American Anti-Imperialist League (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Late 1890s-1920s U.S. group opposed to forced expansion

American Anti-Imperialist League

George S. Boutwell, first President of the Anti-Imperialist League George S. Boutwell, first President of the Anti-Imperialist League |

|

|---|---|

| Formation | June 15, 1898 |

| Founder | Gamaliel Bradford |

| Dissolved | November 27, 1920 |

| Purpose | Opposition to American imperialism |

| Headquarters | Boston |

| Location | United States |

| Presidents | George S. Boutwell (1898-1905) Moorfield Storey (1905-1920) |

The American Anti-Imperialist League was an organization established on June 15, 1898, to battle the American annexation of the Philippines as an insular area. The anti-imperialists opposed forced expansion, believing that imperialism violated the fundamental principle that just republican government must derive from "consent of the governed". The League argued that such activity would necessitate the abandonment of American ideals of self-government and non-intervention—ideals expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence, George Washington's Farewell Address and Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address.[1] The Anti-Imperialist League was ultimately defeated in the battle of public opinion by a new wave of politicians who successfully advocated the virtues of American territorial expansion in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War and in the first years of the 20th century, although the organization lasted until 1920.

Organizational history

[edit]

The idea for an Anti-Imperialist League was born in the spring of 1898. On June 2, retired Massachusetts banker Gamaliel Bradford (banker)[_citation needed_] published a letter in the Boston Evening Transcript in which he sought assistance gaining access to historic Faneuil Hall to hold a public meeting to organize opponents of American colonial expansion.[2] An opponent of the Spanish–American War, Bradford decried what he saw as an "insane and wicked" colonial ambition among some American decision-makers which was "driving the country to moral ruin."[3] Bradford's organizing efforts proved successful, and on June 15, 1898, his protest meeting against "the adoption of an imperial policy by the United States" was held.[4]

The June 15 meeting gave rise to a formal four-member organizing committee known as the Anti-Imperialist Committee of Correspondence, headed by Bradford.[5] This group contacted religious, business, labor, and humanitarian leaders from around the country and attempted to stir them into action to stop what they perceived as a growing menace of American colonial expansion into Hawaii and the former colonial possessions of the Spanish empire.[5] A letter-writing campaign attempting to involve editors of newspapers and magazines was initiated.[5] This initial pioneering effort by Bradford and his associates bore fruit on November 19, 1898, when the Anti-Imperialist Committee of Correspondence formally established itself as the Anti-Imperialist League.[5]

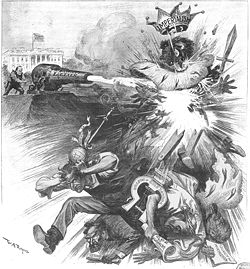

President McKinley fires a cannon into an imperialism effigy in this cartoon by W.A. Rogers in Harper's Weekly of September 22, 1900.

The Anti-Imperialist League was administered by three permanent officers—a President, Secretary, and Treasurer—working in conjunction with a six-member Executive Committee.[6] Unsurprisingly given the localized origins of the organization, the initial members of this leadership group all hailed from the Boston metropolitan area.[6] Chosen as the high-profile President of the League was former Massachusetts Governor, Congressman, and United States Senator George S. Boutwell, who would remain in the position until his death in 1905.[6] Practical day-to-day executive operations were placed in the hands of Secretary Erving Winslow.

In addition to its Boston-based governing center, the Anti-Imperialist League also included a large list of public figures of national reputation who were enlisted as Vice-Presidents of the organization. This post was essentially ceremonial but was important in providing legitimacy to the organization.[6] A total of 18 Vice-Presidents were named at the time of the November formation of the league, including among them former President of the United States Grover Cleveland, ex-US Senator and Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, and labor leader Samuel Gompers.[6]

During the first half of 1899 the number of "paper" Vice-Presidents of the League was boosted to 40, with a number of leading politicians and intellectuals added to the League's letterhead.[7] Included among these were religious philosopher Felix Adler, former Iowa Governor William Larrabee, Republican Congressman Henry U. Johnson, and Stanford University president David Starr Jordan.[7]

Shortly after this expansion, the Executive Committee of the League voted to move the offices of the organization to Washington, D.C., to be better situated for influencing American political leaders.[7] Despite this decision to establish a nexus in the nation's capital, main operations of the organization remained in Boston.[7] The decision to move to Washington was made moot with the establishment of an autonomous Washington Anti-Imperialist League in the fall of 1899.[7] This affiliated group concentrated its efforts on the lobbying of national politicians and removed any need for the Boston-based national organization to shift its headquarters. The Anti-Imperialist League would remain based in Boston for the duration of its existence.[7]

Local organizations

[edit]

The Anti-Imperialist League attempted to establish a network of local organizations in an effort to decentralize and expand the group's propaganda efforts. The group's largest and most influential local affiliates were located in New York City, Philadelphia, Washington, DC, Chicago, Minneapolis, Cincinnati, Portland, Oregon, and Los Angeles.[8]

In February 1899 the national office of the Anti-Imperialist League would peg the group's total membership at "considerably over 25,000."[9] The total number of local branches of the group was reckoned as "at least 100" by November of that year.[8]

Local groups maintained a substantial degree of autonomy and often had unique local monikers, including the American League of Philadelphia and the Anti-Imperialist League of New York.[10] The roster of officers of the New York branch was nearly as expansive and impressive as that of the original Boston organization, including a corps of 23 Vice-Presidents.[11]

Three leagues become one

[edit]

In October 1899 a Chicago group inspired by the Boston organization which had previously styled itself as the Central Anti-Imperialist League held a convention merging with another organization to form the American Anti-Imperialist League.[12] This organization would in turn merge with the Boston-based Anti-Imperialist League in the following month, rechristening the Boston organization as the New England branch of the American Anti-Imperialist League.[8] Despite this formal organizational change, the Boston office remained the leading center of the anti-imperialist movement nationwide.[8]

In 1904, the vital Boston organization was reestablished as the headquarters of the organization.[12] Throughout it all, the loosely affiliated local Leagues would conduct their own activities, electing their own officers and producing their own publications.[10]

One of the primary activities of the Anti-Imperialist League was the production of political leaflets and pamphlets meant to propagandize American imperialist activities.[13] These publications began to emerge immediately in 1898. Included among these were a series of "Broadsides" which made use of extensive quotations from founding fathers of America such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Monroe, attempting to demonstrate a fundamental contradiction between the ideas upon which the American republic was founded and designs for colonial expansion being advanced by the nation's contemporary political leaders.[14]

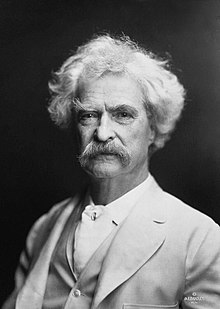

Mark Twain, 1907

Mark Twain, perhaps the most prominent member of the league, offered his voice through the publication of his essay "To the Person Sitting in Darkness," which appeared in the North American Review in February 1901. In his essay, Twain satirically portrayed the moral and cultural superiority of Americans compared to Filipinos to comment on what he believed to be the great irony of the Philippines' annexation. Twain successfully gained popular support for the Anti-Imperialist League by claiming that America's international role was not to subjugate other nations for material gain, but to see "a nation of long harassed and persecuted slaves set free."[15]

The Anti-Imperialist League of New York was particularly prominent in the production of propaganda pamphlets, drawing upon the impressive array of writers, public intellectuals, and politicians among its members.[12]

The war that erupted in 1898 with Spain had its origins in the First Cuban Insurrection (1868–1878). The Cuban rebels had formed relationships with small groups of Americans committed to their cause. Many of these Americans supported the filibusters who attempted to run military supplies to the insurrectionists on the island. War had nearly erupted between the United States and Spain in 1873 when the Spanish captured the filibuster ship Virginius and executed most of the crew, including many American citizens. The Treaty of Zanjón signaled a temporary peace, but American sympathies remained with the Cubans desiring independence. When the reforms promised by the treaty proved illusory, the insurrectionists and their American supporters prepared for a new round.

The 1900 presidential election caused internal squabbles in the League. Particularly controversial was the League's endorsement of William Jennings Bryan, a renowned anti-imperialist but also the leading critic of the gold standard, a position which alienated a substantial segment of the organization's leaders.

A few League members, including Storey and Oswald Garrison Villard, attempted to organize a third party to both uphold the gold standard and oppose imperialism. This effort led to the formation of the National Party, which nominated Senator Donelson Caffery of Louisiana. The party quickly collapsed, however, when Caffery dropped out of the race, leaving Bryan as the only anti-imperialist candidate. Following the death of George Boutwell in 1905, prominent lawyer and civil rights activist Moorfield Storey would serve as President of the organization, filling that role from 1905 until the League dissolved in 1920.

Despite its anti-war record, the League did not object to U.S. entry into World War I (though several individual members did oppose intervention). By 1920, it was only a shadow of its former strength, and it disbanded on November 27, 1920.[16]

- ^ Fred Harvey Harrington, "Literary Aspects of American Anti-Imperialism 1898–1902," New England Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 4 (Dec., 1937), pg. 650.

- ^ E. Berkeley Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States: The Great Debate, 1890–1920. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970; pp. 122–123.

- ^ Gamaliel Bradford, Boston Evening Transcript, June 2, 1898. Quoted in Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 123.

- ^ Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 123.

- ^ a b c d Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 126.

- ^ a b c d e Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 127.

- ^ a b c d e f Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 128.

- ^ a b c d Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 133.

- ^ Report of the Executive Committee of the Anti-Imperialist League, Feb. 10, 1899. Cited in Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 133.

- ^ a b Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 135.

- ^ a b c Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 134.

- ^ Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 131.

- ^ Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States, pg. 132.

- ^ Twain, Mark. "To the Person Sitting in Darkness".

- ^ Ryan, James Gilbert; Schlup, Leonard C. (2003). Historical Dictionary of the Gilded Age. M.E. Sharpe. p. 19. ISBN 9780765621061.

- Address Adopted by the Anti-Imperialist League: February 10, 1898. Boston: Anti-Imperialist League, 1899. —Leaflet.

- Report of the Executive Committee of the Anti-Imperialist League, February 10, 1899. Boston: Anti-Imperialist League, 1899. —Leaflet.

- Erving Winslow, The Anti-Imperialist League: Apologia Pro Vita Sua. Boston: Anti-Imperialist League, n.d. [c. 1909].

- Twain, Mark. "To the Person Sitting in Darkness." Anti-Imperialist League of New York. 1873. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- Nathan G. Alexander, "Unclasping the Eagle's Talons: Mark Twain, American Freethought, and the Responses to Imperialism." The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17, no. 3 (2018): 524–545.

- Thomas A. Bailey, "Was the Presidential Election of 1900 A Mandate on Imperialism?" Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Jun., 1938), pp. 43–52. in JSTOR

- Robert L. Beisner, Twelve Against Empire: The Anti-Imperialists, 1898–1900. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968.

- David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, "Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900," Independent Review, vol. 4 (Spring 2000), pp. 555–575.

- Michael Patrick Cullinane, Liberty and American Anti-Imperialism, 1898–1909. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Fred H. Harrington, "The Anti-Imperialist Movement in the United States, 1898–1900," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Sep., 1935), pp. 211–230. in JSTOR

- Fred Harvey Harrington, "Literary Aspects of American Anti-Imperialism 1898–1902," New England Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 4 (Dec. 1937), pp. 650–667 in JSTOR

- William E. Leuchtenburg, "Progressivism and Imperialism: The Progressive Movement and American Foreign Policy, 1898–1916," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Dec., 1952), pp. 483–504. in JSTOR

- Julius Pratt, Expansionists of 1898: The Acquisition of Hawaii and the Spanish Islands. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1936; pp. 266–278.

- Richard Seymour, American Insurgents: A Brief History of American Anti-Imperialism. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012.

- Richard E. Welch, Jr., Response to Imperialism: The United States and the Philippine-American War, 1899–1902. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1979.

- William George Whittaker, "Samuel Gompers, Anti-Imperialist," Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 38, No. 4 (Nov.1969), pp. 429–445 in JSTOR

- Jim Zwick, Confronting Imperialism: Essays on Mark Twain and the Anti-Imperialist League. West Conshohocken, PA: Infinity Publishing, 2007.

- Jim Zwick, ed. Mark Twain's Weapons of Satire: Anti-Imperialist Writings on the Philippine-American War. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1992.

- Library of Congress webpage with short description

- The League's Platform, from the Internet History Sourcebooks Project at the History Department of Fordham University

- Historical Documents pertaining to the Anti-Imperialist League, at Liberty and Anti-Imperialism (archived 9 October 2007)