Aqua Virgo (original) (raw)

Ancient Roman aqueduct in Italy

Route of the Aqua Virgo

The Aqua Virgo was one of the eleven Roman aqueducts that supplied the city of ancient Rome. It was completed in 19 BC by Marcus Agrippa, during the reign of the emperor Augustus[1][2][3] and was built mainly to supply the contemporaneous Baths of Agrippa in the Campus Martius.

At its peak, the aqueduct was capable of supplying more than 100,000 cubic metres (100,000,000 L) of water per day.

The name is thought to be derived from the purity and clarity of the water because it does not chalk significantly. According to a legend repeated by Frontinus, thirsty Roman soldiers asked a young girl for water, who directed them to the springs that later supplied the aqueduct; Aqua Virgo was named after her.

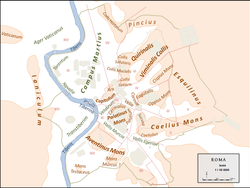

Topological plan of Rome

The only remains above ground, in via del Nazzareno

60 metres (200 ft) stretch of the aqueduct arches, recently found inside the Rinascente shopping complex[4]

Its source is just before the 8th milestone north of the Via Collatina. It collected water from springs near the course of the Aniene, a large system (still functioning and inspectable) of aquifers and springs which were conveyed into a basin (existing until the 19th century) by a series of underground tunnels, and fed the canal by regulating the inflow with a dam. It was also supplemented by several feeder channels along its course.

The aqueduct ran underground for nearly all of its 20.5 kilometres (12.7 mi) length except the last stretch of 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) running partly on arches in the Campus Martius area, of which two sections remain. The aqueduct dropped only 4 metres (13 ft) along its length to its terminus in the centre of the Campus Martius.

The route made a very wide arc, starting from the east and entering the city from the north. It ran along via Collatina up to the Portonaccio area, passed via Nomentana to via Salaria, and then turned south and entered the city under the Horti Lucullani and crossed 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) to the area of the Pincian Hill and current Villa Medici, where a spiral staircase (called the Pincio snail) leads to the underground conduit.

The long detour was justified because the aqueduct had to serve the northern suburb of the city, until then without a water supply, and because the low level source (only 24 metres (79 ft) above sea level) made it necessary to avoid the steep slopes that the shortest route would have encountered. Probably, the entry into the city from that side also allowed the Campus Martius to be reached without crossing densely populated city areas.

After the limaria pool (settling basin) near the Pincian, the urban stretch began partially on arches, many discovered in 1871. It then passed through the area of the Trevi Fountain and then crossed the current Via del Corso on an arch which was subsequently transformed into a triumphal arch to celebrate the military successes of Claudius in Britain. Later interpretation has found that the aqueduct’s arches continued along the Via del Seminario to a point east of the Pantheon.[5]It terminated in the Campus Martius in front of the Saepta Julia.

A secondary branch reached the inadequately served regions VII, IX, and XIV in the Trastevere area. The route passed from the low area of the Campus Martius over the higher ground of the ridge surrounding the Pantheon basin, and then over the bridge of Agrippa. Tiber River.[5]

Distribution was fairly widespread: according to Frontinus, 200 quinaries were reserved for the suburbs, 1457 for public works, 509 for the imperial house, and the remaining 338 for private concessions, all distributed through a network of 18 castella (distribution cisterns) along the route.

There were numerous repairs over time: Tiberius in 37 AD, Claudius between 45 AD and 46 AD, then Constantine the Great[6] and Theodoric.

Emperor Claudius renovated it in 46 AD, as witnessed by an inscription on the architrave in via del Nazzareno, which states that he rebuilt large sections of the aqueduct at this point because Caligula had removed stone for use in constructing an amphitheatre.

In 537 AD, the Goths besieging Rome tried to use this underground channel as a secret route to invade Rome according to Procopius.[7]

After deteriorating and falling into disuse with the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Aqua Virgo was repaired by Pope Adrian I in the 8th century. In 1453, Pope Nicholas V made a complete restoration and extensive remodelling from its source to its terminus points between the Pincio and the Quirinale and within Campo Marzio and consecrated it Acqua Vergine. This also led the water to the Trevi Fountain and the fountains of Piazza del Popolo, which it still serves today.[7] In the 1930s, a pressurised version was built, the Acqua Vergine Nuovo, separate from the other channels.

Most of the ancient aqueducts were gravity systems, that is by ensuring the source was higher than the termination and plotting a uniform course for the aqueduct to follow a downward gradient, gravity would provide all the power needed for the water to flow. The aqueducts were for most of their length channels about 50 centimetres (20 in) to 1 metre (3.3 ft) below ground. Tunnels, pipes, and only the final stretches of the aqueducts used arches. The channels were made of three kinds of material: masonry (the most common form), lead pipes, and terracotta. These channels were made using a “cut and cover” technique where the channel path was cut into the ground and then covered in order to easily access the channels that were in need of repair. The floors and walls of the channels were lined with cement, and the roof was usually a vault. The cement was usually as high as the water would reach, which was meant to be about a half to two thirds full. Lining the walls and floor with cement served three purposes: to protect against leaks and seepage, to provide a smooth contact surface, and to make the contact surface continuous and joint free from one end to the other.[8]

In order to maintain the slight downward gradient, the aqueducts didn’t follow a direct route to Rome, but instead used the lay of the land. Typically, the gradient was shallow to make the water flow slower, so fewer repairs would be needed due to quicker water flows causing damage and too shallow of a gradient meant that the water would not flow at all. Different degrees of gradient were used for different reasons. While traveling through a tunnel, for example, a steeper gradient could be used to speed up water flow. Since inside the tunnel repairs were less likely to be needed the water could flow at a higher rate requiring a steeper gradient and then once through the tunnel the gradient would need to decrease in order for the water to be slowed back down to its average speed. In later times, the use of high arches across valleys and plains were employed for the aqueducts, and some were even as high as 27 metres (89 ft) off the ground.[8]

Besides standard water levels similar to those used by contractors today, other kinds of levels were in use during ancient Roman times.

Chorobates, the ancient Roman device for measuring slopes

- The chorobates, a bench with weighted strings on its sides for measuring the angle of the ground. It had a system of notches and a short channel in the middle, which could have been used for determining the direction of water flow.[9]

- The dioptra was another kind of level which rested on the ground and was adjusted on the top with precision screws for checking the angle of various objects by looking through pivoting sights.[9]

Vitruvius explains that while the chorobates may seem to be superior to the dioptra in a project such as the aqueducts, the chorobates are not immune to wind disturbing the plummets on the device (weighted strings). The dioptra and water levels were immune to this.[9]

- The groma is another surveying tool in use during the ancient Roman times. Although none survive intact today, partial pieces of them are believed to be found in the tomb of Lucius Aebutius Faustus and in a surveyor’s workshop in the remains of Pompeii. A possible reconstruction of this device from these remains is that it might have been a shaft with iron-sheeted enclosed wooden arms in the shape of a cross at the top, and bronze angle-brackets near the center of the arms to help prevent inaccuracy and wear of the wood with a plumb line hanging near the end of each of the arms. The plumb-bobs at the end of the lines were paired in two, opposite of each other from the arms. One would sight down the plummet to its opposite side to get a reading when the cross was off center. The cross was placed on a bracket and not directly on the shaft. The bottom of the bracket fitted into a bronze collar set into the top of the staff. The distance horizontally across from the center of the cross was 23.5 centimetres (9.3 in) while the staff may have been as long as 2 metres (6.6 ft). To use the groma sights could be set onto a second groma a distance away from the first, then two more gromas were positioned the same distance as the first to the second away from the first two at right angles to form a square. The groma enabled the survey of straight lines, squares, rectangles and other geometric shapes.[9]

- A portable sundial was also available for use during this time, as was evident from remains found in Pompeii. It could also sight buildings from each other.[9]

- The libella was another leveling instrument in use during this time and consisted of an A-shaped frame with a horizontal bar on top. A plumbline from the apex was suspended down to the lower bar, indicating when the instrument was level.[9]

Modern day windlass used for an Anchor

Many lifting tools would have been in use during the Roman times in the construction of temples, tall buildings, bridges, and arches to move large stone blocks and materials from, for example, a quarry, to the job site and then lifted into place.

- The windlass consists of a drum on a horizontal axle anchored against displacement. Tensioning a rope to the drum by using some form of a grip, the drum is rotated. The windlass would have been used in cranes during the Roman times.[9]

- The toothed wheel is the most primitive gear and was used by Egyptians to lift water by one gear turned on a horizontal axis, which would turn another gear on a vertical axis.

- To lift water, the Romans used a tool called a tympanum which consisted of a large wheel with many internal sectional chambers_._[9]

- Another water lifting device was the cochlea, which consisted of spiral turning inside a tube.[9]

- A Ctesibica machina is a pump device which could lift water a large height.[9] As described by Vitruvius:

It is to be made of bronze. The lower part consists of two similar cylinders at a small distance apart, with outlet pipes. These pipes converge like the prongs of a fork, and meet in a vessel placed in the middle. In this vessel, valves are to be accurately fitted above the top openings of the pipes. And the valves by closing the mouths of the pipes retain what has been forced by air into the vessel. Above the vessel, a cover like an inverted funnel is fitted and attached, by a pin well wedged, so that the force of the incoming water may not cause the cover to rise. On the cover of the pip, which is called a trumpet, is jointed to it, and made vertical. The cylinders have, below the lower mouths of the pipes, valves inserted above the openings in their bases. Pistons are now inserted from above rounded on the lathe, and well oiled. Being thus enclosed in the cylinders, they are worked with piston rods and levers. The air and water in the cylinders, since the valves close the lower openings, the pistons drive onwards. By such inflation and the consequent pressure, they force the water through the orifices of the pipes into the vessel. The funnel receives water and forces it out by pneumatic pressure through a pipe. A reservoir is provided, and in this way water is supplied from below for fountains.[9]

The aqueducts at first were financed mainly through wealth collected from war and the patronage of wealthy individuals. Taxes from conquered peoples also served to help finance the building by taxation, because the aqueducts were never meant to pay for themselves, but serve as a benefit to the people of Rome. In Republic times, the private use of aqueduct water was not common; only the overflow water was sold to individuals. In Imperial times, the construction of more aqueducts meant that more water was available to be sold for private use.[8]

Locating the source

[edit]

The source of the water was an empirical science in that when the source was obvious such as a spring, lake, or stream, the engineer had to determine the quality of the water. The engineer had to test the taste, clarity, and flow of the water as well as the physique and complexion of the local people who drank it. Soils and rock types were also used as indicators. Clay was regarded as a poor source, while red tufa was considered pure.[8]

Written sources on ancient Roman aqueducts

[edit]

Sextus Julius Frontinus wrote a study, De aquaeductu, on the state of the aqueducts of Rome. He points out that the welfare of the urban community of Rome depends on the quality of the water supply.[10]

Vitruvius, a Roman architect who worked for Caesar and Augustus, wrote the De architectura (On Architecture).[11] One concept contained in the De architectura is that the quality of an architectural work depends on the social relevance of an artist’s work, not the form or workmanship of the work itself. Another assertion from Vitruvius is that a structure must exhibit the three qualities of firmitas, utilitas, and vinustas (in English, it must be strong and durable, useful, and beautiful and graceful).[10]

The Trevi Fountain

The Acqua Vergine is the Renaissance restoration of the Aqua Virgo aqueduct. In 1453, Pope Nicholas V renovated the main channels of the Aqua Virgo and added numerous secondary conduits under Campo Marzio. The original terminus, called a mostra, which means "showpiece", was the stately, dignified wall fountain designed by Leon Battista Alberti in Piazza dei Crociferi. Due to several additions and modifications to the end-most points of the conduits during the years that followed, during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, the Acqua Vergine culminated in several magnificent mostre: the Trevi Fountain and the fountains of Piazza del Popolo.[12]

Two separate aqueducts emerge from the source for the Acqua Vergine unlike the Aqua Virgo:

- Acqua Vergine Antica, which travels underground through some of the same channels constructed by Agrippa's engineers, proceeds into Rome on the northeast under Via di Pietralata, at a point formerly called Fosso Pietralata, crosses Via Nomentana, flows westward toward and through the park of Villa Ada, passes under the western limits of the Villa Borghese, traverses the gardens of Villa Medici, descends the Pincio to Piazza di Spagna, extends under Renaissance Rome to burst forth into the Roman sky in the spectacular, baroque mostra on the Quirinal Hill, the fountain of Trevi.

- Acqua Vergine Nuova, which travels into Rome from the northeast under Via Tiburtina, flows under the Pincio to Porta Pinciana, where it branches into 2 channels:

- one passes southwest to link up, but not mingle, with Acqua Vergine Antica just behind Piazza di Spagna and descends the Pincio to emit its water through the fine, elegant sprays of its regal mostra, the lions of Piazza del Popolo

- one passes northwest under Galoppatoio, curves through the Borghese Gardens, makes a sharp southerly turn toward Piazzale Flaminio to make its triumphant appearance in the triple-arch mostra cascading on the western slopes of the Pincio overlooking Piazza del Popolo.

Today, as in days of old, the Acqua Vergine is regarded to furnish some of the purest drinking-water in Rome, reputed for its restorative qualities. Many people to this day can be seen filling containers for drinking and cooking in its splendid fountains, including:

The fountains of Piazza Navona

- Trevi Fountain

- The fountains of Piazza del Popolo

- The Cascade on the Pincio

- The Lions of the central fountain

- The Rome Group

- The Pantheon fountain in Piazza della Rotonda

- The Colonna fountain in Piazza Colonna

- The Turtle Fountain in Piazza Mattei

- The fountain of Campo de' Fiori

- The north and south fountains of Piazza Navona

- The Neptune Fountain

- The Moor fountain

- The fountains of Piazza Venezia

- Il Facchino (The Porter) in Via Lata

- Fontana della Barcaccia in Piazza di Spagna

- Il Babuino (The Baboon) in Via del Babuino

- List of aqueducts in the city of Rome

- List of aqueducts in the Roman Empire

- List of Roman aqueducts by date

- Parco degli Acquedotti

- Ancient Roman technology

- Roman engineering

- ^ Ovid, Fast. I.464

- ^ Frontinus, de aquis I.4, 10, 18, 22; II.70, 84

- ^ Pliny. Natural History. p. 36.121.

- ^ "Rome's Newest Department Store Features an Ancient Aqueduct". 14 December 2017.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Robert (April 1979). "The Aqua Virgo, Euripus and Pons Agrippae". American Journal of Archaeology. 83 (2): 193–204. doi:10.2307/504901. JSTOR 504901. S2CID 191385140.

- ^ CIL VI, 31564

- ^ a b Karmon, David (August 2005). "Restoring the Ancient Water Supply System in Renaissance Rome: The Popes, the civic administration, and the Acqua Virgine" (PDF). The Waters of Rome. 3: 1–13.

- ^ a b c d Dembskey, Evan (February 2009). "The Aqueducts of Ancient Rome" (PDF). Masters Thesis: 21–56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dembskey, Evan (February 2009). "The Aqueducts of Ancient Rome" (PDF). Masters Thesis: 21–56.

- ^ a b Dembskey, Evan (February 2009). "The Aqueducts of Ancient Rome" (PDF). Masters Thesis: 21–56.

- ^ This work, probably written between 30-27 BCE but possibly even as late as 23 BCE, owes its survival to the palace scriptorium of Charlemagne.

- ^ Karmon, David (August 2005). "Restoring the Ancient Water Supply System in Renaissance Rome: The Popes, the civic administration, and the Acqua Virgine" (PDF). The Waters of Rome. 3: 1–13.

- Aquae Urbis Romae: the Waters of the City of Rome, Katherine W. Rinne

- Aqua Virgo entry on the Lacus Curtius website

- Information on Roman aqueducts

- 'Pipe blunder robs Trevi's supply' at the BBC

- Water stops flowing for Rome's fountains, Guardian

- James Grout, Aqua Virgo, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- (in Italian) Map of Roman aqueducts

41°54′37″N 12°37′37″E / 41.91028°N 12.62694°E / 41.91028; 12.62694