Isospin (original) (raw)

Quantum number related to the weak interaction

In nuclear physics and particle physics, isospin (I) is a quantum number related to the up- and down quark content of the particle. Isospin is also known as isobaric spin or isotopic spin. Isospin symmetry is a subset of the flavour symmetry seen more broadly in the interactions of baryons and mesons.

The name of the concept contains the term spin because its quantum mechanical description is mathematically similar to that of angular momentum (in particular, in the way it couples; for example, a proton–neutron pair can be coupled either in a state of total isospin 1 or in one of 0[1]). But unlike angular momentum, it is a dimensionless quantity and is not actually any type of spin.

Before the concept of quarks was introduced, particles that are affected equally by the strong force but had different charges (e.g. protons and neutrons) were considered different states of the same particle, but having isospin values related to the number of charge states.[2] A close examination of isospin symmetry ultimately led directly to the discovery and understanding of quarks and to the development of Yang–Mills theory. Isospin symmetry remains an important concept in particle physics.

To a good approximation the proton and neutron have the same mass: they can be interpreted as two states of the same particle.[2]: 141 These states have different values for an internal isospin coordinate. The mathematical properties of this coordinate are completely analogous to intrinsic spin angular momentum. The component of the operator, T ^ 3 {\displaystyle {\hat {T}}_{3}}

The internal structure of these nucleons is governed by the strong interaction, but the Hamiltonian of the strong interaction is isospin invariant. As a consequence the nuclear forces are charge independent. Properties like the stability of deuterium can be predicted based on isospin analysis.[2]: 149 However, this invariance is not exact and the quark model gives more precise results.

Relation to hypercharge

[edit]

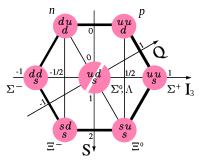

The charge operator can be expressed in terms of the projection of isospin T 3 {\displaystyle T_{3}}

Quark content and isospin

[edit]

In the modern formulation, isospin (I) is defined as a vector quantity in which up and down quarks have a value of I = 1/2, with the 3rd-component (I3) being +1/2 for up quarks, and −1/2 for down quarks, while all other quarks have I = 0. Therefore, for hadrons in general,[3] where nu and nd are the numbers of up and down quarks respectively,

I 3 = 1 2 ( n u − n d ) . {\displaystyle I_{3}={\frac {1}{2}}(n_{u}-n_{d}).}

In any combination of quarks, the 3rd component of the isospin vector (I3) could either be aligned between a pair of quarks, or face the opposite direction, giving different possible values for total isospin for any combination of quark flavours. Hadrons with the same quark content but different total isospin can be distinguished experimentally, verifying that flavour is actually a vector quantity, not a scalar (up vs down simply being a projection in the quantum mechanical z axis of flavour space).

For example, a strange quark can be combined with an up and a down quark to form a baryon, but there are two different ways the isospin values can combine – either adding (due to being flavour-aligned) or cancelling out (due to being in opposite flavour directions). The isospin-1 state (the

Σ0

) and the isospin-0 state (the

Λ0

) have different experimentally detected masses and half-lives.

Isospin and symmetry

[edit]

Isospin is regarded as a symmetry of the strong interaction under the action of the Lie group SU(2), the two states being the up flavour and down flavour. In quantum mechanics, when a Hamiltonian has a symmetry, that symmetry manifests itself through a set of states that have the same energy (the states are described as being degenerate). In simple terms, the energy operator for the strong interaction gives the same result when an up quark and an otherwise identical down quark are swapped around.

Like the case for regular spin, the isospin operator I is vector-valued: it has three components Ix, Iy, Iz, which are coordinates in the same 3-dimensional vector space where the 3 representation acts. Note that this vector space has nothing to do with the physical space, except similar mathematical formalism. Isospin is described by two quantum numbers: I – the total isospin, and I3 – an eigenvalue of the Iz projection for which flavor states are eigenstates. In other words, each I3 state specifies certain flavor state of a multiplet. The third coordinate (z), to which the "3" subscript refers, is chosen due to notational conventions that relate bases in 2 and 3 representation spaces. Namely, for the spin-1/2 case, components of I are equal to Pauli matrices divided by 2, and so Iz = 1/2 τ3, where

τ 3 = ( 1 0 0 − 1 ) . {\displaystyle \tau _{3}={\begin{pmatrix}1&0\\0&-1\end{pmatrix}}.}

While the forms of these matrices are isomorphic to those of spin, these Pauli matrices only act within the Hilbert space of isospin, not that of spin, and therefore is common to denote them with τ rather than σ to avoid confusion.

Although isospin symmetry is actually very slightly broken, SU(3) symmetry is more badly broken, due to the much higher mass of the strange quark compared to the up and down. The discovery of charm, bottomness and topness could lead to further expansions up to SU(6) flavour symmetry, which would hold if all six quarks were identical. However, the very much larger masses of the charm, bottom, and top quarks means that SU(6) flavour symmetry is very badly broken in nature (at least at low energies), and assuming this symmetry leads to qualitatively and quantitatively incorrect predictions. In modern applications, such as lattice QCD, isospin symmetry is often treated as exact for the three light quarks (uds), while the three heavy quarks (cbt) must be treated separately.

Hadron nomenclature

[edit]

Hadron nomenclature is based on isospin.[4]

- Particles of total isospin 3/2 are named Delta baryons and can be made by a combination of any three up or down quarks (but only up or down quarks).

- Particles of total isospin 1 can be made from two up quarks, two down quarks, or one of each:

- certain mesons – further differentiated by total spin into pions (total spin 0) and rho mesons (total spin 1)

- with an additional quark of higher flavour – Sigma baryons

- Particles of total isospin 1/2 can be made from:

- a single up or down quark together with an additional quark of higher flavour – strange (kaons), charm (D meson), or bottom (B meson)

- a single up or down quark together with two additional quarks of higher flavour – Xi baryon

- an up quark, a down quark, and either an up or a down quark – nucleons. Note that three identical quarks would be forbidden by the Pauli exclusion principle due to requirement of anti-symmetric wave function

- Particles of total isospin 0 can be made from

In 1932, Werner Heisenberg[5] introduced a new (unnamed) concept to explain binding of the proton and the then newly discovered neutron (symbol n). His model resembled the bonding model for molecule Hydrogen ion, H2+: a single electron was shared by two protons. Heisenberg's theory had several problems, most notable it incorrectly predicted the exceptionally strong binding energy of He+2, alpha particles. However, its equal treatment of the proton and neutron gained significance when several experimental studies showed these particles must bind almost equally.[6]: 39 In response, Eugene Wigner used Heisenberg's concept in his 1937 paper where he introduced the term "isotopic spin" to indicate how the concept is similar to spin in behavior.[7]

These considerations would also prove useful in the analysis of meson-nucleon interactions after the discovery of the pions in 1947. The three pions (

π+

,

π0

,

π−

) could be assigned to an isospin triplet with I = 1 and _I_3 = +1, 0 or −1. By assuming that isospin was conserved by nuclear interactions, the new mesons were more easily accommodated by nuclear theory.

As further particles were discovered, they were assigned into isospin multiplets according to the number of different charge states seen: 2 doublets I = 1/2 of K mesons (

K−

,

K0

), (

K+

,

K0

), a triplet I = 1 of Sigma baryons (

Σ+

,

Σ0

,

Σ−

), a singlet I = 0 Lambda baryon (

Λ0

), a quartet I = 3/2 Delta baryons (

Δ++

,

Δ+

,

Δ0

,

Δ−

), and so on.

The power of isospin symmetry and related methods comes from the observation that families of particles with similar masses tend to correspond to the invariant subspaces associated with the irreducible representations of the Lie algebra SU(2). In this context, an invariant subspace is spanned by basis vectors which correspond to particles in a family. Under the action of the Lie algebra SU(2), which generates rotations in isospin space, elements corresponding to definite particle states or superpositions of states can be rotated into each other, but can never leave the space (since the subspace is in fact invariant). This is reflective of the symmetry present. The fact that unitary matrices will commute with the Hamiltonian means that the physical quantities calculated do not change even under unitary transformation. In the case of isospin, this machinery is used to reflect the fact that the mathematics of the strong force behaves the same if a proton and neutron are swapped around (in the modern formulation, the up and down quark).

An example: Delta baryons

[edit]

For example, the particles known as the Delta baryons – baryons of spin 3/2 – were grouped together because they all have nearly the same mass (approximately 1232 MeV/_c_2) and interact in nearly the same way.

They could be treated as the same particle, with the difference in charge being due to the particle being in different states. Isospin was introduced in order to be the variable that defined this difference of state. In an analogue to spin, an isospin projection (denoted _I_3) is associated to each charged state; since there were four Deltas, four projections were needed. Like spin, isospin projections were made to vary in increments of 1. Hence, in order to have four increments of 1, an isospin value of 3/2 is required (giving the projections _I_3 = +3/2, +1/2, −1/2, −3/2). Thus, all the Deltas were said to have isospin I = 3/2, and each individual charge had different _I_3 (e.g. the

Δ++

was associated with _I_3 = +3/2).

In the isospin picture, the four Deltas and the two nucleons were thought to simply be the different states of two particles. The Delta baryons are now understood to be made of a mix of three up and down quarks – uuu (

Δ++

), uud (

Δ+

), udd (

Δ0

), and ddd (

Δ−

); the difference in charge being difference in the charges of up and down quarks (+2/3 e and −1/3 e respectively); yet, they can also be thought of as the excited states of the nucleons.

Gauged isospin symmetry

[edit]

Attempts have been made to promote isospin from a global to a local symmetry. In 1954, Chen Ning Yang and Robert Mills suggested that the notion of protons and neutrons, which are continuously rotated into each other by isospin, should be allowed to vary from point to point. To describe this, the proton and neutron direction in isospin space must be defined at every point, giving local basis for isospin. A gauge connection would then describe how to transform isospin along a path between two points.

This Yang–Mills theory describes interacting vector bosons, like the photon of electromagnetism. Unlike the photon, the SU(2) gauge theory would contain self-interacting gauge bosons. The condition of gauge invariance suggests that they have zero mass, just as in electromagnetism.

Ignoring the massless problem, as Yang and Mills did, the theory makes a firm prediction: the vector particle should couple to all particles of a given isospin universally. The coupling to the nucleon would be the same as the coupling to the kaons. The coupling to the pions would be the same as the self-coupling of the vector bosons to themselves.

When Yang and Mills proposed the theory, there was no candidate vector boson. J. J. Sakurai in 1960 predicted that there should be a massive vector boson which is coupled to isospin, and predicted that it would show universal couplings. The rho mesons were discovered a short time later, and were quickly identified as Sakurai's vector bosons. The couplings of the rho to the nucleons and to each other were verified to be universal, as best as experiment could measure. The fact that the diagonal isospin current contains part of the electromagnetic current led to the prediction of rho-photon mixing and the concept of vector meson dominance, ideas which led to successful theoretical pictures of GeV-scale photon-nucleus scattering.

The introduction of quarks

[edit]

Combinations of three u, d or s-quarks forming baryons with spin-3⁄2 form the baryon decuplet.

Combinations of three u, d or s-quarks forming baryons with spin-1⁄2 form the baryon octet

The discovery and subsequent analysis of additional particles, both mesons and baryons, made it clear that the concept of isospin symmetry could be broadened to an even larger symmetry group, now called flavor symmetry. Once the kaons and their property of strangeness became better understood, it started to become clear that these, too, seemed to be a part of an enlarged symmetry that contained isospin as a subgroup. The larger symmetry was named the Eightfold Way by Murray Gell-Mann, and was promptly recognized to correspond to the adjoint representation of SU(3). To better understand the origin of this symmetry, Gell-Mann proposed the existence of up, down and strange quarks which would belong to the fundamental representation of the SU(3) flavor symmetry.

In the quark model, the isospin projection (_I_3) followed from the up and down quark content of particles; uud for the proton and udd for the neutron. Technically, the nucleon doublet states are seen to be linear combinations of products of 3-particle isospin doublet states and spin doublet states. That is, the (spin-up) proton wave function, in terms of quark-flavour eigenstates, is described by[2]

| p ↑ ⟩ = 1 3 2 ( | d u u ⟩ | u d u ⟩ | u u d ⟩ ) ( 2 − 1 − 1 − 1 2 − 1 − 1 − 1 2 ) ( | ↓↑↑ ⟩ | ↑↓↑ ⟩ | ↑↑↓ ⟩ ) {\displaystyle \vert \mathrm {p} \uparrow \rangle ={\frac {1}{3{\sqrt {2}}}}\left({\begin{array}{ccc}\vert \mathrm {duu} \rangle &\vert \mathrm {udu} \rangle &\vert \mathrm {uud} \rangle \end{array}}\right)\left({\begin{array}{ccc}2&-1&-1\\-1&2&-1\\-1&-1&2\end{array}}\right)\left({\begin{array}{c}\left\vert \downarrow \uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle \\\left\vert \uparrow \downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle \\\left\vert \uparrow \uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle \end{array}}\right)}

and the (spin-up) neutron by

| n ↑ ⟩ = 1 3 2 ( | u d d ⟩ | d u d ⟩ | d d u ⟩ ) ( 2 − 1 − 1 − 1 2 − 1 − 1 − 1 2 ) ( | ↓↑↑ ⟩ | ↑↓↑ ⟩ | ↑↑↓ ⟩ ) . {\displaystyle \vert \mathrm {n} \uparrow \rangle ={\frac {1}{3{\sqrt {2}}}}\left({\begin{array}{ccc}\vert \mathrm {udd} \rangle &\vert \mathrm {dud} \rangle &\vert \mathrm {ddu} \rangle \end{array}}\right)\left({\begin{array}{ccc}2&-1&-1\\-1&2&-1\\-1&-1&2\end{array}}\right)\left({\begin{array}{c}\left\vert \downarrow \uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle \\\left\vert \uparrow \downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle \\\left\vert \uparrow \uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle \end{array}}\right).}

Here, | u ⟩ {\displaystyle \mathrm {\vert u\rangle } }

Similarly, the isospin symmetry of the pions are given by:

| π + ⟩ = | u d ¯ ⟩ | π 0 ⟩ = 1 2 ( | u u ¯ ⟩ − | d d ¯ ⟩ ) | π − ⟩ = − | d u ¯ ⟩ . {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vert \pi ^{+}\rangle &=\vert \mathrm {u{\overline {d}}} \rangle \\\vert \pi ^{0}\rangle &={\tfrac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left(\vert \mathrm {u{\overline {u}}} \rangle -\vert \mathrm {d{\overline {d}}} \rangle \right)\\\vert \pi ^{-}\rangle &=-\vert \mathrm {d{\overline {u}}} \rangle .\end{aligned}}}

Although the discovery of the quarks led to reinterpretation of mesons as a vector bound state of a quark and an antiquark, it is sometimes still useful to think of them as being the gauge bosons of a hidden local symmetry.[8]

In 1961 Sheldon Glashow proposed that as relation similar to the Gell-Mann–Nishijima formula for charge to isospin would also apply to the weak interaction:[9][10]: 152 Q = T 3 + 1 2 Y w . {\displaystyle Q=T_{3}+{\frac {1}{2}}Y_{w}.}

- ^ Povh, Bogdan; Klaus, Rith; Scholz, Christoph; Zetsche, Frank (2008) [1993]. "Chapter 2". Particles and Nuclei. Springer. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-540-79367-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Greiner, W.; Müller, B. (1994). Quantum Mechanics: Symmetries (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 279. ISBN 978-3540580805.

- ^ Pal, Palash Baran (29 July 2014). An Introductory Course of Particle Physics. CRC Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-4822-1698-1.

- ^ Amsler, C.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: Naming scheme for hadrons" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1): 1–6. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. hdl:1854/LU-685594. S2CID 227119789.

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 77 (1–2): 1–11. Bibcode:1932ZPhy...77....1H. doi:10.1007/BF01342433. S2CID 186218053.

- ^ Brown, L.M. (1988). "Remarks on the history of isospin". In Winter, Klaus; Telegdi, Valentine L. (eds.). Festi-Val: Festschrift for Val Telegdi; essays in physics in honour of his 65th birthday; [a symposium ... was held at CERN, Geneva on 6 July 1987]. Amsterdam: North-Holland Physics Publ. ISBN 978-0-444-87099-5.

- ^ Wigner, E. (1937). "On the Consequences of the Symmetry of the Nuclear Hamiltonian on the Spectroscopy of Nuclei". Physical Review. 51 (2): 106–119. Bibcode:1937PhRv...51..106W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.51.106.

- ^ Bando, M.; Kugo, T.; Uehara, S.; Yamawaki, K.; Yanagida, T. (1985). "Is the ρ Meson a Dynamical Gauge Boson of Hidden Local Symmetry?". Physical Review Letters. 54 (12): 1215–1218. Bibcode:1985PhRvL..54.1215B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.1215. PMID 10030967.

- ^ Glashow, Sheldon L. (1961-02-01). "Partial-symmetries of weak interactions". Nuclear Physics. 22 (4): 579–588. Bibcode:1961NucPh..22..579G. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(61)90469-2. ISSN 0029-5582.

- ^ Greiner, Walter; Müller, Berndt; Greiner, Walter (1996). Gauge theory of weak interactions (2 ed.). Berlin Heidelberg New York Barcelona Budapest Hong Kong London Milan Paris Santa Clara Singapore Tokyo: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-60227-9.

- ^ Robson, B. A. (Oct 2004). "Relation Between Strong and Weak Isospin". International Journal of Modern Physics E. 13 (5): 999–1018. Bibcode:2004IJMPE..13..999R. doi:10.1142/S0218301304002521. ISSN 0218-3013.

- Itzykson, C.; Zuber, J.-B. (1980). Quantum Field Theory. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-032071-0.

- Griffiths, D. (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-60386-3.

- Chan–Paton factor

- i8 i**Nuclear Structure and Decay Data - IAEA ** Nuclides' Isospin