Carrack (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

14th–17th century masted sailing ship

Not to be confused with Karak.

The large carrack, thought to be the Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai, and other Portuguese carracks of various sizes. From painting, attributed to either Gregório Lopes or Cornelis Antoniszoon, showing voyage of the marriage party of Princess Beatrice of Portugal, Duchess of Savoy in 1521.

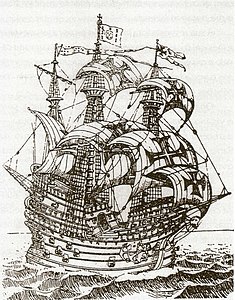

c. 1558 painting of a large carrack attributed to Pieter Bruegel the Elder

A carrack (Portuguese: nau; Spanish: nao; Catalan: carraca; Croatian: karaka) is a three- or four-masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal and Spain. Evolving from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for European trade from the Mediterranean to the Baltic and quickly found use with the newly found wealth of the trade between Europe and Africa and then the trans-Atlantic trade with the Americas. In their most advanced forms, they were used by the Portuguese and Spaniards for trade between Europe, Africa and Asia starting in the late 15th century, before being gradually superseded in the late 16th and early 17th centuries by the galleon.

In its most developed form, the carrack was a carvel-built ocean-going ship: large enough to be stable in heavy seas, and capacious enough to carry a large cargo and the provisions needed for very long voyages. The later carracks were square-rigged on the foremast and mainmast and lateen-rigged on the mizzenmast. They had a high rounded stern with aftcastle, forecastle and bowsprit at the stem. As the predecessor of the galleon, the carrack was one of the most influential ship designs in history; while ships became more specialized in the following centuries, the basic design remained unchanged throughout this period.[1]

Replica of a small 15th-century or 16th-century carrack at Vila do Conde, Portugal

Naval battle involving carracks and galleys

English carrack was loaned in the late 14th century, via Old French caraque, from carraca, a term for a large, square-rigged sailing vessel used in Spanish, Italian and Middle Latin.

These ships were called carraca in Portuguese and Genoese, carraca in Spanish, caraque or nef in French, and kraak in Dutch.

The origin of the term carraca is unclear, perhaps from Arabic qaraqir "merchant ship", itself of unknown origin (maybe from Latin carricare "to load a car" or Greek καρκαρίς "load of timber") or the Arabic القُرْقُورُ (al-qurqoor) and from thence to the Greek κέρκουρος (kerkouros) meaning approximately "lighter" (barge) literally, "shorn tail", a possible reference to the ship's flat stern). Its attestation in Greek literature is distributed in two closely related lobes. The first distribution lobe, or area, associates it with certain light and fast merchantmen found near Cyprus and Corfu. The second is an extensive attestation in the Oxyrhynchus corpus, where it seems most frequently to describe the Nile barges of the Ptolemaic pharaohs. Both of these usages may lead back through the Phoenician to the Akkadian kalakku, which denotes a type of river barge. The Akkadian term is assumed to be derived from a Sumerian antecedent.[2] A modern reflex of the word is found in Arabic and Turkish kelek "raft; riverboat".[3]

Three- and four-masted carracks

16th-century depiction of a Portuguese nau

By the Late Middle Ages, the cog and cog-like square-rigged vessels equipped with a rudder at the stern, were widely used along the coasts of Europe, from the Mediterranean, to the Baltic. Given the conditions of the Mediterranean, galley type vessels were extensively used there, as were various two masted vessels, including the caravels with their lateen sails. These and similar ship types were familiar to Portuguese navigators and shipwrights. As the Portuguese and Spaniards gradually extended their trade ever further south along Africa's Atlantic coast and islands during the 15th century, they needed larger, more durable and more advanced sailing ships for their long oceanic ventures. Gradually, they developed their own models of oceanic carracks from a fusion and modification of aspects of the ship types they knew operating in both the Atlantic and Mediterranean, generalizing their use in the end of the century for inter-oceanic travel with a more advanced form of sail rigging that allowed much improved sailing characteristics in the heavy winds and waves of the Atlantic Ocean and a hull shape and size that permitted larger cargoes. In addition to the average tonnage naus, some naus (carracks) were also built in the reign of John II of Portugal, but were widespread only after the turn of the century. The Portuguese carracks were usually very large ships for their time, often over 1000 tons displacement,[4] and having the future naus of the India run and of the China and Japan trade, also other new types of design.

A typical three-masted carrack such as the São Gabriel had six sails: bowsprit, foresail, mainsail, mizzensail and two topsails.

Replica of Dubrovačka karaka (Dubrovnik Carrack), used between the 14th and the 17th century for cargo transport in the Republic of Ragusa (present-day Croatia)

In the Republic of Ragusa, a kind of a three or four masted carrack called Dubrovačka karaka (Dubrovnik Carrack) was used between the 14th and the 17th century for cargo transport.

In the middle of the 16th century, the first galleons were developed from the carrack. The galleon design came to replace that of the carrack although carracks were still in use as late as the middle of the 17th century due to their larger cargo capacity.

Starting in 1498, Portugal initiated for the first time direct and regular exchanges between Europe and India—and the rest of Asia thereafter—through the Cape Route, a voyage that required the use of more substantial vessels, such as carracks, due to its unprecedented duration, about six months.

On average, four carracks connected Lisbon to Goa carrying gold to purchase spices and other exotic items, but mainly pepper. From Goa, one carrack went on to Ming China in order to purchase silks. Starting in 1541, the Portuguese began trading with Japan, exchanging Chinese silk for Japanese silver; in 1550 the Portuguese Crown started to regulate trade to Japan, by leasing the annual "captaincy" to Japan to the highest bidder at Goa, in effect conferring exclusive trading rights for a single carrack bound for Japan every year. In 1557 the Portuguese acquired Macau to develop this trade in partnership with the Chinese. That trade continued with few interruptions until 1638, when it was prohibited by the rulers of Japan on the grounds that the ships were smuggling Catholic priests into the country. The Japanese called Portuguese carracks "Black Ships" (kurofune), referring to the colour of the ship's hulls. This term would eventually come to refer to any Western vessel, not just Portuguese.

Ottoman barca from Piri Reis' map

The Islamic world also built and used carracks, or at least carrack-like ships, in the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. A picture of an Ottoman barca on Piri Reis' map shows a deep-hulled ship with a tall forecastle and a lateen sail on the mizzenmast.[5]: 329–330 The harraqa (Saracen: karaque) was a type of ship used to hurl explosives or inflammable materials (firebomb in earthenware pots, naphtha, fire arrows). From the context of Islamic texts, there are two types of harraqa: The cargo ship and the smaller longship (galley-like) that was used for fighting. It is unclear whether the nomenclature harraqa has a connection with European carraca (carrack), or whether one influences the other. One Muslim harraqa named Mogarbina was captured by the Knights of St. John in 1507 from the Ottoman Turks and renamed Santa Maria.[5]: 343–348 Gujarati ships are usually called naos (carracks) by the Portuguese. Gujarati naos operated between Malacca and the Red Sea, and were often larger than Portuguese carracks. The Bengalis also used carracks, sometimes called naos mauriscas (Moorish carracks) by the Portuguese. Arabs merchants of Mecca apparently used carracks too, since Duarte Barbosa noted that the Bengali people have "great naos after the fashion of Mecca".[6]: 605–606, 610

- Santa María, in which Christopher Columbus made his first voyage to America in 1492.

- Gribshunden, flagship of the Danish-Norwegian King Hans, built in the Low Countries 1485 and served the Danish-Norwegian crown until sinking in June 1495.[7][8]

- São Gabriel, flagship of Vasco da Gama, in the 1497 Portuguese expedition from Europe to India by circumnavigating Africa.

- Flor do Mar or Flor de la Mar, as it was called, served over nine years in the Indian Ocean, sinking in 1512 with Afonso de Albuquerque after the conquest of Malacca with a huge booty, making it one of the legendary lost treasures.

- Victoria, the first ship in history to circumnavigate the globe (1519 to 1522), and the only survivor of Magellan's expedition for Spain.

- La Dauphine, Verrazzano's ship to explore the Atlantic coast of North America in 1524.

- Grande Hermine, in which Jacques Cartier first navigated the Saint Lawrence River in 1535. The first European ship to sail on this river past the Gulf.

- Santo António, or St. Anthony, the personal property of King John III of Portugal, wrecked off Gunwalloe Bay in 1527, the salvage of whose cargo almost led to a war between England and Portugal.

- Great Michael, a Scottish ship, at one time the largest in Europe.

- Mary Rose, Henri Grâce à Dieu and Peter Pomegranate, built during the reign of King Henry VIII of England — English military carracks like these were often called great ships.

- Grace Dieu, commissioned by King Henry V of England. One of the largest ships in the world at the time.

- Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai, a war ship built in India by the Portuguese

- Santa Anna, a particularly modern design commissioned by the Knights Hospitaller in 1522 and sometimes hailed as the first armoured ship.

- Jesus of Lübeck, chartered to a group of merchants in 1563 by Queen Elizabeth I of England. Jesus of Lübeck became involved in the Atlantic slave trade under John Hawkins.

- Madre de Deus, built in Lisbon during 1589, she was one of the world's largest ships. She was captured by the English off Flores Island in 1592 with an enormously valuable cargo from the East Indies that is still considered the second-largest treasure ever captured.

- Cinco Chagas, presumed to have been the largest and richest ship to ever sail to and from the Indies until it exploded and sank at the action of Faial in 1594.

- Santa Catarina, Portuguese carrack which was seized by the Dutch East India Company off Singapore in 1603.

- Nossa Senhora da Graça, Portuguese carrack sunk in a Japanese attack near Nagasaki in 1610

- Peter von Danzig, ship of the Hanseatic League in 1460s–1470s.

- La Gran Carracca, the ship of the Order of St. John during their rule over Malta.[9]

- Bom Jesus, a Portuguese ship that disappeared in 1533 after sailing from Lisbon. The well preserved shipwreck was discovered in 2008 on the coast of Namibia, along with its cargo of assorted copper ingots, elephant ivory and over 2000 gold and silver coins.

Small 16th-century carrack- [

](/wiki/File:Frol%5Fde%5Fla%5Fmar%5Fin%5Froteiro%5Fde%5Fmalaca.jpeg "Famous Portuguese nau Flor de la Mar (launched in 1501 or 1502), in the 16th-century "Roteiro de Malaca"")

](/wiki/File:Frol%5Fde%5Fla%5Fmar%5Fin%5Froteiro%5Fde%5Fmalaca.jpeg "Famous Portuguese nau Flor de la Mar (launched in 1501 or 1502), in the 16th-century "Roteiro de Malaca"")

Famous Portuguese nau Flor de la Mar (launched in 1501 or 1502), in the 16th-century "Roteiro de Malaca"

A replica of Nao Victoria, in 1522 the first ship to circumnavigate the globe and the only Magellan ship to return

Columbus' Ships (G.A. Closs, 1892): the Santa Maria and Pinta are shown as carracks; the Niña (left) as a caravel.

Model of the carrack Madre de Deus, in the Maritime Museum, Lisbon. Built based on another design, later in Portugal (1589), she was one of the largest ship in the world in her time. She had seven decks.

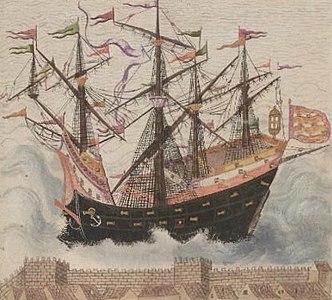

Portuguese carrack, as depicted in a map made in 1565

Japanese depiction of a Portuguese carrack, dubbed kurofune (black ship)- [

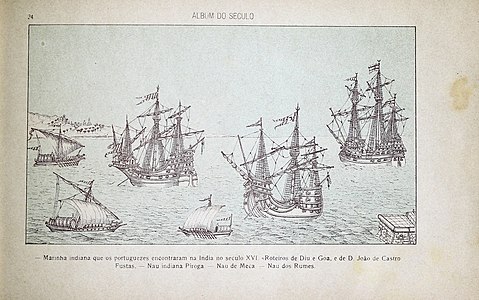

](/wiki/File:Fustas,%5FNau%5FIndiana%5FPiroga,%5FNau%5Fde%5FMeca%5F%26%5FNau%5Fde%5FRumes.jpg "Carracks of the Indian Ocean: Indian carrack "Piroga" — Carrack of Mecca — Carrack of Rumes (Ottoman)")

](/wiki/File:Fustas,%5FNau%5FIndiana%5FPiroga,%5FNau%5Fde%5FMeca%5F%26%5FNau%5Fde%5FRumes.jpg "Carracks of the Indian Ocean: Indian carrack "Piroga" — Carrack of Mecca — Carrack of Rumes (Ottoman)")

Carracks of the Indian Ocean: Indian carrack "Piroga" — Carrack of Mecca — Carrack of Rumes (Ottoman)

A four-masted Turkish carrack, 1586

The Italian word caracca and derivative words are popularly used in reference to a cumbersome individual, to an old vessel, or to a vehicle in a very bad condition.[9]The Portuguese form of "carrack", nau, is used as its unique unit in the Civilization V and Civilization VI strategy game.

- ^ Konstam, A. (2002). The History of Shipwrecks. New York: Lyons Press. pp. 77–79. ISBN 1-58574-620-7.

- ^ Bosworth, C. Edmund (1991). "Some remarks on the terminology of irrigation practices and hydraulic constructions in the eastern Arab and Iranian worlds in the third-fifth centuries A.H.". Journal of Islamic Studies. 2 (1): 78–85. doi:10.1093/jis/2.1.78.

- ^ Gong, Y (1990). "kalakku: Überlegungen zur Mannigfaltigkeit der Darstellungsweisen desselben Begriffs in der Keilschrift anhand des Beispiels kalakku". Journal of Ancient Civilizations. 5: 9–24. ISSN 1004-9371.

- ^ Braudel, F (1979). The Structures of Everyday Life. Harper & Row. p. 423. ISBN 0060148454.

- ^ a b Agius, Dionisius A. (2007). Classic Ships of Islam: From Mesopotamia to the Indian Ocean. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 978-9004277854.

- ^ Manguin, Pierre-Yves. 2012. "Asian shipbuilding traditions in the Indian Ocean at the dawn of European expansion", in: Om Prakash and D. P. Chattopadhyaya (eds), History of science, philosophy, and culture in Indian Civilization, Volume III, Part 7: The trading world of the Indian Ocean, 1500–1800, pp. 597–629. Delhi, Chennai, Chandigarh: Pearson.[_ISBN missing_]

- ^ Foley, Brendan (2024-01-31). "Interim Report on Gribshunden (1495) Excavations: 2019–2021". Acta Archaeologica. 94 (1): 132–145. doi:10.1163/16000390-09401052. ISSN 0065-101X.

- ^ Hansson, Anton; Linderson, Hans; Foley, Brendan (August 2021). "The Danish royal flagship gribshunden – Dendrochronology on a late medieval carvel sunk in the Baltic Sea". Dendrochronologia. 68: 125861. Bibcode:2021Dendr..6825861H. doi:10.1016/j.dendro.2021.125861. ISSN 1125-7865.

- ^ a b Cassar Pullicino, Joseph (October–December 1949). "The Order of St. John in Maltese folk-memory" (PDF). Scientia. 15 (4): 174. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2016.

- Kirsch, Peter (1990). The Galleon. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-546-2.

- Nair, V. Sankaran (2008). Kerala Coast: A Byway in History. (Carrack: Word Lore). Trivandrum: Folio. ISBN 978-81-906028-1-5.

Look up carrack in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.