Mars landing (original) (raw)

Landing of a spacecraft on the surface of Mars

Animation of a Mars landing touchdown, the InSight lander in 2018

A Mars landing is a landing of a spacecraft on the surface of Mars. Of multiple attempted Mars landings by robotic, uncrewed spacecraft, ten have had successful soft landings. There have also been studies for a possible human mission to Mars including a landing, but none have been attempted.

As of 2023, the Soviet Union, United States and China have conducted Mars landings successfully.[1] Soviet Mars 3, which landed in 1971, was the first successful Mars landing, though the spacecraft failed after 110 seconds on the surface. All other Soviet Mars landing attempts failed.[2] Viking 1 and Viking 2 were first successful NASA landers, launched in 1975. NASA's Mars Pathfinder, launched in 1996, successfully delivered the first Mars rover, Sojourner. In 2021, first Chinese lander and rover, Tianwen 1, successfully landed on Mars.

Methods of descent and landing

[edit]

As of 2021, all methods of landing on Mars have used an aeroshell and parachute sequence for Mars atmospheric entry and descent, but after the parachute is detached, there are three options. A stationary lander can drop from the parachute back shell and ride retrorockets all the way down, but a rover cannot be burdened with rockets that serve no purpose after touchdown.[_citation needed_]

One method for lighter rovers is to enclose the rover in a tetrahedral structure which in turn is enclosed in airbags. After the aeroshell drops off, the tetrahedron is lowered clear of the parachute back shell on a tether so that the airbags can inflate. Retrorockets on the back shell can slow descent. When it nears the ground, the tetrahedron is released to drop to the ground, using the airbags as shock absorbers. When it has come to rest, the tetrahedron opens to expose the rover.[_citation needed_]

If a rover is too heavy to use airbags, the retrorockets can be mounted on a sky crane. The sky crane drops from the parachute back shell and, as it nears the ground, the rover is lowered on a tether. When the rover touches ground, it cuts the tether so that the sky crane (with its rockets still firing) will crash well away from the rover. Both Curiosity and Perseverance used sky crane for landing.[3]

Landing in an airbag

An illustration of Perseverance tethered to the sky crane

The MSL Descent Stage under construction on Earth

Ingenuity helicopter executing a vertical takeoff and landing

Descent of heavier payloads

[edit]

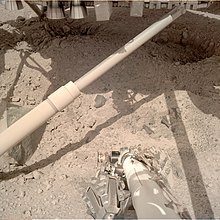

The thrusters of the InSight lander dug pits during landing beneath it at its landing site.

For landers that are even heavier than the Curiosity rover (which required a 4.5 meter (15 feet) diameter aeroshell), engineers are developing a combination rigid-inflatable Low-Density Supersonic Decelerator that could be 8 meters (26 feet) in diameter. It would have to be accompanied by a proportionately larger parachute.[4]

Landing robotic spacecraft, and possibly some day humans, on Mars is a technological challenge. For a favorable landing, the lander module has to address these issues:[5][6]

- Thinness of Mars's atmosphere

- Measurement of distance to surface

- Inadequate technology for ballistic aerocapture

- Inadequate technology for retropropulsive powered descent

- Inadequate mission designs

- Shorter time to perform entry, descent and landing (EDL)

In 2018, NASA successfully landed the InSight lander on the surface of Mars, re-using Viking-era technology.[7] But this technology cannot afford the ability to land large number of cargoes, habitats, ascent vehicles and humans in case of crewed Mars missions in near future. In order to improve and accomplish this intent, there is need to upgrade technologies and launch vehicles. Some of the criteria for a lander performing a successful soft-landing using current technology are as follows:[8][5]

Lander requirements

| Feature | Criterion |

|---|---|

| Mass | Less than 0.6 tonnes (1,300 lb) |

| Ballistic coefficient | Less than 35 kg/m2 (7.2 lb/sq ft) |

| Diameter of aeroshell | Less than 4.6 m (15 ft) |

| Geometry of aeroshell | 70° spherical cone shell |

| Diameter of parachute | Less than 30 m (98 ft) |

| Descent | Supersonic retropropulsive powered descent |

| Entry | Orbital entry (i.e. entry from Mars orbit) |

Communicating with Earth

[edit]

Beginning with the Viking program,[a] all landers on the surface of Mars have used orbiting spacecraft as communications satellites for relaying their data to Earth. The landers use UHF transmitters to send their data to the orbiters, which then relay the data to Earth using either X band or Ka band frequencies. These higher frequencies, along with more powerful transmitters and larger parabolic reflectors, permit the orbiters to send the data much faster than the landers could manage transmitting directly to Earth, which conserves valuable time on the receiving antennas.[9]

List of Mars landings

[edit]

Insight Mars lander view in December 2018

In the 1970s, several USSR probes unsuccessfully tried to land on Mars. Mars 3 landed successfully in 1971 but failed soon afterwards. But the American Viking landers made it to the surface and provided several years of images and data. However, the next successful Mars landing was not until 1997, when Mars Pathfinder landed.[10] In the 21st century there have been several successful landings, but there have also been many crashes.[10]

The first probe intended to be a Mars impact lander was the Soviet Mars 1962B, unsuccessfully launched in 1962.[11]

In 1970 the Soviet Union began the design of Mars 4NM and Mars 5NM missions with super-heavy uncrewed Martian spacecraft. First was Marsokhod, with a planned date of early 1973, and second was the Mars sample return mission planned for 1975. Both spacecraft were intended to be launched on the N1 rocket, but this rocket never flew successfully and the Mars 4NM and Mars 5NM projects were cancelled.[12]

In 1971 the Soviet Union sent probes Mars 2 and Mars 3, each carrying a lander, as part of the Mars probe program M-71. The Mars 2 lander failed to land and impacted Mars. The Mars 3 lander became the first probe to successfully soft-land on Mars, but its data-gathering had less success. The lander began transmitting to the Mars 3 orbiter 90 seconds after landing, but after 14.5 seconds, transmission ceased for unknown reasons. The cause of the failure may have been related to the extremely powerful Martian dust storm taking place at the time. These space probes each contained a Mars rover, PrOP-M, although they were never deployed.

In 1973, the Soviet Union sent two more landers to Mars, Mars 6 and Mars 7. The Mars 6 lander transmitted data during descent but failed upon impact. The Mars 7 probe separated prematurely from the carrying vehicle due to a problem in the operation of one of the onboard systems (attitude control or retro-rockets) and missed the planet by 1,300 km (810 mi).

The double-launching Mars 5M (Mars-79) sample return mission was planned for 1979, but was cancelled due to complexity and technical problems.[_citation needed_]

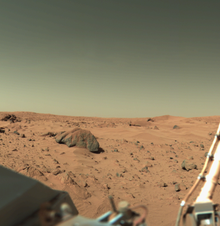

Viking 1 landing site (click image for detailed description).

In 1976 two American Viking probes entered orbit about Mars and each released a lander module that made a successful soft landing on the planet's surface. They subsequently had the first successful transmission of large volumes of data, including the first color pictures and extensive scientific information. Measured temperatures at the landing sites ranged from 150 to 250 K (−123 to −23 °C; −190 to −10 °F), with a variation over a given day of 35 to 50 °C (95 to 122 °F).[_citation needed_] Seasonal dust storms, pressure changes, and movement of atmospheric gases between the polar caps were observed.[_citation needed_] A biology experiment produced possible evidence of life, but it was not corroborated by other on-board experiments.[_citation needed_]

While searching for a suitable landing spot for Viking 2's lander, the Viking 1 orbiter photographed the landform that constitutes the so-called "Face on Mars" on 25 July 1976.

The Viking program was a descendant of the cancelled Voyager program, whose name was later reused for a pair of outer solar system probes.

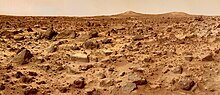

"Ares Vallis" as photographed by Mars Pathfinder

NASA's Mars Pathfinder spacecraft, with assistance from the Mars Global Surveyor orbiter, landed on 4 July 1997. Its landing site was an ancient flood plain in Mars' northern hemisphere called Ares Vallis, which is among the rockiest parts of Mars. It carried a tiny remote-controlled rover called Sojourner, the first successful Mars rover, that traveled a few meters around the landing site, exploring the conditions and sampling rocks around it. Newspapers around the world carried images of the lander dispatching the rover to explore the surface of Mars in a way never achieved before.

Until the final data transmission on 27 September 1997, Mars Pathfinder returned 16,500 images from the lander and 550 images from the rover, as well as more than 15 chemical analyses of rocks and soil and extensive data on winds and other weather factors. Findings from the investigations carried out by scientific instruments on both the lander and the rover suggest that in the past Mars has been warm and wet, with liquid water and a thicker atmosphere. The mission website was the most heavily trafficked up to that time.

Conceptual drawing of the Mars Polar Lander on the surface of Mars.

Mars Spacecraft 1988–1999

| Spacecraft | Evaluation | Had or was Lander |

|---|---|---|

| Phobos 1 | No | For Phobos |

| Phobos 2 | Yes | For Phobos |

| Mars Observer | No | No |

| Mars 96 | No | Yes |

| Mars Pathfinder | Yes | Yes |

| Mars Global Surveyor | Yes | No |

| Mars Climate Orbiter | No | No |

| Mars Polar Lander | No | Yes |

| Deep Space 2 | No | Yes |

| Nozomi | No | No |

Mars 96, an orbiter launched on 16 November 1996 by Russia, failed when the planned second burn of the Block D-2 fourth stage did not occur. Following the success of Global Surveyor and Pathfinder, another spate of failures occurred in 1998 and 1999, with the Japanese Nozomi orbiter and NASA's Mars Climate Orbiter, Mars Polar Lander, and Deep Space 2 penetrators all suffering various terminal errors. Mars Climate Orbiter is infamous for Lockheed Martin engineers mixing up the usage of U.S. customary units with metric units, causing the orbiter to burn up while entering Mars's atmosphere. Out of 5–6 NASA missions in the 1990s, only 2 worked: Mars Pathfinder and Mars Global Surveyor, making Mars Pathfinder and its rover the only successful Mars landing in the 1990s.

Mars Express and Beagle 2

[edit]

On 2 June 2003, the European Space Agency's Mars Express set off from Baikonur Cosmodrome to Mars. The Mars Express craft consisted of the Mars Express Orbiter and the lander Beagle 2. Although the landing probe was not designed to move, it carried a digging device and the least massive spectrometer created to date, as well as a range of other devices, on a robotic arm in order to accurately analyse soil beneath the dusty surface.

The orbiter entered Mars orbit on 25 December 2003, and Beagle 2 should have entered Mars' atmosphere the same day. However, attempts to contact the lander failed. Communications attempts continued throughout January, but Beagle 2 was declared lost in mid-February, and a joint inquiry was launched by the UK and ESA that blamed principal investigator Colin Pillinger's poor project management. Nevertheless, Mars Express Orbiter confirmed the presence of water ice and carbon dioxide ice at the planet's south pole. NASA had previously confirmed their presence at the north pole of Mars.[_citation needed_]

Signs of the Beagle 2 lander were found in 2013 by the HiRISE camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and the Beagle 2's presence was confirmed in January 2015, several months after Pillinger's death. The lander appears to have successfully landed but not deployed all of its power and communications panels.

Mars Exploration Rovers

[edit]

Shortly after the launch of Mars Express, NASA sent a pair of twin rovers toward the planet as part of the Mars Exploration Rover mission. On 10 June 2003, NASA's MER-A (Spirit) Mars Exploration Rover was launched. It successfully landed in Gusev Crater (believed once to have been a crater lake) on 3 January 2004. It examined rock and soil for evidence of the area's history of water. On 7 July 2003, a second rover, MER-B (Opportunity) was launched. It landed on 24 January 2004 in Meridiani Planum (where there are large deposits of hematite, indicating the presence of past water) to carry out similar geological work.

Despite a temporary loss of communication with the Spirit rover (caused by a file system anomaly[13]) delaying exploration for several days, both rovers eventually began exploring their landing sites. The rover Opportunity landed in a particularly interesting spot, a crater with bedrock outcroppings. In fast succession, mission team members announced on 2 March that data returned from the rover showed that these rocks were once "drenched in water", and on 23 March that it was concluded that they were laid down underwater in a salty sea. This represented the first strong direct evidence for liquid water on Mars at some time in the past.

Towards the end of July 2005, it was reported by the Sunday Times that the rovers may have carried the bacteria Bacillus safensis to Mars. According to one NASA microbiologist, this bacteria could survive both the trip and conditions on Mars. Despite efforts to sterilise both landers, neither could be assured to be completely sterile.[14]

Having been designed for only three-month missions, both rovers lasted much longer than planned. Spirit lost contact with Earth in March 2010, 74 months after commencing exploration. Opportunity, however, continued to carry out surveys of the planet, surpassing 45 km (28 mi) on its odometer by the time communication with it was lost in June 2018, 173 months after it began.[15][16] These rovers have discovered many new things, including Heat Shield Rock, the first meteorite to be discovered on another planet.

Here is some debris from a Mars landing, as viewed by a Rover. This shows the area around a heat shield and resulting shield impact crater. The heat shield was jettisoned during the descent, impacting the surface on its own trajectory, while the spacecraft went on to land the rover.

Camera on Mars orbiter snaps Phoenix suspended from its parachute during descent through Mars' atmosphere.

Phoenix launched on 4 August 2007, and touched down on the northern polar region of Mars on 25 May 2008. It is famous for having been successfully photographed while landing, since this was the first time one spacecraft captured the landing of another spacecraft onto a planet.[17]

Mars Science Laboratory

[edit]

Mars Science Laboratory (and the Curiosity rover) descending on Mars

The Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) (and Curiosity rover), launched in November 2011, landed in a location that is now called "Bradbury Landing", on Aeolis Palus, between Peace Vallis and Aeolis Mons ("Mount Sharp"), in Gale Crater on Mars on 6 August 2012, 05:17 UTC.[18][19] The landing site was in Quad 51 ("Yellowknife")[20][21][22][23] of Aeolis Palus near the base of Aeolis Mons. The landing site[24] was less than 2.4 km (1.5 mi) from the center of the rover's planned target site after a 563,000,000 km (350,000,000 mi) journey.[25] NASA named the landing site "Bradbury Landing", in honor of author Ray Bradbury, on 22 August 2012.[24]

ExoMars Schiaparelli

[edit]

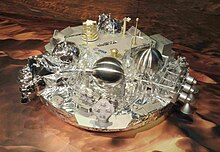

Model of Schiaparelli lander at ESOC

The Schiaparelli lander was intended to test technology for future soft landings on the surface of Mars as part of the ExoMars project. It was built in Italy by the European Space Agency (ESA) and Roscosmos. It was launched together with the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) on 14 March 2016 and attempted a landing on 19 October 2016. Telemetry was lost about one minute before the scheduled landing time,[26] but confirmed that most elements of the landing plan, including heat shield operation, parachute deployment, and rocket activation, had been successful.[27] The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter later captured imagery showing what appears to be Schiaparelli's crash site.[28]

Phoenix landing art, similar to Insight

NASA's InSight lander_,_ designed to study seismology and heat flow from the deep interior of Mars, was launched on 5 May 2018. It landed successfully in Mars's Elysium Planitia on 26 November 2018.[29]

Mars 2020 and Tianwen-1

[edit]

NASA's Mars 2020 and CNSA's Tianwen-1 were both launched in the July 2020 window. Mars 2020's rover Perseverance successfully landed, in a location that is now called "Octavia E. Butler Landing", in Jezero Crater on 18 February 2021,[30] Ingenuity helicopter was deployed and took subsequent flights in April.[31] _Tianwen_-1's lander and Zhurong rover landed in Utopia Planitia on 14 May 2021 with the rover being deployed on 22 May 2021 and dropping a remote selfie camera on 1 June 2021.[32]

The ESA Rosalind Franklin is planned for launch in the late 2020s and would obtain soil samples from up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) depth and make an extensive search for biosignatures and biomolecules. There is also a proposal for a Mars Sample Return Mission by ESA and NASA, which would launch in 2024 or later. This mission would be part of the European Aurora Programme.[_citation needed_]

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has proposed to include landing of a rover and Marsplane in its Mars Lander Mission around 2030 near Eridania basin.[33]

Landing site identification

[edit]

As a Mars lander approaches the surface, identifying a safe landing spot is a concern.[34]

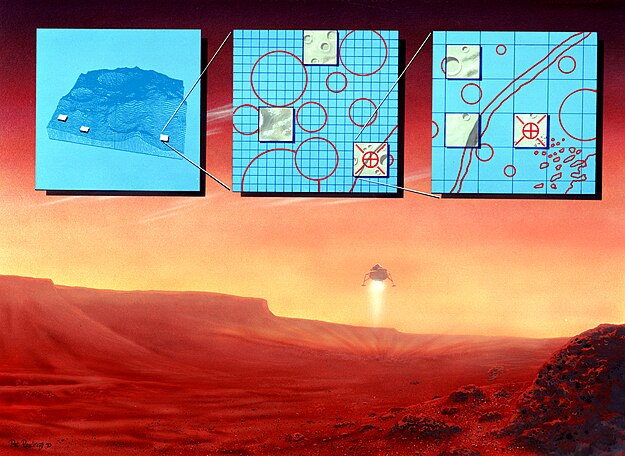

The inset frames show how the lander's descent imaging system is identifying hazards (NASA, 1990)

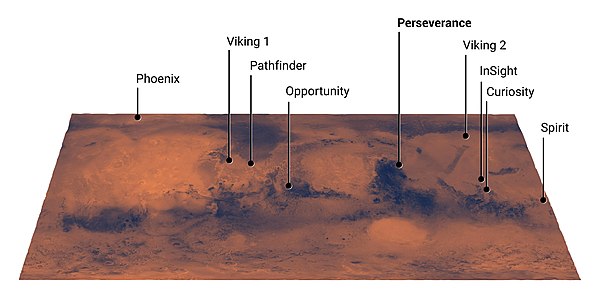

Mars Landing Sites (16 December 2020]

Twinned locations to Mars Landing sites on Earth

[edit]

In the run-up to NASA’s Mars 2020 landing, former planetary scientist and film-maker Christopher Riley mapped the locations of all eight of NASA's successful Mars landing sites onto their equivalent spots on Earth, in terms of latitudes and longitudes; presenting pairs of photographs from each twinned interplanetary location on Earth and Mars to draw attention to climate change.[35] Following the successful landing of NASA's Perseverance Rover on February 18, 2021, Riley called for volunteers to travel to and photograph its twinned Earth location in Andegaon Wadi, Sawali, in the central Indian state of Maharashtra (18.445°N, 77.451°E).[36][37][38] Eventually BBC World Service radio programme Digital Planet listener Gowri Abhiram, from Hyderabad took up the challenge, and travelled there on the 22nd January 2022, becoming the first person to knowingly reach a spot on Earth that matches the latitude and longitude of a robotic presence on the surface of another world.[39] China's Tianwen-1 landing site maps onto an area in Southern China, 40 kilometres Southwest of Guilin and is yet to be photographed for the project.[37]

- Colonization of Mars

- Exploration of Mars

- Google Mars

- Human mission to Mars

- List of missions to Mars

- Mars race

- Mars rover

- Space weather

^ The last Viking lander reverted to Earth-direct communications after both orbiters expired.

^ mars.nasa.gov. "Historical Log | Missions". NASA Mars Exploration. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

^ Heil, Andy (2 August 2020). "The Soviet Mars Shot That Almost Everyone Forgot". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

^ Reichhardt, Tony (August 2007). "Legs, bags or wheels?". Air & Space. Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

^ "Low-Density Supersonic Decelerator (LDSD)" (PDF). Press kit. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. May 2014.

^ a b Braun, Robert D.; Manning, Robert M. (2007). "Mars Exploration Entry, Descent, and Landing Challenges". Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. 44 (2): 310–323. Bibcode:2007JSpRo..44..310B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.463.8773. doi:10.2514/1.25116.

^ Wells, G. W., Lafleur, J. M., Verges, A., Manyapu, K., Christian III, J. A., Lewis, C., & Braun, R. D. (2006). Entry descent and landing challenges of human Mars exploration.

^ mars.nasa.gov. "Entry, Descent, and Landing | Landing". NASA's InSight Mars Lander. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

^ M, Malaya Kumar Biswal; A, Ramesh Naidu (23 August 2018). "A Novel Entry, Descent and Landing Architecture for Mars Landers". arXiv:1809.00062 [physics.pop-ph].

^ "Talking to Martians: Communications with Mars Curiosity Rover". Steven Gordon's Home Page. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

^ a b February 2021, Elizabeth Howell 08 (8 February 2021). "A Brief History of Mars Missions". Space.com.

{{[cite web](/wiki/Template:Cite%5Fweb "Template:Cite web")}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)^ "NASA A Chronology of Mars Exploration". Retrieved 28 March 2007.

^ "Советский грунт с Марса". Archived from the original on 16 April 2008.

^ http://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/fall11/cos109/mars.rover.pdf [_bare URL PDF_]

^ "It's one small step for a bug, a giant red face for NASA". London: The Sunday Times (UK). 17 July 2005. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 17 June 2006.

^ Staff (7 June 2013). "Opportunity's Mission Manager Reports August 19, 2014". NASA. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

^ "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: All Opportunity Updates". mars.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

^ "Phoenix Makes a Grand Entrance". NASA. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

^ Wall, Mike (6 August 2012). "Touchdown! Huge NASA Rover Lands on Mars". Space.com. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

^ NASA Staff (2012). "Mars Science Laboratory – PARTICIPATE – Follow Your CURIOSITY". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

^ NASA Staff (10 August 2012). "Curiosity's Quad – IMAGE". NASA. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

^ Agle, DC; Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (9 August 2012). "NASA's Curiosity Beams Back a Color 360 of Gale Crate". NASA. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

^ Amos, Jonathan (9 August 2012). "Mars rover makes first colour panorama". BBC News. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

^ Halvorson, Todd (9 August 2012). "Quad 51: Name of Mars base evokes rich parallels on Earth". USA Today. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

^ a b Brown, Dwayne; Cole, Steve; Webster, Guy; Agle, D.C. (22 August 2012). "NASA Mars Rover Begins Driving at Bradbury Landing". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

^ "Impressive' Curiosity landing only 1.5 miles off, NASA says". Retrieved 10 August 2012.

^ "ExoMars TGO reaches Mars orbit while EDM situation under assessment". European Space Agency. 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

^ "ESA - Robotic Exploration of Mars - ExoMars 2016 - Schiaparelli Anomaly Inquiry". exploration.esa.int.

^ Chang, Kenneth (21 October 2016). "Dark spot in Mars photo is probably wreckage of European spacecraft". New York Times. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

^ "NASA InSight Lander Arrives on Martian Surface". NASA’s Mars Exploration Program. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

^ "Touchdown! NASA's Mars Perseverance Rover Safely Lands on Red Planet". NASA’s Mars Exploration Program.

^ Witze, Alexandra (19 April 2021). "Lift off! First flight on Mars launches new way to explore worlds". Nature. 592 (7856): 668–669. Bibcode:2021Natur.592..668W. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00909-z. PMID 33875875. S2CID 233308286.

^ Amos, Jonathan (15 May 2021). "China lands its Zhurong rover on Mars". BBC News. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

^ Neeraj Srivastava; S. Vijayan; Amit Basu Sarbadhikari (27 September 2022), "Future Exploration of the Inner Solar System: Scope and the Focus Areas", Planetary Sciences Division (PSDN), Physical Research Laboratory – via ISRO Facebook Panel Discussion, Mars Orbiter Mission National Meet

^ "Worlds Apart: Medium". 13 February 2022.

^ "BBC World Service - Digital Planet, Comparing the landscape of Mars to Earth". BBC (Podcast). Retrieved 20 February 2021.

^ a b "The Naked Scientists Podcast, Q&A: Mars, Mental-Health and Managing Bitcoin". University of Cambridge (Podcast). Retrieved 20 February 2021.

^ "Astronomers Without Borders: Worlds Apart". YouTube. 16 April 2021. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021.

^ Riley, Christopher (13 February 2021). "From Mars to Earth". Medium. Retrieved 22 April 2022.