Borgo Vecchio (Rome) (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Former road in Rome

Borgo Vecchio

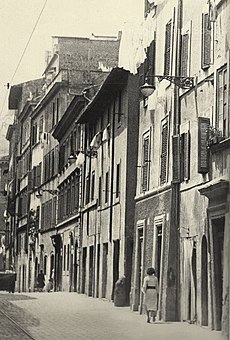

Partial view of the north side of the road: the building in background on the far left is the Palazzo dei Convertendi Partial view of the north side of the road: the building in background on the far left is the Palazzo dei Convertendi |

|

|---|---|

| Former name(s) | Via SanctaCarriera SanctaCarriera Martyrum |

| Width | 6.90 m |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

| Quarter | Borgo |

| East end | Piazza Pia |

| West end | Piazza Rusticucci |

| Construction | |

| Demolished | 1936–1940 |

Borgo Vecchio, also named in the Middle Ages Via Sancta, Carriera Sancta (both "Holy road") or Carriera Martyrum ("Martyrs road"), was a road in the city of Rome, Italy, important for historical and architectural reasons. The road was destroyed together with the adjacent quartier in 1936–37 due to the construction of Via della Conciliazione.

Borgo in 1779 (Map printed by Monaldini). Borgo Vecchio is the second road from the south among the seven that radiate from the Castle.

Located in the Borgo rione, the road stretched roughly in the east–west direction, between Piazza Pia, which marked the entrance of the Borgo near the right bank of the Tiber, and Piazza Rusticucci, which until its demolition was the vestibule of Saint Peter's Square.[1]At about two thirds of its length, Borgo Vecchio crossed Piazza Scossacavalli, the center of the rione.[2]Together with the nearby road of Borgo Nuovo, completed in 1499, Borgo Vecchio delimited the so-called spina (the name derives from its resemblance with the median strip of a Roman circus), composed of several blocks elongated in an east west direction between Castel Sant'Angelo and St. Peter's Basilica.[3][1]

During the Middle Ages the road was called Via Sancta[4] or also, with a term of French origin, Carriera Sancta[5] and Carriera Martyrum, because of the martyrs who went to die in Circus of Nero.[5][6] The name Borgo Vecchio dates back to after 1570, by analogy with the nearby Borgo Nuovo.[7] In fact from that period was so renamed the Via Alessandrina in Borgo; this was due to the opening of another Via Alessandrina in the city:[7] the new road, lying in rione Monti, was so named after its promoter, cardinal Michele Bonelli, nicknamed "Cardinale Alessandrino" from his city of origin in Piedmont. [7]

Roman age and Middle Ages

[edit]

During the Roman Age a road, the via Cornelia, run through the Ager Vaticanus region in east–west direction. It is disputed among the scholars whether this road followed the same path as the future Borgo Vecchio road,[8] or ran north of it, just in the middle of the spina.[9]

Since the early Middle Ages many sources – starting in the 6th century with Procopius[10] and ending in the 13th century with the author of the Life of Cola di Rienzo[11] – mention a covered passage, the portica, erected to protect from sun and rain the pilgrims going to St. Peter and coming from the city through Ponte Sant'Angelo. These, after entering a gate (later named Porta Castello) could walk through the Borgo of the Saxons (today's Borgo S. Spirito) or run under the Portica or Porticus (named also Porticus Sancti Petri). It is probable that the portico was a path of Roman origin, the Porticus Maior, which had two arches at its ends.[5] According to several scholars, the portico would have been located roughly in the center of today's Via della Conciliazione; according to others, however, it would have had the same layout as the future Borgo Vecchio.[5] An indication in favor of the last hypothesis is Borgo Vecchio's width, which was almost everywhere constant with a value of 6.90 metres (22.6 ft).[12] However, despite the many accounts, during the demolition works for the construction of Via della Conciliazione nothing was found hinting to the existence of a covered passage.[8] It is then possible that as Portica was meant the succession of house porches, a common feature in Roman medieval architecture, which allowed the pilgrims to reach Saint Peter from Ponte Sant'Angelo without walking on open air.[8]

The popes always took great care of this path; Adrian I (r. 772–95) had more than 12,000 blocks of tufa extracted from the Tiber, widening and repairing the road; Paschal I (r. 817–24) and Leo IV (r. 847–55) carried out restorations after the two terrible fires that devastated Borgo; Innocent II (r. 1130–43) renewed the tile roofing of the road.[13]

During the Avignon Papacy the flow of pilgrims to Rome fainted causing Rome and the Borgo to decay. Assuming that the Portica existed, it should have collapsed during this period, and was never restored, since the popes understood well that any covered passage could have been a precious shelter for enemies trying to assault the castle and to reach the bridge.[13] In its place appears in the sources the street called Via Sancta[4] or also, with a term of French origin, Carriera Sancta[5] and Carriera Martyrum.[5][6]

Until the begin of the Renaissance Borgo Vecchio and Borgo Santo Spirito were the only roads which allowed pilgrims coming from the left bank to reach Saint Peter.[5]

Rome at the end of the 15th century according to Schedel: Borgo Vecchio is the road between the Castle and Saint Peter left of the pyramid called Meta Romuli

Palazzo Cesi in its original form with 12 windows and the angular tower facing Borgo Vecchio, around 1900

In the late 15th century, after the beginning of the Renaissance, two other roads leading to Saint Peter from Ponte Sant'Angelo were built: Borgo Sant'Angelo, also known as Via Sistina after Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1471–84), running just south of the Passetto (the covered passage linking Vatican with the Castle),[14] and Borgo Nuovo, also known as Via Alessandrina, after Pope Alexander VI Borgia (r. 1492–1503), who erected it.[15] The construction of these two roads solved the traffic problems between the city and Saint Peter, causing in turn the neglection of Borgo Vecchio, which was relegated to the role of a local road.[16]The street, however, was bricked up in 1474 by Sixtus IV.[17]

Due to its diminished importance, the road was less touched than the nearby Borgo Nuovo by the building flurry during the high Renaissance: however, some new buildings were erected in that period also there.[18]

In front of the church of Santa Maria in Traspontina, Antonio da Sangallo the younger erected between Borgo Vecchio and Borgo Nuovo the Palazzo delle Prigioni di Borgo, originally designed as home of Protonotary apostolic Giovanni dal Pozzo, and later converted into jail.[19] The palace was demolished in 1937, but its portal was reused in a new building erected by Marcello Piacentini at Via della Conciliazione n 15.[20]

Another important building was a palazzetto at n. 121–22 erected by Pope Gregory XIII (r. 1572–85) as a residence for the staff of the Hospital of Santo Spirito in Sassia; it had a rusticated ground floor, windows on the piano nobile with alternate triangular and curved tympanums and an arched attic.[21] It was restored and doubled in 1789 by Giuseppe Valadier on the initiative of Monsignor Francesco Albizzi, precettore of the hospital.[21] The building until its demolition showed above the two doors the coats of arms of Albizzi and the Pope.[18] Its lines (but not the coats of arms) were reproduced in the 4–storey building located at Via della Conciliazione n. 7 at the corner with Via dell'Ospedale.[21]

Not far from piazza Scossacavalli, on the right side of the road, lay the oratory of San Sebastiano a Scossacavalli,[18] a dependency of the nearby church of San Giacomo, whose construction began in 1600 and whose façade remained unfinished.[22]

Behind San Sebastiano the road led to Piazza Scossacavalli, whose southern side hosted the palazzo erected by Baccio Pontelli on behalf of Cardinal Domenico della Rovere, nephew of Sixtus IV, now part of the south side of Via della Conciliazione.[22] The house between Borgo Vecchio and the southwest corner of the piazza hosted in the 15th century two deposed queens: Catherine of Bosnia, which lived there in 1477–78,[23] and Charlotte of Cyprus.[24]

Proceeding further towards Saint Peter, it lay the house of Gaspare Torello, archiater of Pope Alexander VI.[25] At this point, on the south side of the road, in 1565 was built the Palazzo Serristori.[26]

Further west, on the north side, the Cybo, a noble family which reached the papal seat with Pope Innocent VIII (r. 1484–92), erected their houses at the end of the 15th century. In front of them Francesco Armellini Medici, cardinal of San Callisto, let build its palace,[27] which was later bought by the Cesi family. This palace, rebuilt in 1575 by Martino Longhi the Elder, [26] still exists, although mutilated, along Via della Conciliazione.[28]

The last buildings on the south side of the road before its end on piazza Rusticucci were the church of San Lorenzo in Piscibus ("St. Lawrence in the fish market", still existing, although stripped of its baroque superstructures and decorations and hidden in the yard of the southern propylaea of Saint Peter's Square)[29][30] and the Palazzo Alicorni, a severe Renaissance palace demolished in 1931 to delimit the border of Vatican City after the signing of the Lateran treaties.[27] Named at the beginning of 19th century Palazzo della Gran Guardia (or della Guardia Reale) after the Guard which mounted daily to protect the pope when he was in the Vatican Palace, the edifice has been rebuilt along Borgo Santo Spirito 10 years after his demolition.[27]

Baroque and Modern Age

[edit]

Piazza Scossacavalli and the Borgo Vecchio towards east during the Tiber flood of 15 February 1915

Around 1660, during the reign of Pope Alexander VII (r. 1655–67), after the construction of the colonnade of Bernini, the first block of the spina between Borgo Vecchio and Borgo Nuovo towards St. Peter, named isola del Priorato after the building hosting the Priory of the Knights of Rhodes,[31] was pulled down in order to create a space–the Piazza Rusticucci–which allowed the full view of Saint Peter's dome, hidden by the nave of Maderno.[32] In this way Borgo Vecchio was deprived of its western end.

At the beginning of the 19th century, when Rome was part of the First French Empire, the prefect of the city, de Tournon, started the demolition of the spina. Anyway, at the fall of Napoleon only the first house at the east end of the road had been demolished,[32] and after the return of the Pope the previous situation was restored.

At the east end of the spina between Borgo Vecchio and Borgo Nuovo, in 1850 a new building, palazzo Sauve, was erected;[33] this replaced a house which had been pulled down during the Roman Republic of 1849. [33]On the east façade of the building a large fountain, the Fontana dei Delfini ("Dolphins' Fountain") was erected by Pope Pius IX (r. 1846–78) in 1861, marking the beginning of the "spina".[34] The palace was demolished in 1936 and the fountain was moved to the Vatican City in 1958.[34][33]

In 1858 at the beginning of the Borghi Pius IX let build by Luigi Poletti two twin buildings that–together with the dolphins' fountain–provided a scenic entrance to the Leonine city.[34]They have the same late neoclassical style as the Manifattura dei Tabacchi ("Tobaccos factory") in piazza Mastai in Trastevere,[34]erected by Antonio Sarti a few years later.[35] The southern one lay between the south side of Borgo Vecchio and Borgo Santo Spirito.[34]

In 1867, a bomb placed in the Palazzo Serristori (at that time a barrack of the pontifical army) in Borgo Vecchio killed many zuavi (papal soldiers).[36] The perpetrators, Giuseppe Monti and Gaetano Tognetti, two Romans seeking the unification of their city with the Kingdom of Italy, were hanged.[36]

During the 19th century, several buildings of the eastern part of the street until Piazza Scossacavalli underwent restructuring, while the western part could keep its character.[37] At the eve of its disappearance, Borgo Vecchio was a quiet and secluded quarter road, lacking the artistic buildings and the shops of the nearby Borgo Nuovo.[16]

The central part of Borgo with the spina delimited by Borgo Vecchio and Borgo Nuovo in Rome's map of Giambattista Nolli (1748)

Between 1934 and 1936, when the project of Via della Conciliazione was developed, the architects Marcello Piacentini and Attilio Spaccarelli chose to give to the new road the alignment of Borgo Vecchio, and not of the nearby Borgo Nuovo,[38] which had been aligned between the now disappeared tower of Alexander VI near the Ponte Sant'Angelo and the bronze gate of the Vatican, and had a slope of 6 degrees with respect to the old Saint Peter.[39] This resolution, taken because of reasons of perspective and to avoid the demolition of the Palazzo dei Penitenzieri,[40] facing the south side of Piazza Scossacavalli and parallel to the south side of Borgo Vecchio, allowed for survival some among the road's main buildings, such as the palazzi Cesi-Armellini (although mutilated) and Serristori.[28] Due to that, while the spina, with the whole north side of Borgo Vecchio, was demolished between 29 October 1936 and 8 October 1937,[41] the south side of the road partially exists still today, although in a totally different context.[28]

Notable Buildings and landmarks

[edit]

The east entrance to Borgo in the 1930s. Borgo Vecchio is the road left of Palazzo Sauve, the building adorned with the wall fountain

- Palazzo Sauve (demolished)

- Palazzo delle Prigioni di Borgo (demolished, elements reused)

- Oratorio di San Sebastiano Scossacavalli (demolished)

- Palazzo Cesi-Armellini (partially demolished)

- Palazzo Serristori

- San Lorenzo in Piscibus (partially demolished)

- Palazzo Alicorni (demolished and rebuilt)

- ^ a b Delli 1988, p. 199.

- ^ Cambedda 1990, p. 47.

- ^ Delli 1988, p. 194.

- ^ a b Borgatti 1926, p. 291.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gigli 1990, p. 20.

- ^ a b Castagnoli et al. 1958, p. 363.

- ^ a b c Delli 1988, p. 193.

- ^ a b c Castagnoli et al. 1958, p. 241.

- ^ Gigli 1990, p. 9.

- ^ Borgatti 1926, p. 59.

- ^ Borgatti 1926, p. 60.

- ^ Borgatti 1926, p. 61.

- ^ a b Gigli 1990, p. 21.

- ^ Gigli 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Gigli 1990, p. 25.

- ^ a b Cambedda 1990, p. 61-2.

- ^ Gnoli 1939, p. 40, sub voce.

- ^ a b c Borgatti 1926, p. 159.

- ^ Cambedda 1990, p. 58.

- ^ Gigli 1990, p. 130.

- ^ a b c Gigli 1990, p. 88.

- ^ a b Gigli 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Borgatti 1926, p. 162.

- ^ Borgatti 1926, p. 163.

- ^ Borgatti 1926, p. 164.

- ^ a b Castagnoli et al. 1958, p. 419.

- ^ a b c Borgatti 1926, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Benevolo 2004, p. 86.

- ^ Gigli 1992, p. 136.

- ^ Gigli 1992, p. 138.

- ^ Gigli 1992, p. 154.

- ^ a b Gigli 1990, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Gigli 1990, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e Gigli 1990, p. 72.

- ^ Delli 1988, p. 604.

- ^ a b Gigli 1992, p. 102.

- ^ Cambedda 1990, p. 57.

- ^ Gigli 1990, p. 78.

- ^ Benevolo 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Gigli 1992, p. 74-78.

- ^ Gigli 1990, p. 33.

- Borgatti, Mariano (1926). Borgo e S. Pietro nel 1300 - 1600 - 1925 (in Italian). Roma: Federico Pustet.

- Ceccarelli, Giuseppe (Ceccarius) (1938). La "Spina" dei Borghi (in Italian). Roma: Danesi.

- Gnoli, Umberto (1939). Topografia e toponomastica di Roma medioevale e moderna (in Italian). Roma: Staderini.

- Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Cecchelli, Carlo; Giovannoni, Gustavo; Zocca, Mario (1958). Topografia e urbanistica di Roma (in Italian). Bologna: Cappelli.

- Delli, Sergio (1988). Le strade di Roma (in Italian). Roma: Newton & Compton.

- Gigli, Laura (1990). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Vol. Borgo (I). Fratelli Palombi Editori, Roma. ISSN 0393-2710.

- Gigli, Laura (1992). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Vol. Borgo (II). Fratelli Palombi Editori, Roma. ISSN 0393-2710.

- Cambedda, Anna (1990). La demolizione della Spina dei Borghi (in Italian). Fratelli Palombi Editori, Roma.

- Benevolo, Leonardo (2004). San Pietro e la città di Roma (in Italian). Laterza, Bari. ISBN 8842072362.