Exclusionary zoning (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Use of zoning ordinances to keep low-income people and people of color out of neighborhoods

For geographic areas where an authority prohibits specific activities, see Exclusion zone.

Exclusionary zoning is the use of zoning ordinances to exclude certain types of land uses from a given community, especially to regulate racial and economic diversity.[1] In the United States, exclusionary zoning ordinances are standard in almost all communities. Exclusionary zoning was introduced in the early 1900s, typically to prevent racial and ethnic minorities from moving into middle- and upper-class neighborhoods. Municipalities use zoning to limit population density, such as by prohibiting multi-family residential dwellings or setting minimum lot size requirements. These ordinances raise costs, making it less likely that lower-income groups will move in. Development fees for variance (land use), a building permit, a certificate of occupancy, a filing (legal) cost, special permits and planned-unit development applications for new housing also raise prices to levels inaccessible for lower income people.[2]

Exclusionary land-use policies exacerbate social segregation by deterring any racial and economic integration, decrease the total housing supply of a region and raise housing prices. As well, regions with much economic segregation channel lower income students into lower performing schools thereby prompting educational achievement differences. A comprehensive survey in 2008 found that over 80% of United States jurisdictions imposed minimum lot size requirements of some kind on their inhabitants.[3] These ordinances continue to reinforce discriminatory housing practices throughout the United States.[4][5]: 52–53

Around the turn of the 20th century, rapid immigration and urbanization in the United States transformed the country. Middle and upper-class citizens encounter greater diversity than they had before and many cities began implementing the first exclusionary zoning policies. In 1908, Los Angeles adopted the first citywide zoning ordinance to protect residential areas from industrial nuisances. However, the noted urban planner Yale Rabin observed, "What began as a means of improving the blighted physical environment in which people lived and worked" became "a mechanism for protecting property values and excluding the undesirables." In 1910, Baltimore enacted the first racial zoning ordinance, and the practice spread quickly.[6] Many early regulations directly barred racial and ethnic minorities from community residence until explicit racial zoning was declared unconstitutional in 1917.[7]: 6&25 Less explicitly ethnic but still exclusionary ordinances continued to gain popularity throughout the country.[5]: 48–49 Despite resistance from excluded peoples and activists, these ordinances are still used extensively across the country.

The increased use of exclusionary zoning finally caused the United States Department of Commerce to address the issue with the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act in 1922. The legislation established the institutional framework for zoning ordinances and delegated land-use power to local authorities for the conservation of community welfare and provided guidelines for appropriate regulation usage.[8] In light of those developments, the Supreme Court considered zoning's constitutionality in the 1926 landmark case of Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co. The Court ultimately condoned zoning as an acceptable means of community regulation. After the decision, the number of municipalities with zoning legislation multiplied, from 368 in 1925 to over 1,000 in 1930.[9]

After the end of World War II and the country's subsequent suburbanization process, exclusionary zoning policies experienced an uptick in complexity, stringency and prevalence as suburbanites attempted to more effectively protect their new communities. Many people fled the cities and their unwanted elements as they searched for their suburban utopia. They feared that left unchecked, the very city elements that they had escaped would follow them into the suburbs. Thus, middle-class and affluent whites, who constituted the majority of suburban inhabitants, more frequently employed measures preventing immigrant and minority integration.[8] As a result of resident's newly-found protectionism, the number of jurisdictions with such ordinances increased to over 5,200 by 1968.[9]

Well-off whites mainly inhabited the suburbs, but the remaining city residents, primarily impoverished minorities, faced substantial obstacles to wealth. Many attributed their impecunious state to their exclusion from the suburbs. In response, a flurry of exclusionary zoning cases were brought before the Supreme Court in the 1970s that would ultimately determine the tactic's fate. The Supreme Court nearly always sided with the proponents of exclusionary zoning, which virtually halted any zoning reform movement. The ability of minorities and other excluded populations to challenge exclusionary zoning became essentially nonexistent and has allowed the policy's unabated continuation.[10]

American courts have historically most greatly valued individual property rights. However, more recently, concern for the general community welfare has begun taking precedence thus exculpating most exclusionary zoning measures.[8] Communities are granted freedom to enact policies in accordance with community welfare goals even in the case that they infringe upon a specific individual's property rights. Courts also have regularly ruled as if municipal regulatory power emanated from their role as agents for local families rather than for the government. Regulation was equated with some manner of 'market force' rather than 'state force' thereby allowing the policies to bypass many questions of justification required for state policy enactment.[11]: 97 For example, they did not have to prove that their policies benefited the well-being of society at large. Rather, they could merely enact regulations on the sole basis that it was their prerogative as an agent of the market regardless of any adverse effects on others. Therefore, exclusionary mechanisms were allowed to endure as complaints about the negative effects on the excluded population ultimately became null and irrelevant.

Buchanan v. Warley 1917: A Louisville city ordinance prohibiting the sale of property in majority-white neighborhoods to black people was brought to court. It was ultimately declared that such racial restriction was unconstitutional and a breach of individuals' freedom of contract.[7]: 6

Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co. 1926: The Ambler Realty company accused the Village of Euclid of depriving their liberty with its ban on industrial uses. The ban on industry reduced the company's land value from 10,000downto10,000 down to 10,000downto2,500 per acre and undermined the company's right to govern its own property.[8] Court officials, however, sided with the village and upheld the ordinance on the basis that it was a just and reasonable delegation of the state's police power. Municipals, the court ruled, are entitled to regulate community property when it reflects the best interests of its constituents. This landmark decision would lay the constitutional foundation for all future exclusionary zoning policies.[11]: 89–91

Belle Terre et al. v. Boras et al. 1974: A group of six unrelated college students living together challenged a neighborhood ordinance that restricted unit residence to no more than two unrelated individuals. The case differed from the Euclid one in that there was no residential land use or structural type at issue. It rather addressed the constitutionality of directly regulating occupancy. Eventually, the court sanctioned this variety of ordinances. A community's pursuit of homogeneity was self-justifying, the court logic went, so long as there is no explicit class or racial discrimination. Their decision hinged on the view that an area's definition of the family is acceptable as long as a rational basis exists for the determination. It is not a judge's domain to overrule such legislative decisions.[11]: 96–97 Implicit within the case's ruling is permission for exclusionary zoning regulations to attempt preservation of identity in the context of family compositions. Thus, given the previous Village of Euclid decision, municipalities were now granted the right to legislate both external property and internal inhabitant characteristics.

Warth v. Seldin 1975: Low-income individuals and a not-for-profit housing organization sued a New York State suburb contending that the community's exclusionary principles increased their housing costs. The court ultimately asserted that any harm is a generalized consequence of real estate economics rather than a specific result of the suburb's regulations. Therefore, since the elevated housing costs could not be directly attributed to a certain exclusionary policy, the court ruled in favor of the suburb's ordinance. Specific legislation would not be held accountable for any overarching effects that it may have advanced. Therefore, exclusionary mechanisms could expand without threat of lawsuits from refused populations.[11]: 71

Restrictions on the supply of housing units

[edit]

Municipalities will often impose density controls on developable land with the intention of limiting the number of individuals that will live in their particular area. This process denies neighborhood access to certain groups by limiting the supply of available housing units. Such concerns may manifest in measures prohibiting multi-family residential dwellings, limiting the number of people per unit of land and mandating lot size requirements. Most vacant land is particularly over-zoned in that it contains excess regulations impeding the construction of smaller, more affordable housing. In the New York City suburbs of Fairfield County, Connecticut, for instance, 89% of land is classified for residential zoning of over one acre.[7]: 10 This type of regulation ensures that housing developments are of adequately low density. Such ordinances can collectively raise costs anywhere from 2 to 250% depending on their extensiveness.[7]: 13–14 With such high costs, lower-income groups are effectively shut out of the community's housing market.

In some places such as Portland, Oregon, being in a historic district can make it difficult to demolish buildings or construct new ones; designation can be sought over owners' wishes to prevent increased housing supply in a neighborhood even if individual structures not historic.[12]

Direct cost increases

[edit]

Another means by which exclusionary zoning and related ordinances contribute to the exclusion certain groups is through direct cost impositions on community residents. In the 1970s, municipalities established measures decreeing developers greater responsibility in the provision and maintenance of many basic neighborhood resources such as schools, parks, and other related services.[7]: 12 Developers incur excess costs for these aforementioned obligations which are then passed on to consumers in the form of fees or a financial bond. For instance, many newer developments charge monthly recreational fees to fund community facilities. Also, restrictive zoning regulations have made the approval process for development more arduous and extensive. The increased bureaucracy and red tape has meant that developers now encounter a myriad of fees for variance (land use), a building permit, a certificate of occupancy, a filing (legal) cost, special permits and planned-unit development applications.[7]: 13 Not only do the fees diminish builder profits, but they also lengthen the development process which further drains company resources. Just as with the community resource requirements, these extra costs are inevitably delivered to housing purchasers. All of these fees accumulate and escalate unit prices to levels inaccessible for lower income people.

The valuation of the unit may experience a decline. According to one paywall study from 2004 by Robert Cervero and Michael Duncan, specific to Santa Clara County, California, increased property values and tax proceeds have resulted from racist and classist exclusionary practices.[13] Surmised from one 1993 paywall study by William Bogart, in order to augment their own monetary assets, upper-class individuals enact regulations prohibiting neighborhood accessibility for specific groups.[14]

Density externalities

[edit]

Exclusionary zoning's assurance of lower densities precludes some potential deleterious consequences associated with increased population density. More people in a community can result in more traffic congestion, which may interfere with the original inhabitants' quality of life. Greater populations may lead to strains on potentially limited or vulnerable environmental resources such as water or air, if the urban form is designed in an automobile-dependent way.[14]

Some suburbanites also champion exclusionary zoning policies on the simple motivation of excluding unalike groups irrespective of any negative effects that they may impose. Some researchers partly attribute the policies to class or racial prejudice as individuals often prefer to live in homogeneous communities of people similar to themselves.[15] Others assert that race is merely a proxy and that upper classes and whites stereotype overall neighborhoods containing certain groups rather than the individual group members specifically. Such areas are stigmatized for their perceived correlation with high crime, low-quality schooling and low property values.[16] Additionally, the entrance of heterogenous residents could have severe political ramifications. If enough lower-income individuals, who typically differ in political ideology, move into the community, then they may garner enough political power to overshadow the traditional contingent. As such, the original constituency is politically subjugated in the very community in which they used to enjoy power.[14] Thus, whites and upper classes divert those groups for their unsuitable characteristics, perceived link with negative neighborhood qualities and threat to community politics.

Racial/economic stratification

[edit]

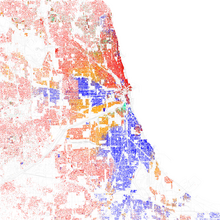

Racial composition of Chicago area (2010 Census)

Exclusionary zoning initiatives reduce the presence of both rental housing and ethnic minorities in an affected community.[17] Despite federal court mandates prohibiting blatant racial and economic discrimination, many of these less fortunate groups have encountered systematic obstacles preventing access to higher-income areas. Studies have demonstrated that higher-income and predominately-white jurisdictions generally adopt more restrictive land-use regulations.[15] As a result, minority and lower-income groups are essentially locked into rigidly segregated neighborhoods. Residential segregation has remained constant from the 1960s to 1990s in spite of civil rights progress, primarily because of hindering policies that relegate certain groups to less-regulated areas.[10]: 47 Accordingly, the prevalence of exclusionary land-use policies exacerbates social segregation by deterring any racial and economic integration.

Restrictive from the standpoint of economic efficiency, regulations that limit density also decrease the total housing supply of a region. With the lowered housing stock, market demand for the units is amplified thus raising prices. Along with reduced overall supply, the insistence on detached single-family homes also increases individual housing costs as homeowners must individually account for many land improvements (such as sidewalks, streets, water and sewer lines) that otherwise could be shared among more inhabitants as in denser communities. Studies in Maryland and the District of Columbia find that higher densities cut per capita water and sewer installation costs by 50% and road installation/maintenance by 67%.[7]: 6 Moreover, residential developers and homeowners must implement expensive housing features to comply with jurisdictional zoning mandates. For instance, setback (land use) requirements that are commonly used throughout the United States increase total unit costs by 6.1 to 7.8%.[18]

All land-use factors contribute to mounting housing unit prices in comparison to less regulated communities. The communities specifically administering restrictive ordinances experience higher housing costs, like neighboring areas. Exclusionary zoning affects the overall regional housing market by reducing the total supply of units. As there are less available units, the demand for the units will rise causing more expensive housing across the area. Ultimately, the additional competition and resulting costs accumulate making regional markets with strictly regulated housing have 17% higher rents and 51% higher housing prices than do leniently governed areas.[19] Therefore, housing regulations evidently have significant impacts on both the specific community and overall region's housing expenditure.

Education has been proven to be vitally important to human welfare, as it can promote higher incomes, greater labor market performance, a higher social status, increased societal participation and improved health.[20]: 2 Along with individual benefits, educational attainment in the United States also has the ability to foster greater regional and national economic prosperity as an educated populace can better adapt to global economic trends and conditions. Nevertheless, there is a stark education inequality between various groups as the average low-income student attends a school that scores on the 42nd percentile on state exams while the average middle and upper-income student attends a school that scores on the 61st percentile on state exams.[20]: 8 The vast differences in attainment cannot be accounted for by assuming inheritable group differences, as empirical research has demonstrated that simple genetic contrasts are insufficient to explain education disparities.[21] Rather, environmental factors involving school quality also contribute to educational achievement.

Regions with much economic segregation, which, as noted earlier, partially stems from exclusionary zoning, also have the largest gaps in test scores between the low-income and other students.[20]: 10 Low-income students are trapped in inadequate schooling since their economic conditions limit access of high-performing schools and education. Across the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the United States, costs of housing is 2.4 times higher for units zoned to higher-performing public schools than to those zoned to lower-performing ones.[20]: 14 Therefore, exclusionary zoning serves to channel lower income students into lower performing schools thereby prompting educational achievement differences.

- Zoning

- Inclusionary zoning

- Urban planning

- Affordable housing

- Residential segregation

- Housing segregation

- Urban decay

- Social exclusion

- Status attainment

- Social stratification

- Gentrification

- ^ "Exclusionary Zoning". Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Understanding Exclusionary Zoning and Its Impact on Concentrated Poverty". 2016-06-23.

- ^ Gyourko, Joseph; Albert Saiz; Anita Summers (2008). "A New Measure of the Local Regulatory Environment for Housing Markets: The Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index". Urban Studies. 45 (3): 701. Bibcode:2008UrbSt..45..693G. doi:10.1177/0042098007087341. S2CID 221013013.

- ^ "Exclusionary Zoning Continues Racial Segregation's Ugly Work". 2017-08-04.

- ^ a b Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: W. W. Norton.

- ^ Silver, Christopher (1997). "The Racial Origins of Zoning in American Cities". In Manning Thomas, June; Ritzdorf, Marsha (eds.). Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. pp. 23–42.

- ^ a b c d e f g Babcock, Richard; Bosselman, Fred (1973). Exclusionary Zoning: Land Use Regulation and Housing in the 1970s. New York: Praeger Publishers.

- ^ a b c d King, Paul (1978). "Exclusionary Zoning and Open Housing: A Brief Judicial History". Geographical Review. 68 (4): 459–469. Bibcode:1978GeoRv..68..459K. doi:10.2307/214217. JSTOR 214217.

- ^ a b United States National Commission on Urban Problems, 1969.

- ^ a b Ritzdorf, Marsha (1997). Locked Out of Paradise: Contemporary Exclusionary Zoning, the Supreme Court, and African Americans, 1970 to the Present. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- ^ a b c d Levine, Jonathan (2006). Zoned Out: Regulation, Markets, and Choices in Transportation and Metropolitan Land-Use. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- ^ "Bogus "Historic" Districts: The New Exclusionary Zoning?". Sightline Institute. 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Cervero, Robert; Michael Duncan (2004). "Neighborhood composition and residential land prices: does exclusion raise or lower values?". Urban Studies. 41 (2): 312. Bibcode:2004UrbSt..41..299C. doi:10.1080/0042098032000165262. S2CID 153639889.

- ^ a b c Bogart, William (1993). "'What Big Teeth You Have!': Identifying the Motivations for Exclusionary Zoning". Urban Studies. 30 (10): 1669–1681. Bibcode:1993UrbSt..30.1669B. doi:10.1080/00420989320081651. S2CID 153392891.

- ^ a b Ihlanfeldt, Keith (2004). "Exclusionary Land-use Regulations within Suburban Communities: A Review of Evidence and Policy Prescriptions". Urban Studies. 41 (2): 261–283. Bibcode:2004UrbSt..41..261I. doi:10.1080/004209803200165244. S2CID 154395832.

- ^ Ellen, Ingrid (2000). Sharing America's Neighborhoods. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 4.

- ^ Pendall, Rolf (2000). "Local Land Use Regulation and the Chain of Exclusion". Journal of the American Planning Association. 66 (2): 125–142. doi:10.1080/01944360008976094. S2CID 153422286.

- ^ Green, Richard (1999). "Land Use Regulation and the Price of Housing in a Suburban Wisconsin County". Journal of Housing Economics. 8 (2): 144–159. doi:10.1006/jhec.1999.0243.

- ^ Malpezzi, Stephen (1996). "Housing Prices, Externalities, and Regulation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas". Journal of Housing Research. 7 (2): 230.

- ^ a b c d Rothwell, Jonathan. "Housing Costs, Zoning, and Access to High- Scoring Schools" (PDF). Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings.

- ^ Flynn, Jams (1999). "Searching for Justice: The Discovery of IQ Gains Over Time". American Psychologist. 54 (1): 12. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.54.1.5.