Demographics of Sarawak (original) (raw)

Historical population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 976,269 | — |

| 1980 | 1,235,553 | +26.6% |

| 1991 | 1,642,771 | +33.0% |

| 2000 | 2,009,893 | +22.3% |

| 2010 | 2,399,839 | +19.4% |

| 2021 | 2,470,000 | +2.9% |

| Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia (2021) |

**Sarawak'**s population is very diverse, comprising many races and ethnic groups. Sarawak has more than 40 sub-ethnic groups, each with its own distinct language, culture and lifestyle. This makes Sarawak demography very distinct and unique compared to its Peninsular counterpart. However, it largely mirrors to other territories in Borneo – Sabah, Brunei and Kalimantan.

Ethnic groups of Sarawak

[edit]

Ethnic groups in Sarawak[1]

Other Bumiputeras (mainly Orang Ulu) (6.3%)

Non-Malaysians (4.7%)

Others (0.6%)

A Modern Iban Longhouse, built using new materials and preserving essential features of communal living

Iban girls dressed in full Iban (women) attire during Gawai festivals in Debak, Betong region, Sarawak

In general, there are several major ethnic groups in Sarawak: Iban, Chinese, Malay, Bidayuh, Orang Ulu, Melanau and several minor ethnic groups placed collectively under 'Others', such as Indian, Eurasian, Kedayan, Javanese, Bugis, Murut and many more.

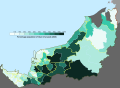

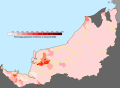

Below are distribution of ethnic groups in Sarawak by state constituencies, based on 2020 census.[2]

The Dayak of Sarawak comprises the Iban and Bidayuh.

Sea Dayaks (Iban) women from Rejang, Sarawak, wearing rattan corsets decorated with brass rings and filigree adornments. The family adds to the corset dress as the girl ages and based on her family's wealth.

The Ibans comprise the largest percentage (28.8%) of Sarawak's population. Iban is native to Borneo and their ancestral homeland is located in the Upper Kapuas, West Kalimantan before their migrations to Sarawak from the 1750s.[3] Formerly reputed to be the most formidable headhunters on the island of Borneo, the Ibans of today are a generous, hospitable and placid people.[4]

Because of their history as farmers, pirates and fishermen, Ibans were conventionally referred to as the "Sea Dayaks". The early Iban settlers migrated from Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo south of Sarawak, via the Kapuas River. They crossed over the Kelingkang range and set up home in the river valleys of Batang Ai, the Skrang River, Saribas, and the Rajang River. The Ibans dwell in longhouses, stilted structures with a large number of rooms housing a whole community of families.[4]

An Iban longhouse may still display head trophies or antu pala. These suspended heads mark tribal victories and were a source of honour. The Dayak Iban ceased practising headhunting in the 1930s.[4]

The Ibans are renowned for their Pua Kumbu (traditional Iban weavings), silver craft, wooden carvings and bead work. Iban tattoos, which were originally symbols of bravery among Iban warriors, have become amongst the most distinctive in the world.[4] The Ibans are also famous for a sweet rice wine called tuak, which is served during big celebrations and festive occasions.[5]

The large majority of Ibans practise Christianity. However, like most other ethnic groups in Sarawak, they still observe many of their traditional rituals and beliefs. Sarawak Iban celebrates colourful festivals such as the generic all-encomposing Gawai Dayak (harvest festival) which is a recent invention and thus held by all Dayak tribes including Iban, Bidayuh and Orang Ulu regardless of their religion. The major festivals of the Iban people are Gawai Bumai (Rice Farming Festival) that includes at least four stages i.e. Gawai Batu (Whetstone Festival), Gawai Benih (Seed Festival), Gawai Ngemali Umai / Jagok (Farm-Healing Festival), Gawai Matah (Harvest-Starting Festival) and Gawai Basimpan (Paddy Safekeeping Festival), Gawai Tuah (Fortune Festival) that comprises Gawai Namaka Tuah (Fortune-Welcoming Festival), Gawai Tajau (Jar Festival) and Gawai Pangkong Tiang (House Post Banging Festival), Gawai Sakit (Healing Festival) including Pelian by a manang shaman, Renong Sakit and Sugi Sakit by a lemambang bard, Gawai Antu (festival of the dead) to honour ancestors and the rarely celebrated but the most elaborate and complex Gawai Burong (Bird Festival) with nine ascending stages in the Saribas/Skrang region or Gawai Amat (Real Festival) in the Baleh region with eight degrees as listed by Masing.

Due to the natural culture of bajalai (sojurn) among Ibans mainly in search of jobs, there is a thriving Iban population of between 300,000 and 350,000 in Johor, found mostly in the area between Pasir Gudang and Masai on the eastern end of the Johor Bahru metropolitan area. Sizeable Iban communities are also present in Kuala Lumpur and Penang, likewise seeking employment. Most will return home during the Gawai Dayak.

Concentrated mainly on the west end of Borneo, the Bidayuhs make up 8% of the population in Sarawak are now most numerous in the hill counties of Lundu, Bau, Penrissen, Padawan, Siburan and Serian, within an hour's drive from Kuching.

Historically, as other tribes were migrating into Sarawak and forming settlements including a degree of historical Malayisation mainly taken place in the coastal areas, the Bidayuhs retreated further inland, hence earning them the name of "Land Dayaks" or "land owners". The word Bidayuh in itself literally means "land people" in Biatah dialect. In Bau-Jagoi/Singai dialect, the pronunciation is "Bidoyoh" which also carry the same meaning.

The traditional community construction of the Bidayuh is the "baruk", a roundhouse that rises about 1.5 metres off the ground. It serves as the granary and the meeting house for the settlement's community. Longhouses were typical in the olden days, similar to that of the Ibans.

Typical of the Sarawak indigenous groups, the Bidayuhs are well known for their hospitality, and are reputed to be the best makers of tuak, or rice wine. Bidayuhs also use distilling methods to make arak tonok, a kind of moonshine.[6]

The Bidayuhs speak a number of different but related dialects. Some Bidayuhs speak either Iban or Sarawak Malay as their main language. While some of them still practise traditional religions, the majority of modern-day Bidayuhs have adopted the Christian faith with a few villages embracing the Islamic faith as a minority group within the Bidayuh community.

This ethnic group forms a small minority with very little or no comprehensive studies done by any party on their dialect, culture/customs and history. Although classified as Bidayuh by the Malaysian government for political convenience, the Salako and Lara culture have nothing in common with the other Bidayuh groups and their oral tradition claim different descent and migration histories. It is understandable that since this group is living within Bidayuh-majority areas and the fact that they also prefer to stay in one permanent inland area, most probably for agricultural reasons instead of branching out to other locations as opposed to the other races, they are grouped together as Land Dayaks.

This tribal community is believed to have originated from Gajing Mountain, at the source of Salakau River, near Singkawang in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Their language is completely different and not intelligible with the other spoken Bidayuh dialects in the other districts. They are mainly found concentrated in the Lundu area. In August 2001, the Salako and Lara community set up the Salako-Lara Association to safe guard and preserve their culture and custom for the future generations.

Orang Ulu is an ethnic group in Sarawak. The various Orang Ulu groups together make up to 6.3% of Sarawak's population. The phrase Orang Ulu means upriver people and is a term used to collectively describe the numerous tribes that live upriver in Sarawak's vast interior. Such groups include the major Kayan and Kenyah tribes, and the smaller neighbouring groups of the Kajang, Kejaman, Punan, Ukit, and Penan. Nowadays, the definition also includes the down-river tribes of the Lun Bawang, Lun Dayeh, "mean upriver" or "far upstream", Berawan, Saban as well as the plateau-dwelling Kelabits. Orang Ulu is a term coined officially by the government to identify several ethnics and sub-ethnics who live mostly at the upriver and uphill areas of Sarawak. Most of them live in the district of Baram, Miri, Belaga, Limbang and Lawas.

The Orang Ulu are artistic people with longhouses elaborately decorated with murals and woodcarvings.[7] They are also well known for their intricate beadwork and detailed tattoos. The Orang Ulu tribe can also be identified by their unique musical sound made by a sapeh, a stringed instrument similar to a mandolin.

The vast majority of the Orang Ulu tribe are Christians but traditional religions are still practised in some areas.

Some of the major tribes making up the Orang Ulu group include:

There are approximately 43,000 Kayans in Sarawak. The Kayan tribe built their longhouses in the northern interiors of Sarawak midway on the Baram River, the upper Rejang River and the lower Tubau River, and were traditionally headhunters.

They are well known for their boat making skills. The Kayan people carve from a single block of belian, the strongest of the tropical hardwoods.[8]

Although many Kayan have become Christians, some still practise paganistic beliefs, but this is becoming more rare.[9]

The Lun Bawang are indigenous to the highlands of East Kalimantan, Brunei (Temburong District), southwest of Sabah (Interior Division) and northern region of Sarawak (Limbang Division). Lun Bawang people are traditionally agriculturalists and rear poultry, pigs and buffalo.

Lun Bawangs are also known to be hunters and fishermen. Alternatively, they are also collectively called the Murut of Sarawak and are closely related to the Lun Dayeh of Sabah, Kalimantan and Murut Brunei.[10]

With a population of approximately 6000, the Kelabit are inhabitants of Bario – a remote plateau in the Sarawak Highlands, slightly over 1,200 meters above sea level. The Kelabits form a tight-knit agrarian community and practicing unique agricultural practices for generations. Famous for their rice-farming, they also cultivate a variety of other crops which are suited to the cooler climate of the Highlands of Bario. The Kelabits are closely related to the Lun Bawang.

The Kelabit are predominantly Christian, the Bario Highlands having been visited by Christian missionaries many years ago. A Christian revival, the Bario revival changed them.[11]

With the population about 64,000, the Kenyah inhabit the Upper Belaga and upper Baram. There is little historical evidence regarding the exact origin of the Kenyah tribe. Their heartland however, is Long San, along the Baram River and Belaga along Rajang River. Their culture is very similar to that of the Kayan tribe with whom they live in close association.

The typical Kenyah village consists of only one longhouse. Most inhabitants are farmers, planting rice in burnt jungle clearings. With the rapid economic development, especially in timber industry, many of them work in timber camps.[_citation needed_]

The Penan are the only true nomadic people in Sarawak and are amongst the last of the world's hunter-gatherers.[1] The Penan make their home under the rainforest canopy, deep within the vast expanse of Sarawak's jungles. Even today, the Penan continue to roam the rainforest hunting wild boar and deer with blowpipes.[_citation needed_]

The Penan are skilled weavers and make high-quality rattan baskets and mats. The traditional Penan religion worships a supreme god called Bungan. However, the increasing number who have abandoned the nomadic lifestyle for settlement in longhouses have converted to Christianity.[12]

Not to be confused with the Penan, the Punan Bah or Punan is a distinct ethnic group found in Sarawak, Malaysia. They are mostly found around the Bintulu area and also in Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo. They live on a mixed economy, engaging in swidden style of agriculture, with hill paddy as the main crop & supplemented by a range of other tropical plants. Hunting, fishing, and gathering of forest resources are the other important contributors to their economy. In recent times, many of the educated younger generation gradually migrated to urban areas such as Bintulu, Sibu, Kuching and Kuala Lumpur in search of better living & returning home occasionally, especially during major festivities such as Harvest Festival / or Bungan festival.

At the moment, the term Punan is often indiscriminately & collectively used to refer to the then unknown or yet to be classified tribes as such as Punan Busang, Penihing, Sajau Hovongan, Uheng Kareho, Merah, Aput, Tubu, Bukat, Ukit, Habongkot and Penyawung. There has been no effort to comprehensively study or research on this ensemble of tribes; these communities lack the privilege and are deprived of their rights to be recognised as individual & unique races (with their own tradition, language & cultural heritage) within the nation's list of ethnic classification, resulting to more than 20 different tribes / ethnics (unrelated to one another) found on the island of Borneo being lumped together into one ethnic group, which includes;

- Punan Busang

- Punan Penihing

- Punan Batu

- Punan Sajau

- Punan Hovongan of Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan

- Punan Uheng Kereho of Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan

- Punan Murung of Murung Raya, Central Kalimantan

- Punan Aoheng (Suku Dayak Pnihing) of East Kalimantan

- Punan Merah (Siau)

- Punan Aput

- Punan Merap

- Punan Tubu

- Punan Ukit/Bukitan

- Dayak Bukat

- Punan Habongkot

- Punan Panyawung

The Sebop is one of the least known groups in Sarawak and they can be found in upper Tinjar river in the Miri Division of Sarawak. Within the Sebup group are the sub-groups that include Long Pekun, Maleng, Lirong, Long Kapah, Long Lubang, Teballau and Long Suku. Cultural researchers acknowledged that there is a Sebop stream in the Usun Apau from which the Sebop got their ethnic name. The Sebup ancestors were said to have lived in the adjacent valleys on the southern side of Usun Apau namely; Seping, Menapun, Menawan and Luar rivers before they moved north towards the Tinjar. Today the Sebup are found in Long Luyang, Long Batan, Long Selapun, Long Pala, Long Nuwah and Long Subeng. Amongst the longhouses, Long Luyang is the longest and most populated Sebop settlement. It comprises more than 100 units.

The Sebop are Christians and their cultural festival is Pesta Coen, a celebration that was used to mark the successful returned of their warriors (Lakin Ayau) from the battlefield. Today it is celebrated as a social cultural festival for everyone to return to the longhouse. Among the highlights of the celebration are the raising up of the gigantic ceremonial pole (Kelebong) as well as the traditional dances and songs.

Also known as "Murut Sabah", "Tagal" or "hill people", this indigenous subgroup of the Murut people can be found inhabiting the lowland areas around Lawas & Limbang. They are part of an interstate ethnic group that is found highly concentrated along the borderlands and inland areas of Sabah, Brunei, Kalimantan and Sarawak, with the majority in the former.

The Tagal are mostly shifting cultivators, with some hunting and riverine fishing on the side. They use the Tagol Murut language as the lingua franca of the whole group. It belongs to the North Bornean subdivision of the Austronesian language family. A majority of the Tagal people are Christians, with a few Muslims.

The Bisaya are an indigenous people, concentrated around the Limbang river in northern Sarawak state. Most Sarawakian Bisaya are Christians. The Bisaya are also found in Sabah (around Kuala Penyu and Beaufort). In Sabah, the majority of them are Muslims; the minority practice Christianity. Some of them still practice Paganism. They are believed to be distantly related to the Visayan of the Philippines. Legend belief is such that in the distant past, there were large migration of Bisaya to The Philippines. However the Bisaya dialect is more related to Malay language than the Philippines Visaya language. Such similarities may be due to the standardising effect and influence of the Malay Language has over the Borneon Bisaya as well as all other ethnic languages spoken in Malaysia.

Bisaya’s indigenous people have settled in Borneo for a long time. They are skilled in agriculture such as paddy planting and cultivation of gingers. They also hunt wild animals and rear domestic animals such as chicken, goat and buffaloes. Bisaya people are also skilled in catching fish, both in the rivers and sea.

A replica of a traditional Melanau House

The Melanaus have been thought to be amongst the original settlers of Sarawak.[13] They make up 4.9% of the population in Sarawak.

Originally from Mukah (the 10th Administrative Division as launched in March 2002), the Melanaus traditionally lived in tall houses. Nowadays, they have adopted a Malay lifestyle, living in kampong-type settlements. Traditionally, Melanaus were fishermen and still today, they are reputed as some of the finest boat-builders and craftsmen.[14]

While the Melanaus are ethnically different from the Malays, their lifestyles and practices are quite similar. This is especially the case in the larger towns and cities where most Melanau have adopted the Islamic faith.[15]

The Melanaus were believed to originally summon spirits in a practice verging on paganism. Today most of the Melanaus are Muslims whilst some were converted to Christianity (especially around Mukah & Dalat areas). However some still celebrate traditional animist festivals such as the annual Kaul festival in Mukah District.

Traditional Sarawakian Malay home

The Malays make up 22.9% of the population in Sarawak. Sarawak was a home for several former native Malay kingdoms, including the Sarawak Sultanate (1598–1641), Banting (16th century), Saribas (15th century), Samarahan (13th century) and Santubong (7th century).

Similar to the ethnogenesis development in many parts of Borneo, a large number of the Malays in Sarawak are indigenous to the land and were historically descendant from various native Bornean tribes that have adopted the Malay culture, language and the Islamic faith for centuries, drawn in a process known as Malayisation (Masuk Melayu).[16][17] At the same time, there are also other Sarawakian Malays that can traced their lineage from a diverse origin and ancestries, including Brunei, Sumatera, Natuna, Malay Peninsula, Kalimantan and other regions.

Traditionally fishermen, these seafaring people chose to form settlements on the banks of the many rivers of Sarawak, while others (the native tribes) were absorbed into the Malay identity since most of the historical contacts, religious conversion and assimilation were predominantly taken place in the rivers and coastal areas. Today, many Malays have migrated to the cities where they are heavily involved in the public and private sectors and taken up various professions.

Malay villages, known as Kampungs, are a cluster of wooden houses on stilts, many of which are still located by rivers on the outskirts of major towns and cities, play home to traditional cottage industries. The Malays are famed for their wood carvings, silver and brass craftings as well as traditional Malay textile weaving with silver and gold thread (kain songket). Malay in Sarawak have a distinct dialect which is called Sarawak Malay. It has many elements of the west borneo malay language spoken before contact with the Bruneian sultanate. The culture of Sarawakian Malay is also somewhat unusual such as bermukun, Sarawak zapin, and keringkam weaving. It is possible, though insufficient studies exist, that these are remnants of the Sambas sultanate’s culture, prior to a change in identity and the speaking of a unique hybrid of Malay-Sambas by the previously Sambas speaking natives.

In Federal Constitution, Malays are Muslim by religion, having been converted to the faith some 600 years ago with the Islamification of the native region. Their religion is reflected in their culture and art and Islamic symbolism is evident in local architecture – from homes to government buildings. In Malaysia, people of Indonesian descent: Javanese, Bugis, and Banjar are constitutionally classified as Malays, and have the same rights should they become a citizen.

The Kedayan are an ethnic group residing in parts of Sarawak. They are also known as Kadayan, Kadaian or simply badly spelled as Kadyan by the British. The Kedayan language is spoken by more than 35,000 people in Sarawak, with most of the members of the Kedayan community residing in Lawas, Limbang, Miri and Sibuti areas. A sizable community also exists in Brunei Darussalam and Sabah.

The Kedayans is believed to have Javanese origins. The British Resident Malcolm McArthur attests to their Javanese origins in his Report on Brunei 1904.[18] Meanwhile, historians such as Pehin Jamil claimed the Kedayans were bought over from Java to Borneo by Sultan Bolkiah the 5th during his famous conquests of Borneo.[19] This was due to the Kedayan's prowess in padi farming and other agricultural abilities. Other researchers consider them indigenous to Borneo, having accepted Islam and influenced by Malay culture, primarily by Bruneians.

Kedayan are mainly padi farmers or fishermen. They have a reputation for knowledge of medicinal plants, which they grow to treat a wide range of ailments or to make tonics. The Kedayan tend to settle inland in a cluster pattern, with houses built in the centre and with fields radiating outwards. The Kedayans traditionally tended to be a rather closed community, discouraging contact with outsiders. Intermarriage among relatives was encouraged for economic and social reasons.

The present generation are descended from the original ethnic Javanese people, the majority from the province of Central Java, who arrived in Sarawak as "kuli kontrak", indentured servants who were brought in by the Dutch via Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) during the late 1800s to the 1940s & transferred to a British company to work in the rubber plantations. After the end of their contracts, some of them had decided to settle down & work on land no longer producing rubber. Over the years, these labourers were prosperous & were later given the right of ownership to several hectares of land.

An estimated 5,000 Javanese people are found all over the state, establishing their own villages, with the majority concentrated in Kuching & its surrounding areas. Some of the younger generation still carry traditional Javanese names & are identified as ethnic Javanese in their birth certificates. They are proud of their heritage; the current population still speak the language of their parents & retaining their age-old traditions & practices of their forefathers.

The friendly Javanese are traditionally Muslims, so they have a strong affinity with the Malays, with many of them intermarrying & living within Malay-majority areas & also other communities. They use Sarawak Malay or English as a common lingua franca to communicate with the other ethnic groups.

The Bugis are an ethnic group which had originated from the southwestern province of Sulawesi, Indonesia. They are renowned around the archipelago as adventurous seafarers and merchants, establishing trading routes with other ports along Sarawak's coastal areas over the past few centuries, eventually settling down with their families or taking up local spouses. The Bugis artisans are noted for their expertise in building tongkangs & proas, plying their skills at the fishing villages and local dockyards. They are also skilled farmers, construction workers, traders and fishermen.

The Bugis population in Sarawak is scattered throughout the state. Many can be found living along the coast alongside or within other communities and also opening up small agricultural settlements further inland, especially in the Sarikei district. They are predominantly Muslims and many have amalgamated with the local Muslim society through marriage.

The Indians and generally South Asians in Sarawak are a small geographical and ethno-cultural community, estimated to be between 6,500 people (figure also includes those of mixed parentage and professionals, students and residents from other parts of Malaysia), found mainly in the urban exteriors of Kuching and Miri division. The majority of Indians in Sarawak are Tamils. There are also other Indians minorities from the Punjabi Sikhs, Telugus, Sindhis and Keralites ethnic groups.

The Sikhs were among the earliest South Asians to set foot on Sarawak's soil, recruited by the first White Rajah, Sir James Brooke in Singapore as police officers to bring peace, law and order during the 1857 Chinese uprising in Bau. At a much later stage, the Sikhs were employed as security personnel for the Sarawak Shell Company in Miri and also as government-appointed prison wardens. It is also believed that there were a few Sikhs in the Sarawak Rangers, which was formed in 1872.

As for the Tamils and other minority Indian ethnic groups, their history in the state began during the 1860s, when they were brought in from South India by the second White Rajah Charles Brooke to work in the tea and coffee plantations at Matang Hills. They were also traders and travelers visiting the state for religious, educational or business opportunities. After many years, the South Asian community had extended to include newer immigrants from Sri Lanka, Pakistan and other areas in India. The Indian Muslims were prominent in the restaurant business, textile trade & Indian food production. They were also instrumentally significant in their contribution to the Islamic fellowship and religious welfare in the state with their Muslim Malay brethren.

Many of the present-day Sarawak South Asians are from mixed marriages with the Malays, Chinese & other Sarawak native ethnic groups, with many of the younger generation using English, Sarawak Malay or one of the native or Chinese dialects to communicate with everybody else. They have assimilated well within the state's general population as a culturally distinct group in Sarawak that is rather unique as opposed to the Indian diaspora of Peninsular Malaysia and the Asian region in general. A number of Sarawak Indians can be found working as doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers and other professional careers in the government and private sectors.

Mixed marriages/unions between Europeans and local spouses have been going on for centuries, since the time European traders, sailors and colonists first set foot on Sarawak's soils.

The Eurasians in Sarawak continues to be the smallest of minorities, with many of them rather identifying themselves with the major racial denomination of their local parent rather than that of their European, Australian or American parent, as the local state government does not formally classify them as an official ethnicity. At the moment, the exact number of people in the local Eurasian community is not known, as many of them registered themselves (for administrative and social ease) as Iban, Bidayuh, Chinese, Malay, Melanau, Orang Ulu, Indian or simply under "others". Besides assimilating themselves into the general populace, many of them had also migrated to Peninsular Malaysia or their foreign parents' countries of origin.

The local Eurasians established the Sarawak Eurasian Association (SEA) in the year 2000 to foster closer ties among members of this community and also to raise awareness on the existence of this distinct group. Their association is quite unique, if compared to the Eurasian associations of Peninsular Malaysia, as it is composed by members of different religious faiths.

A Paifang in Malaysia-China Friendship Park, Kuching

Chinese records has shown that China had a trading contact with Borneo as early as 600 A.D. when a country known as "Po Ni" (present day Brunei) sent tribute to Tang Emperor. When British explorer James Brooke arrived in Borneo in 1839, there were several hundred Chinese working in pepper plantations there. The first Hakka migrants worked as labourers in the gold mines at Bau. This was followed by the migration of Fuzhou people to the Rajang basin in 1900s, working as farmers in cash crop industries such as pepper, rubber, sago, and oil palm. Meanwhile, Hokkien people from the Xiamen area, worked as merchants. Lastly, the Cantonese people, who made up majority of the sinitic people population in the Peninsular Malaysia, not been really attracted to Sarawak.[20]

As of 1989, 30% of Sarawak Chinese population was made up of ethnic Hakka, followed by Fuzhounese (30%), Hokkien (12%), and Cantonese (8%). The Sinitic people made up 73% of the population in Kuching and 77% in Sibu.[20]

Through their clan associations, business acumen and work ethic, the Sinitic people organised themselves economically and rapidly dominated commerce. Today, the Sinitic people are amongst Sarawak's most prosperous ethnic groups.

Today, they make up 17.1% of the population of Sarawak (as reported by Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) in 2021), and consist of communities built from the economic migrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Sarawak Sinitic people belong to a wide range of ethnic groups, the most significant being:

Whereas Hakka is spoken predominantly by the farmers in the interior, Hokkien and Teochew are the dominant languages spoken within the major trading towns and among early traders and businessmen. Hainanese (a.k.a. Hailam) were well known as coffee-shop operators, the Henghua are famous as fishermen. The notable difference between the Sarawakian Sinitic people and those presiding in West Malaysia is the latter’s common use of Cantonese. Malaysian Mandarin, however, has become the unifying language spoken by all the distinct ethnic groups with Sinitic origins in both East and West Malaysia, replicating China. The Hakka people in Kuching, Sarawak came from Jieyang, Guangdong. The Hokkien came from Zhao'an, Fujian. The Teochew came from Shantou and Chaozhou in Guangdong, the Shanghainese came from Shanghai, Hainanese from Hainan, Cantonese from Guangdong, Fuzhounese from Fuzhou, Fujian. The Kwongsai people came from Guangxi, Minnanese people came from Xiamen, Lastly the Henghuas or Hinghwa or Puxian people from Putian, Fujian.

The Sinitic people maintain their ethnic heritage and culture and celebrate all the major cultural festivals, most notably Lunar New Year, the Hungry Ghost Festival and Christmas. The Sarawak Sinitic people are predominantly Buddhists and Christians.

Religions of Sarawak

[edit]

Christianity is the largest religion in Sarawak, representing 50.1% of the total population according to the 2020 census.[21] Sarawakians practice a variety of religions, including Christianity, Chinese folk religion (a fusion of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and ancestor worship), Islam, Baha’i Faith and animism.[22] Unsurprisingly, the issue of Islam as state religion divides the Muslim and non-Muslims with a contrasting 85% supporting and opposing, respectively. Nevertheless, 93% of Sarawakians consider their regional Sarawak identity to be their first choice in defining themselves which is in stark contrast to Peninsular Malaysia where 55% see religion as their most important identity marker. This is in line with the Malaccan Sultanate from which the Malay language and culture stems.[23] Adopting a common name, language and religion has united the various West Malaysian indigenous communities and many Sambas indigenous people of Kuching. Sarawakians across all religions express majority support for increased autonomy for the state - at 76% overall.[24]

St. Joseph's Cathedral, Kuching, a Roman Catholic cathedral in Kuching, Sarawak.

Christianity makes up the largest religion in Sarawak. Sarawak is the state with the highest percentage of Christians in Malaysia and the only state with a Christian majority. According to the 2020 census, Christians make up 50.1% of the population of Sarawak.[21]

Protestants, mostly Anglicans, make up the majority, followed by more than 441,300 Catholics.[25] Other Christian denominations in Sarawak include Methodists, Borneo Evangelical Church (or Sidang Injil Borneo, S.I.B.) and Baptists. Many Sarawakian Christians are mostly non-Malay Bumiputera, ranging from Iban, Bidayuh, Orang Ulu, Murut and Melanau.

Denomination of Christians in Sarawak may vary according to their race, although this is not necessarily true. For example, most Chinese Christians are Methodists, most Ibans and Bidayuhs are either Roman Catholics or Anglicans, whilst most Orang Ulu are S.I.B.s. Church plays an important part in shaping morality of the communities, while many Christians view the church as a religious place. Professing Christianity has led to the abolition of some previous rituals by indigenous ethnics such as headhunting and improper disposal of dead bodies. Since the majority of people indigenous to Sarawak are Christians, these people have adopted Christian names in English or Italian, such as Valentino, Joseph, and Constantine. Almost 93% of the Iban, Kelabit, and Bidayuh have changed their traditional names to English names since they converted to Christianity. Many young indigenous Iban, Kelabit, and Bidayuh people in Sarawak will not practice the ceremonies of their ancestors such as Miring, the worship of Singalang Burung (local deity), and celebration of Gawai Antu. The Bidayuhs are mainly Pagans or animists before they convert to Christianity and they believe in ancestral worship and in the ancient spirits of nature. Due to this, they have big celebrations like the Gawai (1 June), which is a celebration to please the padi spirit for a good harvest and nowadays, since 60% of the population has converted to Christianity, the young Bidayuh generation will celebrate only Christmas as their first priority. Christians among indigenous ethnics have also embraced many Christian values such as preserving modesty and dedication to God.[14]

Christianity has also contributed to the betterment of the education system in Sarawak. There were a lot of missionary schools built during the 1950s to early 1980s.[26] Christianity has gained popularity throughout Sarawak, transcending race and religion. Due to federalisation of the education system, most of these missionary schools have been converted into government national schools. Participation of the church in these schools has been reduced. The Malaysian government has allowed the schools to continue using religious symbols on school buildings and teaching Christian values to non-Muslim students.[27]

Christians in Sarawak observe many Christian festivals just like their counterparts in other part of the world, namely Christmas Day, Good Friday, Easter Monday, All Soul's Day, and Ascension Day. However, only Christmas and Good Friday are public holidays in Sarawak.[28]

Kuching Mosque

Islam is the second-largest religion in Sarawak, after Christianity. According to the 2020 census, 34.2% of Sarawak's population were Muslim.[21] All Malay-speaking Muslims are designated Malays by the Malaysian Constitution.[29] Malay Muslim culture contributes significantly to Sarawakian Muslim tradition as a whole especially for weddings, circumcision (coming of age ritual), 'majlis doa selamat', etc. Sarawak Malays were originally a mixture of Malay migrants from the rest of Southeast Asian archipelago that migrated to the area hundreds of years ago. They intermarried with local ethnic groups such as Pegu, Bliun and Seru, these ethnic groups were later absorbed into ethnic Sarawak Malay identity.[30]

Other ethnic groups such as Melanaus and Miriek have retained their languages in whole and have strong Islamic influence in their traditions from their ancestors. Sarawak was once home to various Islamic-Malay kingdoms such as Saribas, Melano, Santubong and Kalaka, etc.[31] They have also absorbed traditions from the Malaccan sultanate.[32] Melanaus, depending on which region or kampung they live in, are normally either Muslim or Christian (while a small number are pagans). Most of them live in Kuching, Matu, Mukah, Igan and Bintulu. About 65% of Melanau people are of the Sunni Muslim belief while the remaining 35% are either Christians or animists.[33]

Kedayan is another distinct ethnic group from Malay and Melanau, but have been Muslim since the time of the Brunei Sultanate, another ally of the Malaccan Sultanate [34] Although small in number, with the majority of their closest kin living in Brunei, they contribute to a majority of the Muslim population in Sibuti and Bekenu district. Despite being designated as a distinct ethnic group, they speak a dialect of Brunei Malay.

Administratively, Islam is under the authority of the state of Islamic Council, which is Majlis Islam Sarawak (MIS), a state government agency. Under MIS, there are various agencies dealing with various aspects of Islam such as Jabatan Agama Islam Sarawak (JAIS), Majlis Fatwa and Baitulmal Sarawak.[35]

Muslims in Sarawak observe all Islamic festivals, such as Hari Raya Aidilfitri (Puasa), Hari Raya Aidiladha (Haji), Awal Muharram and Maulidur Rasul. All these celebrations have been commenced as public holidays in Sarawak. However, Israk Mikraj, Awal Ramadhan and Nuzul Quran, although observed, are not public holidays.[36]

Tua Pek Kong Temple, Sibu

Buddhism is the traditional religion of the overseas Chinese community in Sarawak, brought by their ancestors before the Cultural Revolution in China. According to the 2020 census, 12.8% of Sarawakians were Buddhist.[21] Many of the Sarawakian Chinese community, which comprises the bulk of the Buddhist population, actually practise a mixture of Buddhism, Taoism and Chinese folk religion. As there is no official name for this particular set of beliefs, many followers instead list down their religion as Buddhism, mainly for bureaucratic convenience. Buddhists from other ethnic especially Bumiputera are rare and almost insignificant to be related with, perhaps in small community with humble and low profile practice of the Buddhist ceremony among some Bumiputra people in Sarawak. Buddhists in Sarawak observe Wesak Day. It is a public holiday in Sarawak.

Unlike their fellow Peninsular Malaysians, Sarawak Hindus are very small in number. Almost all Hindus in Sarawak are Indians, while some are Chinese and other indigenous people through inter-marriages. There are less than 10 Hindu temples throughout Sarawak, most of them are located in Kuching and Miri. Currently there are 5,000 Hindus (representing 0.2% of the population) in Sarawak.

Hindus in Sarawak observe Deepavali and Thaipusam. However, none of these festivals are public holidays in Sarawak.

Gurdwara Sahib in Kuching

The first Gurdwara was built in 1911 in Kuching, built by the Sikh community of pioneers in the state, mainly police and security personnel. At the present, there are four known Gurdwaras in the state, with one each located in Kuching, Miri, Sibu and Bau, with the latter no longer in existence since the late 1950s, due to the fact that there were no longer any Sikhs in that area.

Besides being used as places of worship, the Gurdwaras also hold weekly Gurmukhi classes and also serve as community centres for the thriving Sikh community.

Baháʼí is one of the recognised religions in Sarawak. Various races embraced the Baháʼí Faith, from Chinese to Iban, Bidayuh, Bisayahs, Penans and Indians. In towns, the majority Baháʼí community is often Chinese, but in rural communities, they are of all races, Ibans, Bidayuhs, etc. In some schools, Baháʼí associations or clubs for students exist.

Baháʼí communities are now found in all the various divisions of Sarawak. However, these communities do not accept assistance from government or other organisations for activities which are strictly for Baháʼís. If, however, these services extend to include non-Baháʼís also, e.g. education for children's classes adult literacy, then sometimes the community does accept assistance.

The administration of the Baháʼí Faith is through Local Spiritual Assemblies. There is no priesthood among the Baháʼís. Election is held annually without nomination or electioneering. The Baháʼís should study the community and seek those members who display mature experience, loyalty, are knowledgeable in the Faith.

There are more than 45,000 Baháʼís in more than 230 localities in Sarawak.

Many Dayak especially Iban continue to practice traditional ceremonies, particularly with dual marriage rites and during the important harvest and ancestral festivals such as Gawai Dayak, Gawai Kenyalang and Gawai Antu.

Other ethnicities who have a rapidly dwindling and trace amount of animism practitioners are Melanau and Bidayuh.

- ^ "Taburan Penduduk dan Ciri-ciri asas demografi (Population Distribution and Basic demographic characteristics 2010)" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2015. p. 13 [26/156]

- ^ "TABURAN PENDUDUK MENGIKUT PBT & MUKIM 2010". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ "Iban as a koine language in Sarawak". 1 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Journey Malaysia. Journey Malaysia. Retrieved on 29 August 2021.

- ^ Tourism Malaysia USA Archived 20 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Tourism Malaysia USA. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ LongHuse Archived 5 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Longhouse.org.my (15 October 2009). Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Vtaide. Vtaide. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Heesyam, Faizal. (27 July 2010) Discover Borneo Archived 20 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Discover Borneo. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ XFab Archived 15 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. XFab. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Sri Lankan News Web Archived 24 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Srilankanewsweb.com. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Bulan, Solomon and Bulan-Dorai, L (2014), The Bario Revival, HomeMatters Network

- ^ Discover Borneo Archived 20 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Discover Borneo. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Gomiri Archived 20 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Gomiri. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ a b Museum of Learning. Museumstuff.com. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Melanau | The Grown Ups. Swingrownups.wordpress.com. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ "Some Aspects of Iban-Maloh Contact in West Kalimantan" (PDF). 7 May 2023.

- ^ "Asal usul Melayu Sarawak: Menjejaki titik tak pasti". 1 May 2023.

- ^ McArthur, M. S. H. (1987). Report on Brunei in 1904. Ohio University Center for International Studies.

- ^ Al-Sufri, M. J., & Hassan, M. A. (2000). Tarsilah Brunei: the early history of Brunei up to 1432 AD (Vol. 1). Brunei History Centre, Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports.

- ^ a b Zepp, Raymond (March 1989). "The Chinese in Sarawak". Bulletin de Sinologie. Nouvelle Série (53). French Centre for Research on Contemporary China: 19–21. JSTOR 43436606.

- ^ a b c d e "Census Dashboard". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Tititudorancea. Tititudorancea. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Sneddon, James N. (2003), The Indonesian language: its history and role in modern society, University of New South Wales Press, ISBN 0-86840-598-1, pp. 74–77

- ^ Hock Guan, Lee (April 2018). "The ISEAS Borneo Survey: Autonomy, Identity, Islam and Language/Education in Sarawak" (PDF). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 19: 3–8.

- ^ Ruling coalition holds Malaysia's Christian-majority state, Union of Catholic Asian News, Dec 2021

- ^ Travel Malaysia Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Go2travelmalaysia.com. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Network Base. Networkbase.info. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ One Stop Malaysia Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. One Stop Malaysia. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Tititudorrancea. Tititudorancea.com. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ "Mencari kaum yang hilang di Sarawak". 29 July 2016.

- ^ Al-Sufri, M. J. (1990). Tarsilah Brunei: sejarah awal dan perkembangan Islam (Vol. 1). Jabatan Pusat Sejarah, Kementerian Kebudayaan Belia dan Sukan.

- ^ Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Y. (2015). A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400-1830. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88992-6.

- ^ Borneo Tropicana Archived 17 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Borneo Tropicana. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 2A, The Indian Sub-Continent, South-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim West. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.

- ^ Travel Malaysia Archived 6 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Go2travelmalaysia.com. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Go Malaysia. Go Malaysia. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.