Apollo Belvedere (original) (raw)

Hadrianic-era statue

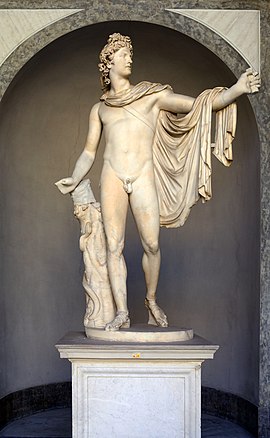

| Apollo Belvedere | |

|---|---|

|

|

Click on the map for a fullscreen view Click on the map for a fullscreen view |

|

| Artist | After Leochares |

| Year | c. AD 120–140 |

| Type | White marble |

| Dimensions | 224 cm (88 in) |

| Location | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

| Coordinates | 41°54′23″N 12°27′16″E / 41.906389°N 12.454444°E / 41.906389; 12.454444 |

The Apollo Belvedere (also called the Belvedere Apollo, Apollo of the Belvedere, or Pythian Apollo)[1] is a celebrated marble sculpture from classical antiquity.

The work has been dated to mid-way through the 2nd century A.D. and is considered to be a Roman copy of an original bronze statue created between 330 and 320 B.C. by the Greek sculptor Leochares.[2] It was rediscovered in central Italy in the late 15th century during the Italian Renaissance and was placed on semi-public display in the Vatican Palace in 1511, where it remains. It is now in the Cortile del Belvedere of the Pio-Clementine Museum of the Vatican Museums complex.

From the mid-18th century it was considered the greatest ancient sculpture by ardent neoclassicists, and for centuries it epitomized the ideals of aesthetic perfection for Europeans and westernized parts of the world.

The Greek god Apollo is depicted as a standing archer having just shot an arrow. Although there is no agreement as to the precise narrative detail being depicted, the conventional view has been that he has just slain the serpent Python, the chthonic serpent guarding Delphi—making the sculpture a Pythian Apollo. Alternatively, it may be the slaying of the giant Tityos, who threatened his mother Leto, or the episode of the Niobids.

The large white marble sculpture is 2.24 m (7.3 feet) high. Its complex contrapposto has been much admired, appearing to position the figure both frontally and in profile. The arrow has just left Apollo's bow and the effort impressed on his musculature still lingers. His hair, lightly curled, flows in ringlets down his neck and rises gracefully to the summit of his head, which is encircled with the strophium, a band symbolic of gods and kings. His quiver is suspended across his right shoulder. He is entirely nude except for his sandals and a robe (chlamys) clasped at his right shoulder, turned up on his left arm, and thrown back.

The lower part of the right arm and the left hand were missing when discovered and were restored by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (1507–1563), a sculptor and pupil of Michelangelo.

Head of Apollo, modeled on the Apollo Belvedere (Marble, Roman copy of c. 120–140 AD), once in the collection of Vincenzo Giustiniani and James-Alexandre de Pourtalès (British Museum)

Detail

Before its installation in the Cortile delle Statue of the Belvedere palace in the Vatican, the _Apollo_—which seems to have been discovered in 1489 in the present Anzio (at that time territory of Nettuno[3]), or perhaps at Grottaferrata where Giuliano della Rovere was abbot in commendam[4]—apparently received very little notice from artists.[5] It was, however, sketched twice during the last decade of the 15th century in the book of drawings by a pupil of Domenico Ghirlandaio, now at the Escorial.[6] Though it has always been known to have belonged to Giuliano della Rovere before he became pope, as Julius II, its placement has been confused until as recently as 1986:[7] Cardinal della Rovere, who held the titulus of San Pietro in Vincoli, stayed away from Rome for the decade during Alexander VI's papacy (1494–1503); in the interim, the Apollo stood in his garden at SS. Apostoli, Deborah Brown has shown, and not at his titular church, as had been assumed.

Once it was installed in the Cortile, however, it immediately became famous in artistic circles and a demand for copies of it arose. The Mantuan sculptor Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi, called "L'Antico", made a careful wax model of it, which he cast in bronze, finely finished and partly gilded, to figure in the Gonzaga collection, and in further copies in a handful of others. Albrecht Dürer reversed the _Apollo'_s pose for his Adam in a 1504 engraving of Adam and Eve, suggesting that he saw it in Rome. When L'Antico and Dürer saw it, the Apollo was probably still in the personal collection of della Rovere, who, once he was pope as Julius II, transferred the prize in 1511 to the small sculpture court of the Belvedere, the palazzetto or summerhouse that was linked to the Vatican Palace by Bramante's large Cortile del Belvedere. It became the Apollo of the Cortile del Belvedere, and the name has remained with it.

In addition to Dürer, several major artists during the late Renaissance sketched the Apollo, including Michelangelo, Bandinelli, and Goltzius. In the 1530s it was engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi, whose printed image transmitted the famous pose throughout Europe.

The Apollo became one of the world's most celebrated art works when in 1755 it was championed by the German art historian and archaeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) as the best example of the perfection of the Greek aesthetic ideal. Its "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur", as he described it, became one of the leading lights of neoclassicism and an icon of the Enlightenment. Goethe, Schiller and Byron all endorsed it.[8] The Apollo was one of the artworks brought to Paris by Napoleon after his 1796 Italian Campaign. From 1798 it formed part of the collection of the Louvre during the First Empire, but after 1815 was returned to the Vatican where it has remained ever since.[9]

The neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova adapted the work's fluency to his marble Perseus (Vatican Museums) in 1801.

The Romantic movement was not so kind to the _Apollo'_s critical reputation. William Hazlitt (1778–1830), one of the great critics of the English language, was not impressed and dismissed it as "positively bad". The eminent art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) wrote of his disappointment with it.

Finally, starting something of a trend among some later commentators, the art critic Walter Pater (1839–1894) adverted to the work's homoerotic appeal by way of explaining why it had been so long lionized.[8] The opinion was not widely accepted. Nevertheless, the work retained much popular appeal and casts of it were abundant in European and American public places (especially schools) throughout the 19th century.[_citation needed_]

The Apollo Belvedere was featured in the official logo of the Apollo 17 Moon landing mission in 1972

The critical reputation of the Apollo continued to decline in the 20th century, to the point of complete neglect. In 1969, a summary of its reception up to that point was provided by the art historian Kenneth Clark (1903–1983):

"...For four hundred years after it was discovered the Apollo was the most admired piece of sculpture in the world. It was Napoleon's greatest boast to have looted it from the Vatican. Now it is completely forgotten except by the guides of coach parties, who have become the only surviving transmitters of traditional culture."[10]

- Dürer, Albrecht, Adam and Eve (1504 engraving)

- Copies of the Apollo Belvedere appear as cultural props in Joshua Reynolds's Commodore Augustus Keppel (1752-3, oil on canvas) and Jane Fleming, later Countess of Harrington (1778–79, oil on canvas).

- Canova, Antonio, Perseus (1801, Vatican Museums, 180x, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- In Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812–18), Byron describes how the statue requites humanity's debt to Prometheus: "And if it be Prometheus stole from Heaven / The fire which we endure, it was repaid / By him to whom the energy was given / Which this poetic marble hath array'd / With an eternal glory—which, if made / By human hands, is not of human thought; / And Time himself hath hallowed it, nor laid / One ringlet in the dust—nor hath it caught / A tinge of years, but breathes the flame with which 'twas wrought." (IV, CLXIII, 161–163; 1459–67).

- Crawford, Thomas, Orpheus and Cerberus (1838–43; Boston Athenaeum, later Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

- Apollo tended by the Nymphs of Thetis

- The head of the Apollo Belvedere is featured prominently in The Song of Love, a 1914 painting by Giorgio de Chirico

- The Sower by Jean-François Millet (1850) is influenced by the Apollo Belvedere in the treatment and pose of the figure in the piece. The pose of the figure is linked to the sculpture as Millet was attempting to heroise the peasant that he was depicting.

- The Minute Man by Daniel Chester French, 1874 at the Old North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts[11]

- In Robert Musil's 1943 novel The Man Without Qualities, the character Ulrich comments "Who still needed the Apollo Belvedere when he had the new forms of a turbodynamo or the rhythmic movements of a steam engine's pistons before his eyes!" [12]

- In her poem "In the Days of Prismatic Color", Marianne Moore writes that "Truth is no Apollo/ Belvedere, no formal thing."[13]

- Arthur Schopenhauer in the third book of The World as Will and Representation (1859) refers to the head of the Apollo Belvedere, admiring it for the way it exhibits human superiority: "The head of the god of the Muses, with eyes far afield, stands so freely on the shoulders that it seems to be wholly delivered from the body, and no longer subjects to its cares."

- Alexander Pushkin refers to Apollo Belvedere in his 1829 poem The Poet and the Crowd ("Поэт и толпа").

- Varden, a character in Dorothy L. Sayers's The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers recounts how he portrayed Apollo in a movie as "a statue that's brought to life ... You couldn't find an atom of offence from beginning to end, it was all so tasteful, though in the first part one didn't have anything to wear except a sort of scarf—taken from the classical statue, you know." One of his audience, a man with a classical education, guesses from the scarf that the actor was speaking of Apollo Belvedere.

- A bust of Apollo Belvedere is a prominent feature of Charles Bird King's 1835 still life The Vanity of the Artist's Dream, which depicts the struggle of classically trained artists to be relevant in the 19th century.

- ^ Réveil, Etienne Achille and Jean Duchesne (1828), Museum of Painting and Sculpture, or Collection of the Principal Pictures, Statues and Bas-Reliefs, in the Public and Private Galleries of Europe, London: Bossanage, Bartes and Lowell, Vol 11, p. 126. ("The Pythian Apollo, called the Belvedere Apollo")

- ^ "Belvedere Apollo". Vatican Museums. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ Paolo Prignani (25 June 2015). "L'Apollo del Belvedere, on CambiaVersoAnzio". cambiaversoanzio.wordpress.com (in Italian). Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (Oxford University Press) 1969:103 first noted the entries in 1489 and a repetition in 1493 in the somewhat chaotic Cesena chronicle of Giuliano Fantaguzzi.

- ^ H. H. Brummer, The Statue Court in the Vatican Belvedere (Stockholm) 1970:44–71, which gives the most concise review of the statue's discovery and its history.

- ^ Weiss 1969:103.

- ^ Deborah Brown, "The Apollo Belvedere and the Garden of Giuliano della Rovere at SS. Apostoli" Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 49 (1986), pp. 235–238.

- ^ a b Barkan, Op. cit., pg 56.

- ^ Gregory Curtis, Disarmed, (New York: Knopf, 2003) pp. 57–61.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth (1969), Civilisation: A Personal View, New York and Evanston: Harper & Row, Publishers, pg 2.

- ^ Roland Wells Robbins, The Story of the Minute Man, (Stoneham, MA: George R. Barnstead & Son, 1945) pp. 13–24.

- ^ Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities vol. 1, (New York: Vintage Books, 1995): 33.

- ^ Marianne Moore, "In the Days of Prismatic Color," The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore (New York: Penguin, 1994): 42.

- Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, 1981. Taste and the Antique (Yale University Press) Cat. no. 8. Critical history of the Apollo Belvedere.

- Entry in the Census of Antique Works of Art and Architecture Known in the Renaissance

- Image of Apollo Belvedere with a fig leaf

- The sculpture shown with and without a fig leaf

- 16th-century engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi

- "Comparing Different Artists – The Apollo Belvedere"

- See also the gold medal of the Apollo Belvedere of the Vatican Museums.

- Apollo Belvedere in the Census database

- L'Apollo del Belvedere: article in the website Cambiaversoanzio (italian)

Media related to Apollo Belvedere at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Apollo Belvedere at Wikimedia Commons