Inscribed sphere (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sphere tangent to every face of a polyhedron

Tetrahedron with insphere in red (also midsphere in green, circumsphere in blue)

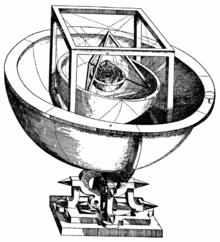

In his 1597 book Mysterium Cosmographicum, Kepler modelled of the Solar System with its then known six planets' orbits by nested platonic solids, each circumscribed and inscribed by a sphere.

In geometry, the inscribed sphere or insphere of a convex polyhedron is a sphere that is contained within the polyhedron and tangent to each of the polyhedron's faces. It is the largest sphere that is contained wholly within the polyhedron, and is dual to the dual polyhedron's circumsphere.

The radius of the sphere inscribed in a polyhedron P is called the inradius of P.

All regular polyhedra have inscribed spheres, but most irregular polyhedra do not have all facets tangent to a common sphere, although it is still possible to define the largest contained sphere for such shapes. For such cases, the notion of an insphere does not seem to have been properly defined and various interpretations of an insphere are to be found:

- The sphere tangent to all faces (if one exists).

- The sphere tangent to all face planes (if one exists).

- The sphere tangent to a given set of faces (if one exists).

- The largest sphere that can fit inside the polyhedron.

Often these spheres coincide, leading to confusion as to exactly what properties define the insphere for polyhedra where they do not coincide.

For example, the regular small stellated dodecahedron has a sphere tangent to all faces, while a larger sphere can still be fitted inside the polyhedron. Which is the insphere? Important authorities such as Coxeter or Cundy & Rollett are clear enough that the face-tangent sphere is the insphere. Again, such authorities agree that the Archimedean polyhedra (having regular faces and equivalent vertices) have no inspheres while the Archimedean dual or Catalan polyhedra do have inspheres. But many authors fail to respect such distinctions and assume other definitions for the 'inspheres' of their polyhedra.

- Circumscribed sphere

- Inscribed circle

- Midsphere

- Sphere packing

- Coxeter, H.S.M. Regular Polytopes 3rd Edn. Dover (1973).

- Cundy, H.M. and Rollett, A.P. Mathematical Models, 2nd Edn. OUP (1961).

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Insphere". MathWorld.