Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (original) (raw)

1989–2019 autonomous region of the Philippines

"ARMM" redirects here. For the program to aid in the control of Usenet abuse, see ARMM (Usenet). For its successor, see Bangsamoro.

| Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao_Rehiyong Awtonomo ng Muslim Mindanao_ (Filipino)الحكم الذاتي الاقليمي لمسلمي مندناو (Arabic) | |

|---|---|

| Former autonomous region of the Philippines | |

| 1989–2019 | |

Flag Flag  Seal Seal |

|

Location within the Philippines Location within the Philippines |

|

| Capital | Cotabato City (provisional and de facto seat of government)Parang (de jure seat of government, 1995–2001)[1] |

| Population | |

| • 2015[2] | 3,781,387 |

| Government | Autonomous government |

| Regional governor | |

| • 1990–1993 | Zacaria Candao (first) |

| • 2011–2019 | Mujiv Hataman (last) |

| Legislature | Regional Legislative Assembly |

| History | |

| • Creation plebiscite | 17 November 1989 |

| • Inauguration | November 6, 1990 |

| • Turnover of ARMM to BARMM | 26 February 2019 |

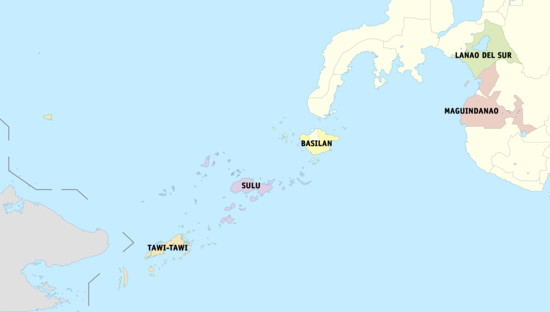

| Political subdivisions | 5 provinces Basilan (except Isabela City) Lanao del Sur Maguindanao Sulu Tawi-Tawi |

Preceded by Succeeded by  Western Mindanao Western Mindanao  Central Mindanao Bangsamoro Central Mindanao Bangsamoro  |

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (Filipino: Rehiyong Awtonomo ng Muslim Mindanao; Arabic: الحكم الذاتي الاقليمي لمسلمي مندناو Al-ḥukm adh-dhātī al-'iqlīmī li-muslimī Mindanāu;[3][4] ARMM) was an autonomous region of the Philippines, located in the Mindanao island group of the Philippines, that consisted of five predominantly Muslim provinces: Basilan (except Isabela City), Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi. It was the only region that had its own government. The region's de facto seat of government was Cotabato City, although this self-governing city was outside its jurisdiction.

The ARMM included the province of Shariff Kabunsuan from its creation in 2006 until July 16, 2008, when Shariff Kabunsuan ceased to exist as a province after the Supreme Court of the Philippines declared the "Muslim Mindanao Autonomy Act 201", which created it, unconstitutional in Sema v. COMELEC and Dilangalen.[5]

On October 7, 2012, President Benigno Aquino III said that the government aimed to have peace in the autonomous region and that it would become known as the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region,[6] a compound of bangsa (nation) and Moro.[7] On July 26, 2018, Aquino's successor, President Rodrigo Duterte, signed the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL), which paved the way for the establishment of a new autonomous political entity in the area, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).[8][9]

ARMM was nominally disestablished after the ratification of BOL and will be effectively replaced by the BARMM upon the constitution of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority, an interim government for the region.[10] The law was "deemed ratified" on January 25, 2019, following the January 21 plebiscite.[11][12][13]

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) was situated in mainland Mindanao in the southern Philippines and was created by virtue of the Republic Act No. 6734 which signed into law by President Corazon Aquino on August 1, 1989. The plebiscite was conducted in the proposed area of ARMM on November 17, 1989, in the provinces of Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi.

The region was strengthened and expanded through the ratification of Republic Act No. 9054, amending for the purpose of Republic Act No. 6734, entitled "An Act Providing for the ARMM" as amended in September 2001. The plebiscite paved the way for the inclusion of the province of Basilan and the city of Marawi as part of ARMM.

For the most part of Philippines' history, the region and most of Mindanao have been a separate territory, which enabled it to develop its own culture and identity. The region has been the traditional homeland of Muslim Filipinos since the 15th century, even before the arrival of the Spanish, who began to colonize most of the Philippines in 1565. Muslim missionaries arrived in Tawi-Tawi in 1380 and started the colonization of the area and the conversion of the native population to Islam. In 1457, the Sultanate of Sulu was founded, and not long after that, the sultanates of Maguindanao and Buayan were also established. At the time when most of the Philippines was under Spanish rule, these sultanates maintained their independence and regularly challenged Spanish domination of the Philippines by conducting raids on Spanish coastal towns in the north and repulsing repeated Spanish incursions in their territory. It was not until the last quarter of the 19th century that the Sultanate of Sulu formally recognized Spanish suzerainty, but these areas remained loosely controlled by the Spanish as their sovereignty was limited to military stations and garrisons and pockets of civilian settlements in Zamboanga and Cotabato,[14] until they had to abandon the region as a consequence of their defeat in the Spanish–American War.

The Moros had a history of resistance against Spanish, American, and Japanese rule for over 400 years. The violent armed struggle against the Japanese, Filipinos, Spanish, and Americans is considered by current Moro Muslim leaders as part of the four centuries long "national liberation movement" of the Bangsamoro (Moro Nation).[15] The 400-year-long resistance against the Japanese, Americans, and Spanish by the Moro Muslims persisted and morphed into their current war for independence against the Philippine state.[16]

In 1942, during the early stages of the Pacific War of the Second World War, troops of the Japanese Imperial Forces invaded and overran Mindanao, and the native Moro Muslims waged an insurgency against the Japanese. Three years later, in 1945, combined United States and Philippine Commonwealth Army troops liberated Mindanao, and with the help of local guerrilla units, ultimately defeated the Japanese forces occupying the region.

In the 1970s, escalating hostilities between government forces and the Moro National Liberation Front prompted President Ferdinand Marcos to issue a proclamation forming an Autonomous Region in the Southern Philippines. This was, however, turned down by a plebiscite. In 1979, Batas Pambansa No. 20 created a Regional Autonomous Government in the Western and Central Mindanao regions.[17]

Establishment of the ARMM

[edit]

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao region was first created on August 1, 1989, through Republic Act No. 6734 (otherwise known as the Organic Act), primarily authored by Aquilino Pimentel Jr.,[18] in pursuance with a constitutional mandate to provide for an autonomous area in Muslim Mindanao.[19] A plebiscite was held in the provinces of Basilan, Cotabato, Davao del Sur, Davao Occidental, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao del Norte, Maguindanao del Sur, Palawan, South Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, Zamboanga del Norte, and Zamboanga del Sur; and in the cities of Cotabato, Dapitan, Dipolog, General Santos, Isabela, Koronadal, Iligan, Marawi, Pagadian, Puerto Princesa, and Zamboanga to determine if their residents wished to be part of the ARMM. Of these areas, only six provinces — Basilan (including Isabela City), Lanao del Sur (including Marawi City), Maguindanao del Norte (including Cotabato City), Maguindanao del Sur, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi — voted in favor of inclusion in the new autonomous region. The ARMM was officially inaugurated on November 6, 1990[20] in Cotabato City, which was designated as its provisional capital. Muslim Mindanao Autonomy Act No. 42, enacted on September 22, 1995, sought to permanently fix the seat of regional government at Parang in Maguindanao del Norte, pending the completion of required buildings and infrastructure.[1] However, the move to Parang was never made. Until the passage of Republic Act No. 9054 in 2001, which directed the ARMM Regional Government to once again fix a new permanent seat of government in an area within its jurisdiction,[21] Cotabato City remained the de facto seat of ARMM's government.

2001 expansion of the ARMM

[edit]

A new law, Republic Act No. 9054, was passed by Congress on February 7, 2001, with a view to expand the territory and powers of the ARMM by amending the original Organic Act (R.A. No. 6734) and calling for a plebiscite to ratify the amendments and confirm which other provinces and cities would like to join the region.[21] RA 9054 lapsed into law on March 31, 2001, without the signature of President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.[21] A plebiscite was held on August 14 in the provinces of Basilan, Cotabato, Davao del Sur, Davao Occidental, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao del Norte, Maguindanao del Sur, Palawan, Sarangani, South Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga del Sur, and Zamboanga Sibugay, and the cities of Cotabato, Dapitan, Dipolog, General Santos, Iligan, Kidapawan, Marawi, Pagadian, Puerto Princesa, Digos, Koronadal, Tacurong, and Zamboanga. In the plebiscite, a majority of votes cast in the original four provinces were in favor of the amendments; outside these areas, only Marawi and the province of Basilan (excluding Isabela City) opted to be included in the ARMM.[21]

Creation and disestablishment of Shariff Kabunsuan

[edit]

The ARMM's sixth province, Shariff Kabunsuan, was carved out of Maguindanao on October 28, 2006.[22] However, on July 16, 2008, the Supreme Court of the Philippines voided the creation of Shariff Kabunsuan, declaring unconstitutional Section 19 in RA 9054 which granted the ARMM Regional Assembly the power to create provinces and cities. The Supreme Court held that only Congress was empowered to create provinces and cities because the creation of such necessarily included the power to create legislative districts, which explicitly under the Philippine Constitution was within the sole prerogative of Congress to establish.[23]

Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain

[edit]

On July 18, 2008, Hermogenes Esperon, peace advisor to then President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, in his talks with Moro Islamic Liberation Front rebels in Malaysia, revealed the planned expansion of the region.[24] The deal, negotiated in secret talks with the MILF and subject to approval, would give the ARMM control of an additional 712 villages on the south west portion of Mindanao, as well as broader political and economic powers.[24]

Massive protests,[_not verified in body_] however, greeted the move of the Philippine government and MILF panels in signing a Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain as a majority of the local government units where these barangays are connected have already opted not to join the ARMM in two instances, 1989 and 2001.

On August 4, 2008, after local officials from Cotabato asked the Supreme Court to block the signing of the agreement between the Philippine government and MILF, the Court issued a temporary restraining order against the signing of the Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) between the Philippine government and the MILF rebels in Malaysia.[25] Several lawmakers had filed petitions with the Supreme Court to stop the Philippine government from concluding the MOA-AD due to lack of transparency and for MILF's failure to cut ties with the al-Qaeda-linked terrorist network Jemaah Islamiyah, which aims to establish a pan-Islamic state in Southeast Asia using MILF camps in southwestern Mindanao as training grounds and staging points for attacks.[26]

On October 14, 2008, the Supreme Court of the Philippines, by a vote of 8–7, declared “contrary to law and the Constitution” the Ancestral Domain Aspect (MOA-AD) of the Tripoli Agreement on Peace of 2001 between the Philippine government and the MILF.[27][28] The 89-page decision, written by Associate Justice Conchita Carpio-Morales ruled: “In sum, the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process committed grave abuse of discretion when he failed to carry out the pertinent consultation process, as mandated by EO No. 3, RA 7160, and RA 8371. The furtive process by which the MOA-AD was designed and crafted runs contrary to and in excess of the legal authority, and amounts to a whimsical, capricious, oppressive, arbitrary and despotic exercise thereof. It illustrates a gross evasion of positive duty and a virtual refusal to perform the duty enjoined.”[29][30][31]

Due to the challenges in establishing the Bangsamoro entity in the previous administrations, then Mayor Rodrigo Duterte of Davao City announced his intent to establish a federal form of government which would replace the unitary form of government in his campaign speeches for the 2016 Philippine presidential election, which he subsequently won. In his plan, ARMM, along with the areas that voted to be included in ARMM in 2001, plus Isabela City and Cotabato City, will become part of a federal state. Aquilino Pimentel Jr., a Duterte ally and advocate for federalism, said in an interview[_when?_] that Isabela City, Basilan, Lamitan, Sulu, and Tawi-tawi may become a single federal state, while Lanao del Sur, Marawi, Cotabato City, and Maguindanao may become a single federal state as well because the Muslims of the Sulu archipelago have a different heritage from the Muslims in mainland Mindanao.

Coastal village in Basilan

Population census of ARMM

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2,108,061 | — |

| 2000 | 2,803,045 | +2.89% |

| 2010 | 3,256,140 | +1.51% |

| 2015 | 3,781,387 | +2.89% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics AuthorityString%5FModule%5FError:%5FString%5Fsubset%5Findex%5Fout%5Fof%5Frange-32" title="null">[32][33] |

Administrative divisions

[edit]

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao consisted of 2 component cities, 116 municipalities, and 2,490 barangays. The cities of Isabela and Cotabato were not under the administrative jurisdiction of the ARMM despite the former being part of Basilan and the latter geographically considered but not politically part of Maguindanao province.

| Province | Capital | Population (2015)String%5FModule%5FError:%5FString%5Fsubset%5Findex%5Fout%5Fof%5Frange-32" title="null">[32] | Area[34] | Density | Cities | Muni. | Barangay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | /km2 | /sq mi | |||||||

| Basilan | Lamitan | 9.2% | 346,579 | 1,103.50 | 426.06 | 310 | 800 | 1 | 11 | 210 |

| Lanao del Sur | Marawi | 27.6% | 1,045,429 | 3,872.89 | 1,495.33 | 270 | 700 | 1 | 39 | 1,159 |

| Maguindanao[a] | Buluan | 31.0% | 1,173,933 | 4,871.60 | 1,880.94 | 240 | 620 | 0 | 36 | 508 |

| Sulu | Jolo | 21.8% | 824,731 | 1,600.40 | 617.92 | 520 | 1,300 | 0 | 19 | 410 |

| Tawi-Tawi | Bongao | 10.3% | 390,715 | 1,087.40 | 419.85 | 360 | 930 | 0 | 11 | 203 |

| Total | 3,781,387 | 12,535.79 | 4,836.23 | 300 | 780 | 2 | 116 | 2,490 | ||

| ^ Figures exclude the independent component city of Cotabato, which is under the jurisdiction of Soccsksargen. |

ARMM organizational structure

[edit]

The Office of the Bangsamoro People, the seat of the ARMM regional government in Cotabato City[35]

The region was headed by a Regional Governor. The Regional Governor and Regional Vice Governor were elected directly like regular local executives. Regional ordinances were created by the Regional Assembly, composed of Assemblymen, also elected by direct vote. Regional elections were usually held one year after general elections (national and local) depending on legislation from Congress. Regional officials had a fixed term of three years, which could be extended by an act of Congress.

The Regional Governor was the chief executive of the regional government, and was assisted by a cabinet not exceeding 10 members. The top official was tasked to appoint the members of the cabinet, subject to confirmation by the Regional Legislative Assembly and also had control of all the regional executive commissions, agencies, boards, bureaus, and offices.

The executive council advises the Regional Governor on matters of governance of the autonomous region. It was composed of the regional governor, 1 regional vice governor, and 3 deputy regional governors (each representing the Christians, the Muslims, and the indigenous cultural communities). The regional governor and regional vice governor had a 3-year term, maximum of 3 terms; deputies' terms are coterminous with the term of the regional governor who appointed them.

| Term | Governor | Party | Vice Governor | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1993 | Zacaria Candao | Lakas-NUCD | Benjamin Loong | Lakas-NUCD |

| 1993–1996 | Lininding Pangandaman | Lakas-NUCD-UMDP | Nabil Tan | Lakas-NUCD-UMDP |

| 1996–2001 | Nurallaj Misuari | Lakas-NUCD-UMDP | Guimid P. Matalam | Lakas-NUCD-UMDP |

| 2001 | Alvarez Isnaji[a] | Lakas-NUCD-UMDP | ||

| 2001–2005 | Parouk S. Hussin | Lakas-NUCD-UMDP | Mahid Miraato Mutilan | Lakas-NUCD-UMDP |

| 2005–2009 | Zaldy Ampatuan | Lakas Kampi CMD | Ansaruddin-Abdulmalik A. Adiong | Lakas Kampi CMD |

| 2009–2011 | Ansaruddin-Abdulmalik A. Adiong[a] | Lakas Kampi CMD | Reggie M. Sahali-Generale[a] | Lakas Kampi CMD |

| 2011–2019 | Mujiv S. Hataman[b] | Liberal | Haroun Al-Rashid Lucman II[b] | Liberal |

| 1 2 3 Acting capacity1 2 Officer-in-charge until June 30, 2013. |

The ARMM had a unicameral Regional Legislative Assembly headed by a Speaker. It was composed of three members for every congressional district. The membership at the time of ARMM's abolition was 24, where 6 are from Lanao del Sur including Marawi City, 6 from Maguindanao, 6 from Sulu, 3 from Basilan, and 3 from Tawi-Tawi.

The Regional Legislative Assembly was the legislative branch of the ARMM government. The regular members (3 members/district) and sectoral representatives, had three-year terms; maximum of three consecutive terms. It exercised legislative power in the autonomous region, except on the following matters: foreign affairs, national defense and security, postal service, coinage and fiscal and monetary policies, administration of justice, quarantine, customs and tariff, citizenship, naturalization, immigration and deportation, general auditing, national elections, maritime, land, and air transportation, communications, patents, trademarks, trade names, and copyrights, foreign trade, and may legislate on matters covered by the Sharia, the law governing Muslims.

ARMM powers and basic principles

[edit]

RA 9054 provided that ARMM "shall remain an integral and inseparable part of the national territory of the Republic." The President exercised general supervision over the Regional Governor. The Regional Government had the power to create its own sources of revenues and to levy taxes, fees, and charges, subject to Constitutional provisions and the provisions of RA 9054. The Sharia applied only to Muslims; its applications are limited by pertinent constitutional provisions (prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment).[17][1][_full citation needed_]

The people of the Bangsamoro region, including Muslims and non-Muslims, have a culture that revolves around kulintang music, a specific type of gong music, found among both Muslim and non-Muslim groups of the Southern Philippines. Each ethnic group in ARMM also has their own distinct architectures, intangible heritage, and craft arts. A fine example of a distinct architectural style in the region is the Royal Sulu architecture which was used to make the Daru Jambangan (Palace of Flowers) in Maimbung, Sulu. The palace was destroyed during the American period due to a typhoon in 1932, and was never rebuilt. It used to be the largest royal palace built in the Philippines. A campaign to faithfully re-establish it in Maimbung town has been ongoing since 1933. A very small replica of the palace was made in a nearby town in the 2010s, but it was noted that the replica does not mean that the campaign to reconstruct the palace in Maimbung has stopped as the replica does not manifest the true essence of a Sulu royal palace. In 2013, Maimbung was officially designated as the royal capital of the Sultanate of Sulu by the remaining members of the Sulu royal family.[36][37][38]

Ginakit boat of the Maguindanaon people

Daru Jambangan (Palace of Flowers) in Maimbung, Sulu before it was destroyed by a typhoon in 1932.

A Moro brass lantaka or swivel gun.

19th century illustration of a lanong, the main warships used by the Iranun and Banguingui people

Tausūg horsemen in Sulu, taken on December 30, 1899.

Yards of Yakan people's cloths

A Sama-Bajau lepa houseboat (c. 1905)

Pis siyabit (headscarf) of the Tausūgs

Palapa, a culturally important spicy condiment of the Maranao people

Tausūg dancers in traditional attire.

A malong bearing okir designs.- [

](/wiki/File:Basih%5Fweapons.jpg "Moro blades made from Basilan "basih" (iron)")

](/wiki/File:Basih%5Fweapons.jpg "Moro blades made from Basilan "basih" (iron)")

Moro blades made from Basilan "basih" (iron)

Pastil, a traditional Maguindanaon food.

Lami-Lamihan Festival

A Maranao kulintang ensemble with okir carvings

| Body |  Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao |

Republic of the Philippines(Central Government only) Republic of the Philippines(Central Government only) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional Document | ARMM Organic Act (Republic Act No. 6734) | Constitution of the Philippines | |

| Head of State / Territory | Regional Governor of the ARMM | President of the Philippines | |

| Head of Government | |||

| Executive | Executive Departments of the ARMM | Executive Departments of the Philippines | |

| Legislative | Unicameral: Regional Legislative Assembly | Bicameral: Senate and Congress | |

| Judiciary | None (under Philippine government) | Supreme Court | |

| Legal Supervisoryor Prosecution | None (under Philippine government) | Department of Justice | |

| Police Force(s) | None (under Philippine government) | Philippine National Police | |

| Military | None (under Philippine government) | Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) | |

| Currency | Philippine peso | Philippine peso | |

| Language(s) | Official: English, FilipinoAuxiliary: Arabic, Tausug, Maranao, Zamboangueño, Yakan, Sama, Badjao, Maguindanaoan, Iranun, Manobo, Bagobo, Tiruray, T'boli | Official: Filipino, EnglishAuxiliary: Spanish, Arabic | |

| Foreign relations | None (under Philippine government) | full rights | |

| Shariah law application | Yes, for Muslims only[39] | Yes, for Muslims only[39] |

- Moro people

- Bangsamoro

- Peace process with the Bangsamoro in the Philippines

- Islam in the Philippines

- Consortium of Bangsamoro Civil Society

- Federalism in the Philippines

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- ^ a b Regional Legislative Assembly of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (September 22, 1995). "An Act Fixing the Permanent Seat of Government for the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao at the Municipality of Parang, Province of Maguindanao" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ Census of Population (2015). Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ "Official Issuances". Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ Narvaez, Eilene Antoinette G.; Macaranas, Edgardo M., eds. (2013). Mga Pangalan ng Tanggapan ng Pamahalaan sa Filipino – Edisyong 2013 (PDF) (in Filipino and English). Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino. p. 38. ISBN 978-971-0197-22-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 29, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ Llanto, Jesus F. (July 17, 2008). "Supreme Court voids creation of Shariff Kabunsuan". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ Pedrasa, Ira (October 7, 2012). "Govt reaches deal with MILF to end rebellion". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Oliveros, Renato T. (February 8, 2013). "The Bangsamoro reframes the Muslim-Filipino identity". The Guidon. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ "Duterte signs Bangsamoro law". ABS-CBN News. July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ "Duterte signs Bangsamoro Organic Law". CNN Philippines. July 26, 2018. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ Arguillas, Carolyn (February 2, 2019). "Appointments to Bangsamoro transition body out after Feb. 6 plebiscite". MindaNews. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "Comelec ratifies Bangsamoro Organic Law". BusinessMirror. January 26, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Depasupil, William; Reyes, Dempsey (January 23, 2019). "'Yes' vote prevails in 4 of 5 provinces". The Manila Times. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Galvez, Daphne (January 22, 2019). "Zubiri: Overwhelming 'yes' vote for BOL shows Mindanao shedding its history of conflict". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Mindanao Peace Process, Fr. Eliseo R. Mercado, Jr., OMI.

- ^ Banlaoi 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Banlaoi 2005 Archived February 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p. 68.

- ^ a b "ARMM history and organization". GMA News Online. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Non-voting campaigner". Manila Standard. Kagitingan Publications, Inc. September 26, 1989. p. 10. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ "Republic Act No. 6734". Official Gazette. Republic of the Philippines. August 1, 1989.

- ^ "Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao". United Nations. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Congress of the Philippines (March 31, 2001). "Republic Act No. 9054 – An Act to Strengthen and Expand the Organic Act for the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, Amending for the Purpose Republic Act No. 6734, entitled "An Act Providing for the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao," as Amended" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 17, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ "Did you know that… ARMM now has Six Provinces". Philippine Statistics Authority. March 26, 2007. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ Llanto, Jesus F. (July 16, 2008). "Supreme Court voids creation of Shariff Kabunsuan". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ^ a b "Philippines Muslim area to expand". BBC News. July 17, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Chavez, Lei (August 15, 2008). "Timeline: GRP-MILF peace process". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ SENATORS: GOVT FAILED TO CUT TIES OF MILF W/ TERROR NETWORK JI Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (August 26, 2008)

- ^ Agreement on peace between the government of the Republic of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, June 22, 2001.

- ^ MoA with MILF unconstitutional – SC, Manila Bulletin, October 15, 2008.

- ^ SC Declares MOA-AD Unconstitutional, Manila Bulletin, October 15, 2008.

- ^ Rufo, Aries (October 14, 2008). "Palace loses ancestral domain case with 8-7 SC vote". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Torres, Tetch (October 14, 2008). "SC: MILF deal unconstitutional". Inquirer.net. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ String%5FModule%5FError:%5FString%5Fsubset%5Findex%5Fout%5Fof%5Frange%5F32-0" title="null">a String%5FModule%5FError:%5FString%5Fsubset%5Findex%5Fout%5Fof%5Frange%5F32-1" title="null">b Census of Population (2015). Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ "Population and Annual Growth Rates for The Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities" (PDF). 2010 Census and Housing Population. Philippine Statistics Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "Bangsamoro Development Plan Integrative Report, Chapter 10" (PDF). Bangsamoro Development Agency. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016. See also talk page.

- ^ "Office of the Bangsamoro People inaugurated". The Manila Times. August 1, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Ramos, Marlon (October 20, 2013). "Before his death, Kiram III tells family to continue fight to re-possess Sabah". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ "Sulu Sultan dies from kidney failure". The Manila Times. September 20, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Whaley, Floyd (September 21, 2015). "Esmail Kiram II, Self-Proclaimed Sultan of Sulu, Dies at 75". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Marcos, Ferdinand E. (February 4, 1977). "Presidential Decree No. 1083 – A DECREE TO ORDAIN AND PROMULGATE A CODE RECOGNIZING THE SYSTEM OF FILIPINO MUSLIM LAWS, CODIFYING MUSLIM PERSONAL LAWS, AND PROVIDING FOR ITS ADMINISTRATION AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES". The LawPhil Project. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

![]()