Fenner Brockway (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

British politician (1888–1988)

| The Right HonourableThe Lord Brockway | |

|---|---|

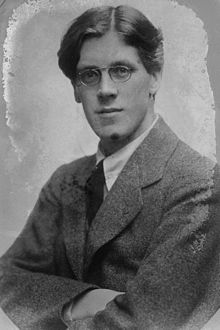

Portrait of Brockway, circa 1910–1915. Portrait of Brockway, circa 1910–1915. |

|

| General Secretary of the Independent Labour Party | |

| In office1933–1939 | |

| Preceded by | John Paton |

| Succeeded by | John McNair |

| Chairman of the Independent Labour Party | |

| In office1931–1933 | |

| Preceded by | James Maxton |

| Succeeded by | James Maxton |

| Member of the House of LordsLord Temporal | |

| In office17 December 1964 – 28 April 1988Life Peerage | |

| Member of Parliamentfor Eton and Slough | |

| In office23 February 1950 – 25 September 1964 | |

| Preceded by | Benn Levy |

| Succeeded by | Anthony Meyer |

| Member of Parliamentfor Leyton East | |

| In office30 May 1929 – 7 October 1931 | |

| Preceded by | Ernest Edward Alexander |

| Succeeded by | Frederick Mills |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Archibald Fenner Brockway(1888-11-01)1 November 1888Calcutta, British India |

| Died | 28 April 1988(1988-04-28) (aged 99) |

| Political party | Independent Labour Party |

| Other politicalaffiliations | Labour Party |

| Spouses | Lilla Harvey-Smith (m. 1914; div. 1945) Edith Violet King (m. 1946) |

| Children | 5 |

Archibald Fenner Brockway, Baron Brockway (1 November 1888 – 28 April 1988) was a British socialist politician, humanist campaigner and anti-war activist.

Early life and career

[edit]

Brockway was born to Rev. William George Brockway and Frances Elizabeth Abbey in Calcutta, British India.[1] He developed an interest in politics while attending the School for the Sons of Missionaries, then in Blackheath, London (now Eltham College), from 1897 to 1905. In 1908, Brockway became a vegetarian.[2] Several decades later, during a debate in a House of Lords on animal cruelty, he said: "I am a vegetarian and I have been so for 70 years. On the whole, I think, physically I am a pretty good advertisement for that practice."[3]

After leaving school, he worked as a journalist for newspapers and journals including The Quiver, the Daily News and the Christian Commonwealth. In 1907, Brockway joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and was a regular visitor to the Fabian Society. He was appointed editor of the Labour Leader (the newspaper of the ILP, later called the New Leader) and was, by 1913, a committed pacifist. He opposed sending troops to France during the First World War and, through his position as editor of the Labour Leader, was outspoken in his views about the conflict.

On 12 November 1914, he published an appeal for men and women of the military age to join him in forming the No-Conscription Fellowship to campaign against the possibility of the government attempting to introduce conscription in Britain. Brockway acknowledged his wife, Lilla Brockway, had the foresight "that those who intended to refuse military service should band themselves together". Lilla acted as provisional secretary at their cottage in Derbyshire until the beginning of 1915, when the membership had grown so large that it had become necessary to open an office in London.[4] In London, Catherine Marshall became the Fellowship's political secretary since she was adept at political strategy as the Parliamentary Secretary of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.[4] The No-Conscription Fellowship produced a weekly newspaper, The Tribunal, which was suppressed; through the activity of Joan Beauchamp it continued production, although her refusal to divulge the name of the printer caused her to be charged with contempt of court and held in custody for 10 days.[4] The offices of the Labour Leader were raided in August 1915 and Brockway was charged with publishing seditious material. He pleaded not guilty and was acquitted in court. In 1916 Brockway was again arrested, this time for distributing anti-conscription leaflets. He was fined, and after refusing to pay the fine, was sent to Pentonville Prison for two months.[5]

Shortly after his release, Brockway was arrested for a third time for his refusal to be conscripted, after being denied recognition as a conscientious objector. He was handed over to the Army and court-martialled for disobeying orders. As if a traitor, he was held for a night in the Tower of London, in a dungeon under Chester Castle and in Walton Prison, Liverpool, where he edited an unofficial newspaper, the Walton Leader, for conscientious objectors in the prison. This led to his being disciplined, which in turn led to a 10-day prison strike by conscientious objectors before he was transferred to Lincoln Jail, where he spent some time in solitary confinement until finally released in 1919. In October 1950 he revisited the jail with Éamon de Valera, the Irish statesman.[6]

Following his release, Brockway became an active member of the India League, which advocated Indian independence. He became secretary of the ILP in 1923 and later its chairman. Years later, the Government of India honoured him with the third highest civilian award of the Padma Bhushan in 1989.[7]

Political activities, 1924–1935

[edit]

Brockway stood for Parliament several times, including at Lancaster in 1922 and against Winston Churchill at Westminster Abbey in a 1924 by-election. In 1926, he became the first chairperson of War Resisters' International, serving in this post until 1934.[5] Brockway was a member of the League against Imperialism created in Brussels in 1927.

As the Nazi Party was getting more and more popular support, Brockway arrived in Poland after being invited there by The Independent Socialist Party of Poland, with Joseph Krok as one of its leaders. Brockway tried to warn the public of the Nazi threat, but he was instructed by the British Embassy in Warsaw NOT to mention "the minority issue" of Poland. Later Brockway met with Antonov Obisenko, USSR ambassador to Poland.[8]

At the 1929 general election, he was elected as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Leyton East as a Labour Party candidate. He polled 11,111 votes and, immediately after the election, the Liberal candidate announced that Brockway had converted him to socialism. His convictions brought him into difficulties with the Labour Party. He was also outspoken in Parliament, and was once "named" (suspended) by the Speaker while demanding a debate on India at Prime Minister's Questions.[9][10]

In 1931 Brockway lost his seat and the following year he disaffiliated from the Labour Party along with the rest of the ILP. He stood unsuccessfully for the ILP in the 1934 Upton by-election (Upton was a division of West Ham), placed a remote third with only a 3.5% share of the votes cast, and in Norwich in the 1935 election. He also wrote a book on the arms trade, The Bloody Traffic, published by Gollancz Ltd in 1934. According to David Howell, after 1932 Brockway "sought to articulate a socialism distinct from the pragmatism of Labour and the Stalinism of the Communist Party".[11]

In Brockway's science fiction novel, Purple Plague (1935), a sea liner is quarantined for a decade as a result of a plague. An egalitarian society emerges.[12]

Despite Brockway's previous pacifist commitment, he resigned from War Resisters' International, explaining:

If I were in Spain at this moment I should be fighting with the workers against the Fascists forces. I believe it to be the correct course to demand that the workers shall be provided with the arms which are being sent so freely by the Fascist powers to their enemies. I appreciate the attitude of the pacifists in Spain who, whilst wishing the workers success, feel that they must express their support in constructive social service alone. My difficulty about that attitude is that if anyone wishes the workers to be triumphant he cannot, in my view, refrain from doing whatever is necessary to enable that triumph to take place.[13]

He assisted in the recruitment of British volunteers to fight the fascist forces of Francisco Franco in Spain through the ILP Contingent. He sailed to Calais in February 1937 and was believed to have been destined for Spain.[14] Among those who went to Spain was Eric Blair (better known as George Orwell), and Brockway wrote a letter of recommendation for Blair to present to the ILP representatives in Barcelona. Following the Spanish Civil War, Brockway advocated public understanding of the conflict. He wrote a number of articles about the conflict and was influential in getting Orwell's Homage to Catalonia published.[15]

Notwithstanding his support for British participation in the Second World War, Brockway served as chair of the Central Board for Conscientious Objectors throughout the war, and continued to serve as chair until his death.[16] He also sought to re-enter Parliament, unsuccessfully contesting wartime by-elections for the ILP at Lancaster in 1941 and Cardiff East in 1942.[17]

After the Second World War

[edit]

In May 1946, Brockway toured the British occupation zone in Germany as an accredited war correspondent, meeting German socialists and reporting on living conditions there; he wrote about the visit in German Diary, published by the Left Book Club.[18]

Brockway appeared in Hitler's Black Book that contained a list of British subjects and residents who would have been subject to arrest had the Nazis successfully invaded the UK.[19] The contents of the book were not publicly known until after the Second World War.

Brockway later rejoined the Labour Party. After the 1950 general election he returned to the House of Commons, following an absence of more than 18 years, as the MP for Eton and Slough.

On 28 March 1950, he forced a debate in the House of Commons on the decision by the Labour government of the UK to banish Seretse Khama from his homeland, the British protectorate which became Botswana. The British government also withheld recognition of Khama as the Chief of the Bamangwato people, because he had married an Englishwoman. The marriage was an affront to the apartheid South African minority government under D. F. Malan, which, it became very clear, the UK government wished to appease.[20]

In 1951, Brockway was one of the four founders of the charity War on Want, which fights global poverty. He helped establish the Congress of Peoples Against Imperialism (est. 1945), an organisation he continued to work with throughout the 1950s.[21] His activities there included protesting against the response of the government to the Mau Mau Uprising in the British Kenya Colony.[22] In this area, he was a part of the larger Movement for Colonial Freedom. From the late 1950s he regularly proposed legislation in Parliament to ban racial discrimination, only to be defeated each time. He strongly opposed the use or possession of nuclear weapons by any nation and was a founding member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[23]

On 18 July 1961, Brockway was chosen by Speaker Harry Hylton-Foster to ask the first question at the very first Prime Minister's Questions in the current format.[24]

Brockway was a prominent member of the British Humanist Association and South Place Ethical Society where he became an Appointed Lecturer during the 1960s.[25] He gave the 1986 Conway Memorial Lecture on 21 May 1986. The Lecture was titled M D Conway: His Life and Message For Today and was chaired by Michael Foot.[26] The Brockway Room at Conway Hall in London is named after him.

Former KGB officer Oleg Gordievsky, who defected to the UK in 1985, alleged that Brockway had been a "confidential contact" of the KGB and had "accepted a great deal of hospitality from Soviet intelligence".[27]

Brockway narrowly lost his seat in the House of Commons at the 1964 election, despite the national swing to Labour at that election, as he was portrayed by his opponents as being the principal cause of immigrants from the West Indies settling in Slough.[28] He subsequently was created a life peer on 17 December 1964, taking the title Baron Brockway, of Eton and of Slough in the County of Buckingham,[29] and took a seat in the House of Lords.

Brockway continued to campaign for world peace and was for several years the chairman of the Movement for Colonial Freedom. Other important posts held by him include the Presidency of the British Council for Peace in Vietnam, and membership of the Advisory Council of the British Humanist Association.[30] The World Disarmament Campaign was founded by Brockway in 1979, together with Philip Noel-Baker, to work for the implementation of the policies agreed at the 1978 Special Session on Disarmament of the UN General Assembly.[31]

Brian Harrison recorded an oral history interview with Brockway, in April 1980, as part of the Suffrage Interviews project, titled Oral evidence on the suffragette and suffragist movements: the Brian Harrison interviews.[32] Brockway discusses his introduction to socialism, through Keir Hardie, and his interest in women's suffrage.

Brockway died on 28 April 1988, aged 99. He was some six months shy of his centenary.[15] Brockway had been twice married: firstly in 1914 (divorced 1945) to Lilla, daughter of the Rev. W. Harvey-Smith; secondly in 1946 to Edith Violet King. By his first marriage, he had four daughters, and by his second, he had a son.[33][34]

While he was in prison, Brockway met the prominent peace activist Stephen Henry Hobhouse, and in 1922 they co-authored English prisons to-day: being the report of the Prison system enquiry committee, a devastating critique of the English prison system which resulted in a wave of prison reform that has continued to this day.[35] Brockway wrote more than twenty other books on politics and four volumes of autobiography.[15][36][37]

- 1915: The devil's business; a play and its justification

- 1915: Is Britain blameless?

- 1916: Socialism for pacifists

- 1918?: All about the I.L.P.

- 1919: The recruit: a play in one act

- 1927: A week in India

- 1928: A new way with crime

- 1930: The Indian crisis

- 1931: Hands off the railmen's wages!

- 1932: Hungry England

- 1933: The bloody traffic

- 1934: Will Roosevelt succeed? A study of Fascist tendencies in America

- 1935: Purple Plague: A Tale of Love and Revolution (fiction)

- 1937: The truth about Barcelona

- 1938: Pacifism and the left wing

- 1938: Workers' Front

- 1940 :Socialism can defeat Nazism: together with Who were the friends of fascism, with John McNair

- 1942: The way out

- 1942: Inside the left; thirty years of platform, press, prison and Parliament

- 1942?: The C.O. and the community

- 1944: Death pays a dividend, with Frederic Mullally

- 1946: German diary

- 1946: Socialism over sixty years: the life of Jowett of Bradford (1864–1944)

- 1949: Bermondsey story; the life of Alfred Salter

- 1953?: Why Mau Mau?: an analysis and a remedy

- 1963: Outside the right; a sequel to 'Inside the left.', with George Bernard Shaw

- 1963: African socialism

- 1967: This shrinking explosive world: a study of race relations

- 1973: The colonial revolution

- 1977: Towards tomorrow: the autobiography of Fenner Brockway

- 1980: Britain's first socialists: the Levellers, Agitators, and Diggers of the English Revolution

- 1984: Bombs in Hyde Park?

- 1986: 98 not out

Statue of Fenner Brockway in Red Lion Square, near Gray's Inn Road, London

Brockway's life and legacy are celebrated in his old constituency of Slough with the now annual FennerFest, a community arts and culture festival.

A statue of Brockway stands at the entrance to Red Lion Square Park in Holborn, London; it was funded by many involved in the Commonwealth independence movements he supported and was expected to be unveiled after his death. However, he achieved such longevity that it was likely that the original Planning Permission to erect it would run out, causing problems to renew the process. It was decided to ask him to unveil it, he being one of the few private individuals, as opposed to Heads of State to do so. It was damaged (an arm was broken off) by a falling tree in the Great Storm of 1987. The refurbished and insured statue was installed shortly after his death.

A close in the town of Newport in southern Wales is named after him.

- ^ "The Papers of Fenner Brockway". Archivesearch. Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge University.

- ^ "House of Lords Debate: Live Food Amimals for Slaughter". Hansard. 5. 397. cc387. 7 December 1978. Retrieved 25 August 2014. Lord BROCKWAY: My Lords, perhaps I should begin by declaring an interest. I am a vegetarian and I have been so for 70 years...

- ^ Warry, Richard (5 September 2017). "Jeremy Corbyn and other famous vegetarian politicians". BBC News. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Brockway, Fenner (1942). "Chapter Nine; Organising War Resisters". Inside the left: thirty years of platform press, prison and Parliament. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. pp. 66, 68, and 71.

- ^ a b "First World War.com - Who's Who - Fenner Brockway". Firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Lincolnshire Echo, 9 October 1950.

- ^ "Padma Awards" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Joseph Krok, Under the flag of three revolutions - Vol.II, Tel Aviv 1970, pp. 428-429 [heb]

- ^ The Manchester Guardian, 18 July 1930, p. 11.

- ^ "Questions to the Prime Minister". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 241. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 17 July 1930. col. 1462–1469.

- ^ Howell, David, "Brockway, (Archibald) Fenner, Baron Brockway" in H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (eds), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: From the earliest times to the year 2000. ISBN 019861411X (Volume Seven, pp. 765–6).

- ^ "Fenner Brockway". Fantastic-writers-and-the-great-war.com. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Prasad, Devi, War is a Crime against Humanity: the story of War Resisters' International, London: War Resisters' International, 2005.

- ^ National Archive; Spanish Civil War files.

- ^ a b c Spartacus Educational: Fenner Brockway profile. Archived 17 April 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kramer, Ann, Conscientious Objectors of the Second World War, Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books, 2013.

- ^ "Brockway". Who's Who. A & C Black. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U162354. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Brockway, Fenner (1946). German diary. London: Gollancz.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Fenner Brockway". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Dutfield, Michael (1990). A Marriage of Inconvenience. London: Unwin Hyman.

- ^ Howell, David (23 September 2004). "'Brockway, (Archibald) Fenner, Baron Brockway (1888–1988)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39849. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Brockway, Fenner (1955). African Journeys. London: The Bodley Head.

- ^ White, Aidan (3 October 1986). "The graduate from the old school". The Guardian. p. 19.

- ^ "Ambassador to South Africa". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. 18 July 1961. col. 1052–1053.

- ^ Mackillop, I. D. (1986). The British Ethical Societies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521266726. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "M D Conway: His Life and Message For Today". Conway Hall Ethical Society. 21 May 1986. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben (2019); The Spy and the Traitor: The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War, Penguin Books Ltd., ISBN 0241972132

- ^ Bob Armstrong, Labour Party Aid to Fenner in the 1964 election.

- ^ "No. 43519". The London Gazette. 18 December 1964. p. 10823.

- ^ "Fenner Brockway". Humanist Heritage. Humanists UK. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "World Disarmament Campaign".

- ^ London School of Economics and Political Science. "The Suffrage Interviews". London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ Ann Evory, Pamela Dear, Contemporary Authors: A Bio-bibliographical guide to current writers, Gale Group, 2000, p. 10.

- ^ A. Thomas Lane (ed.), Biographical Dictionary of European Labour Leaders, Greenwood Press, 1995, p. 147.

- ^ "Rosa and Stephen Hobhouse and Homeopathy | Sue Young Histories". Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Results for 'Fenner Brockway' [WorldCat.org]". Worldcat.org. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ "Fenner Brockway - Making Britain". Open.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Brockway, Fenner Inside the Left: Thirty Years of Platform, Press, Prison and Parliament, London: George Allen and Unwin, 1942 [reprint: Spokesman, 2010].

- Fenner Brockway: 1960 Racial Discrimination Bill UK Parliament Living Heritage

- Papers of Fenner Brockway at the Churchill Archives Centre

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Fenner Brockway

- Biography at Peace Pledge Union

- Fenner Brockway talking in 1981 about his early involvement with socialism

- Fenner Brockway at Library of Congress, with 34 library catalogue records

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byErnest Edward Alexander | Member of Parliament for East Leyton 1929–1931 | Succeeded byFrederick Mills |

| Preceded byBenn Levy | Member of Parliament for Eton and Slough 1950–1964 | Succeeded byAnthony Meyer |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded byJames Maxton | Chairman of the Independent Labour Party 1931–1933 | Succeeded byJames Maxton |

| Preceded byJohn Paton | General Secretary of the Independent Labour Party 1933–1939 | Succeeded byJohn McNair |

| Non-profit organization positions | ||

| Preceded by_New position_ | Chair of War Resisters' International 1926–1934 | Succeeded byArthur Ponsonby |

| Media offices | ||

| Preceded byJ. T. Mills | Editor of the Labour Leader 1912–1916 | Succeeded byKatharine Glasier |

| Preceded byH. N. Brailsford | Editor of the New Leader 1926–1929 | Succeeded byErnest E. Hunter |

| Preceded byJohn Paton | Editor of the New Leader 1931–1946 | Succeeded byGeorge Stone andF. A. Ridley |