Black-backed puffback (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Species of bird

| Black-backed puffback | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| male and female, D. c. okavangensis | |

| Conservation status | |

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[1] Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[1] |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Malaconotidae |

| Genus: | Dryoscopus |

| Species: | D. cubla |

| Binomial name | |

| Dryoscopus cubla(Latham, 1801) |

The black-backed puffback (Dryoscopus cubla) is a species of passerine bird in the family Malaconotidae. They are common to fairly common sedentary bushshrikes in various wooded habitats in Africa south of the equator. They restlessly move about singly, in pairs or family groups, and generally frequent tree canopies. Like others of its genus, the males puff out the loose rump and lower back feathers in display, to assume a remarkable ball-like appearance.[2] They draw attention to themselves by their varied repertoire of whistling, clicking and rasping sounds. Their specific name cubla, originated with Francois Levaillant, who derived it from a native southern African name, where the "c" is an onomatopoeic click sound.[3] None of the other five puffback species occur in southern Africa.

They measure about 17 cm in length,[4] and the sexes are similar though easily distinguishable. Adult males have the upperparts deep blue-black with a slight luster.[5] The black cap subtends the red eye, the upperpart plumage is black-and-white, and the underparts pure white.[6] Females have a black loral stripe and white supraloral feathering, with the ear coverts pale and the crown not solidly black. They also have greyer backs than males, and grey to buffy tones to the white plumage tracts. Immature birds resemble females, but have brownish bills and brown irides,[7] while the upperparts and flanks are still greyer, and the underparts and edges of the wing feathers are yet more buffy.[8][6] Intraspecific variation is clinal. Range, iris colour, wing markings and the female plumage assist in separating it from other puffback species.

They occur mainly south of the equator in sub-Saharan Africa, from southern Somalia to coastal South Africa. From the vicinity of the equator and northwards it is replaced by the somewhat larger northern puffback, with which it forms a superspecies.[7]

They are commonly found in gardens, riparian thickets, mangroves, woodlands, moist (or less commonly arid) savanna, bushveld and especially towards the south, fringes of afromontane forest.[5] They are present from sea level to some 2,200 m.a.s.l.,[8][6] and are the only puffback species to occur over much of their range.[7] Highest reporting rates are from the densest woodlands, though all woodland types, including Racosperma plantations, are utilized. In southern Africa the highest reporting rates are from miombo (including the Eastern Highlands), gusu, mopane, various mixed woodlands, whether moist or arid, and riparian fringing forest, including that of the Okavango Delta.[9][10]

A density of 1 pair per 42 ha was recorded in broadleaved Terminalia-Burkea woodland at Nylsvley, South Africa, and a breeding territory is thought to encompass some 4 ha.[4][9] Intensive farming and human pressure have destroyed large tracts of their natural habitat in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces of South Africa.[9][5] They are naturally absent from arid Acacia scrub, Acacia savanna on the Zimbabwean plateau, and the treeless highveld and alpine regions of southern Africa. It also avoids the Congo Basin and, for the most part, tree canopies at the interior of afromontane forests.[10]

Interaction between two individuals in a suburban setting

They usually occur in pairs and actively move about the higher strata of trees, sometimes in mixed-species flocks.[8] Displaying males fly about and call loudly while puffing out the long and loose white feathers of the lower back. In his display flight the male may utter a chow-chow-chow-... call, besides a tik-weeu, tik-weeu, ...[8] (also rendered: dzlit-toweeeyoo, or tzr-t'weeeyo).[4] The male may also utter a click followed by an upslurred whiplash, to which the female may reply with a ssssshh ssssshh.[8] Their food consists of large numbers of caterpillars, besides beetles, ants, termites and small fruit.[4] It is considered sedentary where it occurs, as retraps do not exceed a 10 km radius.[4][5]

Species interactions

[edit]

They are preyed on by the African goshawk, and their nest contents fall prey to the grey-headed bushshrike. They may be killed by ants[5] or come under attack by territorial boubou shrikes. They are parasitised by the black cuckoo and emerald cuckoo, besides perhaps klaas's cuckoo and the red-chested cuckoo.[5]

It is monogamous[11] and single-brooded like other studied species of Dryoscopus.[5] The nest is completed by the female in about 11 days, at which time she is accompanied by the male which regularly calls and displays. The nest is a neat, sharp-rimmed cup, which is constructed of strips of bark which are tied together, and to the supporting branches, with ample amounts of cobweb. It is usually placed in an upright fork in the canopy of a tree with matching smooth, grey bark.[11] The female incubates for 13 to 14 days after she completed laying the clutch of two to three eggs at day intervals.[11] The eggs are distinctly speckled, sometimes forming a ring around the blunter end. Both parents rear the chicks, which leave the nest after some 18 days.[11]

Breeding takes place during the summer months in southern Africa,[9] but less predictably in the tropics.[4] In southern Africa, breeding generally occurs earlier in the moist east (October–December) than in the dryer west. In Zimbabwe it occurs mainly in spring (September–November), but with records in most months,[10] while the breeding peak in Transvaal is 1–2 months later (September–January).[9]

Male and female D. c. affinis, illustrated by Otto Finsch. This coastal race intergrades with D. c. hamatus in their contact zone.[6]

There are five accepted races.[4] Races affinis and cubla seem to represent phenotypic extremes, while the remaining three represent intermediates. Distinction relies on physical proportions, whiteness of male plumage, female upperpart colours and presence of a loral spot, and the extent of white wing markings in either sex.[5] D. c. chapini is subsumed in D. c. hamatus.

- D. c. affinis (G.R.Gray, 1837) – coastal Somalia to coastal Tanzania, including offshore islands

Description: Both sexes lack white edging to remiges and wing coverts.[7] White scapular bar distinct in male, but indistinctly grey in female. Female has black loral spot.[5]

- D. c. nairobiensis Rand, 1958 – plateau east of Rift Valley

Description: Marginally smaller than nominate, and similar to hamatus, but female has black loral spot.[4]

- D. c. hamatus Hartlaub, 1863 – tropical lowlands to southern lowveld

Description: Pure white lower back, rump and underpart plumage in male, greyer in female. Broader white edging to remiges than nominate, and prominent white scapular bar. Irides red.[3]

- D. c. okavangensis Roberts, 1932 – inland southern Africa

Description: Off-white underpart plumage. Central lower back and rump washed grey. Broader white edging to remiges than nominate. Female has prominent supercillium. Irides red.[3]

- D. c. cubla (Latham, 1801) – afromontane and coastal regions of South Africa

Description: Distinctly greyish lower back, rump and underpart plumage, contrasting with white belly. Narrow white edging to remiges and wing coverts, and limited white scapular bar. Irides orange.[3]

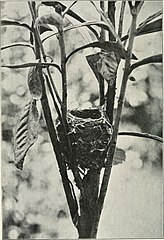

Nest wedged in the branches of a sapling

Head of male, showing red iris

Displaying male with back feathers raised

Male bird showing white back plumage

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Dryoscopus cubla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22707463A94125722. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22707463A94125722.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Daniels, Dick. "Bushshrikes: Genus Dryoscopus". BIRDS of THE WORLD - An Online Bird Book. carolinabirds.org. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d Chittenden, H.; et al. (2012). Roberts geographic variation of southern African birds. Cape Town: JVBBF. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-1-920602-00-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fry, H. (2017). "Black-backed Puffback (Dryoscopus cubla)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harris, Tony; Franklin, Kim (2000). Shrikes & bush-shrikes: including wood-shrikes, helmet-shrikes, flycatcher-shrikes, philentomas, batises and wattle-eyes. London: C. Helm. pp. 35, 104–105, 264–266. ISBN 9780713638615.

- ^ a b c d Zimmerman, Dale A.; et al. (1999). Birds of Kenya and Northern Tanzania. Princeton University Press. p. 495. ISBN 0691010226.

- ^ a b c d Sinclair, Ian; Ryan, Peter (2010). Birds of Africa south of the Sahara (2nd ed.). Cape Town: Struik Nature. pp. 580–581. ISBN 9781770076235.

- ^ a b c d e Terry Stevenson; John Fanshawe (2004). Birds of East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi. Helm Field Guides. pp. 472–473. ISBN 0713673478.

- ^ a b c d e Harrison, J. A., ed. (1997). The Atlas of Southern African birds: Vol.2 Passerines (PDF). Johannesburg: BirdLife South Africa. pp. 428–429. ISBN 0-620-20730-2. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Irwin, M. P. S. (1981). The Birds of Zimbabwe. Salisbury: Quest Publishing. pp. 221–222. ISBN 086-9251-554.

- ^ a b c d Tarboton, Warwick (2001). A Guide to the Nests and Eggs of Southern African Birds. Cape Town: Struik. p. 141. ISBN 1-86872-616-9.