Jan Švankmajer (original) (raw)

Czech filmmaker (born 1934)

| Doctor honoris causaJan Švankmajer | |

|---|---|

Švankmajer in 2024 Švankmajer in 2024 |

|

| Born | (1934-09-04) 4 September 1934 (age 90)Prague, Czechoslovakia |

| Education | Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague |

| Known for | Filmmaker in animation, puppetry and live-action; writer, playwright and surrealist |

| Style | informel, surrealism, tactilism, art brut |

| Spouse | Eva Švankmajerová |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Czech Lion Awards - Unique Contribution to Czech Film (1994), Best Design (Faust, 1994, Little Otik, 2001, Surviving Life, 2010), Best Stage Design (Insects), 2018), Grand Prix and International Critics Award, Annecy International Animation Film Festival, Golden Bear, Berlinale (Dimensions of Dialogue, 1983), Prix special for lifelong achievement, International Animated Film Association (1990), FITES Award for Lifetime Contribution to the Development of Audiovisual Culture (2008), Freedom Award for Lifetime Achievement (Andrzej Wajda Award), Berlinale (2001) |

Jan Švankmajer (born 4 September 1934) is a Czech retired[1] film director, animator, writer, playwright and artist. He draws and makes free graphics, collage, ceramics, tactile objects and assemblages.[2] In the early 1960s, he explored informel, which later became an important part of the visual form of his animated films.[3] He is a leading representative of late Czech surrealism. In his film work, he created an unmistakable and quite specific style, determined primarily by a compulsively unorthodox combination of externally disparate elements. The anti-artistic nature of this process, based on collage or assemblage, functions as a meaning-making factor.[4] The author himself claims that the intersubjective communication between him and the viewer works only through evoked associations, and his films fulfil their subversive mission only when, even in the most fantastic moments, they look like a record of reality.[5] Some of the works he created together with his wife Eva Švankmajerová.[6]

Jan Švankmajer was born in Prague on 4 September 1934.[7] His father was a window dresser and his mother a seamstress. His childhood was profoundly influenced by a home puppet theatre,[8] which he received as an eight-year-old boy for Christmas and gradually made his own puppets and painted the sets. Švankmajer admits that since then, puppets have been firmly embedded in his mental morphology, and he always resorts to them when he feels threatened by the reality of the outside world.[9] He sees them not only in the context of theatre, but as a ritual symbol used in magic. The ludic principle on which Švankmajer's work is based has its roots in his childhood.[10]

In 1950-1954 he graduated in scenography at the Higher School of Art Industry in Prague, under Prof. Richard Lander, where he designed and made puppets and sets.[11] His classmates were Aleš Veselý and photographer Jan Svoboda. He then studied directing and stage design at the Department of Puppets at the Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (1954-1958), where Lander moved to as a teacher at that time. Even during the most rigid Stalinist regime, the atmosphere at the school was liberal and forbidden books on French modern art circulated among the students, brought by the painting teacher Karel Tondl.[12] His classmate and friend was the later film director Juraj Herz. At the end of his studies, he took part in a sightseeing trip to Poland, where he saw reproductions of Paul Klee's works for the first time.

During his studies, he staged the folk puppeteers' play Don Šajn (Don Juan) at the then Small Theatre D 34 (1957-1958), led by Emil František Burian. In addition to D 34 theatre, he attended the Liberated Theatre and became acquainted with the works of the Russian avant-garde (Mejerhold, Eisenstein).[13] In his graduation performance (C. Gozzi, The King Stag) he used a combination of puppets with live actors in masks. Soon after graduation in 1958, he participated as a puppeteer in Radok's short film Johannes Doctor Faust, inspired by folk puppeteers. During the filming he met composer Zdeněk Liška, cinematographer Svatopluk Malý and designer Vlastimil Beneš. He briefly worked as a director and designer at the State Puppet Theatre in Liberec (the predecessor of Studio Ypsilon).[14] In 1958-1960, he completed his compulsory military service in Mariánské Lázně, where he drew and painted intensively (Men, pen, watercolour on pressed paper, 1959).

After returning from the army in 1960, he founded the group Theatre of Masks, which belonged to the Semafor theatre. During the preparation of the first production of Starched Heads, he met Eva Dvořáková, whom he later married. Other productions of the Theatre of Masks were Johannes Doctor Faust, The Collector of Shadows, Circus Sucric. In 1962 he exhibited his drawings in the corridor of the Semafor and Vlastimil Beneš and Zbyněk Sekal, who visited the exhibition, invited him to join the Máj 57 group. He took part in the fourth exhibition of the Máj group in Poděbrady (1961), which was banned after three days, and then exhibited with the members of the group until the end of the 1960s.[15]

The avant-garde Theatre of Masks did not fit Semafor's profile as a musical stage. In 1962, Jiří Suchý closed it down, but Emil Radok facilitated the engagement of the entire group of the Theatre of Masks in Magician's Lantern. In this year Jan Švankmajer made his first trip to Paris. In 1963 his daughter Veronika was born. After leaving Semafor, he worked until 1964 as director and head of the Black light theatre company at Magician's Lantern. He directed two performances for the Variations programmes and later also externally for the Magic Circus, The Lost Fairy Tale. At the same time, together with Emil Radok, he was making up scripts for future films.[16]

In 1964 he made his first short film, The Last Trick, based on the principles of black theatre. It features elements typical of all his subsequent work, such as the dynamic use of montage and the juxtaposition of live actors with animated objects. The film was successful abroad, and in the following years Švankmajer was given the opportunity to make short films combining puppetry, animation and elements of live action. In his early films, composed as short grotesques, black humour and peculiarly interpreted poetics of folk puppet plays prevail.[17] In the second film from 1964, Johann Sebastian Bach: Fantasia in G minor, the visual component is a kind of mannerist informel with a recognizable influence of surrealist photographs by Emila Medková.[18] In 1965, he made the film Spiel mit steinen (Playing with Stones) practically alone, with the help of Eva Švankmajerová and cinematographer Petr Puluj in Austria. He tried out various animation techniques, later used, for example, in the film Dimensions of Dialogue. For the Expo 67 competition in Montreal, he made a short film Man and Technique[19] and participated in the film Digits by Pavel Procházka. In 1968 the Švankmajer family moved to the house No. 97/5 in Nový svět (Hradčany).[20]

In 1968, he signed manifesto The Two Thousand Words. After the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, the whole family emigrated to Austria at the instigation of Eva Švankmajerová. Here he made his second film in an Austrian production in the studio of Peter Puluj (Picknick mit Weissmann). In 1968, he received the Max Ernst Prize at the Oberhausen Film Festival for his film Historia naturae. In 1969 the family decided to return to Czechoslovakia. In 1970 he met Vratislav Effenberger and together with Eva Švankmajerová they became members of the Surrealist Group in Czechoslovakia.[21] Between 1971 and 1989 they contributed to samizdat edited anthologies Le-La and catalogues (Open Game, Sphere of Dream, Transformations of Humour, Imaginative Spaces, Opposite of the Mirror).[22] After 1989 to the first and only issue of the anthology Gambra and then to the magazine Analogon.[23]

During the short period up to 1970 Švankmajer still managed to make the "Kafkaesque" allegorical short films The Garden, The Apartment and Silent Week in the House, the morbid Ossuary and the "puppet" film Don Šajn (1970), in which marionettes are replaced by live actors who have wires and guide strings attached to their papier-mâché heads, symbolizing the theme of human manipulation and the limitations of individual freedom.[24] After the advent of the normalization regime, Švankmajer's creative work was hampered by censorship and his short films The Garden and The Apartment ended up in the vault. In 1972, as a volunteer, he underwent an experiment with intravenous administration of LSD at the Military Hospital in Prague. The experiment had a devastating effect on him, with anxiety states[25] that he still recalls in his work 30 years later.[26][27]

In 1972-1979 he was banned from filming because he refused to make compromise on the post-production of his film The Castle of Otranto, based on a gothic novel by H. Walpole.[28] In 1973-1980 he worked as a production designer and film trick maker at Barrandov Studios.[29] In 1975 his son Václav was born. In the 1970s, Jan Švankmajer worked as a stage designer at the Theatre on the Balustrade, the Večerní Brno Theatre, and especially at The Drama Club, where he was invited by Jaroslav Vostrý (Candide, The Educator, Crackle on the Lagoon, The Golden Carriage). Eva Švankmajerová participated in the performances as a costume designer and stage designer. Since 1976 he and his wife Eva have been creating ceramics under the joint pseudonym Kostelec.[30]

As a trick designer and production designer in Barrandov Studios, he collaborated on the films of Oldřich Lipský (Dinner for Adele, 1977, The Mysterious Castle in the Carpathians, 1981) and Juraj Herz (The Ninth Heart, 1978, Upír z Feratu (The Vampire of Ferat), 1981).[22] At the end of his persecution, he filmed two of Poe's short stories, The Fall of the House of Usher and The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope, using themes from the work of Villiers de l'Isle Adam. In 1981 Jan and Eva Švankmajer bought a dilapidated castle in Horní Stankov,[31] where they wanted to set up a ceramics workshop. Since then, they have been gradually reconstructing the castle and transforming it into a surreal Cabinet of Curiosities, consisting of their own artefacts and various collections of art and natural objects. Švankmajer's collecting is a form of self-therapy,[32] and in addition to found or purchased objects, it includes art from the natural peoples of Africa and Polynesia.

A retrospective of Švankmajer's films from the 1960s attracted international attention at the 1983 FIFA International Film Festival in Annency. He received the Grand Prix and the International Critics' Prize for the Dimensions of Dialogue and the Golden Bear at the Berlinale the same year. Terry Gilliam ranks this film among the ten best animated films of all time.[33] At home, Švankmajer became a victim of the score settling between the management of Czechoslovak Television and Short Film Prague, and Dimensions of Dialogue was shown to the ideological committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia's Central Committee as a deterrent. After that, he was again unable to work at Short Film studios and went to Bratislava, where he made the film Do pivnice (Into the cellar) in 1983. In the same year, he published his book Hmat a imaginace (Touch and Imagination) in five copies as a samizdat, summarising the results of his tactile experiments since 1974. He managed to secure money abroad for his project Alice, but the studios of Short Film and Barandov were not interested in filming. At that time, the state had a monopoly on all film production. So he turned to Jaromír Kallista, whom he knew as the producer of Magician's Lantern, and asked him if he would direct the project with him as an independent film.

He presented his first feature-length film Alice, which was made during 1987 almost exclusively in a Swiss production (Condor Films), in 1988. The work was a worldwide success and won the Best Animated Feature Award at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival (JICA). At the same time, The Dimensions of Dialogue won the Grand Prize for the best film in the festival history.[34] In 1990, he made the political grotesque agitprop film The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia and in 1992 the short work Food, in which he comes to terms with his gastronomic obsessions.

In the following years he devoted himself exclusively to directing feature films. The house at 27 Nerudova Street (Malá Strana), where Švankmajer had his film studio, was privatised and he had to leave it in the middle of the filming of The Faust. In 1991, together with Jaromír Kallista, he bought a former cinema in the village of Knovíz and founded his own film studio ATHANOR,[35] where he made next films. At the prestigious Cardiff Animation Film Festival[36] (1992) he was awarded the First IFA Prize and the BBC presented a show of his animated films over two nights.[37][38][39]

In 1994, Švankmajer's second feature film The Faust was premiered, starring Petr Čepek in the dual roles of Faust and Mephisto. Faust, a random man in the crowd, is manipulated by the entire plot and become accustomed to the role of Faust, which he plays to the bitter end. The film is an attempt at actual interpretation of the Faust myth and asks the question of what a man is allowed to know without destroying himself.[40] This relationship is highly ambivalent and therefore provokes contradictory interpretations.[41] The filming was accompanied by a series of tragic deaths and unexplained circumstances, and Petr Čepek himself completed the film at a time when he was already seriously ill.[42] For this performance Čepek was awarded the Czech Lion in memoriam. The film was selected for the prestigious out-of-competition screening at the Cannes Film Festival. In 1994, Short Film Prague released a set of 26 Švankmajer's films on cassettes.[43] In Great Britain, Jan Švankmajer received the Lifetime Achievement Award.

In 1996 Švankmajer made Conspirators of Pleasure, a black comedy about people who follow the principle of pleasure and perform harmless imaginative perversions and rituals. He contrasts their personal freedom with the moderating and repressive role of society, education or school. The film is a sarcastic satire on the contemporary world full of sexual perversions and erotic fetishes. Švankmajer has made the most of his many years of artistic experiments on the subject of tactilism. He concluded the film with the words: I believe that black and objective humour, mystification and the cynicism of fantasy are more adequate means of expressing the decadence of the times than the hypocritical, but popular "smell of humanity" in Czech films.

The following film Little Otik (2000) won the Czech Lion for Best Film and Best Art Direction (together with Eva Švankmajerová). In 2003 FAMU awarded Jan Švankmajer the title of Doctor honoris causa.[44][45]

During 2004, Eva and Jan Švankmajer had a retrospective exhibition Memory of Animation - Animation of Memory in Plzeň and an exhibition called Food in the Prague Castle Riding Hall. Both were a great success with the general public and were considered by critics to be the artistic event of the year.[46] A retrospective of 30 of his films was shown as part of the Plzeň Film Festival on the occasion of the author's 70th birthday.[47]

On 17 November 2005, the film Lunacy premiered, which is conceived as a philosophical horror film inspired by the personality of the Marquis de Sade and the short stories of Edgar Allan Poe. Eva Švankmajerová, who died shortly before the premiere, was awarded the Czech Lion in memoriam for the artistic concept and poster for this film. Their daughter Veronika Hrubá also collaborated on the film. Student Jurry at the Plzeň Film Festival awarded Lunacy as the Best Feature Film. At the 2009 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, Jan Švankmajer received the Crystal Globe for Outstanding Contribution to World Cinema.[48]

His last feature film so far, Insects, based on Švankmajer's 1971 short story[49] (inspired by the play Pictures from the Insects' Life of the Čapek brothers, with a reference to Kafka's The Metamorphosis), was screened at film festivals in 2018 and had its UK premiere at the Tate Modern.[50] The Rotterdam festival screened Insects in the section Signatures dedicated to great authors and filmmakers.[51] Jan Švankmajer has established an exclusive position in the history of cinema and is recognized as one of the few contemporary Czech filmmakers abroad.[52] By 2018, he had received 36 awards and 17 nominations for his films worldwide, including the 2018 Raymond Roussel Medal for Lifetime Achievement in Film, awarded by the Raymond Roussel Society in Barcelona.[53]

Since 1970, Jan Švankmajer has participated in the activities of the Surrealist Group in Czechoslovakia and is the chairman of the editorial board of the Analogon magazine (104 issues until 2024),[54] to which he also contributes. In 1990, he participated in the collective exhibition of the Surrealist Group The Third Ark in Prague's Mánes. Since 1991 he has been a member of Mánes Union of Fine Arts.[2] He animates his films alone (The Fall of the House of Usher) or in collaboration with top animators such as Vlasta Pospíšilová and Bedřich Glaser. In his feature films, he has collaborated with friends from his time at The Drama Club (Jiří Hálek, Petr Čepek) and other proven actors (Jan Kraus, Jiří Lábus, Pavel Nový, Jan Tříska, Martin Huba, Pavel Liška, Václav Helšus, Anna Geislerová, Veronika Žilková, Klára Issová, etc.).

Jan Švankmajer uncompromisingly defends his personal freedom and rejects any official awards granted by state authorities. In 1989 he rejected the Merited Artist award, in the 1990s the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and in 2011 the award proposed by Václav Havel. He considers the state as a source of organized violence and means of oppression and manipulation.[55]

Eva Švankmajerová participated in some of the films as a stage and production designer. Their son Václav Švankmajer is also a successful filmmaker,[56] including The Torchbearer. He contributed to the artwork for the film Insects (2018). Švankmajer's daughter Veronika Hrubá collaborated as a costume designer on the films Lunacy (Czech Lion Award), Surviving Life, and Insects.[57]

- 1964 Awards at film festivals in Bergamo, Mannheim, Tours, Buenos Aires

- 1965 Third Prize for short film Cannes Film Festival - (J.S. Bach - Fantasia G-moll)

- 1966 Josef von Sternberg Award, Mannheim-Heidelberg International Filmfestival - (Rakvičkárna (Punch and Judy)

- 1967 Festival of short films Karlovy Vary, Trilobit Award

- 1968 Max Ernst Prize, International Short Film Festival Oberhausen - (Historia naturae)

- 1983 Grand Prix, International Critic´s Prize, Annecy International Animation Film Festival, Golden Bear, Berlinale - (Dimensions of Dialogue)

- 1984 Jury Prize, Montreal World Film Festival - (The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope)

- 1985 Critic´s Prize, Fantasporto - (The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope)

- 1989 Grand Prix, Cinanima (International Animated Film Festival, Portugal) - (Darkness/Light/Darkness), Feature Film Award, Annecy International Animation Film Festival - (Alice)

- 1990 Honorable mention for short film, Berlinale - (Darkness/Light/Darkness)

- 1990 Prix special for previous works (best film of 30 years of presentations of animated films), ASIFA[6]

- 1994 Special jury prize, nomination: Crystal Globe (Karlovy Vary International Film Festival) - (Faust)

- 1994 Czech Lion Award for outstanding contribution to Czech cinema, nomination: Best director, Best script - (Faust)

- 1995 Lifetime Achievement Award, Great Britain,[6] Best speciaal effects, Fantasporto, Annual Czech Film Critics Award Kristián - (Faust)

- 1996 Youth Jury Award, Locarno Film Festival[6]

- 1997 Golden Gate Persistence of Vision Award, San Francisco International Film Festival[58]

- 2001 Czech Lion Award, KVIFF: Best design, nomination: Best director, Best script - (Little Otik)

- 2001 Andrzej Wajda Freedom Prize, American Cinema Foundation[59]

- 2002 Annual Czech Film Critics Award Kristián - (Little Otik)

- 2006 Award for Lifetime Contribution to the Development of Audiovisual Culture FITES[6]

- 2006 Award for the best artistic achievement, Sun in a Net Award, Slovak FTA - (Lunacy)

- 2009 Crystal Globe (Karlovy Vary International Film Festival) For outstanding artistic contribution to world cinema

- 2010 Czech Lion Award - Best Artwork, Czech Film Critics' Award - nomination: Best director, Best script - (Surviving Life)

- 2010 Award for lifetime contribution to cinematography, 5th European Film Festival in Segovia, Spain[60]

- 2012 Best Artwork, Sun in a Net Award, Slovak FTA - (Surviving Life)

- 2014 Award of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), Karlovy Vary[61]

- 2018 Czech Lion Award - Best film script - (Insects), nomination: Best director - (Insects)

- 2018 Czech Film Critics' Award for best audiovisual achievement - (Insects)

- 2018 Medal of Raymond Roussel for Lifetime Achievement in Film, Barcelona

- 2019 Best stage design, Sun in a Net Award, Slovak FTA - (Insects)

- 2020 Czech Lion Award nomination: Best documentary (Alchymická pec)[62][63]

Švankmajer's hard-to-classify artistic style developed in the 1960s in parallel with his work in the theatre and animated films. Jan Švankmajer's early drawings were inspired by Paul Klee. Around 1960, he briefly dealt with structural abstraction,[64] but soon returned to figuration and from the late 1960s onwards embraced surrealism. His objects from the early 1960s can be classified as informel only formally, on the basis of similarities in expressivity and surface structure, but in reality they were real objects, subjected to a process of transformation as "accelerated aging" or ornamentation.[65] However, his preoccupation with informel runs through his entire film oeuvre, as macro details of scratched walls and age-marked objects, or the sudden transformation of things into undifferentiated matter, form a significant part of the visual form of his animated films.[3] His Springs objects - usually shoes, mineralized in Karlovy Vary spring water - date from 2009.[66]

He became a member of the Surrealist Group, which was formed around Vratislav Effenberger, at a time when the group was going through a crisis. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, the ban on publishing was reinstated, many people went into exile and others resigned from the group. At the same time, the Surrealist movement in France disintegrated. Jan and Eva Švankmajer had a significant influence on the revival of the activities of the Surrealist Group. The group's interest in all kinds of imaginative experiments was the basis for the creation of collective anthologies devoted to the themes of interpretation, analogy, eroticism and tactilism. Švankmajer considers imagination to be a gift that humanizes man.[67]

As artist, he was later influenced by the Surrealists Max Ernst, R. Magritte, G. Chirico, of the older ones Hieronymus Bosch and especially the Mannerism of Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Švankmajer's films Playing with Stones, Historia naturae and Dimensions of Dialogue have a direct connection with the principles of Arcimboldo's Mannerist painting. His collections of curiosities (similar to Rudolf II's kunstkomora), folk puppetry, naive folk art, African and Polynesian masks and fetishes, and art brut are strong and lasting inspirations.

He is interested in the authenticity of folk puppetry and the magic associated with puppets, rather than puppets as mere artistic devices or props for animation. The puppet and the thread or guide wire, as an analogy of man's destiny and his connection to something above him that determines his fate, are known from various religions and myths. It is a space for the realization of the "impossible", incompatible with good education, for the realization of even seemingly incredible dreams. The child-puppeteer is thus in fact a shaman, a god and a creator.[68]

He cites the French Poète maudit, German Romanticism (Novalis, E. T. A. Hoffmann), and the Surrealists (A. Breton, K. Teige, B. Péret, V. Effenberger) as major literary sources. The literary inspiration for Švankmajer's films were the works of Lewis Caroll, E. A. Poe, Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam or Marquis de Sade. His interpretation of other authors' literary works is ultimately a subjective account that preserves only the terrors, dreams, and infantilism of the world he shares with them.[69]

In Švankmajer´s film work, his sense of the concrete irrationality of plots corresponds to some of the types of aggressive cinematic civilism that was applied in the works of the directors of the Czechoslovak "New Wave" (Miloš Forman, Pavel Juráček). His work shares a certain "oppositional" attitude with the films of the Czechoslovak New Wave of the 1960s, but otherwise escapes any classification.[70] Among world theatre directors and filmmakers, he was inspired by the Russian avant-garde theatre artists V. Meyerhold, A. Tairov and Bauhaus artist O. Schlemmer, by filmmakers S. Eisenstein and D. Vertov. He described films Un Chien Andalou, L'Age d'Or by Buñuel and Dalí, Amarcord, Roma (1972 film) by F. Fellini and, among the works close to animation, the films of Méliès and David Bowers as a defining cinematic experience. Of contemporary directors, he is close to David Lynch or the Quay brothers.[3]

Švankmajer makes films only when they are finished in his imagination, but during the shooting process he does not stick to the script, he looks for new sources of inspiration and tries to reach an acceptable compromise with the original intention. He himself states that filmmaking is a kind of self-therapy, and in his works he repeatedly comes to terms with his idiosyncrasies, anxieties and obsessions that originated in his childhood.[71] His preference for "decadent genres" such as folk puppets and sets, fair-ground mechanical targets, and black novels is at the root of his anti-aesthetic attitude towards filmmaking. Not only his films, but also his collages, prints, ceramics and three-dimensional objects are based on his infantile worldview, which took the form of a puppet stage with symmetrically cut sets and figures hanging on strings.[72] The alchemical and kabbalistic history of Prague is an undoubted inspiration for him, and his work builds on these sources and combines it with surrealism. Surrealism and Mannerism, which are anchored in the duality of opposites - rationalism with the irrational, sensualism with spiritualism, tradition with innovation, convention with revolt - create the necessary tension for creative activity.[73] In his view, Surrealism represents a contemporary form of Romanticism that restores art to its magical dignity.

Švankmajer strives to make his films, even in their most fantastic moments, look like records of reality. As a filmmaker, he is particularly renowned for his ability to animate any material. He sees film animation not as a technique, but as a magical means capable of animating inanimate matter and thus realising an original infantile desire.[74][75] In his conception, animation is a transformation or transmutation of matter - from an object to its parts or essence and vice versa, and is close to alchemy.[73] As a hermeticist, he believes that objects touched by people in moments of heightened sensibility have an inner life of their own and somehow preserve the contents of the subconscious.[71] In The Fall of the House of Usher, he replaced people with objects that became vehicles for the plot and the emotions of the acting characters and the atmosphere of the story.

According to Effenberger, the secret of Švankmajer's imaginative humour lies in the fact that when he juxtaposes lyrical pathos and raw reality, the rawness fades along with the pathos and lyrical reality becomes what it is in the eyes of a child or a poet.[17] In the alternation of genres, the cementing thread in his films is the dream logic, where apparent contingencies take on the form of inescapable fatality and guide the viewer smoothly through the story - the dream. There are no logical transitions between dream and reality, only the physical act of opening and closing the eyelids.[76]

Švankmajer's films are subversive and do not conform to any taboos, conventions or prescriptions of reason. They are a rebellion against the consumerist world, a radical revolution, a liberation from rigid reality and a return to the world of free play.[77] He sees destruction as a creative way of challenging rationality, but his conception of surrealism is exclusive and autonomous.[73] According to Švankmajer, surrealism is a realism that seeks the reality beneath the surface of things and phenomena. What is above reality, meets with hermeticism and psychoanalysis.[78] The author maintains absolute freedom and does not calculate with the taste of the audience - he himself says that he is indifferent whether five or five million viewers come to see his film.[79] His work has also influenced several foreign filmmakers, such as Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam, the Quay brothers, and Henry Selick.[80]

...the theme of freedom, the only theme for which it is still worth picking up a pen, brush or camera...[81]

...it is not worth striving for less than absolute freedom. Society will truncate it beyond recognition in the process anyway. If you start lower than at absolute freedom, you will have no freedom at the end.[82]

...the creative act gives meaning and rebellion (revolt) dignity to life. ibid. p. 362

...I think that without revolt a normal, decent person cannot live. There is no society that is so ideal that one does not have to revolt against it...[83]

JŠ a JŠ on his retrospective 2012, Prague City Gallery

- The Last Trick (1964), color 11;30 min., KF Prague[84]

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Fantasia in G minor (1965), B&W 9;30 min., KF Prague, Jury Prize at Cannes Film Festival[85]

- A Game with Stones (Spiel mit steinen, 1965), color 8 min., Studio A, Linz[86]

- Rakvičkárna (Punch and Judy, 1966), color 10 min., KF Prague, Jiří Trnka Studio[87]

- Et cetera (1966) color 7;15 min., KF Prague, Jiří Trnka Studio[88]

- Historia naturae (1967), color 9 min., KF Prague, Max Ernst Prize, FF Oberhausen[89]

- The Garden (1968), B&W 19 min., KF Prague[90]

- Picnic with Weissmann (1968), color 13 min., Studio A, Linz[91]

- The Flat (1968), B&W 12;30 min., KF Prague[92]

- A Quiet Week in the House (1969), color 19 min., KF Prague, Jiří Trnka Studio[93]

- The Ossuary (1970), B&W 10 min., KF Prague[94]

- Don Juan (1970), color 31 min., KF Praha[95]

- Jabberwocky (1971), color 13 min., KF Prague for Western Wood Studio, USA[96]

- Leonardo's Diary (1972), color 11 min., KF Praha, Jiří Trnka Studio, Corona Cinematografica Roma[97]

- Castle of Otranto (1977), color 17 min., KF Prague, Jiri Trnka Studio[98]

- The Fall of the House of Usher (film, 1980) (1980), B&W 15 min., KF Prague, Jiri Trnka Studio[99]

- Dimensions of Dialogue (1982), color 11;30 min., KF Prague, Jiri Trnka Studio[100]

- Do pivnice (Into the Cellar) (1982), color 15 min., SFT Bratislava[101]

- The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope (1983), b&w 15 min., KF Praha, Studio Jiří Trnka, collaboration on production design by Eva Švankmajerová[102]

- Manly Games (1988), color 12 min., KF Prague, Jiří Trnka Studio[103]

- Another Kind of Love (1988), color 3;33 min., Virgin Records, Nomad Films, Koninck International[104]

- Tma / Světlo / Tma (Dark / Light/ Dark (1989), color 8 min., KF Praha, Jiri Trnka Studio[105]

- Meat Love (1989), color 1 min., MTV USA, Nomad Films, Koninck International[106]

- Flora (1989), color 0;20 min., MTV USA[107]

- Self Portrait (1989), color 1 min., Canada, Czech Republic, Japan, USA[108]

- The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia (1990), color 10 min., J. Kallista and Jan Švankmajer for BBC, Nomad Films[109]

- Food (1992), color 17 min., J. Kallista and Jan Švankmajer for Channel 4, Heart of Europe Prague, Koninck International[110]

- Something from Alice (1988), color 84 min., Condor Film Zürich, Hessischer Rundfunk, Channel 4, Eva Švankmajerová collaborated on the production design

- Conspirators of Pleasure (1996), color 78 min., Athanor s.r.o, co-production DelFilm, Koninck Int., costumes Eva Švankmajerová

- Faust (1994), color 95 min., Athanor s.r.o., co-production Heart o Europe Prague, Lumen Films, BBC Bristol, Koninck Int., Pandora Films, co-production Eva Švankmajerová

- Little Otik (2000), color 125 min., Athanor s.r.o., co-production UK, received three Czech Lions in the categories Best Film, Art Design and Poster (2001), costumes Eva Švankmajerová

- Lunacy (2005), color 118 min., costumes Eva Švankmajerová, Czech Oscar nomination[111]

- Surviving Life (2010), color 105 min, world premiere at Venice Film Festival).[112]

- Insects (2018), color 98 min., world premiere at International Film Festival Rotterdam.[113][114][115]

Collaboration on films

[edit]

- 1958 Johannes Dr. Faust (directed by Emil Radok), puppet actor

- 1965 Digits (directed by Pavel Procházka), production designer

Props and animation design

[edit]

- 1977 Dinner for Adele, director Oldřich Lipský, art and animation by Jan Švankmajer

- 1978 The Ninth Heart, director Juraj Herz, art collaboration and subtitles Jan Švankmajer, Eva Švankmajerová

- 1981 Upír z Feratu (The Vampire of Ferat), director Juraj Herz, original car engine design Jan Švankmajer

- 1981 The Mysterious Castle in the Carpathians, director Oldřich Lipský, art by Švankmajer, animation by Bedřich Glaser

- 1983 Návštěvníci (TV series), director Jindřich Polák, art by Jan Švankmajer, animation by Bedřich Glaser

- 1983 Three Veterans, director Oldřich Lipský, art by Jan Švankmajer, animation Bedřich Glaser

Filmography overviews + DVD

[edit]

- Jan Svankmajer: The Ossuary and Other Tales (USA, Canada, 2013), DVD includes The Last Trick, Don Juan, The Garden, Historia Naturae, Johann Sebastian Bach, The Ossuary, Castle of Otranto, Darkness/Light/Darkness, and Manly Games.

- Jan Švankmajer, The complete short films. 1, Early shorts 1964-72. 2, Late shorts 1979-92. 3, Extras, BFI DVD Publishing, United Kingdom 2007

- Peter A. Hames (Editor), The Cinema of Jan Švankmajer: Dark Alchemy, 224 pp, Wallflower Press 2008, ISBN 9781905674459

- Jan Švankmajer, text by Lorenzo Codeli et al., cat. 128 p., Stamperia Stefanoni Bergamo 1997 (filmography overview)

- Jan Švankmajer: Het ludicatief principe, text by Edwin Carels et al., 72 p., 1991 (filmography overview)

- Bertrand Schmitt and Michel Leclerc: Les chimères des Švankmajer - Documentaire 2001, TV France

- Alchymická pec / Alchemical Furnace, 2020, directors Adam Oľha, Jan Daňhel, dokumentary film on Athanor, Jan Švankmajer, Eva Švankmajer, Jaromír Kallista, and others[116][117]

- Kunstkamera, 2022, 51 (113) min., pictorial guide to the work of Jan Švankmajer at Staňkov Castle.[118]

- The Cabinet of Jan Svankmajer, 1984 British surreal short stop-motion film by the Quay Brothers, a homage to Jan Švankmajer

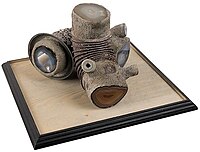

Jan Švankmajer, Mushroom (object), 1966

During his studies at secondary school, Jan Švankmajer was influenced by interwar surrealism and later especially by Paul Klee. At the turn of the 1950s and 1960s, he briefly turned to structural abstraction as an artist (Corossion, 1960, Slope, 1961).[119][120] Informel, however, was only the starting point from which he returned to concrete reality (The Great Corrosion, 1963). He gradually replaced existential melancholy with black humour and the creation of three-dimensional objects (Bottle-Drowned, 1964, Hourglass Isolation, 1964, Three Heads, 1965).[121]

From the mid-1960s onwards, information about foreign art reached Czechoslovakia, and Švankmajer was able to get acquainted with the works of Max Ernst, René Magritte and other surrealists. At the same time, he also discovered Rudolphine Mannerism, which influenced his late Informel. Arcimboldo became a lifelong obsession for him and the inspiration for many of his artworks, especially his collages and three-dimensional assemblages. He also dedicated a short film to him, Historia naturae (1967), which was associated with the creation of collages (Švank-meyers Bilderlexikon), etchings (Natural History) and objects (Natural History Cabinet) on the theme of fantasy zoology.

After Jan Švankmajer and his wife joined the Surrealist Group around Vratislav Effenberger, from 1971 to 1989 he contributed as author of texts and illustrations to anthologies and catalogues published by the group as samizdats (Otevřená hra / Open Game, Sféra snu / Sphere of Sleep, Proměny humoru / Transformations of Humour, Obrazotvorné prostory / Imaginative Spaces, Opak zrcadla / Opposite Mirror, Gambra / Gambra). At that time, he also experimented with spatial collage (the nativity scene The Birth of Antichrist, 1971) and, from 1974, especially with the tactile sense. In his writings, he consistently refuses to identify Surrealism with an aesthetic derived from certain founding figures or to reduce it to Surrealist artistic practices, but considers Surrealism to be a "world attitude" as an amalgam of philosophy, ideology, psychology, and magic, and therefore remains relevant.[122] According to him, act of creation is the result of psychic automatism or the materialization of an inner model. The idea is only a part of the creative process, not an impulse to it (Jan Švankmajer: The Ten Commandments).[123] Even in the making of a film, the script serves only as a starting point, but the process of filming itself awakens unplanned images in the unconscious and the final form is created only by the "chaotic authenticity" of the creative process.[124]

Švankmajer's Manifesto of New Applied Art, entitled The Magic of Objects (1979-1991), is an attempt to legalize irrationality in this field of art and to return the magical dimension to the outwardly utilitarian activity. Functionalism represented "hygienic purification", which returned applied art to the zero point. Surrealism began to occupy the space thus cleared and items of daily use were created that retained their utilitarian function without losing their magic.[125] Ceramics, which he and Eva Švankmajerová had been working on in the 1970s, was understood this way. The initial impulse was to create the objects of his desire and to satisfy his frustration with the unavailability of the objects of the Rudolf´s Kunstkammer, while eating from them or storing objects in them.[126]

Collages, drawings and prints

[edit]

Collages have been one of Švankmajer's key artistic devices since the 1960s. He understands them as a technical and at the same time noetic principle and, in addition to art cycles or spatial assemblages, he often uses them in short and feature films. The polarity of his creative expression lies in the connection between the high and the low, the aggressive and the lyrical, the fatal and the grotesque.[127]

In the early 1970s he began to create the Svank-meyers Bilderlexikon, as a kind of encyclopedia of the alternative world, including fictional fauna and flora, technical devices, architecture, ethnography and cartography. Švankmajer's significant inspiration is nature, from whose register he selects at will and creates anatomical re-creations of fanciful animal and bird creatures.[128] After two years of intensive work, the Bilderlexikon project remained a mere torso, and in the early 1970s there was no chance of publishing it in print. Therefore, the author selected ten collages and converted them by hand into graphic etching. The Bilderlexikon, which the author continued to develop in later years, includes the cycles Geography, Zoology, Technology (Masturbation Machine, 1972-1973), Architecture, Unconventional anatomy (1998), and Insects (Hexapoda) (2018). In 2016, he followed up his cartographic series with the collages', in which he pasted depictions of skin diseases from a medical atlas into historical maps (Sick Maps, 2016).

The collage series The Great Adventure Novel (1997-1999) was created as a reminiscence of his youthful predilection for adventure novels and a tribute to Max Ernst. Švankmajer first illustrated and redrew the illustrations and eventually used them as part of his collages.

In 1999, jointly with Eva Švankmajerová, he created a series of coloured lithographs with fantasy themes as part of a collective game invented by the Surrealists (Cadavre exquis, 1999). These works combine the liberating element of play with a critical analysis of psychosocial contents at different levels of consciousness.[128] In 2000, he created a series of collages entitled Yet Nothing Happens, in which the red head of the devil appears as a memento in romantic illustrations from the turn of the century.

Natural Science, Tab. 1 (1973), etching

Natural Science, Tab. 2 (1973), etching

Natural Science, Tab. 7 (1973), etching

Bilderlexikon - Hexapoda 4 (2016), litography

Bilderlexikon - Hexapoda 5 (2023), litography

Masturbation Machine Dana (1972), akvatint

Arcimboldesque head, 1975, colored akvatint

Japanese Ghost 3 (2011), woodcut

Erotic collage, 2016

Drooling Dog (2023), litography

Frottages and combined techniques

[edit]

At the same time Švankmajer was also engaged in coloured frottage (Man Greets a Demon, 1999) and collaged some frottage (Two Dogs, 1999). In his texts he increasingly deals with the warning signs of the crisis of civilization and the unfortunate state of human society.[129]

After the Prague Art Brut exhibition in 1998, Jan Švankmajer became interested in Art Brut artists and became a collector of these works[130] and together with Eva Švankmajerová began to create medium drawings.[131] They are usually based on frottage, created from randomly scattered substrates, similarly to fortune-telling from lines in the palm of the hand, coffee grounds, animal entrails, etc. This is followed by a kind of passive interpretation, where the hand complements this base with a drawing. Gradually an automatic ornament asserts itself, which is not merely decorative, but captures a certain "rhythm of the soul".[132] In this way, the medium's drawing approaches something archetypal, touching on the music of natural peoples, primal jazz, nursery rhymes and chants.[133][134] A side line is a series of drawings combined with collage, which the artist, in connection with his other compulsive obsession, called the Scatological Cycle (2017).

Shit watching the world, frottage, watercolour, ink, 2017

Karel Šebek today, assemblage, 2015

Manfred, the measure of your crimes is complete, assemblage, 2015

Inappropriate anatomy, combined technique, 2017

Decent fellatio, assemblage, ink on paper, 2017

In the 1970s, when Švankmajer was not allowed to make films, he looked for other ways to make a living. Eva Švankmajerová, who came from Kostelec nad Černými lesy, where there is a strong tradition of pottery, was close to ceramics. Together they started to create majolica and engobe clay pottery under the "pottery brand" JE and EJ Kostelec. The ceramic objects conceal cavities (Little and Big Demon, 1990) and invite exploration of the contents, but also touching, stroking or caressing, thus connecting key points of human sensuality. Some replicate various objects from Švankmajer's collections in the form of metaphors, thus representing ceramic rebirths of the original models (Arcimboldo's Head, 1981, Beethoven Portrayed by Arcimboldo, 1993).[135]

Jan Švankmajer considered their joint ceramic work to be an attempt to "return the outwardly utilitarian activity to its magical dimension and the legality to irrationality. The shape of the plate, cutlery, etc., can be used to evoke a number of associations during a meal and to eroticize the whole process of eating or to make it a cannibalistic-aggressive act."[136]

Švankmajer's objects encompass a range of artistic techniques, including ceramics combined with various objects (Masochistic alchemy, 1966). In the second half of the 1990s, he created the Alchemy series (Distillation, Fifth Essence, 1996). Objects in glass vitrines often depict some form of dialogue (Dialogue of bald, 1994, Dialogue on Life and Death, 1996), they are a reference to famous surrealist works (Eva's Shoes - a tribute to Méret Oppenheim, 2008) or represent a persiflage of the key Rosecrucian symbol of the mystical wedding - the fusion of king and queen, in the form of an assemblage of heterogeneous elements including an alchemical retort, shoes, brushes, bones, skull, etc. (Alchemical Wedding, 1994).[137]

Gestural sculpture and tactile objects

[edit]

Švankmajer's imagination, which allows him to animate any kind of material, also allows him to freely use materials when assembling puppets. He created the stone precursors of his puppets from coloured stones in his film Playing with Stones (1965) and later used a similar principle to build his gestural puppets from ceramic clay. The puppet thus lost its initially unambiguous character, ceased to be an actor and became a symbol, a kind of multi-significant "proto-fetish" (Marionette of the Unknown God, 2002, Death - a puppet from the series Knight, Death and the Devil, a tribute to Albrecht Dürer, 2012).

Unlike gestural painting, gestural sculpture is not mediated by any instrument and is a pure expression of the emotional and psychological state of the creator. In this work with matter, the primary concern is not visual sensation and aesthetic impact, but the record (fossil, diary) of immediate emotion. Gestural sculpture is intended to evoke associations linked to the sense of touch, to expand the field of tactile perception and to explore previously uncharted areas. The results are tactile objects designed to massage the body and to explore hitherto unknown erogenous zones, tactile portraits, tactile objects inspired by dreams and concealing unexpected tactile sensations,[138] tactile poems as linearly ordered tactile gestures recorded in fired ceramic clay, tactile marionettes assembled from pieces of roughly worked clay,[139] mantras and yantras.

Some of Švankmajer's gestural puppets seem to deny their own purpose as puppets - they have everything that belongs to a puppet, except that they cannot be guided. Their charm lies in their menacing and mocking stillness, in which the conventional sign is transformed into an unsettling poetic image, as liberating as it is confusing. His seemingly innocuous monsters, combining gesture-moulded clay with brushes, forks, sieves and other ordinary objects, exude an Ubu-esque preoccupation that mixes tragedy with humour, as well as a sarcastically mocking, almost animalistic cheekiness or contemptuous narcissism.[140] Švankmajer evokes tactile feelings in his films as well, as he assumes the existence of "tactile memory" - a planted tactile experience, related, for example, to sensuality.[141]In his film The Fall of the House of Usher, the gestural animation of clay, which here represents primordial matter (prima materia in the alchemical sense), is used to interpret the poem by E. A. Poe

Švankmajer's need to reveal the primary sources of human imagination is also related to his tactile objects. They were originally created as an experiment for the theme of interpretation within the Surrealist Group (Tactile portrait of E. Š, 1977),[142] but the result was so stimulating that he continued to work on them for seven years, when he was not allowed to make films, and they became one of the most interesting aspects of his work.[131] According to the artist, the sense of touch stands somewhere in the middle between the human senses, which provide purely objective (sight, hearing) or subjective (smell, taste) information. As a sense that has long had a purely utilitarian role and could not, for practical reasons, be aestheticized, the sense of touch retains a certain primitive connection to the world and an instinctive quality. Tactile sensation has one of the most important functions in eroticism, recalling associations linked to the deepest layers of the human unconscious (The Pleasure Principle, Tactile Object, 1996), elevating touch to one of the senses with the potential to inspire modern art.[143][144]

He considers the sense of touch to be the primordial sense through which the newborn child becomes acquainted with the surrounding world by means of touching the mother.[141] The sense of touch also plays a major role in the practical realization of erotic relationships. Erotic inspiration is present in Švankmajer's films as a manifest provocation and parody of utilitarian sex, sarcasm, black humour, interpretation of sexual deviance and existential anxiety.[145] In connection with the film Conspirators of Pleasure (1996), a series of artworks was created in which the Švankmajer family used tactile ceramic objects with sexual connotations (Animated Man and Animated Woman, 1996, Philosophy in the Bedroom - Realised Drawing, 1996, Philosophy in the Boudoir, 1996), etc.

Assemblages and objects

[edit]

Some of the works are related to Švankmajer´s early films from the 1960s (Playing with Stones, Historia naturae) and are part of a continuous creative process where each object becomes a stimulus for a new interpretation. The objects in the glass cases are intended for the Cabinet of curiosities project, whose function is initiatory rather than aesthetic. According to Effenberger, Švankmajer's Natural History Cabinet, containing phantom creatures that seem to have escaped scientific registration only to be discovered by the imagination of a rebellious child determined to protect poetic freedom, is a work of philosophical attitude rather than mere artistic sarcasm.[146] This cycle defies both the rationality of nature and the rationality of modern art. The symbolic merging of disparate elements contains a sense of the miraculous that has blended the tragic with the humorous in the human imagination since ancient cultures.[147]

Some of the most impressive objects "animate" minerals, combining bodies with cut agates and human limbs (Copulating Agates, Mineralogy with Three Legs, 2003). After 2011, he has been immersing some of his spatial objects in the Carlsbad Mineral Spring, creating "premature fossils". His "fossilized objects" become covered with a layer of mineral spring deposition, which gives them a uniform reddish-brown surface - a colour characteristic of Švankmajer's other works and originating in childhood memories. The artist thus attempts to bring the creation back to nature or at least to involve it in the creative process. The result, according to him, is a kind of "fossils of this fucking civilization as a prefigurement of its destruction" (The End of Civilization II?, 2011).[148]

Duel of roots, 2009

Animal-Clown, 2013

Fake Turtle, 2005

Meeting of Mineralogy with Zoology, 2017

Hedgehog, 2012

Handstan I, 2013

Mineralogic Elbows, 2010

Fetishes and reliquaries

[edit]

Puppets and assemblages are followed by objects that have been labelled by the artist directly as fetishes. These are not replicas of objects used for magical acts by natural peoples, nor do they have the aesthetic qualities of statues or masks (Flying Fetish, 2002).[149] Švankmajer's fetishism consists in linking an unfinished series of sources and contexts, which develop over time from the simpler to the more complex and, like a snowball, pile on top of each other the author's affects, emotions, knowledge and obsessions that give energy to the process. He thus proceeds against the meaning of the puppet itself, and in his creative mania he moves on to ever more ambiguous objects, whose external form and semantic functions metamorphose, thus increasing their symbolic quality.[150] Such a fetish is, for example, the nail-battered statue of the Crucified Christ in Lunacy.

The author declares of the fetish - "it is our creation to which we have attributed magical powers. We have charged it with desire and imagination and expect a miracle from it".[151] Fetishes are wounded to make them obey and fed to give them the power to fulfil our wishes. Jan Švankmajer imitated the ritual of the Congolese Africans, who hammer spikes and sharp pieces of metal into their fetishes to seal their covenant with them. He gathered assemblages of various remains of civilization in drawers from old furniture and "fed" them with blood and cornmeal. When everything began to deteriorate in the drawers in the sun and the fly larvae formed wounds in the matter, he completed the transformation with a heat gun, covered it with asphalt and buried it in ash. In this way, he partly returned to the informel starting point of his work (Drawer Fetish, 2015-2017).[152]

He creates a life-size Horse Fetish as the central object of his Kunstkamera, using a commercially available laminated horse body, which he combines with parts of various mammal skeletons. The resulting object is reminiscent of some of Peter Oriešek's airbrush drawings on the theme of Vanitas. Embedded in the belly of the fetish is one of his assemblage objects in a glass case - Pegasus Embryo.[153]

Švankmajer's modern reliquaries are shells of various animal remains, adorned with haberdashery props such as braids, faux pearls, buttons and tassels (Reliquary of the Sixteen Martyrs, 2015) and accompanied by a drawing. Some are figurative (Reliquary XV, 2016), while others are created spontaneously by the artist and are reminiscent in character of Švankmajer's medium frottage and drawings (Reliquary in Landscape, 2016).[154] In the reliquaries, the seemingly sacred and the profane intertwine and are transformed into co-carriers of a sarcastic vision, becoming parts of The Emperor's New Clothes in a sell-out of today's world of contentless institutions and hackneyed political, economic, or value clichés in general. Their message is not only subjectively grotesque, but above all psychologically and psychosocially aggressive (Coalition Partners, Resting Titan Before the End of the World, 2018).[155]

Wedding of Juan Miró with japanese female writer, 2016

Relikviary, 2016

Brushes, 2016

My favourite shoes, 2000, fetish

Woman with three breasts (2002)

African Marionette (2008)- Eva Švankmajerová: Baradla Cava /Jeskyně Baradla/, ed. Association of Analogon, Prague 1995, ISBN 80-238-0583-5

- Lewis Caroll, Alice in Wonderland (Jap.)

- Edogawa Rampo, The Living Chair (Jap.)

- Vratislav Effenberger, Eva Švankmajerová, Whips of Conscience, Dybbuk, Prague 2010, ISBN 9788074380273

- Kajdan (Kwajdan), a book of Japanese ghost stories[156]

Representation in collections (selection)

[edit]

- Museum of Art Olomouc

- Gallery of Fine Arts in Cheb

- Gallery of Modern Art in Hradec Králové

- Gallery Klatovy / Klenová

- Pražská plynárenská, a.s., Prague

- private collections at home and abroad

Author exhibitions (selection)

[edit]

- 1961 Kresby a tempery / Drawings and tempera, Semafor Prague

- 1963 Objekty / Objects, Viola theatre, Prague

- 1977 Infantile Lüste, Galerie Sonnenring, Münster (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 1983 Přírodopisný kabinet / Natural Science cabinet, Prague Film Club

- 1987 Bouillonnements cachés, Brussels and Tournai (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 1989 Retrospektive of films, Museum of Modern Art, New York

- 1991 La contamination des sens, Annecy (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 1991 Het ludicatief principe, Antwerp

- 1991 La fuerza de la imaginación, Valladolid

- 1992 Cyfleu breuddwydion / The Communication of Dreams, Cardiff, Bristol (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 1993 Das Lexikon der Träume, Filmcasino Vienna

- 1994 Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of the Senses, Central European Gallery and Publishing House, Prague

- 1994 El llentguatge de l'analogia, Sitges (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 1995 Athanor, Telluride, Colorado (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 1996 Haptic perception, Arcimboldo and Vanitas, London, Warsaw, Kraków (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 1997 Mluvící malířství, němá poezie / Talking painting, silent poetry, Obecní galerie Beseda, Prague (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 1997 Přírodopisný kabinet / Natural Science Cabinet, Gallery of Josef Sudek, Prague (s E. Švankmajerovou)

- 1998/2001 Anima, animus, animace (s E. Švankmajerovou), Gallery at the White Unicorn - Klatovy, Český Krumlov, Cheb, Hradec Králové, Jihlava, Washington, Rotterdam

- 1999 Jan Švankmajer, Musée d'art moderne et d'art contemporain (MAMAC), Nice

- 2002/2003 Eva Švankmajerová & Jan Švankmajer: De bouche à bouche, Annecy, Institut International de la Marionnette, Charleville

- 2003 Mediumní kresby a fetiše / Medium drawings and Fetishes, Nová Paka, Galerie Les yeux, Paris

- 2003/2004 Memoria dell´animazione - Animazione della memoria, Parma, Gallery of Plzeň City

- 2004 Jídlo - retrospektiva 1958-2004 / Food - retrospective 1958-2004, Riding Hall of Prague Castle (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 2004/2005 Syrové umění / Raw Art, Gallery Klatovy/Klenová, Moravian Gallery in Brno (with E. Švankmajerová)

- 2010/2011 Jan Švankmajer: Přežít svůj život / Survive Life, Artinbox Gallery, Prague

- 2011 Das Kabinett des Jan Švankmajer: Das Pendel, die Grube und andere Absonderlichkeiten, Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier

- 2011/2012 Jan Švankmajer: Krátké filmy z 60. let / Short films of the 1960s, Gallery of Fine Arts in Cheb

- 2012 Jan Švankmajer, Kerstin Engholm Galerie, Vienna

- 2012/2013 Jan Švankmajer: Možnosti dialogu. Mezi filmem a volnou tvorbou / Dimensions of Dialogue - Between Film and Free Artwork, Dům U Kamenného zvonu, Prague, Museum of Art, Olomouc

- 2014 Metamorphosis (V. Starevič, J. Švankmajer, Quay Brothers), Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art

- 2014/2015 Jan Švankmajer: Naturalia, Museum Kampa - Nadace Jana a Medy Mládkových / Foundation of Jan and Meda Mládek, Prague

- 2015 Cabinet of Jana Švankmajer (Ivan Melicherčík Collection), Danubiana Meulensteen Art Museum, Bratislava

- 2016 Jan Švankmajer: Lidé sněte / Dream on!, Artinbox Gallery Prague

- 2016 Jan Švankmajer: Objekty / Objects, DSC Gallery, Prague[157]

- 2018 Jan Švankmajer: Relikviáře, Galerie Millennium Prague

- 2019/2020 Jan Švankmajer, Eva Švankmajerová: Move little hands… "Move!", Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau, Dresden[158]

- 2023 Jan Švankmajer: Nepřírodopis / Nonnatural Science, Museum Rýmařov and Octopus Gallery

- 2023 Jan Švankmajer: Nepřirozené příběhy / Nonnatural Stories, Kebbel-Villa | Oberpfälzer Künstlerhaus, Schwandorf

- 2024 Eva Švankmajerová / Jan Švankmajer, DISEGNO INTERNO, Gallery of Central Bohemian Region, Kutná Hora

Collective exhibitions (selection)

[edit]

- 1968/1969 Art tchécoslovaque, Maison des Jeunes et de la Culture (MJC), Orléans

- 1969 Ausstellung tschechischer Künstler, Galerie Riehentor, Basel

- 1971 45 zeitgenössische Künstler aus der Tschechoslowakei. Malerei, Plastik, Grafik, Glasobjekte, Baukunst, Cologne

- 1981 Groupe surréaliste tchécoslovaquie, Galerie Phasme, Geneva

- 1991-1992 Třetí archa (Skupina československých surrealistů) / Third Arc (Czechoslovak Surrealist Group), Mánes, Prague

- 1993 Das Umzugskabinett, Galerie 13, Hanover

- 1994 Europa, Europa: Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel- und Osteuropa, Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn

- 1997 Očima Arcimboldovýma / By Arcimboldo´s Eyes, National Gallery Prague

- 2000 Tschechischer Surrealismus und Art Brut zum Ende des Jahrtausends, Palais Pálffy (Österreichisches Kulturzentrum), Vienna

- 2003/2004 World of Stars and Illusions: Gems of the Czech Film Poster Tradition, Czech Centre, New York City, London, Los Angeles, Dresden, Hong Kong, Macau

- 2004 Tsjechische l´art brut tchèque, Musee d'art spontane (Museum voor spontane kunst), Brussels

- 2007 Skupina Máj 57 / Máj 57 Group, Prague Castle, Císařská konírna / Imperial Stables

- 2007/2008 Exitus: Tod alltäglich, Vienna Künstlerhaus

- 2009 Spolek výtvarných umělců Mánes (1887 - 2009) / Verein Bildender Künstler Manes (1887 - 2009): Historie a současnost významného českého uměleckého spolku / Geschichte und Gegenwart des Tschechischen Kunstvereins, Saarländische Galerie – Europäisches Kunstforum e.V., Berlin

- 2009/2010 Gegen jede Vernunft: Surrealismus Paris - Prag, Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen

- 2012 Jiný vzduch: Skupina česko-slovenských surrealistů 1990–2011 / Other Air: the Czech-Slovak Surrealist Group 1990-2011, Old Town Hall, Prague

- 2013/2014 Czech Posters for Film. From the Collection of Terry Posters, National Film Archive of Japan, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Kyoto

- 2014 Metamorfosis: Visiones fantásticas de Starewitch, Švankmajer y los hermanos Quay, Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

- 2015 Einfach phantastisch!, Barockschloss Riegersburg

- 2021/2022 Surrealism Beyond Borders, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, Tate Modern, London[159][160]

- 2023 À flanc d'abîme: Surréalisme et Alchimie, Centre International du Surréalisme et de la citoyenneté mondiale, Saint-Cirq-Lapopie

- 2024 Kafkaesque - Franz Kafka & současné umění / Franz Kafka & Contemporary Art, DOX, Centrum současného umění / Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague

Jan Švankmajer writes down his dreams, and then translates some of them into film scripts or theatre one-act plays.[161]

In his literary texts, he makes no secret of his sceptical view of the current form of human civilisation, which is destroying the spiritual essence of man with its pragmatism, utilitarianism and rationalism. The genre that, in his opinion, most accurately corresponds to its present situation, is the black grotesque. Švankmajer writes, that state is an instrument of repression and the common man a victim of manipulation, as an actor in his film Faust. Freedom and personal integrity can only be preserved through personal revolt. Art has been replaced by advertising and entertainment shows, and consumerism has become the new ideology.[162]

Humanity, perhaps out of impatience, tries to introduce all noble and humanistic ideas first in a swift and bloody way, and only after the failure of this brutal variant does it embark on the lengthy path of peaceful evolution.[163] Švankmajer's apocalyptic visions foresee a post-civilizational disintegration of nation-states, coupled with the return of a new feudalism in the form of some kind of principalities, controlled by multinational concerns, where ordinary people will once again become serfs.[129]

In 1983 he published his work "Touch and Imagination" in five copies as a samizdat, which was then reprinted in 1994 by Kozoroh Publishing.[22]

- Luboš Jelínek, Jan Švankmajer (eds.): Jan Švankmajer - Grafika. Obrazový soupis 1972 - 2023 / Prints, Pictorial inventory 1972 – 2023, 97 p., Gallery Art Chrudim, Gallery Vltavín, Prague 2023, ISBN 978-80-908597-0-8

- Jan Švankmajer: Švank-mayers Bilderlexikon, 320 s., Dybbuk, Prague 2022, ISBN 978-80-7690-036-3

- Jan Švankmajer, Jednotný proud myšlení aneb život se rodí v ústech (Velký dobrodružný román) / The Unified Stream of Thought, or Life is Born in the Mouth (A great adventure novel), Dybbuk, Praha, 2020, ISBN 978-80-7438-220-8

- František Dryje (ed.): Jan Švankmajer, Cesty spasení / Paths of Salvation, Dybbuk, Prague 2018, ISBN 978-80-7438-180-5

- Jan Švankmajer, Touching and Imagining: An Introduction to Tactile Art, I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd, London 2014, ISBN 978-1-78076-146-6

- František Dryje (ed.): Jan Švankmajer, Síla imaginace / The Power of Imagination, Dauphin (ISBN 80-7272-045-7) and Mladá fronta (ISBN 80-204-0922-X), Prague 2001

- Eva Švankmajerová, Jan Švankmajer, Imaginativní oko, imaginativní ruka / Imaginative Eye, Imaginative Hand, Vltavín, Prague 2001, ISBN 80-902674-7-5

- Evašvankmajerjan: Anima, animus, animation, catalogue and bibliography (cs., en., de.), 185 p., Arbor vitae, Slovart s.r.o, Prague 1997 ISBN 80-901964-3-8

- Jan Švankmajer, Hmat a imaginace: Úvod do taktilního umění – Taktilní experimentace 1974–1983 / Touch and Imagination: an Introduction to Tactile Art - Tactile Experimentation 1974-1983, 235 p., samizdat 1983, published by Kozoroh, Prague 1994

Collective Proceedings

[edit]

- František Dryje, Šimon Svěrák, Roman Telerovský (eds.), Princip imaginace / The Principle of Imagination, Spolek Analogon, Prague 2016

- Opak zrcadla / The Opposite of a Mirror, anthology of the Surrealist Society in Czechoslovakia, Genf Prague 1985, samizdat

- Proměny humoru, Transformations of Humour, catalogue for the thematic exhibition of the Surrealist Society in Czechoslovakia, Genf Prague 1984, samizdat

- Sféra snu / Sphere of Dream, catalogue for the thematic exhibition of the Surrealist Society in Czechoslovakia, Le-La, Genf Prague 1983, samizdat

- Otevřená hra / Open Game, Prague 1979, samizdat

- Le-La 11, 12 (dedicated to the Surrealist Society in Czechoslovakia), Genf Prague 1977, samizdat

- Films directed by Jan Švankmajer

- Jiří Trnka, Czech animator and puppeteer

- Karel Zeman, Czech animator and filmmaker

- Jiří Barta, Czech stop motion animator

- Ladislaw Starewich, Polish animator and puppeteer

- The Torchbearer, a film by Jan Švankmajer's son, Václav Švankmajer

- List of stop motion films

- ^ IFFR. "Jan Švankmajer". IFFR. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ a b Nádvorníková A, in: NEČVU, Dodatky, 2006, s. 769

- ^ a b c Interview With Jan Švankmajer, Karolína Bartošová, Loutkář 1, 2016, p. 3-8

- ^ František Dryje, in: Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of senses, 1994, pp. 68-69

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Film, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, p. 95

- ^ a b c d e Slovník českých a slovenských výtvarných umělců 1950–2006 (XVII. Šte – Tich), 2006, pp. 182-184

- ^ Švankmajer, Jan (2012). Jan Švankmajer: Dimensions of Dialogue, Between Film and Fine Art. Řevnice: Arbor Vitae. p. 63. ISBN 978-80-7467-016-9. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Krčálová M, Sklizeň / Harvest, 2022, p. 24

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: F. Dryje, ed., Síla imaginace / Power of imagination, 2001, p. 35

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, p. 17

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Cesty spasení / Paths of salvation, 2018, p. 194

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 64

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 65

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 66

- ^ Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of senses, 1994, p. 99

- ^ Švankmajer J, 2001, pp. 118-120

- ^ a b Dryje F, in: Eva Švankmajerová, Jan Švankmajer, Anima, animus, animation, 1997, p. 10-12

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Eva Švankmajerová, Jan Švankmajer, Anima, animus, animace, 1997, p. 33

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 82

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 81

- ^ Dryje F: Jiný zrak, in: Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of senses, 1994, p. 9

- ^ a b c Dagmar Magincová (ed.), 1997, p. 171

- ^ Slovník české literatury po roce 1945 / Dictionary of Czech Literature after 1945: Analogon

- ^ Stanislav Ulver, in: F. Dryje, ed., Síla imaginace / The Power of Imagination, 2001, p. 36

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 128

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Out of my head, The Guardian, 2001

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Droga / Drug, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, pp. 139-141

- ^ Martin Stejskal, in: Eva Švankmajerová, Jan Švankmajer, Anima, animus, animace, 1997, p. 106

- ^ Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of senses, 1994, p. 100

- ^ Eva Švankmajerová, in: Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of senses, 1994, pp. 60–61

- ^ Horní Staňkov Castle

- ^ Dryje F: Jiný zrak, in: Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of senses, 1994, s. 10

- ^ Terry Gilliam: The 10 best animated films of all time, Guardian 2001

- ^ Marie Benešová, La contamination des sens, Tvar 8, 12.9.1991

- ^ Czech Film Commission: Athanor

- ^ Cardiff Animation Festival (CAF)

- ^ The Magic Art of Jan Svankmajer, BBC Two, 1992

- ^ John Coulthart, The Magic Art of Jan Svankmajer, 2023

- ^ Britské pocty Janu Švankmajerovi, Lidové noviny 1.4.1992

- ^ Ivo Purš, in: Anima, animus, animace, 1997, p. 96

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, p. 136

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Anima, animus, animace, 1997, pp. 115-119

- ^ Tereza Brdečková: Zakázané území - souborné dílo Jana Švankmajera / The Forbidden Territory - The Complete Works of Jan Švankmajer, Respekt 1994, č. 18, s. 15

- ^ Jan Kerbr, Divadelní noviny 12, 2003, p. 10

- ^ Michal Bregant: Jan Švankmajer, Doctor honoris causa, Akademie múzických umění, Praha 2003

- ^ Peter Kováč, Jan Švankmajer otevírá bilanční výstavu ke svým sedmdesátinám, 2004

- ^ Jindřich Rosendorf, Výtvarnou událostí roku je výstava Jana a Evy Švankmajerových v Galerii města Plzně, Lidové noviny 24.2.2004

- ^ Special Prize for Outstanding Contribution to World Cinema: Jan Švankmajer, KVIFF, 2009

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Síla imaginace / Power of Imagination, 2001, pp. 213-231

- ^ Tate Modern: Jan Švankmajer, Insects

- ^ Tomáš Stejskal: Švankmajer's Insect is like another cabinet of curiosities. A film about the decline of civilization premieres in Rotterdam, 2018

- ^ Radka Polenská: Švankmajer překračuje společenská tabu / Švankmajer breaks social taboos, iDNES 14.3.2007, B6

- ^ Internet Movie Database: Jan Švankmajer, overview of awards

- ^ Analogon magazine

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 421

- ^ International Movie Database: Václav Švankmajer

- ^ Czech TV: Veronika Hrubá

- ^ Golden Gate Persistence of Vision Award: Jan Švankmajer, 1997

- ^ Andrzej Wajda Freedom Prize: Jan Švankmajer (2001)

- ^ Švankmajer awarded for life’s work in Segovia, Radio Prague International, 2010

- ^ Čas je jediný arbitr, říká oceněný filmař a animátor Švankmajer, Lidovky, 2014

- ^ Česko Slovenská filmová databáze: Jan Švankmajer

- ^ Alchymická pec, Czech TV

- ^ J. Š., in: Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation ov senses, 1994, s. 13

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 105–107

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 108–111

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, p. 17

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Apoteóza loutkového divadla, in: Cesty spasení / The Apotheosis of Puppet Theatre, in: Paths of Salvation 2018, s. 191–193

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, pp. 39–41

- ^ Hames P, The Case of Jan Švankmajer, in: Peter Hames, Czechoslovak New Wave, 2008, p. 235

- ^ a b Posedlost Jana Švankmajera / The obsession of Jan Švankmajer, Lidové noviny 16.10.1993

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, s. 84-87

- ^ a b c Georgia Chryssouli, Surreálně lidské: svět sebeničivých loutek Jana Švankmajera, Loutkář 1, 2016, s. 9-11

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, p. 80

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: S. Ulver, Mediumní kresby, fetiše a film, Film a doba 2008, p. 158-160

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, pp. 25, 28

- ^ Petr Fischer, Revoluce imaginace, Lidové noviny 9.3.2002

- ^ Stanislav Ulver, interview with Jan Švankmajer, Film a doba 1, 2015, p. 8-13

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Civilizace jednou zkolabuje, DNES 28.6.2008

- ^ Darina Křivánková: Jan Švankmajer, Reflex 27, 2009, s. 59

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, p. 113

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Paths of Salvation, 2018, p. 129

- ^ Hynek Glos, Petr Vizina, 2016, p. 77

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Poslední trik pana Schwarcewalldea a pana Edgara, Česká televize

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Johann Sebastian Bach - Fantasia G-moll, video

- ^ Jan Svankmajer (1965): A Game With Stones, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Rakvičkárna, Česká televize

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Et cetera, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Historia naturae, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Zahrada, Česká televize

- ^ Jan Svankmajer: Picnic with Weissmann, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Byt, Česká televize

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Tichý týden v domě, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Kostnice, Česká televize

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Don Šajn, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Jabberwocky, YouTube video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Leonardův deník, Česká televize

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Otranský zámek, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Zánik domu Usherů, Česká televize

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Možnosti dialogu, YouTube

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Do pivnice, YouTube video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Kyvadlo, jáma a naděje, YouTube video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Mužné hry, Česká televize

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Another Kind of Love, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Tma, světlo, tma, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Zamilované maso, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Flora, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Autoportrét, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: Konec stalinismu v Čechách, video

- ^ Jan Švankmajer:Food on YouTube

- ^ Da Films: Jan Švankmajer

- ^ MFF Karlovy Vary: Přežít svůj život

- ^ Švankmajer chystá film Hmyz za 40 milionů, inspirací mu je Čapek, IDnes.cz, 25. dubna 2011

- ^ Jan Švankmajer prépare une comédie qui donnera le frisson, Radio.cz, 03-05-2011, Václav Richter (in French)

- ^ Švankmajer: Filmy, jaké dělám, tahle civilizace nepotřebuje, ČT 24, 11. 7. 2014

- ^ ČSFD: Alchymická pec

- ^ KVIFF TV: Alchemical Furnaca

- ^ ČSFD: Kunstkamera, 2022

- ^ Mahulena Nešlehová (ed.), Český informel, Průkopníci abstrakce z let 1957–1964 / Czech Informel, Pioneers of Abstraction 1957-1964, 268 p., Prague City Gallery, SGVU Litoměřice, 1991

- ^ Dryje F: Jiný zrak, in: Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů, 1994, s. 7

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: F. Dryje, ed., Síla imaginace / Power of Imagination, 2001, s. 13-16

- ^ Švankmajer J, 2001, p. 129

- ^ Jan Švankmajer: The Ten Commandments (in Czech)

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, s. 231-233

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, p. 196-197

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Nádobí / Utensils, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, p. 200

- ^ Alena Nádvorníková, in: Imaginativní oko, imaginativní ruka, 2001, p. 58

- ^ a b Jan Kříž, in: Imaginativní oko, imaginativní ruka, 2001, p. 6

- ^ a b Jan Švankmajer, Paths of Salvation, 2018

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, p. 371

- ^ a b Janda J, 2004, p. 189

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Mediumní kresby / Medium drawings, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, s. 71

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Imaginativní oko, imaginativní ruka, 2001, p. 42

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, p. 236-237

- ^ Alena Nádvorníková, in: Transmutace smyslů, 1994, s. 58-59

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, p. 121

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, pp. 310-311

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Hra na Arcimboldovy živly / Playing Arcimboldo's Elements, 1978, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, p. 80

- ^ Jiří Hůla: Prosím dotýkati se - Jan Švankmajer, Denní Telegraf 25.10.1994

- ^ Jan Gabriel, To Touch Means Nothing, in: Food, 2004, pp. 190-191

- ^ a b Jan Švankmajer, in: Eva Švankmajerová, Jan Švankmajer, Anima, animus, animation, 1997, p. 85

- ^ J.Š., Přípravné poznámky k taktilnímu portrétu E.Š. / Preliminary notes to the tactile portrait of E. Š, in: Evašvankmajerjan, 1998, p. 9

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Imaginativní oko, imaginativní ruka / Imaginative eye, imaginative hand, 2001, p. 20

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Z taktilního deníku / From a tactile diary, in: Jídlo / Food, 2004, pp. 84-87

- ^ Janda J, 2004, p. 190

- ^ Vratislav Effenberger, in: Simeona Hošková, Květa Otcovská (eds.), Jan Švankmajer, Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of senses, 1994, pp. 17-18

- ^ Vratislav Effenberger, in: F. Dryje, ed., Síla imaginace / Power of imagination, 2001, pp. 17-18

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, pp. 244-245

- ^ Bertrand Schmitt, in: František Dryje, Bertrand Schmitt (eds.), 2012, pp. 386-388

- ^ František Dryje, Fetiš a médium, Film a doba 2008, s. 161-163

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, s. 300

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, pp. 194-197

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, pp. 198-199

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, pp. 200-209

- ^ František Dryje, Co člověk spojil, pánbůh nerozlučuj, úvod výstavy Galerie Millennium, 2018

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, s. 100-117

- ^ The Prague Gallery selected something from Švankmajer, Czech TV, 2016

- ^ Fajt exhibits Švankmajer in Germany, Aktuálně.cz, 2020

- ^ České centrum London, film Byt od Jana Švankmajera v galerii Tate Modern, 2022

- ^ Juliet Jacques, Tate Modern’s Reimagining of International Surrealism, Frieze 2022

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, Jedenáct aktovek / Eleven one-act plays, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, pp. 266–293

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, pp. 112–115

- ^ Jan Švankmajer, in: Solařík B (ed.), 2018, p. 149

- Bruno Solařík (ed.), Jan Švankmajer, 304 p., Albatros Media a.s., Prague 2018, ISBN 978-80-264-1814-6

- Keith Leslie Johnson, Jan Švankmajer: Animist Cinema, 210 p., University of Illinois Press 2017, ISBN 978-0-252-08302-0