Lithuanian talonas (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Former currency of Lithuania

"Talonas" redirects here. For the fictional deity, see Talona.

Lithuanian talonas

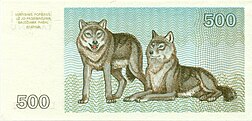

Final edition of 500 talonai displaying gray wolves Final edition of 500 talonai displaying gray wolves |

|

|---|---|

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | none |

| Subunit | |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 5 August 1991 |

| Date of withdrawal | 25 June 1993 |

| Replaced by | Lithuanian litas |

| User(s) | Lithuania |

| This infobox shows the latest status before this currency was rendered obsolete. |

The talonas (from a Lithuanian word for "coupon")[1] was a temporary currency issued in Lithuania between 1991 and 1993.[2] It replaced the Soviet ruble at par and was replaced by the litas at a rate of 100 talonai = 1 litas.[3] The talonas was only issued as paper money.

The first talonas reform

[edit]

| Year | Inflation rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| In Lithuania | In Russia | |

| 1991 | 225 | N/A |

| 1992 | 1,100 | 2,508.8 |

| 1993 | 409 | 849.9 |

| 1994 | 45.1 | 215.1 |

| 1995 | 35.7 | 175.0 |

| 1996 | 13.1 | 21.8 |

| 1997 | 8.4 | 11.0 |

| 1998 | 2.4 | 84.4 |

| 1999 | 1.5 | 36.5 |

| Sources [1], [2], [3] |

Example of the first edition 100 talonai, with a wisent depicted.

On 5 August 1991, as a response to public complaints about inflation, the Lithuanian government introduced the talonas, paid out as a supplement to the salaries in rubles.[4][5] It was a quick and unforeseen reform pushed by the Prime Minister of Lithuania Gediminas Vagnorius. At first, it was very similar to ration coupons: every person received 20% of his/her salary in talonas up to a maximum of 200 talonai. In order to buy goods other than food, the price had to be paid in rubles and again in talonas (for example, if a product cost 50 rubles, a person had to pay 50 rubles and 50 talonai to buy it). That was done to prevent foreigners from other Soviet states to take goods out of the country - foreigners who only had rubles were unable to acquire the goods.[6]

This system was widely criticized. First of all, in no way did it address the reasons why there were shortages of goods, i.e., it did not promote supply; it just limited demand. Also, the demand for expensive goods (like home appliances) dropped sharply because people needed a lot of time to accumulate the necessary amount of talonas to buy them. It caused bottlenecks in the supply chain and further damaged already troubled production. In addition, the scheme could not prevent hyperinflation of the ruble because the talonas was not an independent currency; it was a supplementary currency with a fixed exchange rate to the ruble. The system tried to encourage Lithuanians to save 80% of their salaries. But people accumulated their rubles and had nowhere to spend them. It led to the inflation of goods that did not require the talonas (like food or goods on the black market).

0.10 talonas

0.20 talonas

0.50 talonas

1 talonas

3 talonai

5 talonai

10 talonai

25 talonai

50 talonai

100 talonai

The second talonas reform

[edit]

In the summer of 1992, everybody anticipated that the talonas would shortly be replaced by a permanent currency, the litas. Lithuania was desperately lacking cash (some workers were paid in goods rather than in cash) as Russia tightened its monetary policy. In addition, litas coins and banknotes had already been produced and shipped to Lithuania from abroad. However, on 1 May 1992, it was decided to reintroduce the talonas as an independent, temporary currency to circulate alongside the ruble in hopes to deal with inflation. A dual currency system was created. On 1 October 1992, the ruble was completely abandoned and replaced by the talonas.[7] Lithuania was the last of the Baltic states to abandon the ruble. The self-imposed deadlines to introduce the litas were continuously postponed without clear explanations.

Nicknamed "Vagnorkės" or "Vagnoriukai" after Gediminas Vagnorius or "zoo tickets" after various animals native to Lithuania featured on the notes, the talonas did not gain public trust or respect. The banknotes were small and printed on low quality paper. People were reluctant to use them. Nevertheless, the talonas served its purpose: inflation at the time was greater in Russia than in Lithuania. Inflation in 1992 rose steadily due to an energy price spike after Russia increased oil and gasoline prices to world levels and demanded to be paid in hard currency.

On 25 June 1993, the litas was introduced at the rate of 1 litas = 100 talonas.[8] Worthless talonas were recycled into toilet paper in the Grigiškės paper factory.[9][10]

In 1991, notes were issued in denominations of 0.10, 0.20, 0.50, 1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 talonas. In 1992, notes were issued for 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, and 500 talonas, followed by new designs of the 200 and 500 talonas notes in 1993.

Inline

- ^ Berlin, Howard M. (June 14, 2015). World Monetary Units: An Historical Dictionary, Country by Country. McFarland. ISBN 9781476606736 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Veidas - 2015 March 06, Nr.9" (PDF). Veidas. 2015-06-02. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-06-13. Retrieved 2024-06-13. Laikinieji pinigai – bendrieji talonai, vadinti tiesiog „vagnorkėmis" (pagal tuomečio premjero Gedimino Vagnoriaus pavardę), ėmė keisti SSRS rublius. Nuo 1992 m. spalio 1 d. „vagnorkės" tapo vienintele teisėta mokėjimo priemone – Lietuva išėjo iš rublio zonos.

- ^ "Litui – 30: nacionalinės valiutos įvedimo istorija ir paslaptys". 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). 2023-06-29. Archived from the original on 2024-06-13. Retrieved 2024-06-13. Vyriausybei ir Lietuvos bankui buvo pavesta „patvirtinti laikinų pinigų-talonų išėmimo iš apyvartos tvarką ir sąlygas, nustatant, kad vienas litas yra lygus 100 laikinųjų pinigų-talonų".

- ^ Linzmayer, Owen. The Banknote Book: Lithuania. www.BanknoteNews.com. 2013. San Francisco, CA. http://www.banknotebook.com

- ^ "317 Dėl bendrųjų talonų prekėms įsigyti supirkimo ir pardavimo tvarkos".

- ^ Vaitelė, Tomas (2023-10-01). "Avantiūra, užtikrinusi fiskalinę laisvę: kaip „pempės", „meškutės" ar „drieželiai" Lietuvą nuo rublio tragedijos gelbėjo". lrt.lt (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 2024-06-13. Retrieved 2024-06-13. „Situacija tokia, kad išduodamas gyventojams tam tikras kiekis talonų, jie gali jais atsiskaityti. Mes vis dar esame rublio sistemoje, pas mus cirkuliuoja rublis ir, pavyzdžiui, mokant už prekę sumokamas tam tikras kiekis rublių ir atitinkamas kiekis talonų. Tokiu būdu prekės išlaikomos Lietuvoje", – teigė T. Grėlis.

- ^ "Litui – 30: nacionalinės valiutos įvedimo istorija ir paslaptys". Lietuvos bankas (in Lithuanian). 2023-06-28. Retrieved 2024-06-13. 1992 m. spalio 1 d. vienintele teisėta mokėjimo priemone Lietuvoje paskelbtas nacionalinis piniginis vienetas talonas.

- ^ "Talonai". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). 2023-05-11. Archived from the original on 2024-06-13. Retrieved 2024-06-13. 1993 talonai pakeisti litais (santykiu 100:1).

- ^ "Šiaulių kraštas newspaper - 1994 03 18 (Fri) - Nr.52(737)" (PDF). Šiaulių kraštas. 2024-06-13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-06-13. Retrieved 2024-06-13. "Grigiškės" buvo sunaikinta 2520 kilogramų pirmųjų "kapeikinių" talonų. Sunaikinus juos, bus atvežti kiti vėliau apyvartoje cirkuliavę bendrieji talonai.

- ^ Gvozdaitė, Laura (2008-10-07). "Sudilusių pinigų reinkarnacija". Lietuvos rytas (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 2010-11-30.

General

- Kurt Schuler; George Selgin & Joseph Sinkey, Jr. (1991-10-28). "Replacing the Ruble in Lithuania: Real Change versus Pseudoreform". Cato Policy Analysis (163). Archived from the original on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

Lithuanian talonas

| Preceded by:Soviet ruble Reason: introduction of temporary currencyRatio: 1 talonas = 1 or 10 rubles | Currency of Lithuania 1 May 1992 – 26 June 1993 | Succeeded by:Lithuanian litas Reason: introduction of permanent currencyRatio: 1 litas = 100 talonas |

|---|