Plácido Zuloaga (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Spanish 19th century metalworker

| Plácido Zuloaga | |

|---|---|

Plácido painted by his son, Ignacio Zuloaga Plácido painted by his son, Ignacio Zuloaga |

|

| Born | (1834-10-05)5 October 1834[1]Madrid, Spain |

| Died | 1 July 1910(1910-07-01) (aged 75)[1] |

| Known for | Damascening |

| Spouse(s) | Lucía Zamora y Zabaleta, Francisca Gil y Lete |

| Relatives | Eusebio Zuloaga (father), Daniel Zuloaga (half-brother), Ignacio Zuloaga (son) |

| Awards | Officer of the Legion of HonorCommander of the Order of Isabella the CatholicKnight of the Grand Cross of Charles III |

Plácido Maria Martin Zuloaga y Zuloaga (5 October 1834 – 1 July 1910) was a Spanish sculptor and metalworker. He is known for refining damascening, a technique that involves inlaying gold, silver, and other metals into an iron surface, creating an intricate decorative effect. Zuloaga came from a family of Basque metalworkers. He was the son of damascening pioneer Eusebio Zuloaga, the half-brother of the artist Daniel Zuloaga, and the father of the painter Ignacio Zuloaga. Taking over his father's armaments factory, he adapted it to make art pieces which he exhibited at international fairs, winning multiple awards.

His notable works include the altar for the Sanctuary of St. Ignatius at Loyola, the Fonthill Casket (an iron cassone with intricate decoration inside and out), and a monumental sarcophagus for the Prime Minister of Spain, Juan Prim. For twenty years, Zuloaga made works for the English collector Alfred Morrison. Many of those are now in the private collection of the British-Iranian scholar and philanthropist Nasser D. Khalili. Zuloaga trained many other artisans in his workshop, and Eibar continued as a centre of a damascening after his death.

Plácido Zuloaga was born 5 October 1834 in Madrid to Antonia and Eusebio Zuloaga.[1] He was the brother of Daniel Zuloaga, a painter and ceramic artist.[1] His father was the director of the Spanish Royal Armoury and a pioneer of damascening.[1] The Zuloaga family had been producing armaments at a workshop in Eibar in the Basque country as far back as 1596.[2] Plácido learned in his father's workshop from an early age.[1] At fourteen, he visited Paris where he learned from the armourer Lepage. Then in Dresden he studied under the sculptors Antoine-Louis Barye and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux.[1]

In 1867 his father let him take over administration of the family factory in Eibar.[1] It is thought that he had already been carrying out his father's commissions for a decade at this point.[3] The workshop's royal commissions ended in 1868 when Queen Isabella II was exiled and Eusebio lost his position in the royal household.[4] Plácido contacted the English art collector Alfred Morrison, heir to a textile fortune, whom he had met at the 1862 International Exhibition in South Kensington, London.[4] Over a twenty-year period, Zuloaga and his workshop worked almost exclusively for Morrison,[4] adapting the factory to make damascened art works rather than armaments.[1]

Damascening involves indenting the iron surface, then pressing fine gold wire and heating the surface so that the gold forms a solid shape.[5] Whereas modern damascening uses acid etching to create the indentations, the Zuloagas did so with hand tools.[6] The younger Zuloaga refined his father's technique for roughening the surface of the iron, adding fine wires of gold and silver, then hammering the wires so that they joined together. Other hand tools were then used to impress designs onto the metal.[6] Zuloaga worked when gold was relatively abundant, and his works make greater use of it than later Spanish damascene.[7] His objects are so delicate they would be damaged by ordinary use as containers. Zuloaga's goal was beauty rather than practical utility.[8] To serve as references for his workshop, he collected sculptures, paintings, and plaster casts of armour pieces.[9] From 1860 to 1890, Zuloaga trained more than 200 artists in damascening.[10]

Zuloaga was skilled in all the techniques used by metalworkers of his time, including forging, relief chiselling, engraving, drawing and enamelling.[10] In order to create his most ambitious works in a reasonable time, he led a team of specialist artisans who carried out his designs, each object being produced by eight to twelve individuals.[10]

The Fonthill Casket: forged iron cassone, 1871

More than a hundred pieces of Spanish damascened metalwork, including 22 signed by Zuloaga, have been collected by the British-Iranian scholar and philanthropist Nasser D. Khalili, forming the Khalili Collection of Spanish Damascene Metalwork.[11] Included in these are the Fonthill Casket, a 201-centimetre-wide (79 in) iron cassone with gold and silver damascening, decorated with white enamel ornament in black.[12] Its artistic and decorative intent is revealed by it being elaborately decorated on the inside as well as out.[13] Commissioned by Alfred Morrison, it acquired its name from Fonthill manor, Morrison's family home. Zuloaga and his specialists took two years to construct the casket,[12] which was described by The Magazine of Art in 1879 as "a triumph of skilled workmanship".[8] Also commissioned by Morrison are a pair of amphora-shaped urns, 108 centimetres (43 in) high, from 1878 whose style imitated the medieval Alhambra vases.[14] Covered in intricate Hispano-Arabic decoration, possibly drawn from contemporary engravings of a specific Alhambra vase, these were exhibited in Paris before delivery to Morrison.[14]

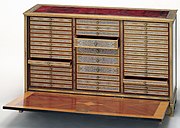

A writing desk dated 1884–1885 has 44 drawers in a wooden case, each with enamelled floral patterns and a damascened metal button-pull.[15] Not a woodworker himself, Zuloaga subcontracted out the preparation of the wood and veneer.[15] A 47.3-centimetre-high (18.6 in) iron shrine dated 1880 recalls Gothic architecture in its overall shape, but the intricate damascened decoration is more suggestive of Art Nouveau.[16] It contains a cast silver figure of the Virgin and Child in a Gothic style.[16] Other objects signed by Zuloaga include a revolver,[17] snuff boxes, caskets, and containers of various dimensions.[18]

Around 1872, Zuloaga's workshop was commissioned to make the monumental sarcophagus for General Juan Prim. Work began in Eibar, but due to the civil war of 1873 he moved his workshop across to the border to Saint-Jean-de-Luz in France where the work was completed. Prim's tomb now resides in the cemetery at Reus.[19] Around 1900, Zuloaga was commissioned by the Society of Jesus to construct an altar for the Sanctuary of St. Ignatius at Loyola. This was the last major project that he completed, referred to sometimes as his "posthumous" work, although in fact the altar was completed and installed at Loyola in 1909 while he was still alive.[20] It was described by Pedro Celaya in 1981 as "one of the greatest works ... that has been produced in Eibar."[21]

Pair of iron urns, before 1878

Iron shrine with virgin and child, 1880

Writing or document desk, 1884-85

Recognition and legacy

[edit]

Iron table clock, circa 1880

Zuloaga died in Madrid at the age of 76 on 1 July 1910 and was buried at Canillejas.[10] Several of his trainees continued as noted artists, and Eibar continued as the centre of Spanish damascene production until the Spanish Civil War.[10]

During his life, Zuloaga was awarded the Officer of the French Legion of Honor, Knight Commander of the Order of Isabel the Catholic, Knight of the Great Cross of Charles III, Knight of the Great Cross of the Lion and Sword of Sweden, Cross of King Leopold of Belgium, Knight of the Portuguese Order of St. James, Grand Cross of Santiago of Portugal, and Knight of the Order of Maria Teresa of Austria.[1][10] He won many gold and silver medals at national and international exhibitions.[10]

The critical reception of Zuloaga's art, and of Spanish damascened metalwork generally, has changed greatly over time. In 1872, the Keeper of Art Collections in the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum) wrote that a Léonard Morel-Ladeuil vase decorated by Zuloaga "will be regarded as one of the greatest Art productions of the century".[22] An 1879 article in the Magazine of Art said that his works showed a patience and effort that "take one into an era when the fine arts producer devoted himself solely to the cause of his métier, apart from the commercial considerations of time, trouble and expense."[23] Early twentieth-century art critics took a more negative view of the Zuloaga family's works, but a new wave of interest and critical appreciation emerged in the last decades of that century.[22] Nasser Khalili, who writes that "Spain [has] always led the West in its beauty and quality of its damascene production", describes Zuloaga as "the supreme damascener of [his] family".[24]

Bronze gilt and enamelled casket, 1891–1892

Zuloaga exhibited his works at the 1855 Paris International Exposition (where he was awarded a Medal of Honour) and at the Madrid and Brussels International exhibitions of 1856, then at the Great London Exposition of 1862.[1]

More recently, his works in the Khalili Collections have featured in a multiple exhibitions.[25] "Plácido Zuloaga: Spanish Treasures from The Khalili Collection" was held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London from May 1997 to January 1998. "El Arte y Tradición de los Zuloaga: Damasquinado Español de la Colección Khalili" toured Spain during 2000 and 2001, exhibiting in the Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao; Alhambra Palace, Granada; and Real Fundacion de Toledo. In 2003, "Plácido Zuloaga: Meisterwerke in gold, silber und eisen damaszener–schmiedekunst aus der Khalili-Sammlung" exhibited at the Roemer und Pelizaeus Museum in Germany. "Metal Magic: Spanish Treasures from the Khalili Collection" was exhibited from November 2011 to April 2012 at the Auberge de Provence in Malta.[25]

With his first wife Lucía Zamora y Zabaleta, he had ten children, five of whom survived to adulthood, including Ignacio Zuloaga, who would become a noted painter.[1] After Lucia died in 1900, he married Francisca Gil y Lete.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Plácido Zuloaga y Zuloaga | Real Academia de la Historia". dbe.rah.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Lavin 1997, p. 41.

- ^ Lavin 1997, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Lavin, James. "Catalogue note". Sothebys.com. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Lavin 1997, p. 45.

- ^ a b Larrañaga, Ramiro "Damascene as part of the Engraver's Art" in Lavin 1997, p. 37

- ^ Larrañaga, Ramiro "Damascene as part of the Engraver's Art" in Lavin 1997, p. 38

- ^ a b Lavin 1997, p. 57.

- ^ Lavin 1997, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lavin 1997, p. 63.

- ^ "Spanish Damascene Metalwork". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b Lavin 1997, p. 71.

- ^ Lavin 1997, pp. 59, 71.

- ^ a b Lavin 1997, p. 83.

- ^ a b Lavin 1997, p. 108.

- ^ a b Lavin 1997, p. 104.

- ^ Lavin 1997, p. 102.

- ^ Lavin 1997, pp. 90–114.

- ^ Lavin 1997, p. 58.

- ^ Lavin 1997, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Celaya, P.; Larrañaga, R.; and San Martin, J. (1981) El damasquinado de Eibar p.100 quoted in Lavin 1997, p. 63

- ^ a b Blair, Claude "Introduction" in Lavin 1997, p. 9

- ^ "Treasure Houses of Art-II" The Magazine of Art (1879) pp.206–8 quoted in Lavin 1997, p. 57

- ^ Khalili, Nasser D. "Foreword" in Lavin 1997, p. 8

- ^ a b "The Eight Collections". nasserdkhalili.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0. Text taken from The Khalili Collections, Khalili Foundation.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0. Text taken from The Khalili Collections, Khalili Foundation.

- Lavin, James D. (1997). The art and tradition of the Zuloagas : Spanish damascene from the Khalili Collection. Oxford: Khalili Family Trust in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum. ISBN 1-874780-10-2. OCLC 37560664.

- Williams, Haydn (2016). A Moresque fantasy : Plácido Zuloaga: an 'Alhambra' vase. Sinai and Sons. London. ISBN 978-0-9576995-4-0. OCLC 982266094.

{{[cite book](/wiki/Template:Cite%5Fbook "Template:Cite book")}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Martinez Artola, Alberto. "Zuloaga Zuloaga, Plácido - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Dakers, Caroline (2011). A genius for money : business, art and the Morrisons. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 241–245. doi:10.12987/9780300184594-021. ISBN 978-0-300-18459-4. OCLC 811405739. S2CID 246145937.

- San Martín, Juan; Larrañaga, Ramiro; Celaya, Pedro (1981). El damasquinado de Eibar (in Spanish). Eibar: Museo de Armas. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2021.