Jorge Manrique (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Spanish poet

| Jorge Manrique | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Jorge Manrique by Juan de Borgoña Portrait of Jorge Manrique by Juan de Borgoña |

|

| Born | c. 1440Paredes de Nava, Palencia, or Segura de la Sierra, Jaén |

| Died | April 24, 1479(1479-04-24) (aged 38–39)Santa María del Campo Rus, Cuenca |

| Occupation(s) | Poet and soldier |

| Spouse | Guiomar de Castañeda |

| Children | 2 Luis Manrique de CastañedaLuisa Manrique de Castañeda |

| Parents | Rodrigo Manrique (father)Mencía de Figueroa (mother) |

| Relatives | House of Lara |

Jorge Manrique (c. 1440 – 24 April 1479) was a major Castilian poet, whose main work, the Coplas por la muerte de su padre (Verses on the death of Don Rodrigo Manrique, his Father), is still read today. He was a supporter of the queen Isabel I of Castile, and actively participated on her side in the civil war that broke out against her half-brother, Enrique IV, when the latter attempted to make his daughter, Juana, crown princess. Jorge died in 1479 during an attempt to take the castle of Garcimuñoz, defended by the Marquis of Villena (a staunch enemy of Isabel), after Isabel gained the crown.

Manrique was a great-nephew of Iñigo López de Mendoza (marquis of Santillana), a descendant of Pero López de Ayala, chancellor of Castile, and a nephew of Gómez Manrique, corregidor of Toledo, all important poets of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. He was, therefore, a member of a noble family of great literary consequence. The topic of his work was the tempus fugit.

Jorge Manrique wrote love lyrics in the courtly-love tradition and two satires. These called canciones (songs), esparsas (short poems, generally of a single stanza), preguntas y respuestas (questions and answers), and glosas de mote (literally, "interpretations of refrains"; see villancico). The first edition of the Cancionero general of Hernando del Castillo (1511) has the most complete selection of Manrique's poems, but some of the lyrics appear in other early editions and manuscripts.

Coplas por la Muerte de su Padre

[edit]

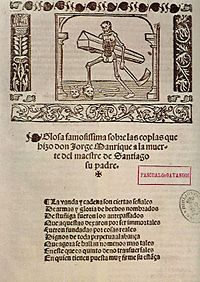

First page of the Coplas by Jorge Manrique.

Coplas por la Muerte de su Padre (English: "Stanzas about the Death of his Father") is Jorge Manrique's best composition. In fact, Lope de Vega pronounced it in humbled admiration to its superior craftmanship, "worthy to be printed in letters of gold". It is a funeral eulogy dedicated to the memory of Rodrigo Manrique (his father), who died on 11 November 1476 in Ocaña. Jorge thought that his father led a life worth living. He makes a reference to three lives:

- the terrestrial life that ends in death

- the life of the fame, that lasts longer (Kleos Greek)

- the eternal life after death, that has no end.

Stanzas 1-24 talk about an excessive devotion to earthly life from a general point of view, but features some of the most memorable metaphors in the poem. Among other things, life is compared to a road filled with dangers and opportunities and to a river that ends in the sea:

I

| | Recuerde el alma dormida avive el seso e despierte contemplando cómo se pasa la vida, cómo se viene la muerte tan callando; cuán presto se va el placer, cómo, después de acordado, da dolor; cómo, a nuestro parecer, cualquiera tiempo pasado fue mejor. | O let the soul her slumbers break, Let thought be quickened, and awake; Awake to see How soon this life is past and gone, And death comes softly stealing on, How silently! Swiftly our pleasures glide away, Our hearts recall the distant day the pain The moments that are speeding fast We heed not, but the past,—the past, More highly prize. | | ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

III

| | Nuestras vidas son los ríos que van a dar en la mar, que es el morir. Allí van los señoríos derechos a se acabar e consumir. allí los ríos caudales, allí los otros medianos e más chicos, allegados, son iguales los que viven por sus manos e los ricos. | Our lives are rivers, gliding freeTo that unfathomed, boundless sea,The silent grave!Thither all earthly pomp and boastRoll, to be swallowed up and lostIn one dark wave. Thither the mighty torrents stray,Thither the brook pursues its way,And tinkling rill,There all are equal; side by sideThe poor man and the son of prideLie calm and still. | | ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

The section invokes general examples of human waywardness that one may encounter along the road leading to heaven or hell, but then gives some examples of infamous deaths drawn from contemporary Spanish history. These examples are introduced by the rhetorical questions called ubi sunt (Where are they?) in stanzas 15-24:

XVI

| | ¿Qué se hizo el rey don Joan? Los infantes d'Aragón ¿qué se hizieron? ¿Qué fue de tanto galán, qué de tanta invinción como truxeron? ¿Que fueron sino devaneos, qué fueron sino verduras de las eras, las justas e los torneos, paramentos, bordaduras e çimeras? | Where is the King, Don Juan? WhereEach royal prince and noble heirof Aragon?Where are the courtly gallantries?The deeds of love and high emprise, In battle done? Tourney and joust, that charmed the eye, And scarf, and gorgeous panoply,And nodding plume,What were they but a pageant scene?What but the garlands, gay and green,That deck the tomb? | | -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

The last part of the poem is devoted to his father and talks about the life of fame and the possibility of continuing to live in the memories of the living, when one is great and has accomplished great deeds while living (stanzas 25-32). The poem ends with a small dramatic dialogue in which don Rodrigo confronts a personified Death, who deferentially takes his soul to Heaven (stanzas 33-39). A final stanza (40) gives consolation to the family.

The language Manrique uses is precise, exact, without decoration or difficult metaphors. It appears to focus on the content of what is said and not on how it is said. The poem has forty stanzas, each composed of twelve eight- and four-syllable lines that rhyme ABc ABc DEf DEf. Every third line is a quebrado (half line). The verse form is now known as the copla manriqueña (Manriquean stanza), because his poem was so widely read and glossed that he popularized the meter. Its alternation of long and short lines, and their punctuation, made the verses flexible enough to sound somber or light and quick.

Coplas por la muerte de su padre has been translated at least twice, once by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The translations of stanzas I, III, and XVI provided above are by Longfellow. However, the Longfellow translation has been criticized as not being faithful to the original. Longfellow's translation is considerably more florid than the original. For example, the famous lines "Nuestras vidas son los ríos/ que van a dar en la mar,/ que es el morir," which reads in Longfellow as "Our lives are rivers, gliding free/ To that unfathomed, boundless sea,/ The silent grave!" literally translates as "Our lives are rivers/ That will lead to the sea/ Which is death."

- Domínguez, Frank A. Love and Remembrance: The Poetry of Jorge Manrique. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1989.

- Domínguez, Frank A. "Jorge Manrique" in Castilian Writers, 1400-1500 Vol. 286. Detroit: Gale, c2004. (The article can be accessed as well in electronic format through the database Literature Resource Center at Gale in participating libraries.)

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. Coplas de Don Jorge Manrique. Boston: Allen & Ticknor, 1833.

- Marino, Nancy. Jorge Manrique's Coplas por la muerte de su padre: A History of the Poem and Its Reception. (Colección Támesis, A/298.) Woodbridge, UK: Tamesis, 2011

- Serrano de Haro, Antonio. Personalidad y destino de Jorge Manrique. Madrid: Editorial Gredos, 1966.

- Salinas, Pedro. Tradición y originalidad Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana 1947

- Brenan, Gerald. The Literature of the Spanish people, Cambridge, 1951.

- Jorge Manrique's collected works (in Spanish) (Cortina ed.). Cervantes Virtual. 1979.

- "Gloss of Jorge de Montemayor" (in Spanish). Cervantes Virtual. Archived from the original on 2006-07-24.

- Works by or about Jorge Manrique at the Internet Archive

- Works by Jorge Manrique at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)