Mount Gongga (original) (raw)

Mountain in Sichuan, China

| Mount Gongga | |

|---|---|

Mount Gongga Mount Gongga |

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 7,556 m (24,790 ft)Ranked 41st |

| Prominence | 3,642 m (11,949 ft)Ranked 47th |

| Parent peak | K2 |

| Listing | Ultra |

| Coordinates | 29°35′45″N 101°52′45″E / 29.59583°N 101.87917°E / 29.59583; 101.87917 |

| Geography | |

Mount GonggaLocation in Sichuan Mount GonggaLocation in Sichuan |

|

| Location | Kangding and Luding County, Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan, China |

| Parent range | Daxue Shan (大雪山) |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | October 28, 1932, by Terris Moore and Richard Burdsall |

| Easiest route | Northwest Ridge |

Mount Gongga Northwest Ridge

Orthographic projection centred over Gongga Shan

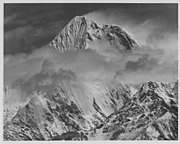

Mount Gongga (simplified Chinese: 贡嘎山; traditional Chinese: 貢嘎山; pinyin: Gònggá Shān), also known as Minya Konka (Khams Tibetan: མི་ཉག་གངས་དཀར་རི་བོ་, Khams Tibetan pinyin: Mi'nyâg Gong'ga Riwo) and colloquially as "The King of Sichuan Mountains", is the highest mountain in Sichuan province, China. It has an elevation of 7,556 m (24,790 ft) above sea level. This makes it the third highest peak in the world outside of the Himalaya/Karakoram range, after Tirich Mir and Kongur Tagh, and the easternmost and most isolated 7,000-metre (23,000 ft) peak in the world. It is situated in the Daxue Shan mountain range, between Dadu River and Yalong River, and is part of the Hengduan mountainous region. From it comes the Hailuogou glacier.

The peak has large vertical relief over the deep nearby gorges.

Mountaineering history

[edit]

The first western explorers in this region heard reports of an extremely high mountain and sought it out. An early remote measurement of the mountain, then called Bokunka, was first performed by the Inner Asian expedition of the Hungarian count Béla Széchenyi between 1877 and 1880.[1] That survey put the altitude of the peak at 7,600 metres (24,900 ft).

Forty-five years later, the mountain, this time called Gang ka, was sketched by China Inland Mission missionary James Huston Edgar from a distance.

In 1929 the explorer Joseph Rock, in an attempt to measure the mountain's altitude, miscalculated its height as 30,250 ft (9,220 m) and cabled the National Geographic Society to announce Minya Konka as the highest mountain in the world.[1] This measurement was immediately viewed with suspicion, and the Society's decision to check Rock's calculations before publication was well-founded. Following discussions with the Society, Rock reduced his claim to 7,803 m (25,600 ft) in his formal publication.

In 1930 Swiss geographer Eduard Imhof led an expedition that measured the altitude of the mountain to be 7,590 m (24,900 ft).[2] A richly illustrated large-format book about the expedition was eventually published by Imhof, Die Großen Kalten Berge von Szetchuan (Orell Fussli Verlag, Zurich, 1974). The book includes many color paintings by Imhof, including images of the Tibetan monastery at the foot of the sacred mountain. The monastery was almost completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, around 1972–74.

A properly equipped American team composed of Terris Moore, Richard Burdsall, Arthur B. Emmons, and Jack T. Young returned to the mountain in 1932 and performed an accurate survey of the peak and its environs. Their summit altitude measurement agreed with Imhof's figure of 7,590 m (24,900 ft). Moore and Burdsall succeeded in climbing to the summit by starting on the west side of the mountain and climbing the Northwest Ridge. This was a remarkable achievement at the time, considering the height of the mountain, its remoteness, and the small size of the group. In addition, this peak was the highest summit reached by Americans until 1958 (though Americans had by that time climbed to higher non-summit points). The book written by the expedition members, Men Against The Clouds,[3] remains a mountaineering classic.

In May 1957 a Chinese mountaineering team claimed to have climbed Minya Konka via the Northwest Ridge route established by Moore and Burdsall. Six people reached the summit with limited climbing experience and primitive equipment, although four climbers died in the effort.[4]

For political reasons, this region of China was made inaccessible to foreign climbers after the 1930s. In 1980 the region was again opened to foreign expeditions. American Lance Owens was the first foreigner to receive permission from the People's Republic of China to lead a mountaineering expedition in China and Tibet, allowing him to climb Gongga Shan (Minya Konka) in 1980. This expedition opened the modern era of American climbing in China. The expedition, organized by Owens and sponsored by the American Alpine Club, attempted the still unclimbed and extremely technical west face of Minya Konka. Members of the expedition included Louis Reichardt, Andrew Harvard, Gary Bocarde, Jed Williamson, and Henry Barber.[5]

The Hailuogou Glacier sliding from the Gongga Mountain 2022-8-19

Graf Béla Széchenyi (Österreichs Illustrierter Zeitung, 1900)- [

![Title page of an expedition report from a member of Graf Béla Széchenyi's expedition[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0e/UB_Maastricht_-_Kreitner_1881_-_title_page.jpg/122px-UB_Maastricht_-_Kreitner_1881_-_title_page.jpg) ](/wiki/File:UB%5FMaastricht%5F-%5FKreitner%5F1881%5F-%5Ftitle%5Fpage.jpg "Title page of an expedition report from a member of Graf Béla Széchenyi's expedition[6]")

](/wiki/File:UB%5FMaastricht%5F-%5FKreitner%5F1881%5F-%5Ftitle%5Fpage.jpg "Title page of an expedition report from a member of Graf Béla Széchenyi's expedition[6]")

Title page of an expedition report from a member of Graf Béla Széchenyi's expedition[6]

Joseph Rock

Eduard Imhof, Die Großen Kalten Berge von Szetschuan.

Minya Konka, photographed from the west. Photograph taken during the 1980 American expedition.

Deaths on the mountain

[edit]

A large number of mountaineering deaths have occurred on Gongga Shan, which has earned a reputation as a difficult and dangerous mountain. While the first ascent route up the Northwest Ridge appears technically straightforward, it is plagued by avalanches due to the mountain's highly unpredictable weather. During the 1957 Chinese ascent of the peak, four of nine climbers died. In 1980 an American climber died in an avalanche on the Northwest Ridge route.[7] In an unsuccessful 1981 attempt on the peak, eight Japanese climbers died in a fall.[8][9] As of 1999, more climbers had died trying to climb the mountain than had reached the summit.[10]

As of 2003, the mountain had been successfully climbed only eight times.[9] In total, 22 climbers had reached the summit and 16 climbers had died in the effort. (These statistics may not take into account the four Chinese climbers killed in the 1957 expedition.)

The Himalayan Index lists five ascents of Gongga Shan between 1982 and 2002, and about seven unsuccessful attempts.[11] There have been several attempts in years since then, which are unlisted in this index.

In October 2017, Chinese media reported that Pavel Kořínek, a Czech national, had reached the top of Gongga Shan, marking the first time since 2002 that the mountain had been successfully climbed.[4] The article summarized the climbing history of Gongga Shan (Minya Konka) as follows:

"Under the long-term action of the glacier, the main peak developed into a cone-shaped, high-angle peak, with surrounding cliffs at 60° to 70°. Coupled with the bad weather in the region, it is difficult to conquer. The summit is much more difficult than Everest. According to incomplete statistics, as of September 2017, a total of 32 people had successfully reached the summit and 21 people were killed during attempts to climb the peak. According to the Sichuan Mountaineering Association, the death rate of Gongga Shan is much higher than Everest and all the 13 peaks over 8000 meters, making it the peak with the highest mountain death rate in the world...."[4]

- ^ a b Arnold Heim: The Glaciation and Solifluction of Minya Gongkar. The Geographical Journal. Vol. 87, No. 5 (May, 1936), pp. 444–450. Published by: The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers)

- ^ "Expedition zum Minya Konka in Chinesisch Tibet 1930". Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ^ R. Burdsall, T. Moore, A. Emmons, and J. Young, Men Against The Clouds (revised edition), The Mountaineers, 1980.

- ^ a b c Jiang, Lin (蒋麟); Zhang, Zhaoting (张肇婷) (2017-10-27). 时隔15年人类再登蜀山之巅. 甘孜日报 [_Garzê Post_] (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- ^ "Asia, China, Gongg Shan (Minya Konka) from the South". American Alpine Club.

- ^ Kreitner, Gustav: Im fernen Osten. Reisen des Grafen Graf Béla Széchenyi in Indien, Japan, China, Tibet und Birma in den Jahren 1877–1880. Viena 1881. In German.

- ^ Rick Ridgeway, Below Another Sky: A Mountain Adventure in Search of a Lost Father, 2000

- ^ Searchers find body missing for 26 years, AAP, Jun 12 2007 Archived June 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b SummitPost Minya Konka (Gongga Shan)

- ^ Macfarlane, Robert (15 October 2012). "Ice, from The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot". Design Observer. Observer Omnimedia LLC. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Himalayan Index". The Alpine Club.

- Jill Neate, High Asia: An Illustrated History of the 7000 Metre Peaks, ISBN 0-89886-238-8

- Michael Brandtner: Minya Konka Schneeberge im Osten Tibets. Die Entdeckung eines Alpin-Paradieses. Detjen-Verlag, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-937597-20-4

- Arnold Heim: Minya Gongkar. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern–Berlin 1933

- Eduard Imhof: Die großen kalten Berge von Szetschuan. Orell Füssli Verlag, Zürich 1974

- Richard Burdsall & Arthur Emmons: Men Against the Clouds: The Conquest of Minya Konka. The Bodley Head, London 1935

- Corrected versions of SRTM digital elevation data

- Trekking Tour to Mt.Minya Konka

- Gongga Shan Travel and Trekking Guide on Chinabackpacker