Mongolian cuisine (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Culinary traditions of Mongolia

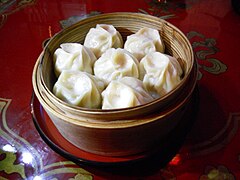

Khuushuur meat pies, buuz dumplings and boiled mutton

From smallest to largest: boortsog cookies, aaruul (dried curds), and ul boov cakes

Mongolian cuisine predominantly consists of dairy products, meat, and animal fats. The most common rural dish is cooked mutton. In the city, steamed dumplings filled with meat—"buuz"— are popular.

The extreme continental climate of Mongolia and the lowest population density in the world of just 2.2 inhabitants/km2 has influenced the traditional diet. Use of vegetables and spices are limited. Due to geographic proximity and deep historic ties with China and Russia, Mongolian cuisine is also influenced by Chinese and Russian cuisine.[1]

Mongolia is one of few Asian countries where rice is not a main staple food. Instead, Mongolian people prefer to eat lamb as their staple food rather than rice.

Wheat, barley, and buckwheat predominate more than rice in modern Mongolia.

Details of the historic cuisine of the Mongolian court were recorded by Hu Sihui in the Yinshan Zhengyao, known to us from the 1456 Ming Dynasty edition manuscript, also surviving in fragments from the Yuan dynasty.[2] Presented to Tugh Temür in 1330, at the height of Mongol power and cultural influence, the Yinshan Zhengyao is a product of the cultural exchange (notably with the Islamic heartland in Mongol Iran) that enriched the Mongol Empire.[3] Food scholars consider the Yinshan Zhengyao evidence for the cultural influence of the Middle East on Mongol food culture, comparable to the Columbian exchange.[4]

Wang Yuanling gives an eyewitness report of a feast at Kubilai Khan's court where kumiss is served with scallions and onions, horse meat, roast mutton, venison, quail, pheasant, diced chicken (tianji) and bear meat, with red wine and congee.[5] According to Marco Polo the Mongols hunted daily in December, January and February when the court was resident at the capital, with a portion of the lions, stags, bears and wild boars sent to the court of the Khan. The Khan was said to keep trained leopards, eagles, and wolves for hunting, and very fine lions that could hunt wild boars, cattle, stags and bears.

Little is known of the early Mongol cuisine, other than the assumption that it would be similar to the general pastoral nomadic foodways of the Steppe. Mongols supplemented the staples of the pastoral nomadic diet (mostly milk and herd) with hunting and gathering, especially as stores of dry curd and cheese grew scarce in the late winter months. Sheep were the most important product of animal husbandry, providing milk for dairy products, some fermented goods, and meat. Horses could provide milk for the iconic kumys, and valued for their hearty, nutritious meat and blood. Less common herd animals were reindeers and sarlag, a type of yak.[6]

As far as hunting, Mongols hunted the wild animals of the steppe. The marmot is one such mentioned in the Yinshan Zhengyao. Grain was often limited in supply, mostly traded for or taken as pillage, although some evidence of agricultural activity is known from 12th century Western Mongolia. The importance of vegetables, fungi and fruits and berries is unknown, but speculated to have been significant. According to the Secret History, Genghis Khan's mother Hoelun was forced to resort to feeding her children from the pastures after the Tatars poisoned her husband Yesugei. The context of this story implies that these types of foods were consumed only out of necessity. The roots and wild fruits mentioned are:[7]

| English | Mongol | Latin |

|---|---|---|

| Scarlet lily bulbs | ja'uqasun | Lilium concolor |

| Garden burnet root | südün | Sanguisorba officinalis |

| Wild apple | ölirsün | Probably Malus pallasiana |

| Bird cherries | moyilsun | Prunus padus |

| Chinese chives | qoqosun | Allium tuberosum |

| Wild garlic | qaliyarsun | Allium victorialis |

| Wild onions | manggirsun | Allium senescens |

| Cinquefoil root | cicigina | Potentilla anserina |

The Yinshan Zhengyao features recipes with Central Asian influence, mostly in north China. Some difference continues in the present day and dishes with lamb, fancy breads and fried dumplings are more typical of north Chinese cuisine, while fish, rice, pork and vegetables are more common in the south.

Some recipes in Yinshan Zhengyao are similar to recipes from medieval Arabic cookbooks. Scholars have proposed a possible West to East diffusion of the cookbook. Of the extant cookbooks, the Arab texts are the earliest and the similarity of Yinshan Zhengyao along with the timing of its compilation after the Mongol conquests may support a West to East diffusion or direct influence upon the Yinshan Zhengyao content, but there is no way to rule out the possibility of an independent Chinese origin.[8] Lactic acid fermentation was used to preserve dairy products like the dried yogurt called kashk in Iran and qimaq in the Yinshan Zhengyao.

The nomads of Mongolia sustain their lives directly from the products of domesticated animals such as cattle, horses, camels, yaks, sheep, and goats, as well as game.[1] Meat is either cooked, used as an ingredient for soups and dumplings, such as buuz, khuushuur, bansh, manti, or dried for winter (borts).[1] The Mongolian diet includes a large proportion of animal fat which is necessary for the Mongols to withstand the cold winters and their hard work. Winter temperatures are as low as −40 °C (−40 °F) and outdoor work requires sufficient energy reserves. Milk and cream are used to make a variety of beverages, as well as cheese and similar products.[9]

The nomads in the countryside are self-supporting on principle. Travelers will find gers marked as guanz in regular intervals near the roadside, which operate as simple restaurants. In the ger, which is a portable dwelling structure (yurt is a Turkic word for a similar shelter, but the name is ger in Mongolian), Mongolians usually cook in a cast-iron or aluminum pot on a small stove, using wood or dry animal dung fuel (argal).

The most common rural dish is cooked mutton, usually without any other ingredients, though potatoes and carrots are common accompaniments in more well to do families. To accompany the meat, vegetables and flour products may be used to create side dishes as well. In Ulaanbaatar, one can often see signs saying "buuz". Those are steamed dumplings filled with meat. Other types of dumplings are boiled in water (bansh, manti), or deep fried in mutton fat (khuushuur). Khuushuur is particularly popular during the Naadam festival, where a particular variety is made that is slightly different to common Khuushuur. Other dishes combine the meat with rice or fresh noodles made into various stews (tsuivan, budaatai khuurga) or noodle soups (guriltai shöl). Sülen is a type of hot pot dish. Gambir (Mongolian: гамбир, pronounced [ɢæmʲbʲĭɾ]) is a flatbread that is commonly made from flour and ghee, served on its own or with sugar.

Boiled meat and innards; the most common meal in a herder's household

Two kinds of dumplings: Buuz (top left) and Khuushuur (lower right)

Another Buuz variant

Khorkhog

Boodog

The most surprising cooking method is only used on special occasions. In this case, the meat (often together with vegetables) gets cooked with the help of stones, which have been preheated in a fire. This either happens with chunks of mutton in a sealed milk can (khorkhog), or within the abdominal cavity of a deboned goat or marmot (boodog).

Milk is boiled to separate the cream (öröm, clotted cream).[9] The remaining skimmed milk is processed into cheese (byaslag), dried curds (aaruul), yogurt, kefir, and a light milk liquor (shimiin arkhi). The most prominent national beverage is airag, which is fermented mare's milk.[9] A popular cereal is barley, which is fried and malted. The resulting flour (arvain guril) is eaten as a porridge in milk fat and sugar or drunk mixed in milky tea. The everyday beverage is salted milk tea (süütei tsai), which may turn into a robust soup by adding rice, meat, or bansh. As a result of the Russian influence during socialism, vodka has also gained some popularity[9] with a number of local brands (usually grain spirits). Boortsog or bawïrsaq is a type of fried dough food found in the cuisines of Central Asia, Idel-Ural, Mongolia and the Middle East. It is shaped into either triangles or sometimes spheres. The dough consists of flour, yeast, milk, eggs, margarine, salt, sugar, and fat.

Süütei Tsai, salted milk tea

Three large stones removing excess liquid from a cheese, Khövsgöl Province

A glass of airag in front of the plastic barrel used to make it

Leather pouch used for fermenting airag the traditional way

Various types of Mongolian sour milk sweets

Aaruul in the process of drying on top of a ger

Aaruul in a serving bowl

Boortsog type of fried dough

Horse meat is eaten in Mongolia and can be found in most grocery stores.

Mongolian sweets include boortsog, a type of biscuit or cookie eaten on special occasions.

Vodka is the most popular alcoholic beverage; Chinggis vodka (named for Genghis Khan) is the most popular brand, making up 30% of the distilled spirits market.[10]

Custom of hospitality

[edit]

The Mongol people had rules of hospitality and social support similar to the Germanic Gastfreundschaft (where it was customary to extend hospitality even to enemies) and Arab Bedouin hospitality. An account of this survives in the Secret History of the Mongols:

After that, when Dobun-mergen one day went to hunt on Toqocaq Rise, he encountered Uriangqadai people in the forest. They had killed a three year old deer and were cooking its ribs and intestines. When Dobun-mergen spoke he said: "Please give me (some meat) as the share of meat due another (nökör sirolqa ke'ejü'ü)." Taking [only] half a breast side of the meat with the lungs, and the hide, they gave all (the rest of the) three year old deer's meat to Dobun-mergen.

- ^ a b c Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2007, p. 268

- ^ Buell, 1

- ^ Buell, 15–25

- ^ Buell, 27

- ^ Buell, 86k

- ^ Buell, 29–35

- ^ Buell, 37

- ^ Buell, 78

- ^ a b c d Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2007, p. 269

- ^ "CHINGGIS Vodka". www.behindcity.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2007) World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, Marshall Cavendish, p. 268 -269 ISBN 0-7614-7633-4

- Buell, P.D. (2010) A Soup for the Qan: Second Revised and Expanded Edition ISBN 9789004180208