Grand Model for the Province of Carolina (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Province of Carolina

The Grand Model (or "Grand Modell" as it was spelled at the time) was a utopian plan for the Province of Carolina, founded in 1670 (354 years ago) (1670). It consisted of a constitution coupled with a settlement and development plan for the colony. The former was titled the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina. The word "constitutions" (in the plural) was synonymous with "articles". The document was composed of 120 constitutions, or articles. The settlement and development plan for the colony consisted of several documents, or "instructions", for guiding town and regional planning as well as economic development.

Both the Fundamental Constitutions and the development plan were drafted by the English liberal philosopher John Locke while working for the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, the eight noblemen who held the royal charter to settle the colony. Locke was also a personal assistant to Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Proprietor who became the Earl of Shaftesbury soon after the principal elements of the Grand Model were drafted. Ashley Cooper is considered the founder of Carolina, thus the Grand Model may also be called the Ashley Cooper Plan.[1] Today the term Grand Model is used more restrictively in Charleston, South Carolina to refer to the original planned area of the city.[2]

Anthony Ashley Cooper oversaw Locke's drafting of the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina during the first decade of the Restoration, a time when the failure of the Commonwealth of England was fresh in mind. During the Commonwealth period he had served in the government of Oliver Cromwell and participated in reviewing English laws and drafting the nation's first formal constitution. Before that, English constitutional law was based on ancient constitutional documents such as Magna Carta. The experience led Ashley Cooper to see value in adopting a formal constitution for the Province of Carolina.[3]

Ashley Cooper aided the restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660 and the king reciprocated by granting the charter for Carolina to Ashley Cooper and the colony's other Lords Proprietors. Nevertheless, Ashley Cooper strongly believed in the English tradition of common law and balanced government, a system sometimes called the "Ancient Constitution", wherein nobility played a leading role.[4] The Fundamental Constitutions was designed to formalize a "Gothic" system of balanced government in the new province. Although described as feudalism by some authorities, the system was arguably more advanced by virtue of its constitution and emphasis on basic rights and reciprocal benefits among classes. It was nevertheless a pre-Enlightenment system predicated on class hierarchy.[5]

Settlement and development plan

[edit]

The Fundamental Constitutions provided a framework for urban and regional development consistent with and supportive of the plan for governance and economic development. Once settlement began in 1670 a series of "instructions" were transmitted to the colonists with details that fleshed out areas that were not addressed by the Fundamental Constitutions.[6]

The design of towns in Carolina was influenced by the intensive planning that went on in London after the Great Fire of 1666. The government of Charles II solicited plans to rebuild the city, and inspired designs were submitted by architect Christopher Wren, scientist Robert Hooke, cartographer Richard Newcourt, and landscape planner and polymath John Evelyn. Their designs influenced city planning in the areas of public health and safety, land use efficiency, and urban aesthetics.[7][8]

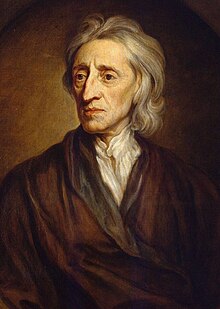

John Locke (1697). Portrait by Godfrey Kneller.

Locke first became involved with Carolina as a personal assistant to Anthony Ashley Cooper, a relationship that began in 1666. Soon afterward he became secretary to the Lords Proprietors and began drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina and associated planning materials. The precise extent to which Locke shaped the substance of the Fundamental Constitutions is unknown, but he was undoubtedly guided at least on a general level by Ashley Cooper.[9]

Locke's position with the Lords Proprietors might be described as that of "chief planner" for Carolina. He drafted development standards for towns as well as an illustrative plan that he included in his instructions to the colonists. His urban plan provided detailed standards for block size, lot size, street width, waterfront setbacks, and other standards similar to modern planning and zoning ordinances.[10]

Locke also wrote guiding principles for regional development that were remarkably similar to principles of modern planning, including aspects of sustainable development and smart growth. Such aspects include, a) consistency of development practices with the general plan (Fundamental Constitutions); b) concurrent provision of infrastructure with land development; and compactness of development to promote efficient use of land and access to markets.[11]

Slavery and the Grand Model

[edit]

Locke famously denounced slavery in the first sentence of his Two Treatises of Government, then proceeded to develop the new idea of natural equality. Since the Grand Model anticipated slavery, Locke has been labeled a hypocrite by some scholars for designing Carolina and then continuing to be associated with the venture after writing the famous indictment of slavery. While the Fundamental Constitutions contains an article establishing slavery, one can find no references to slavery in the detailed planning documents over which Locke had the most control. Thus while Locke and Ashley Cooper anticipated that Carolina would have slaves, as did most other colonies, it is unlikely that they anticipated that it would become fundamentally dependent on slavery (i.e., a "slave society") as later happened.

On the other hand, it must be admitted that Locke did have a certain financial interest in the institution of slavery. Along with Anthony Earl of Shaftesbury, Locke was a founding shareholder in the Royal African Company, chartered in 1672 by King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland.[12] Between 1672 and 1731, the Royal African Company transported 187,697 enslaved people on company-owned ships to British colonies in the Caribbean and North America.

The Grand Model allocated more land (60 percent) and representation to "the people" than to the nobility, suggesting that yeoman farmers were envisioned ultimately to become the backbone of the colony. Nevertheless, a slave-owning elite was also part of the formula from the beginning. Shaftesbury viewed slavery as a vital factor for principal estates. In December, 1671, he advised against bringing too many of "the poorer sort" to the colony until "men of estates" could first "stock the country with Negroes, cattle, and other necessarys".[13]

Barbadian Adventurers

[edit]

The transformation of Carolina from a colony with slaves to a slave colony, and later a slave society, began when slaveowners from Barbados, starting with the "Barbadian Adventurers" led by such individuals as John Colleton and John Yeamans, became the dominant force in Carolina politics during the 1680s. Barbados had evolved into a slave colony with a majority slave population during that period. The Grand Model was informally modified by the Barbadians, who took the titles of nobility, but replaced Ashley Cooper's enlightened aristocracy with a self-serving oligarchy. The new plantation elite exercised little regard for balanced government, class reciprocity, or humane treatment of the servant and slave classes.[14] The Barbados Slave Code was also brought with the Adventurers to codify the legality of slavery in Carolina, and was adapted in surrounding colonies.[15]

The Grand Model and America's planning tradition

[edit]

The following components of the Grand Model influenced subsequent colonial town planning:[16]

- Regular settlement rather than scattered pattern of development

- Town, suburban, and country lot allocation

- Town planned and laid out in advance

- Wide streets laid out in geometric form usually within a square mile grid

- Public squares

- Standardized, rectangular lots

- Reserved lots for civic purposes

- Separation of town and country with a common or greenbelt.

Philadelphia and Savannah were among the American cities adopting these components of the Grand Model.[17] The Georgia Trustees acknowledged the influence of the Grand Model: "We are indebted to the Lord Shaftsbury, and that truly wise man Mr. Locke," they wrote, "for the excellent laws which they drew up for the first settlement of Carolina."[18]

While Locke's plan for Charles Town (Charleston, SC) and other cities of Carolina was only partially implemented, its grid, civic spaces, and wide streets became common features of American city planning, due in large part to the examples of Philadelphia and Savannah (see Oglethorpe Plan).

Influence on American political culture

[edit]

The Grand Model influenced the formation of southern, traditionalistic political culture. The model, modified by slaveowners from the Caribbean, created a formal slave society that became a model for the future states of the Deep South. The Grand Model contributed a stable plantation land use pattern and a formal social hierarchy led by nobility. The Barbadian slaveowners added large scale monoculture (sugar cane in Barbados, rice in Carolina) and a more rigid system of government and social control by a slaveowning elite. The blended system in Carolina established a pattern that was followed throughout the eighteenth century, and ultimately proved well-suited to King Cotton.[19]

- ^ Famous plans are often named after the person who conceived them, e.g., the Oglethorpe Plan, the L'Enfant Plan

- ^ Steedman, "How the City Grew".

- ^ For a contemporary perspective on Ashley Cooper's career, see, Spurr, John, Chapter 1; Marshall, Alan, Chapter 2; and Leng, Thomas, Chapter 5 in Spurr, Anthony Ashley Cooper, First Earl of Shaftesbury, 1621–1683. For a complete and authoritative biography, see, Haley, The First Earl of Shaftesbury.

- ^ Mansfield, Andrew (2021-09-03). "The First Earl of Shaftesbury's Resolute Conscience and Aristocratic Constitutionalism". The Historical Journal. 65 (4): 969–991. doi:10.1017/s0018246x21000662. ISSN 0018-246X. S2CID 239706680.

- ^ See Pocock, p. 94, for use of the word "gothic"

- ^ Shaftesbury, 322, 367, 405.

- ^ Wilson, 100-103.

- ^ For background on Hooke's role, see Cooper, Michael, A More Beautiful City: Robert Hooke and the Rebuilding of London after the Great Fire.

- ^ Wilson, 44-48.

- ^ Wilson, 44-48.

- ^ Wilson, 44-48.

- ^ W. M. Spellman, John Locke, p. 15

- ^ Shaftesbury Papers, 364

- ^ Wilson, Chapter 3

- ^ "Atlantic Virginia: Intercolonial Relations in the Seventeenth Century – EH.net". Retrieved 2024-03-09.

- ^ Home, Of Planting and Planning, 9.

- ^ Home, Of Planting and Planning, 8.

- ^ Martyn, "Reasons for the Establishment of the Colony of Georgia in America," 1732.

- ^ Wilson, Chapter 4.

- Ashley Cooper, Anthony. The Shaftesbury Papers Charleston, SC: South Carolina Historical Society, 2000.

- Cooper, Michael, A More Beautiful City: Robert Hooke and the Rebuilding of London after the Great Fire, Phoenix Mill, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2003.

- Haley, K. H. D. The First Earl of Shaftesbury. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Home, Robert. Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities. London: E & FN Span, 1997.

- Mansfield, Andrew (2021-09-03). "The First Earl of Shaftesbury's Resolute Conscience and Aristocratic Constitutionalism". The Historical Journal: 1–23. doi:10.1017/s0018246x21000662. ISSN 0018-246X

- Martyn, Benjamin. "Reasons for the Establishment of the Colony of Georgia in America," 1732.

- Pocock, J. G. A. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- Spurr, John. "Shaftesbury and the Seventeenth Century." Anthony Ashley Cooper, First Earl of Shaftesbury, 1621–1683. Surrey: Ashgate, 2011.

- Steedman, Marguerite Couturier, "How the City Grew," Charleston County Public Library, https://web.archive.org/web/20151017030645/http://www.ccpl.org/content.asp?catID=6062&parentID= (accessed November 1, 2015).

- Wilson, Thomas D. The Ashley Cooper Plan: The Founding of Carolina and the Origins of Southern Political Culture. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, February, 2016.