Cyril M. Kornbluth (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

American science fiction author (1923–1958)

| Cyril M. Kornbluth | |

|---|---|

Kornbluth c. 1955 Kornbluth c. 1955 |

|

| Born | (1923-07-02)July 2, 1923New York City, United States |

| Died | March 21, 1958(1958-03-21) (aged 34)Levittown, New York, United States |

| Pen name | Cecil CorwinS.D. GottesmanEdward J. BellinKenneth FalconerWalter C. DaviesSimon EisnerJordan Park |

| Occupation | Novelist short story author editor |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Spouse | Mary Byers |

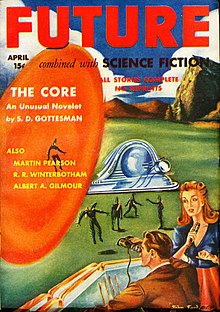

An early Kornbluth novelette, "The Core", was the cover story for the April 1942 issue of Future. It carried the "S. D. Gottesman" byline, a pseudonym Kornbluth used mainly for collaborations with Frederik Pohl or Robert A. W. Lowndes

The opening installment of Mars Child, by Kornbluth and Judith Merril, took the cover of the May 1951 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction

A year later, the first installment of Gravy Planet (The Space Merchants), by Kornbluth and Frederik Pohl, was also cover-featured on Galaxy

Another Kornbluth-Merril collaboration, the novelette "Sea-Change", was the cover story for the second issue of Dynamic Science Fiction in 1953. It has apparently never been reprinted.

Another Kornbluth-Pohl collaboration, Gladiator-at-Law, took the cover of the June 1954 Galaxy Science Fiction in 1954, illustrated by Ed Emshwiller

The last Kornbluth-Pohl sf novel, "Wolfbane", was serialized in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1957, with a cover illustration by Wally Wood.

Cyril M. Kornbluth (July 2, 1923[1] – March 21, 1958) was an American science fiction author and a member of the Futurians. He used a variety of pen-names, including Cecil Corwin, S. D. Gottesman, Edward J. Bellin, Kenneth Falconer, Walter C. Davies, Simon Eisner, Jordan Park, Arthur Cooke, Paul Dennis Lavond, and Scott Mariner.[2]

Kornbluth was born and grew up in the uptown Manhattan neighborhood of Inwood, in New York City.[3] He was of Polish-Jewish descent,[4] the son of a World War I veteran and grandson of a tailor, a Jewish immigrant from Galicia.[5]

The "M" in Kornbluth's name may have been in tribute to his wife, Mary Byers;[6] Kornbluth's colleague and collaborator Frederik Pohl confirmed Kornbluth's lack of any actual middle name in at least one interview.[7]

According to his widow, Kornbluth was a "precocious child", learning to read by the age of three and writing his own stories by the time he was seven. He graduated from high school at thirteen, received a CCNY scholarship at fourteen, and was "thrown out for leading a student strike" without graduating.[5]

As a teenager, he became a member of the Futurians, an influential group of science fiction fans and writers. While a member of the Futurians, he met and became friends with Frederik Pohl, Donald A. Wollheim, Robert A. W. Lowndes, and his future wife Mary Byers. He also participated in the Fantasy Amateur Press Association.

Kornbluth served in the US Army during World War II (European theatre).[8] He received a Bronze Star for his service in the Battle of the Bulge, where he served as a member of a heavy machine gun crew. Upon his discharge, he returned to finish his education at the University of Chicago under the G.I. Bill.[8] While living in Chicago he also worked at Trans-Radio Press, a news wire service. In 1951 he started writing full-time,[5] returning to the East Coast where he collaborated on novels with his old Futurian friends Frederik Pohl and Judith Merril.

Kornbluth began writing at 15. His first solo story, "The Rocket of 1955", was published in Richard Wilson's fanzine Escape (Vol. 1, No 2, August 1939); his first collaboration, "Stepsons of Mars," written with Richard Wilson and published under the name "Ivar Towers", appeared in the April 1940 Astonishing. His other short fiction includes "The Little Black Bag", "The Marching Morons", "The Altar at Midnight", "MS. Found in a Chinese Fortune Cookie", "Gomez" and "The Advent on Channel Twelve".

"The Little Black Bag" was first adapted for television live on the television show Tales of Tomorrow on May 30, 1952. It was later adapted for television by the BBC in 1969 for its Out of the Unknown series. In 1970, the same story was adapted by Rod Serling for an episode of his Night Gallery series. This dramatization starred Burgess Meredith as the alcoholic Dr. William Fall, who had long lost his doctor's license and become a homeless alcoholic. He finds a bag containing advanced medical technology from the future, which, after an unsuccessful attempt to pawn it, he uses benevolently.

"The Marching Morons" is a look at a far future in which the world's population consists of five billion idiots and a few million geniuses – the precarious minority of the "elite" working desperately to keep things running behind the scenes. In his introduction to The Best of C. M. Kornbluth, Pohl states that "The Marching Morons" is a direct sequel to "The Little Black Bag": it is easy to miss this, as "Bag" is set in the contemporary present while "Morons" takes place several centuries from now, and there is no character who appears in both stories. The titular black bag in the first story is actually an artifact from the time period of "The Marching Morons": a medical kit filled with self-driven instruments enabling a far-future moron to "play doctor". A future Earth similar to "The Marching Morons" – a civilisation of morons protected by a small minority of hidden geniuses – is used again in the final stages of Kornbluth & Pohl's Search the Sky.[9]

"MS. Found in a Chinese Fortune Cookie" (1957) is supposedly written by Kornbluth using notes by "Cecil Corwin", who has been declared insane and incarcerated, and who smuggles out in fortune cookies the ultimate secret of life. This fate is said to be Kornbluth's response to the unauthorized publication of "Mask of Demeter" (as by "Corwin" and "Martin Pearson" (Donald A. Wollheim)) in Wollheim's anthology Prize Science Fiction in 1953.[10]

Biographer Mark Rich describes the 1958 story "Two Dooms" as one of several stories which are "concern[ed] with the ethics of theoretical science" and which "explore moral quandaries of the atomic age":

"Two Dooms" follows atomic physicist Edward Royland on his accidental journey into an alternative universe where the Nazis and Japanese rule a divided United States. In his own world, Royland debated whether to delay progress at the Los Alamos nuclear research site or to help the atomic bomb achieve its terrifying result. Encountering both a slave village and a concentration camp in the alternative America, he comes to grips with the idea of life under bondage.[9]

Many of Kornbluth's novels were written as collaborations: either with Judith Merril (using the pseudonym Cyril Judd), or with Frederik Pohl. These include Gladiator-At-Law and The Space Merchants.[11] The Space Merchants contributed significantly to the maturing and to the wider academic respectability of the science fiction genre, not only in America but also in Europe.[12] Kornbluth also wrote several novels under his own name, including The Syndic and Not This August.

Kornbluth died at age 34 in Levittown, New York. On a day when he was due to meet with Bob Mills in New York City to interview for the position of editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction,[13] he was delayed because he had to shovel snow from his driveway. After running to meet his train following this delay, Kornbluth suffered a fatal heart attack on the platform of the station.[8]

A number of short stories remained unfinished at Kornbluth's death; these were eventually completed and published by Pohl. One of these stories, "The Meeting" (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November 1972), was the co-winner of the 1973 Hugo Award for Best Short Story; it tied with R. A. Lafferty's "Eurema's Dam."[14] Almost all of Kornbluth's solo SF stories have been collected as His Share of Glory: The Complete Short Science Fiction of C. M. Kornbluth (NESFA Press, 1997).

Personality and habits

[edit]

Frederik Pohl, in his autobiography The Way the Future Was, Damon Knight, in his memoir The Futurians, and Isaac Asimov, in his memoirs In Memory Yet Green and I. Asimov: A Memoir, all give descriptions of Kornbluth as a man of odd personal habits and eccentricities.

Kornbluth, for example, decided to educate himself by reading his way through an entire encyclopedia from A to Z; in the course of this effort, he acquired a great deal of esoteric knowledge that found its way into his stories, in alphabetical order by subject. When Kornbluth wrote a story that mentioned the ballista, an Ancient Roman weapon, Pohl knew that Kornbluth had finished the 'A's and had started on the 'B's.

According to Pohl, Kornbluth never brushed his teeth, and they were literally green.[_citation needed_] Deeply embarrassed by this, Kornbluth developed the habit of holding his hand in front of his mouth when speaking.

- Outpost Mars (1952) (with Judith Merril, writing as Cyril Judd), first published as a Galaxy serial entitled Mars Child (May–July 1951) and later reprinted as Galaxy novel No. 46 retitled Sin in Space (1961)

- Gunner Cade (1952) (with Judith Merril, writing as Cyril Judd), first published as an Astounding Science Fiction serial (March–May 1952)

- Takeoff (May 1952), later serialised in New Worlds (April–June 1954)

- The Space Merchants (April 1953) (with Frederik Pohl), first published as a Galaxy serial entitled Gravy Planet (June–August 1952)

- The Syndic (October 1953), later serialised in Science Fiction Adventures (December 1953-March 1954), entered the Prometheus Award Hall of Fame in 1986

- Search the Sky (February 1954) (with Frederik Pohl), later revised by Pohl (October 1985)

- Gladiator at Law (May 1955) (with Frederik Pohl), first published as a Galaxy serial (June–August 1954), later revised by Pohl (April 1986)

- Not This August (July 1955) (AKA Christmas Eve), later revised by Pohl (December 1981)

- Wolfbane (September 1959) (with Frederik Pohl), first published as a Galaxy serial (October–November 1957), later revised by Pohl (June 1986)

- The Explorers (1954)

- "Foreword", [Frederik Pohl]

- "Gomez"

- "The Mindworm", 1950

- "The Rocket of 1955", 1939

- "The Altar at Midnight", 1952

- "Thirteen O’Clock" [as by Cecil Corwin], (1941) "Peter Packer" series

- "The Goodly Creatures", 1952

- "Friend to Man", 1951

- "With These Hands", 1951

- "That Share of Glory", 1962

- The Mindworm and Other Stories (1955)

- "The Mindworm”, (1950)

- "Gomez”, 1954

- "The Rocket of 1955”, 1939

- "The Altar at Midnight”, 1952

- "The Little Black Bag”, 1950

- "The Goodly Creatures”, 1952

- "Friend to Man”, 1951

- "With These Hands”, 1951

- "That Share of Glory”, 1952

- "The Luckiest Man in Denv" [as by Simon Eisner], · 1952

- "The Silly Season”, 1950

- "The Marching Morons · nv Galaxy Apr ’51

- A Mile Beyond the Moon (1958) [abridged for its 1962 paperback reprint, see below]

- "Make Mine Mars”, 1952

- "The Meddlers”, 1953 [not in 1962 paperback]

- "The Events Leading Down to the Tragedy”, 1958

- "The Little Black Bag”, 1950 (related to "The Marching Morons")

- "Everybody Knows Joe”, 1953

- "Time Bum”, 1953

- "Passion Pills”, [original here] [not in 1962 paperback]

- "Virginia”, 1958

- "The Slave”, 1957 [not in 1962 paperback]

- "Kazam Collects" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "The Last Man Left in the Bar”, 1947 – "a confrontation between aliens and a magnetron technician, written with an audacious literary command"[9]

- "The Adventurer”, 1953

- "The Words of Guru" [as by Kenneth Falconer], 1941 – "an early but striking fantasy about a genius child acquiring supernatural power"[9]

- "Shark Ship" ["Reap the Dark Tide"], 1958

- "Two Dooms”, 1958 [not in 1962 paperback]

- The Marching Morons (and other Science Fiction Stories) (1959)

- "The Marching Morons”, 1951

- "Dominoes”, 1953

- "The Luckiest Man in Denv" [as by Simon Eisner], 1952

- "The Silly Season”, 1950

- "MS. Found in a Chinese Fortune Cookie”, 1957

- "The Only Thing We Learn”, 1949

- "The Cosmic Charge Account”, 1956

- "I Never Ask No Favors”, 1954

- "The Remorseful”, 1953

- The Wonder Effect (1962) (with Frederik Pohl)

- "Introduction”,

- "Critical Mass”, 1962

- "A Gentle Dying”, 1961

- "Nightmare with Zeppelins", 1958

- "Best Friend" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "The World of Myrion Flowers”, 1961

- "Trouble in Time" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1940

- "The Engineer”, 1956

- "Mars-Tube [as by S. D. Gottesman]”, 1941

- "The Quaker Cannon”, 1961

- Best Science Fiction Stories of C. M. Kornbluth (1968)

- "Introduction”, [Edmund Crispin]

- "The Unfortunate Topologist”, 1957 (poem)

- "The Marching Morons”, 1951

- "The Altar at Midnight”, 1952

- "The Little Black Bag”, 1950

- "The Mindworm”, 1950

- "The Silly Season”, 1950

- "I Never Ask No Favors”, 1954

- "Friend to Man”, 1951

- "The Only Thing We Learn”, 1949

- "Gomez”, 1954

- "With These Hands”, 1951

- "Theory of Rocketry”, 1958

- "That Share of Glory”, 1952

- Thirteen O'Clock and other Zero Hours (1970) (edited by James Blish) stories published originally as by "Cecil Corwin" plus "MS. Found in a Chinese Fortune Cookie" (see above)

- "Preface”, [James Blish]

- "Thirteen O’Clock [combined version of the "Peter Packer" stories, “Thirteen O’Clock” and “Mr. Packer Goes to Hell”, both 1941]”, [first combined appearance here]

- "The Rocket of 1955”, 1939

- "What Sorghum Says" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1941

- "Crisis!" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1942

- "The Reversible Revolutions" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1941

- "The City in the Sofa" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1941

- "The Golden Road" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1942

- "MS. Found in a Chinese Fortune Cookie”, 1957

- The Best of C. M. Kornbluth (1976)

- "An Appreciation”, [Frederik Pohl]

- "The Rocket of 1955”, 1939

- "The Words of Guru" [as by Kenneth Falconer], 1941

- "The Only Thing We Learn”, 1949

- "The Adventurer”, 1953

- "The Little Black Bag”, 1950

- "The Luckiest Man in Denv" [as by Simon Eisner], 1952

- "The Silly Season”, 1950

- "The Remorseful”, 1953

- "Gomez”, 1954

- "The Advent on Channel Twelve”, 1958

- "The Marching Morons”, 1951

- "The Last Man Left in the Bar”, 1957

- "The Mindworm”, 1950

- "With These Hands”, 1951

- "Shark Ship" [“Reap the Dark Tide”], 1958

- "Friend to Man”, 1951

- "The Altar at Midnight”, 1952

- "Dominoes”, 1953

- "Two Dooms”, 1958

Spider Robinson praised this collection, saying "I haven't enjoyed a book so much in years."[15] Mark Rich wrote, "Critics judging Kornbluth by this anthology, edited by Pohl, have seen a growing bitterness in his later stories. This reflects editorial choice more than reality, because Kornbluth also wrote delightful humor in his last years, in stories not collected here. These tales demonstrate Kornbluth's effective use of everyday individuals from a variety of ethnic backgrounds as well as his well-tuned ear for dialect."[9]

- Critical Mass (1977) (with Frederik Pohl)

- "Introduction”, (Pohl)

- "The Quaker Cannon”, 1961

- "Mute Inglorious Tam”, 1974

- "The World of Myrion Flowers”, 1961

- "The Gift of Garigolli”, 1974

- "A Gentle Dying”, 1961

- "A Hint of Henbane”, 1961

- "The Meeting”, 1972

- "The Engineer”, 1956

- "Nightmare with Zeppelins”, 1958

- "Critical Mass”, 1962

- "Afterword”, (Pohl)

- Before the Universe (1980) (with Frederik Pohl)

- "Mars-Tube" [as by S. D. Gottesman (with Frederik Pohl)], 1941

- "Trouble in Time" [as by S. D. Gottesman (with Frederik Pohl)], 1940

- "Vacant World" [as by Dirk Wylie (with Dirk Wylie, and Frederik Pohl)], 1940

- "Best Friend" [as by S. D. Gottesman (with Frederik Pohl)], 1941

- "Nova Midplane" [as by S. D. Gottesman (with Frederik Pohl)], 1940

- "The Extrapolated Dimwit" [as by S. D. Gottesman (with Frederik Pohl)], 1942

- Our Best: The Best of Frederik Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth (1987) (with Frederik Pohl)

- "Introduction”, (Pohl)

- "The Stories of the Sixties”, (Pohl, section introduction)

- "Critical Mass”, 1962

- "The World of Myrion Flowers”, 1961

- "The Engineer”, 1956

- "A Gentle Dying”, 1961

- "Nightmare with Zeppelins”, 1958

- "The Quaker Cannon”, 1961

- "The 60/40 Stories”, (Pohl, section introduction)

- "Trouble in Time" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1940

- "Mars-Tube" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "Epilogue to The Space Merchants”, (Pohl, section introduction)

- "Gravy Planet”, (extract from the magazine serial, not used in the book)

- "The Final Stories”, (Pohl, section introduction)

- "Mute Inglorious Tam”, 1974

- "The Gift of Garigolli”, 1974

- "The Meeting”, 1972

- "Afterword”, (Pohl)

- His Share of Glory: The Complete Short Science Fiction of C.M. Kornbluth (1997) – this includes almost all of Kornbluth's solo fiction, but does not include all of the collaborative pseudonymous works which were published among his earliest work between 1940 and 1942, some of which were published in Before the Universe (1980).

- "Cyril”, [Frederik Pohl]

- "Editor’s Introduction”, [Timothy P. Szczesuil]

- "That Share of Glory”, 1952

- "The Adventurer”, 1952

- "Dominoes”, 1953

- "The Golden Road" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1942

- "The Rocket of 1955”, 1939

- "The Mindworm”, 1950

- "The Education of Tigress McCardle”, 1957

- "Shark Ship" [“Reap the Dark Tide”], 1958

- "The Meddlers”, 1953

- "The Luckiest Man in Denv" [as by Simon Eisner], 1952

- "The Reversible Revolutions [as by Cecil Corwin], 1941

- "The City in the Sofa" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1941

- "Gomez”, 1954

- "Masquerade" [as by Kenneth Falconer], 1942

- "The Slave”, 1957

- "The Words of Guru" [as by Kenneth Falconer], 1941

- "Thirteen O’Clock" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1941

- "Mr. Packer Goes to Hell" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1941

- "With These Hands”, 1951

- "Iteration”, 1950

- "The Goodly Creatures”, 1952

- "Time Bum”, 1953

- "Two Dooms”, 1958

- "Passion Pills”, 1958

- "The Silly Season”, 1950

- "Fire-Power" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "The Perfect Invasion" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1942

- "The Adventurers”, 1955

- "Kazam Collects" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "The Marching Morons”, 1951

- "The Altar at Midnight”, 1952

- "Crisis!" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1942

- "Theory of Rocketry”, 1958

- "The Cosmic Charge Account”, 1956

- "Friend to Man”, 1951

- "I Never Ast No Favors”, 1954

- "The Little Black Bag”, 1950

- "What Sorghum Says" [as by Cecil Corwin], 1941

- "MS. Found in a Chinese Fortune Cookie”, 1957

- "The Only Thing We Learn”, 1949

- "The Last Man Left in the Bar”, 1957

- "Virginia”, 1958

- "The Advent on Channel Twelve”, 1958

- "Make Mine Mars”, 1952

- "Everybody Knows Joe”, 1953

- "The Remorseful”, 1953

- "Sir Mallory’s Magnitude" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "The Events Leading Down to the Tragedy”, 1958

- "King Cole of Pluto" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1940

- "No Place to Go" [as by Edward J. Bellin], 1941

- "Dimension of Darkness" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "Dead Center" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "Interference" [as by Walter C. Davies], 1941

- "Forgotten Tongue" [as by Walter C. Davies], 1941

- "Return from M-15" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1941

- "The Core" [as by S. D. Gottesman], 1942

Non-science fiction

[edit]

- The Naked Storm (1952, as Simon Eisner)

- Valerie (1953, as Jordan Park), a novel about a girl accused of witchcraft

- Half (1953, as Jordan Park), a novel about an intersex person

- A Town Is Drowning (1955, with Frederik Pohl)

- Presidential Year (1956, with Frederik Pohl)

- Sorority House (1956, with Frederik Pohl, as Jordan Park), a lesbian pulp novel

- A Man of Cold Rages (1958, as Jordan Park), a novel about an ex-dictator

Uncollected short stories

[edit]

- "Stepsons of Mars", (1940) [as "Ivar Towers" (with Richard Wilson)

- "Callistan Tomb", (1941) [as "Paul Dennis Lavond" (with Frederik Pohl)]

- "The Psychological Regulator", (1941) [as "Arthur Cooke" (with Elsie Balter {later Elsie Wollheim}, Robert A. W. Lowndes, John Michel, Donald A. Wollheim)

- "The Martians Are Coming", (1941) [as "Robert A W Lowndes" (with Robert A. W. Lowndes)]

- "Exiles of New Planet", (1941) [as "Paul Dennis Lavond" (with Frederik Pohl, Robert A. W. Lowndes, Dirk Wylie)]

- "The Castle on the Outerplanet", (1941) [as "S D Gottesman" (with Frederik Pohl, Robert A. W. Lowndes)]

- "A Prince of Pluto", (1941) [as "S D Gottesman" (with Frederik Pohl)]

- "Einstein's Planetoid", (1941) [as "Paul Dennis Lavond" (with Frederik Pohl, Robert A. W. Lowndes, Dirk Wylie)]

- "An Old Neptunian Custom", (1942) [as "Scott Mariner" (with Frederik Pohl)]

- "A Funny Article on the Convention", (1939)

- "New Directions", (1941) [as "Walter C. Davies"]

- "The Failure of the Science Fiction Novel as Social Criticism", in The Science Fiction Novel: Imagination and Social Criticism, ed. Basil Davenport, Advent Press, 1959. (pages 64–101). Brian Stableford called this "an important early piece of sf criticism, sharply pointing out the genre's shortcomings."[2]

Kornbluth's name is mentioned in Lemony Snicket's Series of Unfortunate Events as a member of V.F.D., a secret organization dedicated to the promotion of literacy, classical learning, and crime prevention.

- ^ Rich, p. 16 et passim.

- ^ a b Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1995). "Kornbluth, C.M.". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Griffin. p. 677. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- ^ Rich, Mark (2009). C. M. Kornbluth. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7864-4393-2.

- ^ "Cyril Kornbluth's Postwar Dystopias". Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c Charles Platt, "C. M. Kornbluth: A Study Of His Work and Interview With His Widow", Foundation 17, September 1979, pp.57-63

- ^ Rich, Mark (2009). C. M. Kornbluth. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 127–8. ISBN 978-0-7864-4393-2.

- ^ Webster, Bud. Cyril With an M (or, I'm As Kornbluth as Kansas in August) Archived February 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Baen's Universe, February 5, 2009

- ^ a b c "Obituary at StrangeHorizons.com, 2005". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Rich, Mark (2002). "The Best of C. M. Kornbluth". In Fiona Kelleghan (ed.). Classics of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, Volume 1: Aegypt—Make Room! Make Room!. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. pp. 45–47. ISBN 1-58765-051-7.

- ^ Rich, Mark (2009). C. M. Kornbluth. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 222–223. According to Kornbluth's friend Blish, "The belated appearance of this antique collaboration so upset C.M. Kornbluth...that he wrote a story explaining that the hapless Corwin had been confined in a mental hospital under LSD-25 since around 1950. The story also contains an attack on the agent who sold the collaboration without Kornbluth's permission."

- ^ Coats, Daryl R (2002). "The Space Merchants and The Merchants' War". In Fiona Kelleghan (ed.). Classics of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, Volume 2: The Man in the High Castle—Zothique. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. pp. 485–488. ISBN 1-58765-052-5. The Space Merchants remains the best-known of his satirical works, and its influence can be seen in a number of subsequent works forecasting futures in which a particular group or institution dominates society.

- ^ See for instance: Zoran Živković, Contemporaries of the Future – Savremenici budućnosti, Belgrade, Serbia, 1983, pp. 250–261.

- ^ Rich, Mark, C. M. Kornbluth: The Life and Works of a Science Fiction Visionary (McFarland & Co., 2010) p. 337

- ^ "The Hugo Award (By Year)". www.worldcon.org. Archived from the original on July 31, 2008.

- ^ "Galaxy Bookshelf", Galaxy Science Fiction, August 1977, p. 143.

- Asimov, Isaac. In Memory Yet Green (Doubleday, 1979) and I. Asimov: A Memoir (Doubleday, 1994)

- Knight, Damon. The Futurians (John Day, 1977)

- Pohl, Frederik. The Way the Future Was: A Memoir (Ballantine Books, 1978) ISBN 978-0-345-27714-5

- Rich, Mark. C. M. Kornbluth: The Life and Works of a Science Fiction Visionary (McFarland, 2009) ISBN 978-0-7864-4393-2

- Works by C. M. Kornbluth at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Cyril M. Kornbluth at the Internet Archive

- Works by Cyril M. Kornbluth at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by Cyril M. Kornbluth at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Pohl, Frederik (April 20, 2009). "Cyril". The Way the Future Blogs. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- C. M. Kornbluth at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Past Masters – Cyril with an M, or I'm As Kornbluth as Kansas In August by Bud Webster at Galactic Central