Masiakasaurus (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Noasaurid theropod dinosaur genus from the Late Cretaceous period

| _Masiakasaurus_Temporal range: Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) 72.1–66 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N | |

|---|---|

|

|

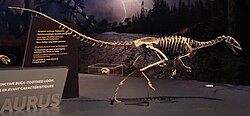

| Reconstructed skeleton, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Abelisauria |

| Family: | †Noasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Noasaurinae |

| Genus: | †_Masiakasaurus_Sampson et al., 2001 |

| Species: | †_M. knopfleri_ |

| Binomial name | |

| **†Masiakasaurus knopfleri**Sampson et al., 2001 |

Masiakasaurus is a genus of small predatory noasaurid theropod dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. In Malagasy, masiaka means "vicious"; thus, the genus name means "vicious lizard". The type species, Masiakasaurus knopfleri, was named after the musician Mark Knopfler, whose music inspired the expedition crew. It was named in 2001 by Scott D. Sampson, Matthew Carrano, and Catherine A. Forster. Unlike most theropods, the front teeth of M. knopfleri projected forward instead of straight down. This unique dentition suggests that they had a specialized diet, perhaps including fish and other small prey. Other bones of the skeleton indicate that Masiakasaurus were bipedal, with much shorter forelimbs than hindlimbs. M. knopfleri was a small theropod, reaching 1.8–2.1 m (5.9–6.9 ft) long and weighing 20 kg (44 lb).[1][2][3]

Masiakasaurus lived from 72.1 to 66 million years ago, along with animals such as Majungasaurus, Rapetosaurus, and Rahonavis. Masiakasaurus was a member of the group Noasauridae, small predatory ceratosaurs found primarily in South America.

Specimen FMNH PR 2481

Remains of Masiakasaurus have been found in the Late Cretaceous Maevarano Formation in northwestern Madagascar and were first described in the journal Nature in 2001. Fragmentary bones comprising around 40% of the skeleton were collected near the village of Berivotra. Several parts of the skull, including the distinctive teeth, were found. The humerus (upper arm bone), pubis, hindlimbs, and several vertebrae were also collected.[1]

Life Restoration

In 2011, additional specimens of Masiakasaurus were described. The braincase, premaxilla, facial bones, ribcage, portions of the hands and pectoral girdle (coracoid), and much of the cervical and dorsal vertebral column were described for the first time. The discovery of this new material clarified many aspects of noasaurid anatomy and made the genus among the best known dinosaurs.[4] The new finds did however not allow for a detailed study of its evolutionary relationships among ceratosaurs. With the new material, around 65% of the skeleton is currently known.[5]

Reconstructed skull, Field Museum of Natural History

The most distinctive characteristic of Masiakasaurus is the forward-projecting, or procumbent, front teeth. The teeth are heterodont, meaning that they have different shapes along the jaw.[1] The first four dentary teeth of the lower jaw project forward, with the first tooth angled only 10° above the horizontal. These teeth are long and spoon-shaped with hooked edges. They have carinae, or sharp edges, that are weakly serrated. Serrations are more evident along the rear edge the posterior teeth in the back of the jaw, which are also recurved and laterally compressed (flattened from the side), resembling the less unusual teeth of other carnivorous dinosaurs. The margin of the dentary curves downward so that the alveoli (tooth sockets) of the front teeth are directed forward. In fact, the alveolus of the first tooth is actually situated lower than the bottom edge of the rest of the lower jaw.[6] The lower part of the rear edge of the dentary has a long prong, known as a ventral process. This differs from the situation in abelisaurids, which have a much shorter ventral process. On the other hand, the upper part of the rear edge of the dentary is very similar to that of abelisaurids such as Majungasaurus and Carnotaurus. This part of the bone possesses an array of four small structures, three of which line a socket which connects to the surangular bone at the back of the lower jaw. Although the surangular bone is not preserved, several other bones of the lower jaw are, including a triangular angular bone, a gently curving prearticular bone, and a damaged yet notably concave articular bone. The angular and prearticular formed the lower edge of a large and rounded in the lower jaw (known as a mandibular fenestra) while the articular bone formed the lower part of the jaw joint. A long and tapering hyoid (tongue bone) has also been preserved.[5]The front teeth of the upper jaw are also procumbent, and the margin of the premaxilla curves slightly upward to direct them outward. Unlike the skulls of abelisaurids, which are very deep, the skull of Masiakasaurus is long and low. The lacrimal and postorbital bones around the eye are textured with bumpy projections. Not including the highly modified jaws and teeth, the skull of Masiakasaurus possesses many general ceratosaurian characteristics. Overall, its morphology is intermediate between abelisaurids and more basal ceratosaurs.[5]

The neck is relatively narrow in comparison to abelisaurids and bear stout neck ribs. While many theropods have s-shaped necks, the ribs would make the neck rather stiff in Masiakasaurus, and the back of the neck is positioned almost horizontally, giving it only a slighter curve. Like those of other abelisauroids, the vertebrae are heavily pneumaticized, or hollowed, and have relatively short neural spines. Pneumaticity is limited to the neck and foremost back vertebrae, however. Pneumatic cavities are also present in the braincase.[5]

As in other ceratosaurs, the shoulder blade (scapula) and shoulder girdle fuse into a single bone, the scapulocoracoid. This bone is very large and broad, even compared to the condition in other ceratosaurs. The scapula portion (above the glenoid, or arm socket) tapers towards the back while the coracoid portion (below the glenoid) is expanded into a curved blade-like structure. While abelisaurids have arms that are extremely reduced in size, Masiakasaurus and other noasaurids had longer forelimbs. The humerus is slender and known bones of the hand are relatively short. The related genus Noasaurus has a large and curved raptorial ungual (claw) which was originally interpreted as a sickle-like foot claw as in dromaeosaurids such as Velociraptor. More recently, this has been re-evaluated as a claw of the hand. The penultimate phalanx, the finger bone that immediately precedes the raptorial ungual in Noasaurus, is also known in Masiakasaurus and has a similar appearance. The enlarged ungual, however, is unknown in Masiakasaurus.[5] It is assumed that members of this genus had four fingers, with the middle two fingers being the longest as in other ceratosaurians.

Skeletal restoration showing remains of several specimens

In its initial 2001 description, Masiakasaurus was classified as a basal abelisauroid related to Laevisuchus and Noasaurus, two poorly known genera named in 1933 and 1980, respectively.[1] In the following year, Carrano et al. (2002) placed Masiakasaurus along with Laevisuchus and Noasaurus in the family Noasauridae. They conducted a phylogenetic analysis of abelisauroids using characteristics from Masiakasaurus. Below is a cladogram from an updated version of their analysis showing the phylogenetic placement of Masiakasaurus.[7]

Masiakasaurus scavenges a Rapetosaurus corpse

Carrano et al. (2002) distinguished two forms of Masiakasaurus, a robust form and a gracile form. The robust morph includes specimens with thicker bones and more pronounced projections for the attachment of ligaments and muscles. The gracile form includes specimens that are more slender and have less pronounced muscle attachments. It also has unfused tibiae, unlike the fused tibiae of the robust form. These two varieties may be an indication of sexual dimorphism in Masiakasaurus, but they may also represent two distinct populations.[6]

One specimen of Masiakasaurus, a right scapulocoracoid, bears holes that may be puncture marks from predation or scavenging. Majungasaurus, a large abelisaurid from the Maevarano Formation, may have preyed upon Masiakasaurus.[8] The holes may also have been the result of an infection.[5]

Skull diagram

The procument front teeth of Masiakasaurus were likely an adaptation for grasping small prey. They would have been unsuitable for tearing larger food apart. In the front of the jaws, carinae are restricted to the base of the teeth and would not have been used to tear prey. The back teeth, however, share the same general characteristics as those of most other theropods, suggesting that they served a similar function in Masiakasaurus such as cutting and slicing.[6]

Several feeding behaviors have been proposed for Masiakasaurus on the basis of its unusual dentition. Because the front teeth would have been well suited for grasping, Masiakasaurus may have consumed small vertebrates, invertebrates, and possibly even fruits.[6]

In 2013, Lee and O'Connor observed that Masiakasaurus would be a good subject for an analysis of theropod growth, considering that there is an abundance of fossil material to examine from a broad range of ontogenetic stages. The study showed that Masiakasaurus grew determinately, and reached full maturity at a small body size. Competing theories that Masiakasaurus specimens represent the juvenile form of a larger-bodied theropod were not supported by the data. Masiakasaurus took 8 to 10 years to grow the size of a large dog. This indicates a rate of growth that is 40% slower than that of comparably sized non-avian theropods, a finding that is supported by the unusual prominence of parallel-fibered bone which is known to be associated with relatively slow growth. However, individuals in this genus grew 40% faster than crocodylians. Lee and O'Connor noted that the evolution of slow growth gave this dinosaur the advantage of minimizing the nutritional investment allocated toward structural growth while living in a semiarid and seasonally stressful environment.[9]

- ^ a b c d Sampson, S.D.; Carrano, M.T.; Forster, C.A. (2001). "A bizarre predatory dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Nature. 409 (6819): 504–506. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..504S. doi:10.1038/35054046. PMID 11206544. S2CID 205013285.

- ^ Grillo, O. N.; Delcourt, R. (2016). "Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king". Cretaceous Research. 69: 71–89. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.001.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 82. ISBN 9780691137209.

- ^ Switek, Brian. "Masiakasaurus Gets a Few Touch-Ups". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Carrano, M.T.; Loewen, M.A.; Sertic, J.J.W. (2011). "New materials of Masiakasaurus knopfleri Sampson, Carrano, and Forster, 2001, and implications for the morphology of the Noasauridae (Theropoda: Ceratosauria)". Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology. 95 (95): 53pp. doi:10.5479/si.00810266.95.1.[1]

- ^ a b c d Carrano, M.T.; Sampson, S.D.; Forster, C.A. (2002). "The osteology of Masiakasaurus knopfleri, a small abelisauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 510–534. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0510:TOOMKA]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524247. S2CID 85655323.

- ^ Rauhut, O.W.M., and Carrano, M.T. (2016). The theropod dinosaur Elaphrosaurus bambergi Janensch, 1920, from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, (advance online publication) doi:10.1111/zoj.12425

- ^ Rogers, R.R.; Krause, D.W.; Rogers, K.C. (2003). "Cannibalism in the Madagascan dinosaur Majungatholus atopus". Nature. 422 (6931): 515–518. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..515R. doi:10.1038/nature01532. PMID 12673249. S2CID 4389583.

- ^ Andrew H. Lee & Patrick M. O’Connor (2013) Bone histology confirms determinate growth and small body size in the noasaurid theropod Masiakasaurus knopfleri. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33(4): 865-876.[2]

- The Geological Society of London (25 January 2001). "Palaeontologists in dire straits name dinosaur for the Sultan of Swing". Retrieved 7 October 2005.