Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

German Christian communion hymn

| "Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein" | |

|---|---|

| Christian hymn | |

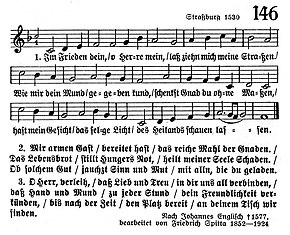

"Im Frieden dein", in Otto Riethmüller's Ein neues Lied, 1932 "Im Frieden dein", in Otto Riethmüller's Ein neues Lied, 1932 |

|

| English | In Your peace, O my Lord |

| Occasion | Communion |

| Text | Johann Englisch and Friedrich Spitta |

| Language | German |

| Based on | Nunc dimittis |

| Meter | 4 4 7 4 4 7 4 4 7 |

| Melody | Wolfgang Dachstein |

| Composed | before 1530 |

| Published | 15301898 |

"Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein" (In Your peace, o my Lord) is a three-stanza German Christian communion hymn. In 1527 the early Reformer Johann Englisch (Johannes Anglicus) wrote two stanzas as a rhyming close paraphase of the Nunc dimittis, or Canticle of Simeon. The hymn is sung to a melody by Wolfgang Dachstein, written before 1530. Friedrich Spitta revised the lyrics in 1898 and added a third stanza. His revision transformed Englisch's prayer of an individual with a focus on a peaceful death to a communal one more about peaceful life in unity.

This version is part of the German Protestant hymnal, Evangelisches Gesangbuch, as EG 222. An ecumenical song, it is also part of the current Catholic hymnal, Gotteslob, as GL 216. It appears in several other hymnals.

The development of the hymn spans four stages within the history of Christianity.[1] Its initial inspiration draws from the account of Jesus being presented at the temple 40 days after his birth, in a ritual of purification depicted in the Gospel of Luke. On that occasion, Simeon praised the light that appeared by the baby. Centuries later, Simeon's canticle became a regular part of the Liturgy of the Hours as the Nunc dimittis, especially connected to the feast of the purification.[2]

Thirdly, during the Reformation, the Nunc dimittis was used as a prayer of thanks after communion, as documented in a Nördlingen liturgy of 1522 and a Strasbourg liturgy of 1524, the latter specifically calling for its use "after the meal" or communion ("nach dem Mahle").[2] The rhyming paraphrase created by Johann Englisch, or Johannes Anglicus [de], first appearing in 1527 on a now-lost leaflet, became a regular part of Strasbourg hymnals from 1530 on.[2] His version retains the theme of the Nunc dimittis, with its ideas of rest in peace after having seen the light of a saviour who came for all people and especially Israel.[3] The hymn is sung to a melody attributed to Wolfgang Dachstein, written before 1530.[4] It is one of three hymns described as _Der Lobgesang Simeonis (Simeon's song of praise) appearing in an 1848 collection of _Schatz des evangelischen Kirchengesangs im ersten Jahrhundert der Reformation ("Treasure of Protestant church singing in the first century of the reformation"). The first two are the Biblical canticle in Martin Luther's translation, and Luther's paraphrase "Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin", followed by "Im Frieden dein". A footnote marks the three songs as also suitable for funerals.[5]

Finally, in 1898, Friedrich Spitta, a Protestant theologian, revised the song and added a third stanza, which is now usually placed between the older stanzas.[6] He shifted the meaning from an individual prayer for a good death to a communal prayer for a meaningful life.[7] The focus is on communion as a way for believers to see the light of Christ and thereby live in peace and unity.[6][4] With additional minor changes, this version of the hymn is part of the German Protestant hymnal, _Evangelisches Gesangbuch, as EG 222.[8][9]

An ecumenical song, it is also part of the current Catholic hymnal, _Gotteslob, as GL 216, in the section "Gesänge – Woche – Gesänge zur Kommunion / Dank nach der Kommunion" (Songs – Week – Communion – Thanks after Communion).[1][4] It appears in several other hymnals.[10]

The text of the hymn is as follows, on the left as in Tucher's 1848 publication which shows Englisch's two stanzas,[3] on the right the text from the current German hymnals:[6]

| Tucher, 1848 | Modern |

|---|---|

| Im Frieden dein,o Herre mein,wollst mich nun ruhen lassen.Als mir ward Bscheidvon dir geseit,so hast mich jetzt begossen,daß mein Gesichtmit Freuden spricht,den Heiland habs gesehen!Ein'n werthen Gastbereitet hastvor allen Völkern große.Der Heiden G'sichtim Licht bericht't,macht sie des Glaubens G'nossen.Ein Lob und Ehr,groß durch dich, Herr,wird Israel ein Volke. | Im Frieden dein,o Herre mein,lass ziehn mich meine Straßen.Wie mir dein Mundgegeben kund,schenkst Gnad du ohne Maßen,hast mein Gesichtdas sel'ge Licht,den Heiland, schauen lassen.Mir armem Gastbereitet hastdas reiche Mahl der Gnaden.Das Lebensbrotstillt Hungers Not,heilt meiner Seele Schaden.Ob solchem Gutjauchzt Sinn und Mutmit alln, die du geladen.O Herr, verleih,dass Lieb und Treuin dir uns all verbinden,dass Hand und Mundzu jeder Stunddein Freundlichkeit verkünden,bis nach der Zeitden Platz bereit'an deinem Tisch wir finden. |

Englisch's lyrics are a close paraphrase of the Nunc dimittis, about being able to go in peace after having seen the light of the Saviour ("Heiland"). Simeon said so after actually seeing the baby Jesus, 40 days after his birth, and for him departing in peace could mean readiness to die. Englisch begins in the first person, addressing God as his Lord ("Herre mein"), who prays to be allowed to rest in God's peace ("Im Frieden dein ... wollst mich nun ruhen lassen").[3]

Spitta transfers the thought to a more general meaning, of travelling one's roads after having seen the light, adding that His mercy is unmeasurable ("ohne Maßen").[7]

The second stanza in Englisch's version is a paraphrase of the second part of Simeon's canticle, mentioning the dear guest ("werthen Gast"), alluding to Jesus, for all people including the heathen, and for the greatness of Israel.[3]

Spitta changes the focus, identifying the singer with the guest (instead of referring to Jesus), invited to a rich meal of mercy ("das reiche Mahl der Gnaden"). The meal offers the bread of life ("Lebensbrot"), which joins the invited believers to God and among each other, a reason to praise, filled with sense and courage ("Sinn und Mut").[7] The heathen and Israel are not mentioned in his version.[11]

The final stanza is a prayer for love and faithfulness in God connecting "us all" ("uns all"), so that hand and mouth will show the friendliness of the Lord, until after this time all may find a seat at his table.[11]

The lyrics follow a pattern of two rhyming short lines followed by a longer line, repeated three times in a stanza, with the three longer lines all rhyming: aabccbddb.[12]

From 1530, the hymn was associated with a melody attributed to Wolfgang Dachstein. The tune has an element often found in Strasbourg melodies, a rhythm of long-short-short-long, here used for the short lines. The first two long lines begin with a long note, followed by a sequence of equally short notes, ending on two long notes.[13] The first line begins with the lowest note and rises a fourth, step by step. The other short lines have similar patterns, such as the equal lines which begin the second and third section, moving a fourth downward. The last section begins an octave higher than the second ends, a feature often found in contemporary Strasbourg melodies, especially by Matthäus Greiter, sometimes accentuating a bar form's _abgesang.[14] The last line, beginning like the first line, is the only one which has a melisma. In Dachstein's composition, it stresses the last word by dotted notes, rising to an octave above the first note.[15] The stressed word in the first stanza is "gesehen" (seen) and in the second "Volke" (people, meaning Israel).[3] Shortly before the end of the melisma, a ligature typical for German melodies of the 16th century moves around ("umspielt") the second to last note, then released to the key note.[15] While it is usually difficult to find a relation between words and music in strophic texts, it can be assumed that peace is expressed by the calm movement, up and down in symmetry. The last rising line might even be experienced as an expression of a vision of God ("Gottesschau"), although it seems unlikely that the composer had that in mind.[14]

The long and complex last line is difficult for congregational singing, and later versions therefore often abbreviate the melisma, in various ways. An 1899 hymnal for Alsace-Lorraine has a version with only the ligature before the end, the version in today's hymnals.[15] However, the first publication of Spitta's text came with Dachstein's melody.[15]

Samuel Mareschall composed a four-part choral setting in 1606, published by Carus-Verlag.[16] Herbert Beuerle composed a setting for three parts in 1953.[17] In 1980, Aldo Clementi wrote a motet for eight voices.[18] Bernhard Blitsch composed a motet for four parts in 2013.[19] Gaël Liardon published an organ work in 2014.[20]

- ^ a b Marti 2011, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Marti 2011, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Tucher 1848, p. 192.

- ^ a b c Mein Gotteslob 2019.

- ^ Tucher 1848, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b c Meesters 2014.

- ^ a b c Marti 2011, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Marti 2011, pp. 8, 11.

- ^ Liederdatenbank 2019.

- ^ Marti 2011.

- ^ a b Marti 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Marti 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Marti 2011, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Marti 2011, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Marti 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Mareshall 2019.

- ^ Beuerle 1953.

- ^ Clementi 2019.

- ^ Blitsch 2019.

- ^ Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein (Liardon, Gaël): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

Marti, Andreas (2011). Herbst, Wolfgang; Alpermann, Ilsabe (eds.). 222 Im Frieden dein, oh Herre mein (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 8–13. ISBN 978-3-64-750302-8.

Meesters, Maria (13 July 2014). "SWR2 Lied zum Sonntag / Im Frieden dein, oh Herre mein". SWR (in German). Retrieved 4 February 2018.

Tucher, Gottlieb Freiherr von (1848). Schatz des evangelischen Kirchengesangs im ersten Jahrhundert der Reformation (in German). Breitkopf und Härtel. pp. 192–193.

"Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein". Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (in German). Retrieved 2 February 2019.

"Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein (L) / Gesänge – Woche – Gesänge zur Kommunion / Dank nach der Kommunion". Carus-Verlag (in German). Retrieved 2 February 2019.

Im Frieden dein o Herre mein : mottetto a otto voci : 1980 (in Italian). Edizioni Suvini Zerboni. 1985. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

"Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein". liederdatenbank.de (in German). Retrieved 13 January 2019.

"Samuel Mareschall / Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein / 1606". Carus-Verlag (in German). Retrieved 2 February 2019.

"Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein (L) / Gesänge – Woche – Gesänge zur Kommunion / Dank nach der Kommunion". mein-gotteslob.de (in German). Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein l4a.org

Gotteslobvideo (GL 216): Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein on YouTube