Bugle call (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Short military tune or signal

A French Marine plays the bugle during the Gulf War, in March 1991.

A bugle call is a short tune, originating as a military signal announcing scheduled and certain non-scheduled events on a military installation, battlefield, or ship. Historically, bugles, drums, and other loud musical instruments were used for clear communication in the noise and confusion of a battlefield. Naval bugle calls were also used to command the crew of many warships (signaling between ships being by flaghoist, semaphore, signal lamp or other means).

A defining feature of a bugle call is that it consists only of notes from a single overtone series. This is in fact a requirement if it is to be playable on a bugle or equivalently on a trumpet without moving the valves. (If a bandsman plays calls on a trumpet, for example, one particular key may be favored or even prescribed, such as: all calls to be played with the first valve down.)

Bugle calls typically indicated the change in daily routines of camp. Every duty around camp had its own bugle call, and since cavalry had horses to look after, they heard twice as many signals as regular infantry. "Boots and Saddles" was the most imperative of these signals and could be sounded without warning at any time of day or night, signaling the men to equip themselves and their mounts immediately. Bugle calls also relayed commanders' orders on the battlefield, signaling the troops to Go Forward, To the Left, To the Right, About, Rally on the Chief, Trot, Gallop, Rise up, Lay down, Commence Firing, Cease Firing, Disperse, and other specific actions.[1]

The military use of signal instruments dates to ancient times. The Romans used a form of bugle in their Legions.[2] Records show the use of an early bugle in Hanover by 1758,[3] and the British infantry introduced the Halbmondbläser in 1764.[4] The bugle gained widespread use in horse mounted units, where the more common signals of drums and fifes were impractical. At the 1776 Battle of Harlem Heights, the use of British bugle calls was taken as an insult by United States forces, who mistook them for hunting calls.

The bugle became more common with United States units during the War of 1812.[5] Through the 19th century, the bugle gradually replaced the fife. By the time of the United States Civil War, each company was allotted two buglers.[2]

Military use of bugles waned as new technology provided improved methods of field communication, but bugle calls continue to be used as traditional signals that mark daily events or special ceremonies. United States Army posts, for example, play Reveille at the start of a work day. In addition, the use of bugles and bugle calls is maintained in traditional Drum and bugle corps and some drum corps.

Memorial Stained Glass window, Class of 1934, Royal Military College of Canada showing Officer Cadet playing the Bugle call for Last Post or The Rouse

Norman Lindsay, The trumpet calls, World War I Australian recruitment poster

- "Adjutant's Call": Indicates that the adjutant is about to form the guard, battalion, or regiment.

- "Alarm" (as played by Sam Jaffe near the end of Gunga Din)

- "Assembly": Signals troops to assemble at a designated place.

- "Attention": Sounded as a warning that troops are about to be called to attention.

- "Boots and Saddles": Sounded for mounted troops to mount and take their place in line.

- "Call to Quarters": Signals all personnel not authorized to be absent to return to their quarters for the night.

- "Charge": Signals troops to execute a charge, or gallop forward into harm's way with deadly intent.

- "Church Call": Signals that religious services are about to begin.

The call may also be used to announce the formation of a funeral escort from a selected military unit. - "Drill Call": Sounds as a warning to turn out for drill.

- "Fatigue Call": Signals all designated personnel to report for fatigue duty.

- "Fire Call": Signals that there is a fire on the post or in the vicinity. The call is also used for fire drill.

- "First Call": Sounds as a warning that personnel will prepare to assemble for a formation.

- This call is also used in horse racing, where it is known as Call to the Post. In that context, it indicates that jockeys need to have their mounts in position to be loaded into the starting gate.

- "First Sergeant's Call": Signals that the First Sergeant is about to form the company.

- "Guard Mount": Sounds as a warning that the guard is about to be assembled for guard mount.

- "Last Post": Used at Commonwealth of Nations military funerals and ceremonies commemorating those who have been killed in a war.

- "Mail Call": Signals personnel to assemble for the distribution of mail.

- "Mess Call": Signals mealtime.

- "Officers Call": Signals all officers to assemble at a designated place.

- "Pay Call": Signals that troops will be paid.

- "Recall": Signals duties or drills to cease.

- "Retreat": Formerly used to signal troops to retreat. Now used to signal the end of the official day.[6] This bugle call is very close to Sunset used in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth realms. (This call is also used to introduce Act 3 of La damnation de Faust by Hector Berlioz.) In the U.S. Army, it is signaled right before To The Colors.

- "Reveille": Signals the troops to awaken for morning roll call.[7] In the U.S. Army, it accompanies the raising of the flag, thus representing the official beginning of the new day.[6]

- "The Rouse": Used in Commonwealth nations to signal soldiers to get out of bed (as distinct from Reveille, which signals the troops to awaken).

- "School Call": Signals school is about to begin.

- Sick Call: Signals all troops needing medical attention to report to the dispensary.

- "Stable Call": Signals troops to feed and water horses. Lyrics dating to 1852 Sumner's March to New Mexico: "Come off to the stables, all if you are able, and give your horses some oats and some corn; For if you don’t do it, the colonel will know it, And then you will rue it, as sure’s you’re born."[_citation needed_]

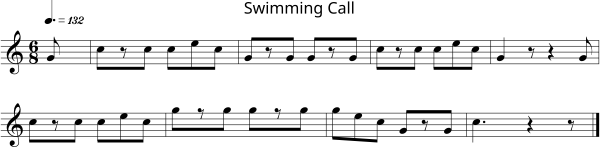

- "Swimming Call": Signals the start of the swimming period.

- "Taps": Signals that unauthorized lights are to be extinguished. This is the last call of the day.[6] The call is also sounded at the completion of a U.S. military funeral ceremony.

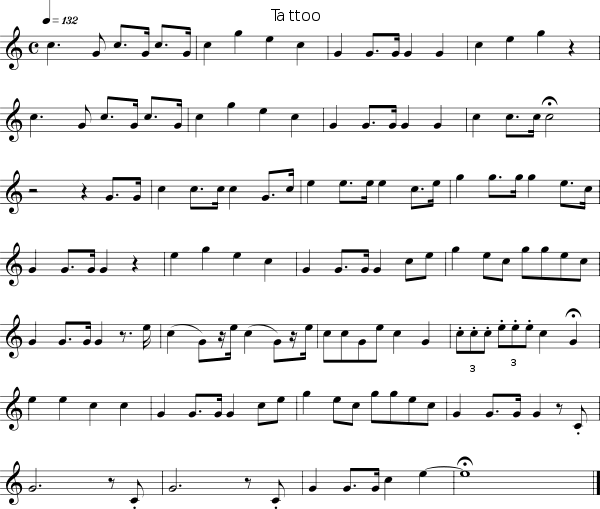

- "Tattoo": Signals that all light in squad rooms be extinguished and that all loud talking and other disturbances be discontinued within 15 minutes.

- "To Arms": Signals all troops to fall under arms at designated places without delay.

- "To The Colors" (or "To the Color"): In the United States, it is used to render honors to the nation. It is used when no band is available to render honors, or in ceremonies requiring honors to the nation more than once. "To the Colors" commands all the same courtesies as the National Anthem. The most common use of "To The Colors" is when it is sounded immediately following "Retreat". During this use of the call, the flag is lowered.

Many of the familiar calls have had words made up to fit the tune. For example, the U.S. "Reveille" goes:

I can't get 'em up,

I can't get 'em up,

I can't get 'em up this morning;

I can't get 'em up,

I can't get 'em up,

I can't get 'em up at all!

The corporal's worse than the privates,

The sergeant's worse than the corporals,

Lieutenant's worse than the sergeants,

And the captain's worst of all!

< repeat top six lines >

and the U.S. "Mess Call":

Soupy, soupy, soupy, without a single bean:

Coffee, coffee, coffee, without a speck of cream:

Porky, porky, porky, without a streak of lean.[8]

and the U.S. "Assembly":

There's a soldier in the grass

With a bullet up his ass

Take it out, take it out

Like a good Girl Scout!

and the U.S. "Taps"

Day is done

Gone the sun

From the lake, from the hills, from the sky

All is well, safely rest

God is nigh

Irving Berlin wrote a tune called, "Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning". In a filmed version of his musical, This Is the Army, he plays a World War I doughboy whose sergeant exhorts him with this variant of words sung to "Reveille": "Ya gotta get up, ya gotta get up, ya gotta get up this morning!" after which Berlin sang the song.

"Taps" has been used frequently in popular media, both sincerely (in connection with actual or depicted death) and humorously (as with a "killed" cartoon character). It is the title of a 1981 movie of the same name.

"First call" is best known for its use in thoroughbred horse racing, where it is also known as the "Call to the Post". It is used to herald (or summon) the arrival of horses onto the track for a race.

Another popular use of the "Mess Call" is a crowd cheer at football or basketball games. The normal tune is played by the band, with a pause to allow the crowd to chant loudly, "Eat 'em up! Eat 'em up! Rah! Rah! Rah!"

Early solid state Bally pinball tables played two bugle calls on their chime units. First Call was used as the game start tune and To the Colors for game over.

- Bugle calls of the Bersaglieri Corps (Italian Army)

- Bugle calls of the Norwegian Army

- Bugle and trumpet calls of the Mexican Armed Forces

- Military rites

- Ruffles and flourishes

- ^ Upton, Emory (1867). A New System of Infantry Tactics. pp. (appendix).

- ^ a b Keating, Gerald (1993). "Buglers and Bugle Calls in the U.S. Army". Army History (27). U.S. Army Center of Military History: 16–18. JSTOR 26304103. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

- ^ "An Introductory History of the Bugle From its Early Origins to the Present Day". Taps Bugler. 2019. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

- ^ "The military bugle". 2021. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

- ^ Dobney, Jayson Kerr (2004). "Military Music in American and European Traditions". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

- ^ a b c "Reveille, Retreat, and Taps" (PDF). Defense Logistics Agency. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Army Bands – Bugle calls – Reveille". Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Sperber, Hans (1951). "Bugle Calls". Midwest Folklore. 1 (3). Indiana University Press: 167–170. JSTOR 4317288.

Rush, Robert S. (2010). NCO Guide. Stackpole Books. p. 328. ISBN 978-0811742276.

British Army Bugle Calls (Duke of Edinburgh's Royal Regiment)

Shenkle, Kathryn, “The History of Taps,” Air National Guard Family Guide, p. 40