, tracked down hundreds of glass negatives made by Gardner, that had been left in an old house in Washington where Gardner had lived. The result was a story in the Washington Post and renewed interest in Gardner's photographs.[11]

A century later[_when?_], photographic analysis suggested that Gardner had manipulated the setting of at least one of his Civil War photos by moving a soldier's corpse and weapon into more dramatic positions.[12][13] In 1961, Frederic Ray of the Civil War Times magazine compared several of Gardner's Gettysburg photos showing "two" dead Confederate snipers and realized that the same body had been photographed in two separate locations. One of his most famous images, Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, has been argued to be a fabrication.[14] This argument, first put forth by William Frassanito in 1975,[15] goes this way: Gardner and his assistants Timothy O'Sullivan and James Gibson had dragged the sniper's body 40 yards (37 m) into the more photogenic surroundings of the Devil's Den to create a better composition. Though Ray's analysis was that the same body was used in two photographs, Frassanito expanded on this analysis in his 1975 book Gettysburg: A Journey in Time, and acknowledged that the manipulation of photographic settings in the early years of photography was not frowned upon.[_citation needed_]

Gardner c. 1860- [

![Dead Confederate artillery horses and dead Confederates[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/The_Civil_War_through_the_camera_-_hundreds_of_vivid_photographs_actually_taken_in_Civil_War_times%2C_together_with_Elson%27s_new_history_%281912%29_%2814760479444%29.jpg/120px-The_Civil_War_through_the_camera_-_hundreds_of_vivid_photographs_actually_taken_in_Civil_War_times%2C_together_with_Elson%27s_new_history_%281912%29_%2814760479444%29.jpg) ](/wiki/File:The%5FCivil%5FWar%5Fthrough%5Fthe%5Fcamera%5F-%5Fhundreds%5Fof%5Fvivid%5Fphotographs%5Factually%5Ftaken%5Fin%5FCivil%5FWar%5Ftimes,%5Ftogether%5Fwith%5FElson%27s%5Fnew%5Fhistory%5F%281912%29%5F%2814760479444%29.jpg "Dead Confederate artillery horses and dead Confederates[16]")

](/wiki/File:The%5FCivil%5FWar%5Fthrough%5Fthe%5Fcamera%5F-%5Fhundreds%5Fof%5Fvivid%5Fphotographs%5Factually%5Ftaken%5Fin%5FCivil%5FWar%5Ftimes,%5Ftogether%5Fwith%5FElson%27s%5Fnew%5Fhistory%5F%281912%29%5F%2814760479444%29.jpg "Dead Confederate artillery horses and dead Confederates[16]")

Dead Confederate artillery horses and dead Confederates[16] - [

![Dead Confederate artillery horses[17]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/AntietamAftermath1862.jpg/120px-AntietamAftermath1862.jpg) ](/wiki/File:AntietamAftermath1862.jpg "Dead Confederate artillery horses[17]")

](/wiki/File:AntietamAftermath1862.jpg "Dead Confederate artillery horses[17]")

Dead Confederate artillery horses[17]

Dead Confederates at the site of a Rebel Artillery Battery; Dunkard Church in background

Confederate dead at Antietam 1862 north of the Dunker Church on the west side of the Hagerstown Pike

Confederate dead near the Hagerstown Pike (Possibly based on the photograph to the immediate right.)- [

![Confederate Dead [18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Antietam%2C_Maryland._Confederate_soldiers_1862.jpg/120px-Antietam%2C_Maryland._Confederate_soldiers_1862.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Antietam,%5FMaryland.%5FConfederate%5Fsoldiers%5F1862.jpg "Confederate Dead [18]")

](/wiki/File:Antietam,%5FMaryland.%5FConfederate%5Fsoldiers%5F1862.jpg "Confederate Dead [18]")

Confederate Dead [18] - [

![A Lonely Grave, Union Soldiers grave.[19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/A_Lonely_Grave%2C_Antietam_1862.jpg/120px-A_Lonely_Grave%2C_Antietam_1862.jpg) ](/wiki/File:A%5FLonely%5FGrave,%5FAntietam%5F1862.jpg "A Lonely Grave, Union Soldiers grave.[19]")

](/wiki/File:A%5FLonely%5FGrave,%5FAntietam%5F1862.jpg "A Lonely Grave, Union Soldiers grave.[19]")

A Lonely Grave, Union Soldiers grave.[19] - [

![Confederate dead at Antietam 1862.[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c5/Confederate_dead_gathered_for_burial_at_Antietam.jpg/120px-Confederate_dead_gathered_for_burial_at_Antietam.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Confederate%5Fdead%5Fgathered%5Ffor%5Fburial%5Fat%5FAntietam.jpg "Confederate dead at Antietam 1862.[20]")

](/wiki/File:Confederate%5Fdead%5Fgathered%5Ffor%5Fburial%5Fat%5FAntietam.jpg "Confederate dead at Antietam 1862.[20]")

Confederate dead at Antietam 1862.[20] - [

!["Confederate soldier who after being wounded had evidently dragged himself to a little ravine on the hillside where he died".[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/Dead_soldier%2C_Antietam.png/120px-Dead_soldier%2C_Antietam.png) ](/wiki/File:Dead%5Fsoldier,%5FAntietam.png ""Confederate soldier who after being wounded had evidently dragged himself to a little ravine on the hillside where he died".[21]")

](/wiki/File:Dead%5Fsoldier,%5FAntietam.png ""Confederate soldier who after being wounded had evidently dragged himself to a little ravine on the hillside where he died".[21]")

"Confederate soldier who after being wounded had evidently dragged himself to a little ravine on the hillside where he died".[21] - [

![Confederate Dead Antietam Maryland 1862 incorrectly identified and sold as taken near "Burnsides Bridge";[22]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/85/Dead_Confederate_soldiers%2C_as_they_fell%2C_on_the_west_bank%2C_near_the_bridge%2C_on_the_left_wing_of_our_Army%2C_at_the_Battle_of_Antietam_LCCN2014646928.jpg/120px-Dead_Confederate_soldiers%2C_as_they_fell%2C_on_the_west_bank%2C_near_the_bridge%2C_on_the_left_wing_of_our_Army%2C_at_the_Battle_of_Antietam_LCCN2014646928.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Dead%5FConfederate%5Fsoldiers,%5Fas%5Fthey%5Ffell,%5Fon%5Fthe%5Fwest%5Fbank,%5Fnear%5Fthe%5Fbridge,%5Fon%5Fthe%5Fleft%5Fwing%5Fof%5Four%5FArmy,%5Fat%5Fthe%5FBattle%5Fof%5FAntietam%5FLCCN2014646928.jpg "Confederate Dead Antietam Maryland 1862 incorrectly identified and sold as taken near "Burnsides Bridge";[22]")

](/wiki/File:Dead%5FConfederate%5Fsoldiers,%5Fas%5Fthey%5Ffell,%5Fon%5Fthe%5Fwest%5Fbank,%5Fnear%5Fthe%5Fbridge,%5Fon%5Fthe%5Fleft%5Fwing%5Fof%5Four%5FArmy,%5Fat%5Fthe%5FBattle%5Fof%5FAntietam%5FLCCN2014646928.jpg "Confederate Dead Antietam Maryland 1862 incorrectly identified and sold as taken near "Burnsides Bridge";[22]")

Confederate Dead Antietam Maryland 1862 incorrectly identified and sold as taken near "Burnsides Bridge";[22] - [

![Dead soldiers at Antietam Maryland 1862 incorrectly identified and sold as dead of the Irish Brigade; another version identifies the deceased as Confederates but at the wrong location;[23][24][25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ae/Group_of_Irish_brigade_as_they_lay_on_the_battlefield_of_Antietam%2C_19th_Sept.%2C_1862.jpg/120px-Group_of_Irish_brigade_as_they_lay_on_the_battlefield_of_Antietam%2C_19th_Sept.%2C_1862.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Group%5Fof%5FIrish%5Fbrigade%5Fas%5Fthey%5Flay%5Fon%5Fthe%5Fbattlefield%5Fof%5FAntietam,%5F19th%5FSept.,%5F1862.jpg "Dead soldiers at Antietam Maryland 1862 incorrectly identified and sold as dead of the Irish Brigade; another version identifies the deceased as Confederates but at the wrong location;[23][24][25]")

](/wiki/File:Group%5Fof%5FIrish%5Fbrigade%5Fas%5Fthey%5Flay%5Fon%5Fthe%5Fbattlefield%5Fof%5FAntietam,%5F19th%5FSept.,%5F1862.jpg "Dead soldiers at Antietam Maryland 1862 incorrectly identified and sold as dead of the Irish Brigade; another version identifies the deceased as Confederates but at the wrong location;[23][24][25]")

Dead soldiers at Antietam Maryland 1862 incorrectly identified and sold as dead of the Irish Brigade; another version identifies the deceased as Confederates but at the wrong location;[23][24][25] - [

](/wiki/File:Dead-soldier-antietam.jpg "Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road.")

](/wiki/File:Dead-soldier-antietam.jpg "Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road.")

Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road. - [

](/wiki/File:BloodyLaneAntietam.jpg "Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road.")

](/wiki/File:BloodyLaneAntietam.jpg "Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road.")

Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road. - [

](/wiki/File:Antietam%5FBattle,%5FBloody%5FLane,%5F1862.jpg "Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road.")

](/wiki/File:Antietam%5FBattle,%5FBloody%5FLane,%5F1862.jpg "Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road.")

Dead Confederates in the "Bloody Lane" road. - [

![View on Battlefield" No 572 [26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/02/View_on_Battle-field.jpg/120px-View_on_Battle-field.jpg) ](/wiki/File:View%5Fon%5FBattle-field.jpg "View on Battlefield" No 572 [26]")

](/wiki/File:View%5Fon%5FBattle-field.jpg "View on Battlefield" No 572 [26]")

View on Battlefield" No 572 [26] - [

!["Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862"[27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Burying_the_Dead_on_the_Battlefield_of_Antietam%2C_September_1862_MET_DP116702.jpg/120px-Burying_the_Dead_on_the_Battlefield_of_Antietam%2C_September_1862_MET_DP116702.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Burying%5Fthe%5FDead%5Fon%5Fthe%5FBattlefield%5Fof%5FAntietam,%5FSeptember%5F1862%5FMET%5FDP116702.jpg ""Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862"[27]")

](/wiki/File:Burying%5Fthe%5FDead%5Fon%5Fthe%5FBattlefield%5Fof%5FAntietam,%5FSeptember%5F1862%5FMET%5FDP116702.jpg ""Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862"[27]")

"Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862"[27] - [

!["Confederate Colonel and horse, both killed at the Battle of Antietam"[28]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Confederate_colonel_and_horse%2C_both_killed_at_the_Battle_of_Antietam_LCCN2012650218.tif/lossy-page1-120px-Confederate_colonel_and_horse%2C_both_killed_at_the_Battle_of_Antietam_LCCN2012650218.tif.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Confederate%5Fcolonel%5Fand%5Fhorse,%5Fboth%5Fkilled%5Fat%5Fthe%5FBattle%5Fof%5FAntietam%5FLCCN2012650218.tif ""Confederate Colonel and horse, both killed at the Battle of Antietam"[28]")

](/wiki/File:Confederate%5Fcolonel%5Fand%5Fhorse,%5Fboth%5Fkilled%5Fat%5Fthe%5FBattle%5Fof%5FAntietam%5FLCCN2012650218.tif ""Confederate Colonel and horse, both killed at the Battle of Antietam"[28]")

"Confederate Colonel and horse, both killed at the Battle of Antietam"[28] - [

!["Dr. A. Hurd, 14th Indiana Volunteers, attending to Confederate wounded after the Battle of Antietam."[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8b/Dr._A._Hurd%2C_14th_Indiana_Volunteers%2C_attending_to_Confederate_wounded_after_the_Battle_of_Antietam_LCCN2014646941.jpg/120px-Dr._A._Hurd%2C_14th_Indiana_Volunteers%2C_attending_to_Confederate_wounded_after_the_Battle_of_Antietam_LCCN2014646941.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Dr.%5FA.%5FHurd,%5F14th%5FIndiana%5FVolunteers,%5Fattending%5Fto%5FConfederate%5Fwounded%5Fafter%5Fthe%5FBattle%5Fof%5FAntietam%5FLCCN2014646941.jpg ""Dr. A. Hurd, 14th Indiana Volunteers, attending to Confederate wounded after the Battle of Antietam."[29]")

](/wiki/File:Dr.%5FA.%5FHurd,%5F14th%5FIndiana%5FVolunteers,%5Fattending%5Fto%5FConfederate%5Fwounded%5Fafter%5Fthe%5FBattle%5Fof%5FAntietam%5FLCCN2014646941.jpg ""Dr. A. Hurd, 14th Indiana Volunteers, attending to Confederate wounded after the Battle of Antietam."[29]")

"Dr. A. Hurd, 14th Indiana Volunteers, attending to Confederate wounded after the Battle of Antietam."[29]

Middle bridge over Antietam Creek, September 1862.

A Sharpshooter's Last sleep

The home of a rebel sharpshooter, Gettysburg (1863)- [

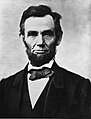

](/wiki/File:Abraham%5FLincoln%5Fhead%5Fon%5Fshoulders%5Fphoto%5Fportrait.jpg "The "Gettysburg Portrait", A head-on photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken on November 8, 1863; eleven days before his Gettysburg Address.")

](/wiki/File:Abraham%5FLincoln%5Fhead%5Fon%5Fshoulders%5Fphoto%5Fportrait.jpg "The "Gettysburg Portrait", A head-on photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken on November 8, 1863; eleven days before his Gettysburg Address.")

The "Gettysburg Portrait", A head-on photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken on November 8, 1863; eleven days before his Gettysburg Address. - [

![Cracked glass portrait of Abraham Lincoln, that was considered to be the last photograph taken of the president before his death. The photo was actually taken in February 1865.[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1d/Gardner-Photo-Lincoln.jpg/77px-Gardner-Photo-Lincoln.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Gardner-Photo-Lincoln.jpg "Cracked glass portrait of Abraham Lincoln, that was considered to be the last photograph taken of the president before his death. The photo was actually taken in February 1865.[8]")

](/wiki/File:Gardner-Photo-Lincoln.jpg "Cracked glass portrait of Abraham Lincoln, that was considered to be the last photograph taken of the president before his death. The photo was actually taken in February 1865.[8]")

Cracked glass portrait of Abraham Lincoln, that was considered to be the last photograph taken of the president before his death. The photo was actually taken in February 1865.[8] - [

![[Bottom] Harper's Weekly drawing showing autopsy of John Wilkes Booth on the USS Montauk (1862). (Based on a lost Alexander Gardner photograph (?))](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cc/Harper%27s_weekly_%281865%29_%2814764461432%29.jpg/80px-Harper%27s_weekly_%281865%29_%2814764461432%29.jpg) ](/wiki/File:Harper%27s%5Fweekly%5F%281865%29%5F%2814764461432%29.jpg "[Bottom] Harper's Weekly drawing showing autopsy of John Wilkes Booth on the USS Montauk (1862). (Based on a lost Alexander Gardner photograph (?))")

](/wiki/File:Harper%27s%5Fweekly%5F%281865%29%5F%2814764461432%29.jpg "[Bottom] Harper's Weekly drawing showing autopsy of John Wilkes Booth on the USS Montauk (1862). (Based on a lost Alexander Gardner photograph (?))")

[Bottom] Harper's Weekly drawing showing autopsy of John Wilkes Booth on the USS Montauk (1862). (Based on a lost Alexander Gardner photograph (?))

David Herold, conspirator to assassination, after arrest, 1865.

George Atzerodt, conspirator to assassination, after arrest, 1865.

Lewis Powell, conspirator to assassination, after arrest, 1865.

Gen. John F. Hartranft and staff, responsible for securing the conspirators at the arsenal

The scaffold

Reading the Warrant

Adjusting the Ropes

The trap is Sprung

After Trap has been Sprung

Conspirator's execution – bodies hanging from scaffold

Graves for the Lincoln Assassination conspirators

View of the scaffold and hanging bodies of the Lincoln Assassination conspirators taken from roof of the arsenal

Portrait of Ta-Tan-Kah-Sa-Pah (Black Bull), 1872- Photographers of the American Civil War

- David Hume Kennerly (influenced by Gardner)[3]

- ^ a b c Joseph M. Wilson (1883). A Eulogy on the Life and Character of Alexander Gardner. p. 20.

- ^ Joseph M. Wilson (1883). A Eulogy on the Life and Character of Alexander Gardner. p. 08.

- ^ a b BBC Scotland (2012). "The Scot who shot the Civil War". BBC.

- ^ "Alexander Gardner [biography]". The Civil War Trust. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ^ "See The First Photo To Capture The Casualties of War". 100 Photographs | The Most Influential Images of All Time. Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Hagen, Charles (July 31, 1992). "A Civil War Image Maker's Belated Recognition". The New York Times. p. C19.

- ^ a b c "Antietam, Maryland. Allan Pinkerton, President Lincoln, and Major General John A. McClernand: Another View". World Digital Library. October 3, 1862. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ a b "Alexander Gardner (1821–1882): Abraham Lincoln, February 5, 1865" (PDF)., Picturing America. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Lee, Anthony W. On Alexander Gardner's photographic sketch book of the Civil War, Berkeley : University of California Press, 2007. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-520-25151-9

- ^ Davis, William C.; Pohanka, Brian C.; and Troiani, Don. Civil War Journal. Nashville, Tenn.: Rutledge Hill Press, 1998, p. 291.

- ^ Michael E. Ruane (December 23, 2011). "Alexander Gardner: The mysteries of the Civil War's photographic giant". Washington Post.

- ^ William A. Frassanito's books: Gettysburg-A Journey in Time page 187+; Early Photography at Gettysburg page 270+

- ^ "A Sharpshooter's Last Sleep". Museum of Hoaxes. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- ^ "The Case of the Moved Body | Does the Camera Ever Lie? | Articles and Essays | Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ Frassanito, William (1975). Gettysburg: A Journey in Time. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 186–192.

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.165-170

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.165-170

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.126-138

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.171-174

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.105-108

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.105-108

- ^ In fact it was taken northeast of the Dunkard church beside the Smoketown road looking west toward the West Woods. Site identified by Robert Kalasky, Military Images Volume XX, Number 6 May–June 1999, pp. 24–29.

- ^ Battlefield near the Sherrick House

- ^ One view is these are dead confederate soldiers taken east of the Dunkard Church southwest of the Mumma Farm. Site identified by Robert Kalasky, "Military Images" Volume XX, Number 6 May–June 1999, pp. 24–29.

- ^ An alternative view is that these are dead soldiers of the 20 New York Infantry see History.Net article at this-antietam-photo-has-been-a-mystery-for-40-years-weve-solved-it-we-think-part-iii

- ^ Not Proven but possibly taken on Sherrick Farm

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.144-147

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.122-125

- ^ Site identified by William Frassanito in Antietam pp.215-223

- "Biographical Sketch" in "Glass Plate Negative of Alexander Gardner Abraham Lincoln Portrait, ca. 1864" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. February 6, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- Gallman, J. Matthew and Gary W. Gallagher, ed. (2015). Lens of War: Exploring Iconic Photographs of the Civil War. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Gardner, Alexander (1959) [1865–1866]. Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War. New York: Dover Publications. online version

- Lowry, Richard S. (2015). The Photographer and the President: Abraham Lincoln, Alexander Gardner, and the Images That Made a Presidency. New York: Rizzoli Ex Libris.

- Katz, Mark D. (1990). Witness to an Era: The Life and Photographs of Alexander Gardner. New York: Viking Studio. ISBN 9780670828203.

- Steiner, Keith (2013). In The Footsteps of Alexander Gardner at Antietam And Gettysburg. Troubador.

- Steiner, Keith (2016). Alexander Gardner: Visionary Photographer of the American Civil War. Troubador.

- Photographic Works of Alexander Gardner, a Public Domain collection of the photographs of Alexander Gardner, at the Internet Archive.

- A Eulogy on the Life and Character of Alexander Gardner, by Joseph M. Wilson at the Internet Archive

- "Alexander Gardner". George Eastman House Collection. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- "Alexander Gardner". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Photojournalism: An Ethical Approach includes a passage on Gardner

- Rays of Sunlight from South America From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Encyclopædia Britannica