Philipp Franz von Siebold (original) (raw)

German biologist and traveler

| Philipp Franz von Siebold | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | (1796-02-17)17 February 1796Würzburg, Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg |

| Died | 18 October 1866(1866-10-18) (aged 70)Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation(s) | Physician, botanist |

| Partner(s) | Kusumoto Taki, Helene von Gagern |

| Children | Kusumoto Ine, Alexander von Siebold, Heinrich von Siebold |

Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (17 February 1796 – 18 October 1866) was a German physician, botanist and traveller. He achieved prominence by his studies of Japanese flora and fauna and the introduction of Western medicine in Japan. He was the father of the first female Japanese doctor educated in Western medicine, Kusumoto Ine.

Portrait of Siebold by Kawahara Keiga, 1820s

Illustration made for Siebold by Kawahara Keiga of the crab Carcinoplax longimana, 1820s

Pale-edged stingray by Kawahara for Siebold, 1820s

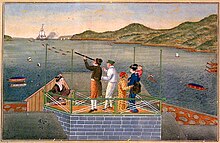

Kawahara Keiga: Arrival of a Dutch Ship. Siebold at Dejima with his Japanese lover Kusumoto Otaki and their baby-daughter Kusumoto Ine observing with a teresukoppu (telescope) a Dutch ship towed into Nagasaki harbour

Kusumoto Taki (1807–1865)

Siebold's daughter Kusumoto Ine (1827–1903), first female Japanese western physician and court physician to the Japanese empress

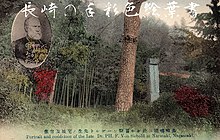

Portrait and residence of Siebold at Narutaki, Nagasaki

Siebold Nagasaki Park, Nagasaki

Title page of _Flora Japonica, part 2, Leiden 1870

Signed portrait from 1875

Born into a family of doctors and professors of medicine in Würzburg (then in the Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg, later part of Bavaria), Siebold initially studied medicine at the University of Würzburg from November 1815,[1] where he became a member of the Corps Moenania Würzburg. One of his professors was Franz Xaver Heller (1775–1840), author of the _Flora Wirceburgensis ("Flora of the Grand Duchy of Würzburg", 1810–1811).[1] Ignaz Döllinger (1770–1841), his professor of anatomy and physiology, however, most influenced him. Döllinger was one of the first professors to understand and treat medicine as a natural science. Siebold stayed with Döllinger, where he came in regular contact with other scientists.[1] He read the books of Humboldt, a famous naturalist and explorer, which probably raised his desire to travel to distant lands.[1] Philipp Franz von Siebold became a physician by earning his M.D. degree in 1820. He initially practiced medicine in Heidingsfeld, in the Kingdom of Bavaria, now part of Würzburg.[1]

Invited to Holland by an acquaintance of his family, Siebold applied for a position as a military physician, which would enable him to travel to the Dutch colonies.[1] He entered the Dutch military service on 19 June 1822, and was appointed as ship's surgeon on the frigate Adriana, sailing from Rotterdam to Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies (now called Indonesia).[1] On his trip to Batavia on the frigate Adriana, Siebold practiced his knowledge of the Dutch language and also rapidly learned Malay. During the long voyage he also began a collection of marine fauna.[1] He arrived in Batavia on 18 February 1823.[1]

As an army medical officer, Siebold was posted to an artillery unit. However, he was given a room for a few weeks at the residence of the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, Baron Godert van der Capellen, to recover from an illness. With his erudition, he impressed the Governor-General, and also the director of the botanical garden at Buitenzorg (now Bogor), Caspar Georg Carl Reinwardt.[1] These men sensed in Siebold a worthy successor to Engelbert Kaempfer and Carl Peter Thunberg, two former resident physicians at Dejima, a Dutch trading post in Japan, the former of whom was the author of _Flora Japonica.[1] The Batavian Academy of Arts and Sciences soon elected Siebold as a member.

On 28 June 1823, after only a few months in the Dutch East Indies, Siebold was posted as resident physician and scientist to Dejima, a small artificial island and trading post at Nagasaki, and arrived there on 11 August 1823.[1] During an eventful voyage to Japan he only just escaped drowning during a typhoon in the East China Sea.[1] As only a very small number of Dutch personnel were allowed to live on this island, the posts of physician and scientist had to be combined. Dejima had been in the possession of the Dutch East India Company (known as the VOC) since the 17th century, but the Company had gone bankrupt in 1798, after which a trading post was operated there by the Dutch state for political considerations, with notable benefits to the Japanese.

The European tradition of sending doctors with botanical training to Japan was a long one. Sent on a mission by the Dutch East India Company, Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716), a German physician and botanist who lived in Japan from 1690 until 1692, ushered in this tradition of a combination of physician and botanist. The Dutch East India Company did not, however, actually employ the Swedish botanist and physician Carl Peter Thunberg (1743–1828), who had arrived in Japan in 1775.

Japanese scientists invited Siebold to show them the marvels of western science, and he learned in return through them much about the Japanese and their customs. After curing an influential local officer, Siebold gained the permission to leave the trade post. He used this opportunity to treat Japanese patients in the greater area around the trade post. Siebold is credited with the introduction of vaccination and pathological anatomy for the first time in Japan.[2]

In 1824, Siebold started a medical school in Nagasaki, the Narutaki-juku,[3] that grew into a meeting place for around fifty students. They helped him in his botanical and naturalistic studies. The Dutch language became the lingua franca (common spoken language) for these academic and scholarly contacts for a generation, until the Meiji Restoration.

His patients paid him in kind with a variety of objects and artifacts that would later gain historical significance. These everyday objects later became the basis of his large ethnographic collection, which consisted of everyday household goods, woodblock prints, tools and hand-crafted objects used by the Japanese people.

During his stay in Japan, Siebold "lived together" with Kusumoto Taki (楠本滝),[1] who gave birth to their daughter Kusumoto (O-)Ine in 1827.[1] Siebold used to call his wife "Otakusa" (probably derived from O-Taki-san) and named a Hydrangea after her. Kusumoto Ine eventually became the first Japanese woman known to have received a physician's training and became a highly regarded practicing physician and court physician to the Empress in 1882. She died at court in 1903.[1][4]

Studies of Japanese fauna and flora

[edit]

His main interest, however, focused on the study of Japanese fauna and flora. He collected as much material as he could. Starting a small botanical garden behind his home (there was not much room on the small island) Siebold amassed over 1,000 native plants.[1] In a specially built glasshouse he cultivated the Japanese plants to endure the Dutch climate. Local Japanese artists like Kawahara Keiga drew and painted images of these plants, creating botanical illustrations but also images of the daily life in Japan, which complemented his ethnographic collection. He hired Japanese hunters to track rare animals and collect specimens. Many specimens were collected with the help of his Japanese collaborators Keisuke Ito (1803–1901), Mizutani Sugeroku (1779–1833), Ōkochi Zonshin (1796–1882) and Katsuragawa Hoken (1797–1844), a physician to the shōgun. As well, Siebold's assistant and later successor, Heinrich Bürger (1806–1858), proved to be indispensable in carrying on Siebold's work in Japan.

Siebold first introduced to Europe such familiar garden-plants as the Hosta and the Hydrangea otaksa. Unknown to the Japanese, he was also able to smuggle out germinative seeds of tea plants to the botanical garden _Buitenzorg in Batavia. Through this single act, he started the tea culture in Java, a Dutch colony at the time. Until then Japan had strictly guarded the trade in tea plants. Remarkably, in 1833, Java already could boast a half million tea plants.

He also introduced Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica, syn. Fallopia japonica), which has become a highly invasive weed in Europe and North America.[5] All derive from a single female plant collected by Siebold.

During his stay at Dejima, Siebold sent three shipments with an unknown number of herbarium specimens to Leiden, Ghent, Brussels and Antwerp. The shipment to Leiden contained the first specimens of the Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus) to be sent to Europe.

In 1825 the government of the Dutch-Indies provided him with two assistants: apothecary and mineralogist Heinrich Bürger (his later successor) and the painter Carl Hubert de Villeneuve. Each would prove to be useful to Siebold's efforts that ranged from ethnographical to botanical to horticultural, when attempting to document the exotic Eastern Japanese experience. De Villeneuve taught Kawahara the techniques of Western painting.

Reportedly, Siebold was not the easiest man to deal with. He was in continuous conflict with his Dutch superiors who felt he was arrogant. This threat of conflict resulted in his recall in July 1827 back to Batavia. But the ship, the Cornelis Houtman, sent to carry him back to Batavia, was thrown ashore by a typhoon in Nagasaki bay. The same storm badly damaged Dejima and destroyed Siebold's botanical garden. Repaired, the Cornelis Houtman was refloated. It left for Batavia with 89 crates of Siebold's salvaged botanical collection, but Siebold himself remained behind in Dejima.

In 1826 Siebold made the court journey to Edo. During this long trip he collected many plants and animals. But he also obtained from the court astronomer Takahashi Kageyasu several detailed maps of Japan and Korea (written by Inō Tadataka), an act strictly forbidden by the Japanese government.[1] When the Japanese discovered, by accident, that Siebold had a map of the northern parts of Japan, the government accused him of high treason and of being a spy for Russia.[1]

The Japanese placed Siebold under house arrest and expelled him from Japan on 22 October 1829.[1] Satisfied that his Japanese collaborators would continue his work, he journeyed back on the frigate Java to his former residence, Batavia, in possession of his enormous collection of thousands of animals and plants, his books and his maps.[1] The botanical garden of _Buitenzorg would soon house Siebold's surviving, living flora collection of 2,000 plants. He arrived in the Netherlands on 7 July 1830. His stay in Japan and Batavia had lasted for a period of eight years.[1]

Philipp Franz von Siebold arrived in the Netherlands in 1830, just at a time when political troubles erupted in Brussels, leading soon to Belgian independence. Hastily he salvaged his ethnographic collections in Antwerp and his herbarium specimens in Brussels and took them to Leiden, helped by Johann Baptist Fischer.[1] He left behind his botanical collections of living plants that were sent to the University of Ghent.[1] The consequent expansion of this collection of rare and exotic plants led to the horticultural fame of Ghent. In gratitude the University of Ghent presented him in 1841 with specimens of every plant from his original collection.

Siebold settled in Leiden, taking with him the major part of his collection.[1] The "Philipp Franz von Siebold collection", containing many type specimens, was the earliest botanical collection from Japan. Even today, it still remains a subject of ongoing research, a testimony to the depth of work undertaken by Siebold. It contained about 12,000 specimens, from which he could describe only about 2,300 species. The whole collection was purchased for a handsome amount by the Dutch government. Siebold was also granted a substantial annual allowance by the Dutch King William II and was appointed Advisor to the King for Japanese Affairs. In 1842, the King even raised Siebold to the nobility as an esquire.

The "Siebold collection" opened to the public in 1831. He founded a museum in his home in 1837. This small, private museum would eventually evolve into the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden.[6] Siebold's successor in Japan, Heinrich Bürger, sent Siebold three more shipments of herbarium specimens collected in Japan. This flora collection formed the basis of the Japanese collections of the National Herbarium of the Netherlands[7] in Leiden, while the zoological specimens Siebold collected were kept by the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie (National Museum of Natural History) in Leiden, which later became Naturalis. Both institutions merged into Naturalis Biodiversity Center in 2010, which now maintains the entire natural history collection that Siebold brought back to Leiden.[8]

In 1845 Siebold married Helene von Gagern (1820–1877), they had three sons and two daughters.

During his stay in Leiden, Siebold wrote Nippon in 1832, the first part of a volume of a richly illustrated ethnographical and geographical work on Japan. The Archiv zur Beschreibung Nippons also contained a report of his journey to the Shogunate Court at Edo.[1] He wrote six further parts, the last ones published posthumously in 1882; his sons published an edited and lower-priced reprint in 1887.[1]

Coloured plate of Cephalotaxus pedunculata in _Flora Japonica, by Philipp Franz von Siebold and Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini

The _Bibliotheca Japonica appeared between 1833 and 1841. This work was co-authored by Joseph Hoffmann and Kuo Cheng-Chang, a Javanese of Chinese extraction, who had journeyed along with Siebold from Batavia.[1] It contained a survey of Japanese literature and a Chinese, Japanese and Korean dictionary.[1] Siebold's writing on Japanese religion and customs notably shaped early modern European conceptions of Buddhism and Shinto; he notably suggested that Japanese Buddhism was a form of Monotheism.[9]

The zoologists Coenraad Temminck (1777–1858), Hermann Schlegel (1804–1884), and Wilhem de Haan (1801–1855) scientifically described and documented Siebold's collection of Japanese animals.[1] The _Fauna Japonica, a series of monographs published between 1833 and 1850, was mainly based on Siebold's collection, making the Japanese fauna the best-described non-European fauna – "a remarkable feat". A significant part of the _Fauna Japonica was also based on the collections of Siebold's successor on Dejima, Heinrich Bürger.

Siebold wrote his _Flora Japonica in collaboration with the German botanist Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini (1797–1848). It first appeared in 1835, but the work was not completed until after his death, finished in 1870 by F.A.W. Miquel (1811–1871), director of the Rijksherbarium in Leiden. This work expanded Siebold's scientific fame from Japan to Europe.

From the Hortus Botanicus Leiden – the botanical garden of Leiden – many of Siebold's plants spread to Europe and from there to other countries. Hosta and Hortensia, Azalea, and the Japanese butterbur and the coltsfoot as well as the Japanese larch began to inhabit gardens across the world.

International endeavours

[edit]

Coat of arms of Siebold

After his return to Europe, Siebold tried to exploit his knowledge of Japan. Whilst living in Boppard, from 1852 he corresponded with Russian diplomats such as Baron von Budberg-Bönninghausen, the Russian ambassador to Prussia, which resulted in an invitation to go to St Petersburg to advise the Russian government how to open trade relations with Japan. Though still employed by the Dutch government he did not inform the Dutch of this voyage until after his return.

American Naval Commodore Matthew C. Perry consulted Siebold in advance of his voyage to Japan in 1854.[10] He notably advised Townsend Harris on how Christianity might be spread to Japan, alleging based on his time there that the Japanese "hated" Christianity.[11]

In 1858, the Japanese government lifted the banishment of Siebold. He returned to Japan in 1859 as an adviser to the Agent of the Dutch Trading Society (Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij) in Nagasaki, Albert Bauduin. After two years the connection with the Trading Society was severed as the advice of Siebold was considered to be of no value. In Nagasaki he fathered another child with one of his female servants.

In 1861 Siebold organised his appointment as an adviser to the Japanese government and went in that function to Edo. There he tried to obtain a position between the foreign representatives and the Japanese government. As he had been specially admonished by the Dutch authorities before going to Japan that he was to abstain from all interference in politics, the Dutch Consul General in Japan, J.K. de Wit, was ordered to ask Siebold's removal.[12] Siebold was ordered to return to Batavia and from there he returned to Europe.

After his return he asked the Dutch government to employ him as Consul General in Japan but the Dutch government severed all relations with Siebold who had a huge debt because of loans given to him, except for the payment of his pension.

Siebold kept trying to organise another voyage to Japan. After he did not succeed in gaining employment with the Russian government, he went to Paris in 1865 to try to interest the French government in funding another expedition to Japan, but failed.[13] He died in Munich on 18 October 1866.[1]

Plants named after Siebold

[edit]

The botanical and horticultural spheres of influence have honored Philipp Franz von Siebold by naming some of the very garden-worthy plants that he studied after him. Examples include:

Toringo Crab-Apple (flowering Malus sieboldii)

- Acer sieboldianum or Siebold's Maple: a variety of maple native to Japan

- Calanthe sieboldii or Siebold's Calanthe is a terrestrial evergreen orchid native to Japan, the Ryukyu Islands and Taiwan.

- Clematis florida var. sieboldiana (syn: C. florida 'Sieboldii' & C. florida 'Bicolor'): a somewhat difficult Clematis to grow "well" but a much sought after plant nevertheless

- Corylus sieboldiana [jp]: (Asian beaked hazel) is a species of nut found in northeastern Asia and Japan

- Dryopteris sieboldii: a fern with leathery fronds

- Hosta sieboldii of which a large garden may have a dozen quite distinct cultivars

- Magnolia sieboldii: the under-appreciated small "Oyama" magnolia

- Malus sieboldii: the fragrant Toringo Crab-Apple, (originally called Sorbus toringo by Siebold), whose pink buds fade to white

- Primula sieboldii: the Japanese woodland primula Sakurasou (Chinese/Japanese: 櫻草)

- Prunus sieboldii: a flowering cherry

- Sedum sieboldii: a succulent whose leaves form rose-like whorls

- Tsuga sieboldii: a Japanese hemlock

- Viburnum sieboldii: a deciduous large shrub that has creamy white flowers in spring and red berries that ripen to black in autumn

Animals named after Siebold

[edit]

- Enhydris sieboldii or Siebold's smooth water snake[14]

- A type of abalone, Nordotis gigantea, is known as Siebold's abalone,[15] and is prized for sushi.

- A genus of large gomphid dragonflies, Sieboldius[16]

Though he is well known in Japan, where he is called "Shiboruto-san", and although mentioned in the relevant schoolbooks, Siebold is almost unknown elsewhere, except among gardeners who admire the many plants whose names incorporate sieboldii and sieboldiana. The Hortus Botanicus in Leiden has recently laid out the "Von Siebold Memorial Garden", a Japanese garden with plants sent by Siebold. The garden was laid out under a 150-year-old Zelkova serrata tree dating from Siebold's lifetime.[17] Japanese visitors come and visit this garden, to pay their respect for him.

Sword given to Siebold by Tokugawa Iemochi on 11 November 1861, on display at the State Museum of Ethnology in Munich

Siebold Memorial Museum in Nagasaki, Japan

Although he was disillusioned by what he perceived as a lack of appreciation for Japan and his contributions to its understanding, a testimony of the remarkable character of Siebold is found in museums that honor him.

- Japan Museum SieboldHuis in Leiden, Netherlands, shows highlights from the Leiden Siebold collections in the transformed, refitted, formal, first house of Siebold in Leiden

- Naturalis Biodiversity Center, the National Museum of Natural History in Leiden, Netherlands houses the zoological and botanical specimens Siebold collected during his first stay in Japan (1823-1829). These include 200 mammals, 900 birds, 750 fishes, 170 reptiles, over 5,000 invertebrates, 2,000 different species of plants and 12,000 herbarium specimens.[18]

- The National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, Netherlands houses the large collection which Siebold brought together during his first stay in Japan (1823–1829).

- The State Museum of Ethnology in Munich, Germany, houses the collection of Philipp Franz von Siebold from his second voyage to Japan (1859–1862) and a letter of Siebold to King Ludwig I in which he urged the monarch to found a museum of ethnology at Munich. Siebold's grave, in the shape of a Buddhist pagoda, is in the _Alter Münchner Südfriedhof (Former Southern Cemetery of Munich). He is also commemorated in the name of a street and a large number of mentions in the Botanical Garden at Munich.

- A Siebold-Museum exists in Würzburg, Germany.

- Siebold-Museum on Brandenstein castle [de], Schlüchtern, Germany.

- Nagasaki, Japan, pays tribute to Siebold by housing the Siebold Memorial Museum on property adjacent to Siebold's former residence in the Narutaki neighborhood, the first museum dedicated to a non-Japanese in Japan.

His collections laid the foundation for the ethnographic museums of Munich and Leiden. Alexander von Siebold, one of his sons by his European wife, donated much of the material left behind after Siebold's death in Würzburg to the British Museum in London. The Royal Scientific Academy of St. Petersburg purchased 600 colored plates of the _Flora Japonica.

Another son, Heinrich (or Henry) von Siebold (1852–1908), continued part of his father's research. He is recognized, together with Edward S. Morse, as one of the founders of modern archaeological efforts in Japan.

- (1832–1852) Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan und dessen Neben- und Schutzländern: Jezo mit den Südlichen Kurilen, Krafto, Koorai und den Liukiu-Inseln. 7 volumes, Leiden.

- (1838) Voyage au Japon Executé Pendant les Années 1823 a 1830 – French abridged version of Nippon – contains 72 plates from Nippon, with a slight variance in size and paper. Published in twelve "Deliveries". Each "Delivery" contains 72 lithographs (plates) and each "Delivery" varies in its lithograph contents by four or five plate variations.

- Revised and enlarged edition by his sons in 1897: Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan ..., 2. veränderte und ergänzte Auflage, hrsg. von seinen Söhnen, 2 volumes, Würzburg and Leipzig.

- Translation of the part of Nippon on Korea ("Kooraï"): Boudewijn Walraven (ed.), Frits Vos (transl.), Korean Studies in Early-nineteenth century Leiden, Korean Histories 2.2, 75-85, 2010

- (1829) Synopsis Hydrangeae generis specierum Iaponicarum. In: Nova Acta Physico-Medica Academiae Caesareae Leopoldino-Carolina vol 14, part ii.

- (1835–1870) (with Zuccarini, J. G. von, editor) Flora Japonica. Leiden.

- (1843) (with Zuccarini, J. G. von) Plantaram, quas in Japonia collegit Dr. Ph. Fr. de Siebold genera nova, notis characteristicis delineationibusque illustrata proponunt. In: Abhandelungen der mathematisch-physikalischen Classe der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften vol.3, pp 717–750.

- (1845) (with Zuccarini, J. G. von) Florae Japonicae familae naturales adjectis generum et specierum exemplis selectis. Sectio prima. Plantae Dicotyledoneae polypetalae. In: Abhandelungen der mathematischphysikalischen Classe der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften vol. 4 part iii, pp 109–204.

- (1846) (with Zuccarini, J. G. von) Florae Japonicae familae naturales adjectis generum et specierum exemplis selectis. Sectio altera. Plantae dicotyledoneae et monocotyledonae. In: Abhandelungen der mathematischphysikalischen Classe der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften vol. 4 part iii, pp vol 4 pp 123–240.

- (1841) Manners and Customs of the Japanese, in the Nineteenth Century. London: Murray. 1841 – via Hathi Trust. From recent Dutch visitors of Japan and the German of Dr. Ph. Fr. von Siebold (compiled by an anonymous author, not by Siebold himself !)

The standard author abbreviation Siebold is used to indicate Philipp Franz von Siebold as the author when citing a botanical name.[19]

- Category:Taxa named by Philipp Franz von Siebold

- Bunsei – Japanese era names

- Dejima

- Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold

- Erwin Bälz

- Sakoku

- List of Westerners who visited Japan before 1868

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae E. M. Binsbergen. "Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866). Wetenschapper in de Oost" [Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866). Scientist in the East] (in Dutch). University of Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007.

- ^ Hiroyuki Odagiri & Akira Gotō (1996). Technology and Industrial Development in Japan. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 236. ISBN 0-19-828802-6.

- ^ "Edo Period".

- ^ "Unterstein.net: Siebold family".

- ^ Bailey, J.P.; Conolly, A.P. (2000). "Prize-winners to pariahs - A history of Japanese Knotweed s.l. (Polygonaceae) in the British Isles" (PDF). Watsonia. 23: 93–110. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ Willem Otterspeer (1989). Leiden Oriental Connections, 1850–1940. Studies in the History of Leiden University. Vol. 5. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 389. ISBN 978-90-04-09022-4.

- ^ "Nationaal Herbarium Nederland".

- ^ "Naturalis Biodiversity Center homepage (in English)".

- ^ Josephson, Jason (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 12–4.

- ^ John S. Sewall (1905). The Logbook of the Captain's Clerk: Adventures in the China Seas. Bangor, Maine: Chas H. Glass & Co. [reprint by Chicago: R.R. Donnelly & Sons, 1995]. p. xxxviii. ISBN 0-548-20912-X.

- ^ Josephson, Jason (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 80–2.

- ^ Herman J. Moeshart (1990). "Von Siebold's second visit to Japan". In Peter Lowe & Herman J. Moeshart (ed.). Western Interactions with Japan: Expansion, the Armed Forces & Readjustment, 1859–1956. Sandgate. pp. 13–25. ISBN 978-0-904404-84-5.

- ^ The story is told by Alphonse Daudet in the short story "L'Empereur aveugle", part of his book "Contes du lundi".

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Siebold, P.F.B.", p. 243).

- ^ "Siebold's abalone (Nordotis gigantea), disk abalone (Nordotis discus), and red sea cucumber (Holothuroidea) in Fukuoka Prefecture". JST: Science Links Japan. 2009. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ Paulson, Dennis R. (2009). Dragonflies and damselflies of the West. Princeton field guides. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12281-6.

- ^ A video introduces the Siebold Memorial garden. See video here

- ^ Parts of the Siebold natural history collection have been digitized in recent years, see Naturalis Collections portal Archived 2 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Siebold, Philipp Franz (Balthasar) von (1796–1866)". IPNI Author Details. International Plant Name Index. 2005. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

References and other literature

[edit]

Brown, Yu-jing: The von Siebold Collection from Tokugawa, Japan, pp. 1–55, British Library bl.uk

Andreas W. Daum: "German Naturalists in the Pacific around 1800: Entanglement, Autonomy, and a Transnational Culture of Expertise." In Explorations and Entanglements: Germans in Pacific Worlds from the Early Modern Period to World War I, ed. Hartmut Berghoff et al. New York, Berghahn Books, 2019, 70‒102.

Effert, Rudolf Antonius Hermanus Dominique: Royal Cabinets and Auxiliary Branches: Origins of the National Museum of Ethnology 1816–1883, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 2008. Serie: Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum van Volkenkunde, Leiden, no. 37

Friese, Eberhard: Philipp Franz von Siebold als früher Exponent der Ostasienwissenschaften. Berliner Beiträge zur sozial- und wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Japan-Forschung Bd. 15. Bochum 1983 ISBN 3-88339-315-0

Reginald Grünenberg: Die Entdeckung des Ostpols. Nippon-Trilogie, Vol. 1 Shiborto ISBN 978-3-942662-16-1, Vol. 2 Geheime Landkarten, ISBN 978-3-942662-17-8, Vol. 3 Der Weg in den Krieg, ISBN 978-3-942662-18-5, Die Entdeckung des Ostpols. Nippon-Trilogie.Gesamtausgabe ('Complete Edition'), ISBN 978-3-942662-19-2, Perlen Verlag 2014; English resume of the novel on www.east-pole.com

Richtsfeld, Bruno J.: Philipp Franz von Siebolds Japansammlung im Staatlichen Museum für Völkerkunde München. In: Miscellanea der Philipp Franz von Siebold Stiftung 12, 1996, pp. 34–54.

Richtsfeld, Bruno J.: Philipp Franz von Siebolds Japansammlung im Staatlichen Museum für Völkerkunde München. In: 200 Jahre Siebold, hrsg. von Josef Kreiner. Tokyo 1996, pp. 202–204.

Richtsfeld, Bruno J.: Die Sammlung Siebold im Staatlichen Museum für Völkerkunde, München. In: Das alte Japan. Spuren und Objekte der Siebold-Reisen. Herausgegeben von Peter Noever. München 1997, p. 209f.

Richtsfeld, Bruno J.: Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866). Japanforscher, Sammler und Museumstheoretiker. In: Aus dem Herzen Japans. Kunst und Kunsthandwerk an drei Flüssen in Gifu. Herausgegeben von dem Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln und dem Staatlichen Museum für Völkerkunde München. Köln, München 2004, pp. 97–102.

Thijsse, Gerard: Herbarium P.F. von Siebold, 1796–1866, 1999, Brill.com

Yamaguchi, T., 1997. Von Siebold and Japanese Botany. Calanus Special number I.

Yamaguchi, T., 2003. How did Von Siebold accumulate botanical specimens in Japan? Calanus Special number V.

Works by or about Philipp Franz von Siebold at the Internet Archive

Fauna Japonica – University of Kyoto

Flora Japonica – University of Kyoto

Website dedicated to the German novel Die Entdeckung des Ostpols

Siebold Huis – a museum in the house where Siebold lived in Leiden

The Siebold Museum in Würzburg

The Siebold-Museum on Brandenstein castle, Schlüchtern

Siebold's Nippon, 1897 (in German)

-

- "Siebold, Philipp Franz von". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Siebold, Philipp Franz von". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Siebold, Philipp Franz von". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.