National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum (original) (raw)

Professional sports hall of fame in New York, U.S.

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

|

|

|---|---|

The Hall of Fame in 2020 The Hall of Fame in 2020 |

|

|

|

| Established | 1936; 89 years ago (1936) (Baseball)Dedicated June 12, 1939 |

| Location | Cooperstown, New York, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 42°42′0″N 74°55′24″W / 42.70000°N 74.92333°W / 42.70000; -74.92333 |

| Type | Professional sports hall of fame |

| Key holdings | August Herrmann Papers Gene Mack Cartoons Roger Kahn Papers Federal League Litigation [1] |

| Collections | Photo Archive National Baseball Hall of Fame Library (Manuscripts, Books, Publications) Recorded Media Collection Artifact Collection [1] |

| Collection size | 250,000 photographs 14,000 hours of moving images and sound recordings 40,000 three-dimensional artifacts [1] |

| Visitors | 260,000/year(average as of 2018)[2] |

| Founder | Stephen Carlton Clark |

| President | Josh Rawitch[3] (since 2021) |

| Chairperson | Jane Forbes Clark[3](Board of Directors) |

| Curator | Tom Shieber[3](Senior Curator) |

| Website | baseballhall.org |

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is a history museum and hall of fame in Cooperstown, New York, operated by private interests. It serves as the central point of the history of baseball in the United States and displays baseball-related artifacts and exhibits, honoring those who have excelled in playing, managing, and serving the sport. The Hall's motto is "Preserving History, Honoring Excellence, Connecting Generations". Cooperstown is often used as shorthand (or a metonym) for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

The Hall of Fame was established in 1939 by Stephen Carlton Clark, an heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune. Clark sought to bring tourists to the village hurt by the Great Depression, which reduced the local tourist trade, and Prohibition, which devastated the local hops industry. Clark constructed the Hall of Fame's building, which was dedicated on June 12, 1939. (His granddaughter, Jane Forbes Clark, is the current chairman of the board of directors.) The erroneous claim that Civil War hero Abner Doubleday invented baseball in Cooperstown was instrumental in the early marketing of the Hall.

An expanded library and research facility opened in 1994.[4] Dale Petroskey became the organization's president in 1999.[5] In 2002, the Hall launched Baseball as America, a traveling exhibit that toured ten American museums over six years. The Hall of Fame has since also sponsored educational programming on the Internet to bring the Hall of Fame to schoolchildren who might not visit. The Hall and Museum completed a series of renovations in spring 2005. The Hall of Fame also presents an annual exhibit at FanFest at the Major League Baseball All-Star Game.

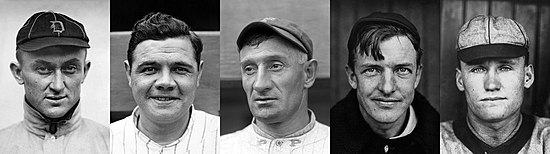

Among baseball fans, "Hall of Fame" means not only the museum and facility in Cooperstown, New York, but the pantheon of players, managers, umpires, executives, and pioneers who have been inducted into the Hall. The first five men elected were Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson and Walter Johnson, chosen in 1936; roughly 20 more were selected before the entire group was inducted at the Hall's 1939 opening. As of January 2024[update], 346 people had been elected to the Hall of Fame, including 274 former professional players, 23 managers, 10 umpires, and 39 pioneers, executives, and organizers. 118 members of the Hall of Fame have been inducted posthumously, including four who died after their selection was announced. Of the 39 members primarily recognized for their contributions to Negro league baseball, 31 were inducted posthumously, including all 26 selected since the 1990s. The Hall of Fame includes one female member, Effa Manley.[6]

The newest members of the Hall of Fame, elected December 8, 2024, are Dick Allen and Dave Parker.

In 2019, former Yankees closer Mariano Rivera became the first player to be elected unanimously.[7] Derek Jeter, Marvin Miller, Ted Simmons, and Larry Walker were to be inducted in 2020, but their induction ceremony was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic[8] until September 8, 2021. The ceremony was open to the public, as COVID restrictions had been lifted.[9]

Players are currently inducted into the Hall of Fame through election by either the Baseball Writers' Association of America (or BBWAA), or the Veterans Committee,[10] which now consists of four subcommittees, each of which considers and votes for candidates from a separate era of baseball. Five years after retirement, any player with 10 years of major league experience who passes a screening committee (which removes from consideration players of clearly lesser qualification) is eligible to be elected by BBWAA members with 10 years' membership or more who also have been actively covering MLB at any time in the 10 years preceding the election (the latter requirement was added for the 2016 election).[11] From a final ballot typically including 25–40 candidates, each writer may vote for up to 10 players; until the late 1950s, voters were advised to cast votes for the maximum 10 candidates. Any player named on 75% or more of all ballots cast is elected. A player who is named on fewer than 5% of ballots is dropped from future elections. In some instances, the screening committee had restored their names to later ballots, but in the mid-1990s, dropped players were made permanently ineligible for Hall of Fame consideration, even by the Veterans Committee. A 2001 change in the election procedures restored the eligibility of these dropped players; while their names will not appear on future BBWAA ballots, they may be considered by the Veterans Committee.[12] Players receiving 5% or more of the votes but fewer than 75% are reconsidered annually until a maximum of ten years of eligibility (lowered from fifteen years for the 2015 election).[13]

Seven of the American League's 1937 All-Star players: Lou Gehrig, Joe Cronin, Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, Charlie Gehringer, Jimmie Foxx, and Hank Greenberg. All seven were inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Under special circumstances, certain players may be deemed eligible for induction even though they have not met all requirements. Addie Joss was elected in 1978, despite only playing nine seasons before he died of meningitis. Additionally, if an otherwise eligible player dies before his fifth year of retirement, then that player may be placed on the ballot at the first election at least six months after his death. Roberto Clemente set the precedent: the writers put him up for consideration after his death on New Year's Eve, 1972, and he was inducted in 1973.

The five-year waiting period was established in 1954 after an evolutionary process. In 1936 all players were eligible, including active ones. From the 1937 election until the 1945 election, there was no waiting period, so any retired player was eligible, but writers were discouraged from voting for current major leaguers. Since there was no formal rule preventing a writer from casting a ballot for an active player, the scribes did not always comply with the informal guideline; Joe DiMaggio received a vote in 1945, for example. From the 1946 election until the 1954 election, an official one-year waiting period was in effect. (DiMaggio, for example, retired after the 1951 season and was first eligible in the 1953 election.) The modern rule establishing a wait of five years was passed in 1954, although those who had already been eligible under the old rule were grandfathered into the ballot, thus permitting Joe DiMaggio to be elected within four years of his retirement.

Lineup for Yesterday

Z is for Zenith

The summit of fame.

These men are up there.

These men are the game.

Contrary to popular belief, no formal exception was made for Lou Gehrig (other than to hold a special one-man election for him): there was no waiting period at that time, and Gehrig met all other qualifications, so he would have been eligible for the next regular election after he retired during the 1939 season. However, the BBWAA decided to hold a special election at the 1939 Winter Meetings in Cincinnati, specifically to elect Gehrig (most likely because it was known that he was terminally ill, making it uncertain that he would live long enough to see another election). Nobody else was on that ballot, and the numerical results have never been made public. Since no elections were held in 1940 or 1941, the special election permitted Gehrig to enter the Hall while still alive.

If a player fails to be elected by the BBWAA within 10 years of his eligibility for election, he may be selected by the Veterans Committee. Following changes to the election process for that body made in 2010 and 2016, the Veterans Committee is now responsible for electing all otherwise eligible candidates who are not eligible for the BBWAA ballot — both long-retired players and non-playing personnel (managers, umpires, and executives). From 2011 to 2016, each candidate could be considered once every three years;[15] now, the frequency depends on the era in which an individual made his greatest contributions.[16] A more complete discussion of the new process is available below.

From 2008 to 2010, following changes made by the Hall in July 2007, the main Veterans Committee, then made up of living Hall of Famers, voted only on players whose careers began in 1943 or later. These changes also established three separate committees to select other figures:

- One committee voted on managers and umpires for induction in every even-numbered year. This committee voted only twice—in 2007 for induction in 2008 and in 2009 for induction in 2010.

- One committee voted on executives and builders for induction in every even-numbered year. This committee conducted its only two votes in the same years as the managers/umpires committee.

- The pre–World War II players committee was intended to vote every five years on players whose careers began in 1942 or earlier. It conducted its only vote as part of the election process for induction in 2009.[17]

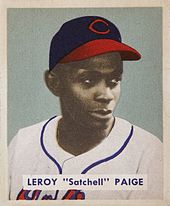

1971 inductee Satchel Paige

Players of the Negro leagues have also been considered at various times, beginning in 1971. In 2005, the Hall completed a study on African American players between the late 19th century and the integration of the major leagues in 1947, and conducted a special election for such players in February 2006; seventeen figures from the Negro leagues were chosen in that election, in addition to the eighteen previously selected. Following the 2010 changes, Negro leagues figures were primarily considered for induction alongside other figures from the 1871–1946 era, called the "Pre-Integration Era" by the Hall; since 2016, Negro leagues figures are primarily considered alongside other figures from what the Hall calls the "Early Baseball" era (1871–1949).

Predictably, the selection process catalyzes endless debate among baseball fans over the merits of various candidates. Even players elected years ago remain the subjects of discussions as to whether they deserved election. For example, Bill James' 1994 book Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame? goes into detail about who he believes does and does not belong in the Hall of Fame.

Non-induction of banned players

[edit]

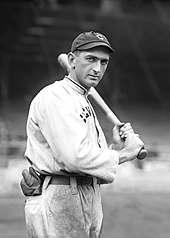

"Shoeless Joe" Jackson in 1913

The selection rules for the Baseball Hall of Fame were modified to prevent the induction of anyone on Baseball's "permanently ineligible" list. The most prominent former players to be affected are Pete Rose and "Shoeless Joe" Jackson—many others have been barred from participation in MLB, but none have Hall of Fame qualifications on the level of Jackson or Rose. Jackson and Rose were both banned from MLB for life for actions related to gambling on games involving their own teams.

Jackson was determined to have cooperated with those who conspired to intentionally lose the 1919 World Series, and for accepting payment for losing, although his actual level of culpability is fiercely debated. The ensuing Black Sox Scandal led directly to baseball's Rule 21, prominently posted in every clubhouse locker room, which mandates permanent banishment from MLB for having a gambling interest of any sort on a game in which a player, manager or umpire is directly involved.

Rose voluntarily accepted a permanent spot on the ineligible list in return for MLB's promise to make no official finding in relation to alleged betting on the Cincinnati Reds when he was their manager in the 1980s. No credible evidence has ever emerged to support allegations that Rose bet against his team and/or that his betting influenced his managerial decisions, nevertheless, the betting constituted a clear violation of the aforementioned Rule 21. After years of denial, Rose admitted that he bet on the Reds in his 2004 autobiography.

Baseball fans are deeply split on the issue of whether Rose and/or Jackson (now both deceased) should remain banned or have their punishments posthumously revoked. Writer Bill James, though he advocates Rose eventually making it into the Hall of Fame, compared the people who want to put Jackson in the Hall of Fame to "those women who show up at murder trials wanting to marry the cute murderer".[18]

Changes to Veterans Committee process

[edit]

The actions and composition of the Veterans Committee have been at times controversial, with occasional selections of contemporaries and teammates of the committee members over seemingly more worthy candidates.[19][20][21][22][23]

In 2001, the Veterans Committee was reformed to comprise the living Hall of Fame members and other honorees.[24] The revamped Committee held three elections, in 2003 and 2007, for both players and non-players, and in 2005 for players only. No individual was elected in that time, sparking criticism among some observers who expressed doubt whether the new Veterans Committee would ever elect a player. The Committee members, most of whom were Hall members, were accused of being reluctant to elect new candidates in the hope of heightening the value of their own selection. After no one was selected for the third consecutive election in 2007, Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt noted, "The same thing happens every year. The current members want to preserve the prestige as much as possible, and are unwilling to open the doors."[12] In 2007, the committee and its selection processes were again reorganized; the main committee then included all living members of the Hall, and voted on a reduced number of candidates from among players whose careers began in 1943 or later. Separate committees, including sportswriters and broadcasters, would select umpires, managers and executives, as well as players from earlier eras.

In the first election to be held under the 2007 revisions, two managers and three executives were elected in December 2007 as part of the 2008 election process. The next Veterans Committee elections for players were held in December 2008 as part of the 2009 election process; the main committee did not select a player, while the panel for pre–World War II players elected Joe Gordon in its first and ultimately only vote. The main committee voted as part of the election process for inductions in odd-numbered years, while the pre-World War II panel would vote every five years, and the panel for umpires, managers, and executives voted as part of the election process for inductions in even-numbered years.

Further changes to the Veterans Committee process were announced by the Hall in July 2010, July 2016, and April 2022.

Per the latest changes, announced on April 22, 2022, the multiple eras previously utilized were collapsed to three, to be voted on in an annual rotation (one per year):[25]

- Contemporary Baseball Era (1980–present) players

- Contemporary Baseball Era (1980–present) non-players (managers, executives, and umpires)

- Classic Baseball Era (prior to 1980)

A one-year waiting period beyond potential BBWAA eligibility (which had been abolished in 2016) was reintroduced, thus restricting the committee to considering players retired for at least 16 seasons.[25]

The eligibility criteria for Era Committee consideration differ between players, managers, and executives.[26]

- Players: When a player is no longer eligible on the BBWAA ballot (either 15 years after retirement—five-year period and the 10 years after he first becomes eligible to appear on the BBWAA ballot or when the player is not eligible after earning less than five percent of the BBWAA ballot during a year), he will be considered by the respective committee.

- The Hall has not yet established a policy on when players who die while active or during the standard five-year waiting period for BBWAA eligibility will be eligible for committee consideration. As noted earlier, such players become eligible for the BBWAA ballot six months after their deaths.

- Managers and umpires who have served at least 10 seasons in that role are eligible five years after retirement, unless they are 65 or older, in which case the waiting period is six months.

- Executives are eligible five years after retirement, or upon reaching age 70. For those who meet the age cutoff, they are explicitly eligible for consideration regardless of their current position in an organization or their status as active or retired. Before the 2016 changes to the committee system, active executives 65 years or older were eligible for consideration.[16]

Players and managers with multiple teams

[edit]

While the text on a player's or manager's plaque lists all teams for which the inductee was a member in that specific role, inductees are usually depicted wearing the cap of a specific team, though in a few cases, like umpires, they wear caps without logos. (Executives are not depicted wearing caps.) Additionally, as of 2015, inductee biographies on the Hall's website for all players and managers, and executives who were associated with specific teams, list a "primary team", which does not necessarily match the cap logo. The Hall selects the logo "based on where that player makes his most indelible mark."[27]

Frank Robinson with the Cincinnati Reds in 1961

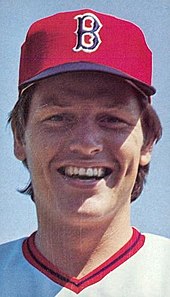

Carlton Fisk with the Boston Red Sox in 1976

Dave Winfield with the San Diego Padres c. 1977

Although the Hall always made the final decision on which logo was shown, until 2001 the Hall deferred to the wishes of players or managers whose careers were linked with multiple teams. Some examples of inductees associated with multiple teams are the following:

- Frank Robinson: Robinson chose to have the Baltimore Orioles cap displayed on his plaque, although he had played ten seasons with the Cincinnati Reds and six seasons with Baltimore. Robinson won four pennants and two World Series with the Orioles and one pennant with Cincinnati. His second World Series ring came in the 1970 World Series against the Reds. Robinson also won an MVP award while playing for each team.

- Catfish Hunter: Hunter chose not to have any logo on his cap when elected to the Hall of Fame in 1987. Hunter had success for both teams for which he played – the Kansas City/Oakland Athletics (his first ten seasons) and the New York Yankees (his final five seasons). Furthermore, both during and after his career he maintained good relations with both teams and their respective owners (Charles Finley and George Steinbrenner), and did not wish to slight either team by selecting the other.

- Nolan Ryan: Born and raised in Texas, Ryan entered the Hall in 1999 wearing a Texas Rangers cap on his plaque, although he spent only five seasons with the Rangers, while raised in the Houston area and having longer and more successful tenures with the Houston Astros (nine seasons, 1980–88 and his record-setting fifth career no-hitter) and California Angels (eight seasons, 1972–79 and the first four of his seven career no-hitters). Ryan's only championship was as a member of the New York Mets in 1969. Ryan finished his career with the Rangers, reaching his 5,000th strikeout and 300th win, and throwing the last two of his no-hitters. He had personally chosen the Rangers due to these figures as well as because Texas encompasses the city of Houston, thereby representing both teams. Despite this, his biography on the Hall's website lists his primary team as the Angels. Ryan later took ownership of the Rangers when they were sold to his Rangers Baseball Express group in 2010. He sold his Rangers interest in 2013. From 2014 to 2019, Nolan was in the Astros' front office as a special assistant. In 2020 Ryan discontinued his executive role with the Astros. The minor-league team in which he has an ownership interest, the Round Rock Express of Round Rock, Texas outside of Austin, will be the AAA franchise of the Texas Rangers.[28][29]

- Reggie Jackson: Jackson chose to be depicted with a Yankees cap over an Athletics cap. As a member of the Kansas City/Oakland A's, Jackson played ten seasons (1967–75, '87), winning three World Series (1972, 1973, 1974) and the 1973 AL MVP Award. During his five years in New York (1977–81), Jackson won two World Series (1977–78), with his crowning achievement occurring during Game Six of the 1977 World Series, when he hit three home runs on consecutive pitches and earned his nickname "Mr. October".

- Carlton Fisk: Fisk went into the hall with a Boston Red Sox cap on his plaque in 2000 despite having played with the Chicago White Sox longer and posting more significant numbers with the White Sox. Fisk's choice of the Red Sox was likely due to his being a New England native, as well as his famous "Stay fair!" walk-off home run in Game Six of the 1975 World Series for which he is most associated.

- Sparky Anderson: Also in 2000, Anderson entered the Hall with a Cincinnati Reds cap on his plaque despite managing almost twice as many seasons with the Detroit Tigers (17 in Detroit; nine in Cincinnati). He chose the Reds to honor that team's former general manager Bob Howsam, who gave him his first major-league managing job. Anderson won two World Series with the Reds and one with the Tigers.

- Dave Winfield: Winfield had spent the most years in his career with the Yankees and had great success there, though he chose to go into the Hall as a member of the San Diego Padres due to his feud with Yankees owner George Steinbrenner.

In all of the above cases, the "primary team" is the team for which the inductee spent the largest portion of his career except for Ryan, whose primary team is listed as the Angels despite playing one fewer season for that team than for the Astros.

In 2001, the Hall of Fame decided to change the policy on cap logo selection, as a result of rumors that some teams were offering compensation, such as number retirement, money, or organizational jobs, in exchange for the cap designation. (For example, though Wade Boggs denied the claims, some media reports had said that his contract with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays required him to request depiction in the Hall of Fame as a Devil Ray.)[30] The Hall decided that it would no longer defer to the inductee, though the player's wishes would be considered, when deciding on the logo to appear on the plaque. Newly elected members affected by the change include the following:

- Gary Carter: Inducted in 2003, Carter was the first player to be affected by the new policy. Carter won his only championship with the 1986 New York Mets, and wanted his induction plaque to depict him wearing a Mets cap, though he had spent twelve years (1974–84, 1992) with the Montreal Expos and five (1985–89) with the Mets. The Hall of Fame decided that Carter's impact on the Montreal franchise warranted depicting him with an Expos cap.[31][32]

- Wade Boggs: Boggs's only title was as a member of the 1996 New York Yankees, for whom he played from 1993 to 1997, but his best career numbers were posted during his 11 years (1982–92) with the Boston Red Sox. Boggs would eventually be depicted wearing a Boston cap for his 2005 induction.

- Andre Dawson: Dawson's cap depicts him as a member of the Expos, his team for eleven years, despite his expressed preference to be shown as a member of the Chicago Cubs. While Dawson played only six years with the Cubs, five of his eight All-Star appearances were as a Cub, and his only MVP award came in his first year with the team in 1987.[33][34]

- Tony La Russa: Manager La Russa chose not to have a logo after managing three teams over 33 years—the Chicago White Sox, Oakland Athletics, and St. Louis Cardinals. His greatest successes were with the A's (three pennants and a World Series title in 10 years) and Cardinals (three pennants and two World Series in 16 years). Nonetheless, La Russa felt that his induction to the Hall was due to his tenures with all three teams, and stated that not including a logo meant that "fans of all [three] clubs can celebrate this honor with me."[35] La Russa's biography on the Hall's website lists his primary team as the Cardinals.

- Greg Maddux: Although Maddux had his greatest success while with the Atlanta Braves for 11 seasons, he had two stints with the Chicago Cubs for a total of 10 seasons, including the first seven of his MLB career. Maddux believed that both fanbases were equally important in his career, and so the cap on his plaque does not feature any logo.[35] His biography on the Hall's website lists his primary team as the Braves.

- Randy Johnson: Johnson played for six teams in a 22-year career, but spent the bulk of it with the Seattle Mariners (10 seasons) and Arizona Diamondbacks (8 seasons). While enjoying great success with both teams, he had more significant honors with the Diamondbacks. Four of Johnson's five Cy Young Awards (consecutively from 1999 to 2002), his only title (in 2001), his pitching triple crown (2002), and his perfect game (2004) all came with Arizona. Accordingly, he and the Hall agreed his plaque should feature a Diamondbacks logo.[36] His biography on the Hall's website lists his primary team as the Mariners.

- Vladimir Guerrero: Guerrero played the majority of his career with the Montreal Expos, spending eight of his sixteen seasons with the team. However, he recorded the majority of his success during his time with the Angels, including five out of his nine All-Star selections, his MVP award, four out of his eight Silver Slugger awards, and all five of his playoff berths. Guerrero ultimately had an Angels logo on his plaque, becoming the only member of the team to have as such. His biography on the Hall's website lists his primary team as the Expos.

- Mike Mussina, who played 10 seasons with the Baltimore Orioles and eight seasons with the New York Yankees, decided to go into the Hall without a logo on his plaque, saying "I don't feel like I can pick one team over the other because they were both great to me. I did a lot in Baltimore and they gave me the chance and then in New York we went to the playoffs seven of eight years, and both teams were involved. To go in with no logo was the only decision I felt good about".[37] Mussina's biography at the Hall lists his primary team as the Orioles.[38]

- Roy Halladay was posthumously elected to the Hall on January 22, 2019,[39] in his first year of eligibility, garnering 85.4 percent of the vote. Halladay was a six-time All-Star and won a Cy Young award with the Toronto Blue Jays from 1998 to 2009, and then was a two-time All-Star and won a Cy Young award with the Philadelphia Phillies over his final four seasons. He spent 12 of his 16 MLB seasons with the Blue Jays and earned 148 of his 203 victories with them, although his team never reached the playoffs. For the Phillies, he threw a perfect game and a postseason no-hitter, though his final two seasons were injury-plagued.[40] Halladay was quoted as saying after he retired in 2013 that he'd like to enter the Hall of Fame as a Blue Jay,[41] and he signed a ceremonial contract to retire with Toronto. However, he died in a plane crash on November 7, 2017. The Hall deferred to the wishes of his wife and sons who chose not to have a logo for his cap, which leaves Roberto Alomar as the sole Cooperstown inductee as a Blue Jay.[42][43][44] Halladay's biography on the Hall's website lists his primary team as the Blue Jays.[45]

Sam Crane (who had played a decade in 19th century baseball before becoming a manager and sportswriter) had first approached the idea of making a memorial to the great players of the past in what was believed to have been the birthplace of baseball: Cooperstown, New York, but the idea did not muster much momentum until after his death in 1925. In 1934, the idea for establishing a Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum was devised by several individuals, such as Ford C. Frick (president of the National League) and Alexander Cleland, a Scottish immigrant who decided to serve as the first executive secretary for the Museum for the next seven years that worked with the interests of the Village and Major League Baseball. Stephen Carlton Clark (a Cooperstown native) paid for the construction of the museum, which was planned to open in 1939 to mark the "Centennial of Baseball", which included renovations to Doubleday Field. William Beattie served as the first curator of the museum.[46][47][48]

According to the Hall of Fame, approximately 260,000 visitors enter the museum each year,[49] and the running total has surpassed 17 million.[2] These visitors see only a fraction of its 40,000 artifacts, 3 million library items (such as newspaper clippings and photos) and 140,000 baseball cards.[50]

The Hall has seen a noticeable decrease in attendance since the mid-2010s. A 2013 story on ESPN.com about the village of Cooperstown and its relation to the game partially linked the reduced attendance with Cooperstown Dreams Park, a youth baseball complex about 5 miles (8.0 km) away in the town of Hartwick. The 22 fields at Dreams Park currently draw 17,000 players each summer for a week of intensive play; while the complex includes housing for the players, their parents and grandparents must stay elsewhere. According to the story,[51]

Prior to Dreams Park, a room might be filled for a week by several sets of tourists. Now, that room will be taken by just one family for the week, and that family may only go into Cooperstown and the Hall of Fame once. While there are other contributing factors (the recession and high gas prices among them), the Hall's attendance has tumbled since Dreams Park opened. The Hall drew 383,000 visitors in 1999. It drew 262,000 last year.

Plaque Gallery in 2001. The central pillar is for the newest (2000) inductees at the time.

Gallery during 2007 HOF induction weekend

- Baseball at the Movies houses baseball movie memorabilia while a screen shows footage from those movies.

- The Bullpen Theater is the site of daily programming at the museum (trivia games, book discussions, etc.) and is decorated with pictures of famous relief pitchers.

- Inductee Row features images of Hall of Famers inducted from 1937 to 1939.

- The Perez-Steele Art Gallery features art of all media related to baseball. Dick Perez served as an artist for various projects at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for 20 years, starting in 1981 [52][53]

- The Plaque Gallery, the most recognizable site at the museum, contains induction plaques of all members. Since 2016, sculptor Tom Tsuchiya has been creating the bas-relief likeness plaques due to a commission from Matthews International.[54]

- The Sandlot Kids Clubhouse has various interactive displays for young children.

- A theater area continually plays the popular Abbott and Costello routine "Who's on First?"

- Scribes and Mikemen honors BBWAA Career Excellence Award and Ford C. Frick Award winners with a photo display and has artifacts related to baseball writing and broadcasting. Floor-to-ceiling windows at the Scribes and Mikemen exhibit face an outdoor courtyard with statues of Johnny Podres and Roy Campanella (representing the Brooklyn Dodgers 1955 championship team), and an unnamed All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player. A Satchel Paige statue was unveiled and dedicated during the 2006 Induction Weekend.[50]

- An Education Gallery hosts school groups and, in the summer, presentations about artifacts from the museum's collection.

- The Grandstand Theater features a 12-minute multimedia film. The 200-seat theater, complete with replica stadium seats, is decorated to resemble old Comiskey Park.[55]

- The Game is the major feature of the second floor. It is where the most artifacts are displayed. The Game is set up in a timeline format, starting with baseball's beginnings and culminating with the game we know today. There are several offshoots of this meandering timeline:

- Taking The Field (19th century baseball)

- Babe Ruth: His Life and Legend

- The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball (the Museum's newest permanent exhibit documenting pre-Negro leagues history through the present day)

- Diamond Dreams (women in baseball)

- ¡Viva Baseball! (a bilingual exhibit, in English and Spanish, that celebrates baseball in Latin America)

Whole New Ballgame —

the modern game

- Whole New Ballgame opened in 2015 and is located in the Janetschek Gallery. This exhibit completes the timeline of baseball through the last 45 years into the game we know today. It features environmental video walls and new interactive elements to go along with artifacts from the Museum's collection.

- The Today's Game exhibit holds objects donated to the Hall of Fame from the past year or two.

Baseball Timeline, on the 2nd floor

- Autumn Glory is devoted to post-season baseball and has, among other artifacts, a case of World Series rings from the 1900s to present.

- Hank Aaron: Chasing the Dream

- One for the Books tells the story of baseball's most cherished records through more than 200 artifacts. The exhibit allows fans to search records dating back through baseball history via an interactive Top Ten Tower while giving visitors a look at exciting moments throughout the years via a multimedia wall.

- BBWAA awards: Replicas of various awards distributed by the BBWAA at the end of each season, along with a list of past winners.

- A case dedicated to Ichiro Suzuki setting the major league record for base hits in a single season, with 262 in 2004, after George Sisler had held the record for 84 years with 257.

- An inductee database touch-screen computer with statistics for every inductee.

- Programs from every World Series.

- Sacred Ground is devoted entirely to ballparks and everything about them, especially the fan experience and the business of a ballpark. The centerpiece is a computer tour of three former ballparks: Boston's South End Grounds, Chicago's Comiskey Park, and Brooklyn's Ebbets Field.

- The Your Team Today exhibit is built like a baseball clubhouse, with 30 glass-enclosed locker stalls, one for each Major League franchise. In each stall there is a jersey and other items from the designated big league team, along with a brief team history.

1982 unauthorized sales

[edit]

A controversy erupted in 1982, when it emerged that some historic items given to the Hall had been sold on the collectibles market. The items had been lent to the Baseball Commissioner's office, gotten mixed up with other property owned by the Commissioner's office and employees of the office, and moved to the garage of Joe Reichler, an assistant to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who sold the items to resolve his personal financial difficulties. Under pressure from the New York Attorney General, the Commissioner's Office made reparations, but the negative publicity damaged the Hall of Fame's reputation, and made it more difficult for it to solicit donations.[56]

2014 commemorative coins

[edit]

Examples of the National Baseball Hall of Fame coins produced by the United States Mint

In 2012, Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed a law ordering the United States Mint to produce and sell commemorative, non-circulating coins to benefit the private, non-profit Hall.[57][58] The bill, H.R. 2527, was introduced in the United States House of Representatives by Rep. Richard Hanna, a Republican from New York, and passed the House on October 26, 2011.[59] The coins, which depict baseball gloves and balls, are the first concave designs produced by the Mint. The mintage included 50,000 gold coins, 400,000 silver coins, and 750,000 clad (nickel-copper) coins. The Mint released them on March 27, 2014, and the gold and silver editions quickly sold out. The Hall receives money from surcharges included in the sale price: a total of $9.5 million if all the coins are sold.[60]

- All-American Girls Professional Baseball League § National Women's Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Award share

- Baseball awards § United States

- Bob Feller Act of Valor Award

- Honor Rolls of Baseball (1946) (managers, executives, writers, umpires)

- List of Major League Baseball awards

- List of members of the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

- Nisei Baseball Research Project

- ^ a b c "Archive and Collection". Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ a b "Hall of Fame Welcomes 17 Millionth Visitor". Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c "President and Senior Staff". Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Museum History". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ^ The Official Site of Major League Baseball: News: HOF president Petroskey resigns Archived March 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine from the Major League Baseball website

- ^ "News". Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Mariano Rivera, other Baseball Hall of Fame inductees enter amid fanfare". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. July 21, 2019. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ Hoch, Bryan (April 29, 2020). "2020 HOF induction postponed to July 2021". mlb.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Martin, Dan (June 22, 2021). "Derek Jeter's Hall of Fame induction won't have any restrictions". New York Post. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Following changes to the voting procedure in 2010, the official name is "Committee to Consider Managers, Umpires, Executives and Long-Retired Players". The term "Veterans Committee" comes from the former official name of "Committee on Baseball Veterans". Although the Hall no longer uses "Veterans Committee", that term is still widely used by baseball media.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Announces Change to BBWAA Voting Electorate" (Press release). National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. July 28, 2015. Archived from the original on August 5, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ a b Walker, Ben (February 28, 2007). "Vets committee throws another shutout at Hall of Fame". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ Bloom, Barry M. (July 26, 2014). "Hall reduces eligibility from 15 years to 10". Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ "Baseball Almanac". Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Board of Directors Restructures Procedures for Consideration of Managers, Umpires, Executives and Long-Retired Players" (Press release). National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. July 26, 2010. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ^ a b "Hall of Fame Makes Series of Announcements" (Press release). National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. July 23, 2016. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ National Baseball Hall of Fame (2009). "Rules for election of pre–World War II players". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on November 23, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2009.

- ^ James (1995:358)

- ^ Chass, Murray (August 7, 2001). "More Vets Eligible For Hall In Baseball". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ Enders, Eric (August 8, 2001). "Same Old Story". Baseball Think Factory. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ Traven, Neal (January 14, 2003). "A Brief History of the Veterans Committee". Baseball Prospectus. Archived from the original on November 1, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ Leo, John (January 24, 1988). "Housecleaning Plan for the Hall of Fame". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ Jaffe, Jay (June 2, 2008). "Marvin Miller". Prospectus Q&A. Baseball Prospectus. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ "Changes to Veterans Committee Procedures". baseballhalloffame.org. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

- ^ a b "Hall of Fame Restructures Era Committee, Frick Award Voting". baseballhall.org. April 22, 2022.

- ^ "Era Rules for Election". Eras Committees. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ "Who decides what team logo will be used on Hall of Fame plaques?". Hall of Famers: FAQ. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. 2009. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ Sheinin, Dave (November 8, 2019). "Astros' upheaval continues with change atop business operations structure". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Reichard, Kevin (December 9, 2020). "Rangers Return to Round Rock for 2021". Ballpark Digest. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Muder, Craig (January 6, 2005). "Boggs, Sandberg field queries as new Hall of Famers". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Czerwinski, Kevin T. (January 16, 2012). "Kid catches Cooperstown spotlight: Carter 'happy' to go into Hall as an Expo". MLB.com. Retrieved January 16, 2003.[_dead link_]

- ^ Friedman, Andy (February 24, 2016). "Hall of Fame Caps That Could Have Been". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Mitchell, Fred (January 27, 2010). "Dawson 'disappointed' he won't wear Cubs cap". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ "Hall denies Dawson's Cubs request, must enter as an Expo". Associated Press. January 27, 2010. Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Kruth, Cash (January 23, 2014). "Maddux, La Russa won't have logos on Hall caps". Major League Baseball. Retrieved September 27, 2017.[_permanent dead link_]

- ^ "Cap Selection Announced for Randy Johnson" (Press release). National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. January 16, 2015. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ "Baseball Hall of Fame: Mike Mussina was equally brilliant for both Yankees and Orioles". Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "Mike Mussina". Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ Schoenfield, David (January 22, 2019). "Mariano Rivera, Edgar Martinez, Roy Halladay and Mike Mussina joining Hall of Fame". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "Which team will Halladay represent in the Hall of Fame? The decision was easy for his family". NBC Sports Philadelphia. January 23, 2019. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Rick Zamperin: Roy Halladay won't enter Hall of Fame as a Blue Jay | Globalnews.ca". globalnews.ca. January 23, 2019. Archived from the original on January 25, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Blue Jays: Only choice is to respect the Halladay family's decision". January 24, 2019. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Ford, Bob (January 23, 2019). "Roy Halladay would have wanted his Hall of Fame plaque to have a Phillies hat | Bob Ford". Inquirer.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Halladay won't have team logo on HOF plaque". ESPN.com. January 24, 2019. Archived from the original on February 4, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Roy Halladay". Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Tom Verducci's Hall of Fame Ballot: Rolen and Wagner Make the Cut". Sports Illustrated. January 26, 2021. Archived from the original on December 25, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ "1939 Cooperstown Centennial | 1939 baseball centennial". Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ "Cleland, Alexander – People & Institutions – eMuseum". Archived from the original on December 25, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Welcomes 17 Millionth Visitor". Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2019. Comments: Amounts based on last million visitors (46 months) — 300,000 was accurate for the previous million (40 months).

- ^ a b "Staff Directory". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on April 11, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ Caple, Jim (July 26, 2013). "Dreams, reality alive in Cooperstown". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ Kashatus, William C. (July 23, 2010). "A portrait of the portraitist". Philly.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Kashatus, William C. (2010) "Introduction". In Perez, Dick (2010). The Immortals: An Art Collection of Baseball's Best. Dick Perez (self-published). ISBN 9780692008508.

- ^ O'Brien, Keith (July 22, 2022). "The National Baseball Hall of Fame will induct several new members". www.npr.org/. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023.

- ^ National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum: Hall of Fame News Archived August 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James, Bill (1994). The Politics of Glory. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. pp. 295–298. ISBN 0-02-510774-7.

- ^ Pub. L. 112–152: National Baseball Hall of Fame Commemorative Coin Act (text) (PDF)

- ^ "National Baseball Hall of Fame Commemorative Coin Act Signed into Law by President Obama". press release. National Baseball Hall of Fame. August 3, 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ "H.R. 2527: National Baseball Hall of Fame Commemorative Coin Act". GovTrack.us. November 1, 2011. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ "Senator Gillibrand Introduces National Baseball Hall of Fame Commemorative Coin Act". press release. National Baseball Hall of Fame. January 26, 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- Official website

- Hall of Fame History from Major League Baseball

- Awards and Honors. Baseball-Reference.com (including HOF inductees, Hall of Famer Batting and Pitching Stats, and HOF Voting Results for 1936 to present)