Majorcan cartographic school (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Medieval naval group

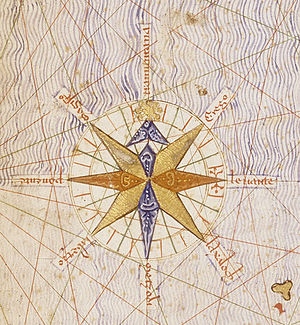

Detail of the Catalan Atlas, the first compass rose depicted on a map. Notice the Pole Star set on N.

"Majorcan cartographic school" is the term coined by historians to refer to the collection of predominantly Jewish cartographers, cosmographers and navigational instrument-makers and some Christian associates that flourished in Majorca in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries until the expulsion of the Jews. The label is usually inclusive of those who worked in Catalonia. The Majorcan school is frequently contrasted with the contemporary Italian cartography school.

The island of Majorca, the largest of the Balearic islands in the western Mediterranean, had a long history of seafaring. Muslim and Jewish merchants participated in extensive trade across the Mediterranean Sea with Italy, Egypt and Tunisia. In the 14th century their commerce entered into the Atlantic, reaching as far as England and the Low Countries. Ruled as an independent Muslim kingdom through much of the Early Middle Ages, Majorca came under Christian rule in 1231.

It retained its independence as the Kingdom of Majorca until 1344, when it was permanently annexed to the Crown of Aragon. This coincided with a period of Aragonese expansionism across the Mediterranean to Sardinia and Corsica, Sicily and Greece (Athens and Neopatria), in which Majorcan nautical, cartographic and mercantile expertise was often called upon. Majorcan merchants and seafarers spearheaded the attempt by the Aragonese crown to seize the newly discovered Canary Islands in the Atlantic from the 1340s to the 1360s.

Majorcan cosmographers and cartographers experimented and developed their own cartographic techniques. According to some scholars (e.g. Nordenskiold), the Majorcans were responsible for the invention (c. 1300) of the "normal portolan chart". The portolan was a realistic, detailed nautical chart, gridded by a rhumbline network with compass lines that could be used to deduce exact sailing directions between any two points.

Portolan charts, which appeared rather suddenly after 1300, constitute a sharp departure from all earlier maps. Unlike the circular mappa mundi of Christian academic tradition, the portolan was oriented towards the north, and focused on a realistic depiction of geographic distances with a degree of accuracy that is astounding, even by modern standards. Historians speculate that the portolan was constructed from the first-hand information of mariners and merchants, possibly assisted by astronomers, and were geared for navigational use, in particular the plotting by compass of navigational routes.

Both Majorca and Genoa have laid claim for the invention of the portolan chart, and it is unlikely this will ever be resolved. Few charts have survived to the modern day. The Carta Pisana portolan chart, made at the end of the 13th century (1275–1300), is the oldest surviving nautical chart.[1] The earliest extant ones, from the first half of the 14th century, seem to have been constructed by Genoese cartographers, with Majorcan charts making their appearance only in the latter half of the century. As a result, many historians have argued that the Majorcan cartography derived from the Genoese, citing the mysterious figure of Angelino Dulcert, possibly a Genoese immigrant working in Majorca in the 1330s, as the key intermediary in the transmission.[2]

On the other hand, some scholars have embraced the hypothesis first forwarded by A.E. Nordenskiöld, that the surviving charts are misleading, that the earliest Genoese maps were just faithful copies of a conjectured prototype, now lost, composed around 1300 by an unknown Majorcan cosmographer, possibly with the involvement of Ramon Llull.[3] An intermediary position acknowledges Genoese priority, but insists the Majorcan school had an autonomous origin, at best "inspired", but not derived, from the Genoese.[4] Recent research tends to lean towards the first interpretation, but at the same time curbing some of the more extreme Italian claims and recognizing distinctively Majorcan development.[5]

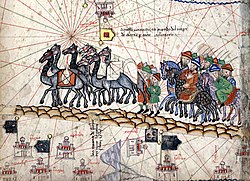

A part of the Catalan Atlas that was created by Majorca's cartographer Abraham Cresques in 1375

Regardless of the exact origin, historians agree that the Majorcans developed their own distinctive style or "school" of portolan cartography, which can be distinguished from the "Italian school". Both Italian and Majorcan portolan charts focus on the same geographic area, what is sometimes called the "Normal Portolan": the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea and the Atlantic Ocean coast up to the environs of Flanders - the area frequently travelled by contemporary Mediterranean merchants and sailors.

As time and knowledge progressed, some cartographers stretched the geographic boundaries of the normal portolan to include a larger swathe of Atlantic ocean, including many Atlantic islands, real and mythical, a longer stretch of the west African coast to the south, the Baltic Sea in the north and the Caspian Sea in the east. The central focus on the Mediterranean remained throughout and the scale rarely changed.

The distinction between the Majorcan and Italian school is one of style rather than range. Italian portolan charts were sparse and restrained, strictly focused on coastal detail, with the inland areas left largely or wholly empty, and the charts largely bereft of illustrations.

The Majorcan style, its beginnings already decipherable in the 1339 chart of Angelino Dulcert, and finding its epitome in the Catalan Atlas of 1375, attributed to Majorcan cartographer Abraham Cresques, contained a lot more inland detail and was replete with rich colorful illustrations, depicting cities, mountain ranges, rivers and some miniature people. Among the quintessential features replicated in almost all Majorcan charts:

- scattered notes and labels in Catalan

- the Red Sea painted red

- the Atlas Mountains depicted as a palm tree

- the Alps as a chicken's foot

- the Tagus as a shepherd's crook, with the curve wrapping around Toledo.

- the Danube as a chain of links or hillocks.

- Bohemia as a horseshoe

- the Canary island of Lanzarote colored with a Genoese shield (red cross on white).

- the island of Rhodes also colored with a shield with a cross.

- the striped shield of the Crown of Aragon replicated as often as possible, including covering the island of Majorca itself.

- a compass rose somewhere on the map, with the Pole Star set on the north.[6]

Among the miniature people routinely found in many Majorcan maps are depictions of the traders on the Silk Road and the trans-Saharan route, the Emperor of Mali seated on a gold mine and the ship of Jaume Ferrer.

Although the Italian school largely adhered to its sparse style, some later Italian cartographers, such as the Pizzigani brothers and Battista Beccario toyed with Majorcan themes, and introduced some of their features into their own maps.

Although some historians like to distinguish the Italian maps as "nautical" and the Majorcan maps as "nautico-geographic", it is important to note that the Majorcan portolans did not sacrifice the essential nautical function of their portolans. Lift the entertaining illustrations, and the Majorcan maps are as nautically detailed and serviceable as the Italian.

Major members of the Majorcan school of cartography include:

- Angelino Dulcert (fl. 1339) - possibly a Genoese immigrant.

- Abraham Cresques (fl. 1375)

- Jehuda Cresques ("Jaume Riba"/"Jacobus Ribes")

- Haym ibn Risch ("Joan de Vallsecha")

- Guillem Soler (fl. 1380s)

- Mecia de Viladestes (fl. 1410s)

- Jacomé of Majorca (1420s?) - moved to Portugal

- Gabriel de Vallseca (fl.1430s-40s)

- Pere Rosell (fl.1460s)

- Jaume Bertran (fl. 1480s).

Unlike in Italy, where the crafts of instrument-making and cartography were distinct, most of the Majorcan cartographers also worked as makers of nautical instruments - often appearing in civic records, as both master map-maker and bruixoler ("compass-maker"). Some were also amateur or professional cosmographers, with expertise in astrology and astronomy, frequently inserting astronomical calendars in their atlases.

Most members of the Majorcan school, with the exception of Soler, were Jews, whether practicing or conversos. As a result, the school suffered heavily and eventually expired with the extension of force-conversion, expulsions and the Spanish Inquisition into the realms of the Crown of Aragon in the late 15th century.

The production of medieval Portolan charts can be divided in two major schools: the Italian and the Catalan. Italian medieval cartographers came mostly from Genoa and Venice. Catalan charts were made in Majorca and Barcelona. Beside these two major schools, some maps were made in Portugal, but no examples survive.[7]

The inhabitants of Majorca were great navigators and cartographers. Their geographical knowledge was earned from their own experience and developed in a multicultural atmosphere. Muslim and Jewish merchants participated in extensive trade with Egypt and Tunisia, and in the 14th century they started doing business with England and Netherlands. These groups were not limited by the rules imposed by the Christian framework, and their maps were way ahead of their time. Professor Gerald Crone, who wrote books on medieval mapping, said of these cartographers, they "...threw off the bounds of tradition and anticipated the achievements of the Renaissance". The maps they made were prized by the princes and rulers of the Spanish mainland and other countries. The maps made in Majorca were easy to recognize by their brightly colored illustrations of significant geographical features and portraits of foreign rulers.[8]

The first known Majorcan map was made by Angelino Dulcert in 1339.[7] Even in this early work, all the distinguishing features of the Majorcan Cartographic School were present. Dulcert made precise, colorful drawings that showed all the topographical details including rivers, lakes, mountains, etc. The notes written in Latin described the map.[9]

The most famous cartographers from the Majorcan school were Jews.[10]

Catalan Atlas and Abraham and Jehuda Cresques

[edit]

Marco Polo's caravan from the Catalan Atlas

Abraham Cresques also known as, Cresques the Jew, was appointed as a Master of Maps and Compasses by John I of Aragon. The money he got for his appointment was used to build baths for Jews in Palma. In 1374 and 1375 Abraham and his son Jehuda worked on a special order. John I of Aragon advised the authorities that he needed to get a map, which would show the Strait of Gibraltar, the Atlantic coast and the ocean itself. The map they made was named the Catalan Atlas, and it is the most important Catalan map of the medieval period.[10][11]

The first two leaves, forming the oriental portion of the Catalan Atlas, illustrate numerous religious references as well as a synthesis of medieval mappae mundi (Jerusalem located close to the center) and the travel literature of the time, notably Marco Polo's Book of Marvels and the Travels, and Voyage of Sir John Mandeville. Many Indian and Chinese cities can be identified. The explanatory texts report customs described by Marco Polo.[9] Cresques, who knew Arabic, also used the travel narratives of Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta. Mecca has a blue dome and shows Muslim prayer. The text next to the image is:

In this town is the shrine of Mohammed the Prophet of the Saracens, who come here on pilgrimages from every country. And they say that, having seen something so precious, they are no longer worthy of seeing anything more at all, and they blind themselves in honor of Mohammed."[8][12]

While the areas under Muslim control were marked with domes, Jerusalem was surrounded by tales from Old and New Testaments like the Garden of Eden, the crucifixion, Noah's Ark and others.

The image of the caravan is accompanied by Marco Polo's travel account:

You must know that those who wish to cross this desert remain and lodge for one whole week in a town named Lop, where they and their beasts can rest. Then they lay in all the provisions they need for seven months.[13]

A Catalan Atlas was requested by Charles V of France, even though he expelled all the Jews from France in 1394.

The Catalan Atlas is located now in Bibliothèque nationale de France. A few other Cresques maps were mentioned in inventories from Spain and France in late 1387.[10][11]

Jehuda Cresques continued his father's traditions. He was forced to convert to Christianity in 1391. His new name was Jacobus Ribes. He was called "lo Jueu buscoler" (the map Jew), or "el jueu de les bruixoles" (the compass Jew). Jehuda was ordered to move to Barcelona, where he continued his work, as a court cartographer. Later, he was invited to Portugal by Henry the Navigator. His maps were still made in Catalan (Majorca) traditions, and that's why he was called "Mestre Jacome de Malhorca".[10] He was the first director of famous Nautical observatory at Sagres at the age of discovery.[10]

Other Jewish cartographers

[edit]

Another famous Jewish cartographer was Haym ibn Risch. He was forced to convert to Christianity and took the name Juan de Vallsecha. He was probably the father of Gabriel de Vallseca, author of yet another famous mapamundi, one later used by Amerigo Vespucci. Gabriel also produced a very accurate maps of Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea.[14][15] Another Jewish cartographer was Mecia de Vildestes. An outstanding map by Vildestes dated 1413 is proudly featured at the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris.

Anti-Jewish persecutions brought the end to the famous school of cartography at Majorca.[10]

Chronology of Majorcan cartographers

[edit]

(Timeline derived from ca:Llista cronològica de cartògrafs portolans mallorquins)

- ^ Aczel, Amir D. (2001). The riddle of the compass: the invention that changed the world. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-15-600753-5. carta pisana.

- ^ e.g. Caraci, 1959. More extreme claims were articulated earlier by Magnaghi (1909), who attempts to appropriate not only Dulcert, but Soler, Rosell and others, into the Italian pantheon.

- ^ Nordenskiöld (1896, 1897).

- ^ Winter (1958).

- ^ e.g. Pujades (2007); Campbell (1987; 2011)

- ^ Later Italian school maps began to include a compass rose, but placed a circumflex "hat" (^) as the northmark. Portuguese maps (from 1504) used a fleur-de-lis as the northmark. See Winter (1947:p.25)

- ^ a b Leo Bagrow, and R. A. Skelton (1964). History of Cartography. Watts. p. 65,66. ISBN 9781412825184. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ a b "Newberry Library". Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ a b "The Majorcan Cartographic School". 1964. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ a b c d e f Cecil Roth (1940). The Jewish Contribution To Civilization. Harper. pp. 69–72. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ a b Clayton J. Drees (November 30, 2000). The Late Medieval Age of Crisis and Renewal, 1300-1500: A Biographical Dictionary (The Great Cultural Eras of the Western World). Greenwood. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0-313-30588-9. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ "The Catalan Atlas". Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ "The Catalan Atlas". Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ B. Barry Levy (1990). Planets, Potions, and Parchments: Scientifica Hebraica from the Dead Sea Scrolls to the Eighteenth Century. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-0-7735-0791-3. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ Julia Brauch; Anna Lipphardt; Alexandra Nocke (2008). Jewish topographies: visions of space, traditions of place. p. 185. ISBN 9780754671183. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- www.cresquesproject.net—Translation in English of the works of Riera i Sans and Gabriel Llompart on the Jewish Majorcan Map-makers of the Late Middle Ages

- Portolan charts from S.XIII to S.XVI - Additions, Corrections, Updates

- Campbell, T. (1987) "Portolan Charts from the Late Thirteenth Century to 1500". The History of Cartography. Volume 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 371–463.

- Campbell, T. (2011) "A critical re-examination of early portolan charts with a reassessment of their replication and seaboard function" (online)

- Caraci, G. (1959) Italiani e Catalani nella primitiva cartografia medievale, Rome: 'Universita degli studi.

- Magnaghi, A. (1909) "Sulle origini del portolano normale nel Medio Evo e della Cartografia dell'Europa occidentale", in Memorie geografiche, vol. 4, no.8, p. 115-80.

- Nordenskiöld, Adolf Erik (1896) "Résumé of an Essay on the Early History of Charts and Sailing Directions", Report of the Sixth International Geographical Congress: held in London, 1895. London: J. Murray p.685-94

- Nordenskiöld, Adolf Erik (1897) Periplus: An Essay on the Early History of Charts and Sailing Directions, tr. Frances A. Bather, Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Pujades i Bataller, Ramon J. (2007) Les cartes portolanes: la representació medieval d'una mar solcada. Barcelona

- Heinrich Winter (1947) "On the Real and the Pseudo-Pilestrina Maps and Other Early Portuguese Maps in Munich", Imago Mundi, vol. 4,p. 25-27.

- Winter, Heinrich (1958) "Catalan Portolan Maps and their place in the total view of cartographic development", Imago Mundi, Vol.11, p. 1-12