Expansion of Jerusalem in the 19th century (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

19th-century event in the Levant

Jerusalem in 1873, shown in three dimensions.

The expansion of Jerusalem outside of the Old City walls, which included shifting the city center to the new neighborhoods, started in the mid-19th century and by the early 20th century had entirely transformed the city. Prior to the 19th century, the main built up areas outside the walls were the complex around King David's Tomb on the southern Mount Zion, and the village of Silwan.

In the mid-19th century, with an area of only one square kilometer, the Old City had become overcrowded and unsanitary, with rental prices on a constant rise.[1] In the mid-1850s, following the Crimean War, institutions including the Russian Compound, Kerem Avraham, the Schneller Orphanage, Bishop Gobat school and the Mishkenot Sha'ananim compound, marked the beginning of permanent settlement outside Jerusalem's Old City walls.[1][2]

In 1855, Johann Ludwig Schneller, a Lutheran missionary who came to Jerusalem at the age of 34, bought a plot of land outside the Old City walls when the area was a complete wilderness. He built a house there but was forced to move his family back inside the walls after several attacks by marauders. When the Ottomans erected outposts along Jaffa Road, between Jerusalem and the port city of Jaffa, and armed guards on horseback patrolled the road, the family returned.[3]

The public institutions[_which?_] were followed by the development of two philanthropically supported Jewish neighborhoods, Mishkenot Sha’ananim and Mahane Israel.[1]

1865 map of Jerusalem

Mishkenot Sha’ananim (Hebrew: משכנות שאננים) was the first Jewish neighborhood built outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem, on a hill directly across from Mount Zion.[4] It was built by Sir Moses Montefiore in 1860 as an almshouse, paid for by the estate of a wealthy Jew from New Orleans, Judah Touro.[5] Since it was outside the walls and open to Bedouin raids, pillage and general banditry rampant in the region at the time, the Jews were reluctant to move in, even though the housing was luxurious compared to the derelict and overcrowded houses in the Old City.[6] As an incentive, people were paid to live there, and a wall was built around the compound with a heavy door that was locked at night.[7] The name of the neighborhood was taken from the Book of Isaiah 32🔞 "My people will abide in peaceful habitation, in secure dwellings and in quiet resting places."[5]

Mahane Israel (Hebrew: מחנה ישראל), founded in 1867, was the second Jewish neighborhood to be built outside the walls of the Old City.[8] Mahane Israel was a "communal neighborhood" and was built by and for Maghrebi Jews.

Nahalat Shiv'a was the third residential neighborhood built outside the city walls. It was founded in 1869 as a cooperative effort by seven Jerusalem families who pooled their funds to purchase the land and build homes. Lots were cast and Yosef Rivlin won the right to build the first house in the neighborhood.[8]

The neighborhoods that make up the Nachlaot district were established outside the walls in the late 1870s. The first was Mishkenot Yisrael, built in 1875. The name comes from a biblical verse (Numbers 24:5): "How goodly are thy tents, O Jacob/Thy dwellings, O Israel." Mazkeret Moshe was founded by Sir Moses Montefiore in 1882 as an Ashkenazi neighborhood. Ohel Moshe is a Sephardi neighborhood established alongside it.[9]

In 1875, Nissan Beck founded the Jewish neighborhood Kirya Ne'emana, popularly known as Batei Nissan Bak ("Nissan Beck Houses").[10] Beck bought the land and paid for the construction of the neighborhood, opposite the Damascus Gate of the Old City, under the auspices of Kollel Vohlin.[11] The neighborhood was originally intended for Hasidic Jews, but due to lack of financing, only 30 of the planned 60 houses were constructed.[11][12] The remainder of the land was apportioned to several other groups: Syrian, Iraqi, and Persian Jews.[13] In the 1890s another neighborhood, Eshel Avraham, was erected next to Kirya Ne'emana for Georgian and Caucasian Jews.[14]

Nahalat Shimon was founded in 1891 by Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jewish Kollels, to house poor Yemenite and Sephardic Jews. The land was purchased in 1890 and the first homes were built soon after, housing 20 impoverished families.[15] The cornerstone of the neighborhood was laid in 1890, near the Tomb of Simeon the Just.[16][17]

Based on Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800–1948 by Ruth Kark and Michal Oren-Nordheim (2001). The years refer to the time the neighbourhoods actually started being inhabited, not the land purchase and construction phase.[2]

- 1853: the Bishop Gobat School (est. 1847) moves to a building next to the Protestant Mount Zion Cemetery

- 1855: British Consul James Finn builds the main house at Abraham's Vineyard (Hebrew: Kerem Avraham), the farm he established for Jewish Jerusalemites

- 1855–1856: Johann Ludwig Schneller builds himself a family house, the nucleus of the Syrian Orphanage or Schneller Orphanage, which would take shape in 1860–61

- 1860: the Mishkenot Sha'ananim Jewish neighbourhood is built by Moses Montefiore

- 1860–1864: the Russian Compound's first building, the women's hospice is being built, followed until 1903 by all the rest

- 1864: Aga Rashid Nashashibi builds his residence, now known as Ticho House

- 1865–1879: the Mahaneh Yisra'el Jewish neighbourhood

- 1865–1890s: the Husaini Neighborhood, Muslim Arab, starting in 1865–76 with the villa of Rabbah Effendi al-Husaini

- 1869: the Nahalat Shiv'a Jewish neighbourhood

- 1870s: the Mas'udiya Muslim Arab neighbourhood

- 1872–1876: the "Georgian Houses" Jewish neighbourhood facing Damascus Gate

- 1873: the German Colony gets started with individual houses; the Templer colony follows in 1878

- 1873: the Beit David Jewish neighbourhood (Yanover Houses)

- 1874–1875: the Mea Shearim Jewish neighbourhood

- 1875: the Even Yisrael Jewish neighbourhood, now part of Nachlaot

- 1875–1876: the Mishkenot Yisrael Jewish neighbourhood, now part of Nachlaot

- 1880s: the Deir Abu Tor mixed Arab neighbourhood

- 1880s: the Catholic "French Colony": Saint-Louis Hospital (1881–1883), Notre Dame de France Hospice (1888–1904)

- 1882: the American-Swedish Colony, Christian Protestant

- 1882: the Mazkeret Moshe Jewish neighbourhood, now part of Nachlaot

- 1882: the Ohel Moshe Jewish neighbourhood, now part of Nachlaot

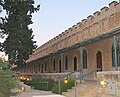

Mishkenot Sha'ananim guesthouse, restored historical building

Nachlaot, Street of the Stairs, Nahalat Ahim

Kerem Avraham, The Christian entrance, founded in 1855.

Meah Shearim, The fifth neighberhood built outside of the old city.

- ^ a b c Glass, Joseph B.; Kark, Ruth (2007). Sephardi entrepreneurs in Jerusalem: the Valero family 1800-1948. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House. p. 174. ISBN 9789652293961. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ a b Kark, Ruth; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948. Israel studies in historical geography. Wayne State University Press. pp. 74, table on p.82-86. ISBN 9780814329092. Retrieved 23 August 2021. The beginning of construction outside the Jerusalem Old City in the mid-19th century was linked to the changing relations between the Ottoman government and the European powers. After the Crimean War, various rights and privileges were extended to non-Muslims who now enjoyed greater tolerance and more security of life and property. All of this directly influenced the expansion of Jerusalem beyond the city walls. From the mid-1850s to the early 1860s, several new buildings rose outside the walls, among them the mission house of the English consul, James Finn, in what came to be known as Abraham's Vineyard (Kerem Avraham), the Protestant school built by Bishop Samuel Gobat on Mount Zion; the Russian Compound; the Mishkenot Sha'ananim houses; and the Schneller Orphanage complex. These complexes were all built by foreigners, with funds from abroad, as semi-autonomous compounds encompassed by walls and with gates that were closed at night. Their appearance was European, and they stood out against the Middle-Eastern-style buildings of Palestine.

- ^ "A guide to buildings in Jerusalem". Aviva Bar-Am for The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ^ "Mishkenot Sha'ananim". Jewish Virtual Library. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- ^ a b Dudman, Helga (1982). Street People. The Jerusalem Post/Carta (1st ed.), Hippocrene Books (2nd ed.). pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-965-220-039-6. Not available on Google Books as of August 2021.

- ^ "Jerusalem architectural history". islamic-architecture.info. Archived from the original on 2012-08-03. Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ "Yemin Moshe and Mishkenot Sha'ananim". Pinhas Baraq for The Jewish Agency for Israel's Department for Jewish Zionist Education. Archived from the original on 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- ^ a b "The Dawn of Modernity - The Beginnings of the New City". Jerusalem: Life Throughout the Ages in a Holy City (course outline). Ramat Gan: Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies, Bar-Ilan University. 1997. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "Jerusalem Architecture in the late Ottoman Period". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Eisenberg, Ronald L. (2006). The Streets of Jerusalem: Who, What, why. Devora Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 1932687548.

- ^ a b Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua (1979). עיר בראי תקופה: ירושלים החדשה בראשיתה [_A City Reflected in its Times: New Jerusalem – The Beginnings_] (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Publications. p. 163.

- ^ Rossoff, Dovid (2001). Where Heaven Touches Earth: Jewish life in Jerusalem from medieval times to the present. Feldheim Publishers. p. 304. ISBN 0-87306-879-3.

- ^ Ben-Arieh (1979), p. 257.

- ^ Ben-Arieh (1979), p. 165.

- ^ "13 New Jewish Homes in Jerusalem". Arutz Sheva. 7 February 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Tagger, Mathilde A.; Kerem, Yitzchak (2006). Guidebook for Sephardic and Oriental genealogical sources in Israel. Bergenfield, NJ: Avotaynu Inc. p. 44. ISBN 9781886223288. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Glass & Kark (2007), p. 254 (as of 23 August 2021 not accessible via Google Books)