SS Boniface (1928) (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1928 Steam Cargo Ship in United Kingdom

| History | |

United Kingdom United Kingdom |

|

| Name | Boniface (1928–49) Browning (1949–51) Sannicola (1951) Mizuho Maru (1951–61) |

| Namesake | Saint Boniface (1928–49) Robert Browning (1949–51) Sannicola (1951) Mizuho (1951–61) |

| Owner |  Booth Line (1928–49) Lamport and Holt (1949–51) Cia de Nav Niques (1951) Muko Kisen KK (1951–61) Booth Line (1928–49) Lamport and Holt (1949–51) Cia de Nav Niques (1951) Muko Kisen KK (1951–61) |

| Port of registry | Liverpool |

| Route | Liverpool – Brazil |

| Builder | Hawthorn, Leslie & Co |

| Yard number | 554 |

| Launched | 4 May 1928 |

| Completed | July 1928 |

| Identification | UK official number 149685 call sign GNSK (1934 onward)     |

| Fate | Scrapped 1961 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | cargo liner |

| Tonnage | 4,877 GRT tonnage under deck 4,453 3,030 NRT |

| Length | 407.8 ft (124.3 m) |

| Beam | 53.8 ft (16.4 m) |

| Draught | 25 ft 2+1⁄2 in (7.68 m) |

| Depth | 26.0 ft (7.9 m) |

| Decks | 2 |

| Installed power | 668 NHP |

| Propulsion | triple-expansion steam engine low-pressure steam turbine single screw |

| Speed | 12.5 knots (23.2 km/h) |

| Sensors and processing systems | wireless direction finding |

| Notes | sister ships: Basil, Benedict |

SS Boniface was a UK-built steam cargo liner that was launched in 1928 and scrapped in 1961. She spent most of her career with Booth Line. After Alfred Booth and Company sold its shipping line in 1946 the ship changed hands three times and was successively named Browning, Sannicola and Muzuho Maru.

Boniface is notable for being the first UK-built ship to combine a triple-expansion steam engine and low-pressure steam turbine driving the same propeller shaft by the Bauer-Wach system.

Hawthorn, Leslie and Company built Boniface on Tyneside. She had two sister ships: Basil and Benedict. Hawthorn, Leslie built Basil four months before Boniface. Cammell, Laird and Company built Benedict in 1930.[1] Neither Basil nor Benedict had a Bauer-Wach turbine system.

All three sisters were built for Alfred Booth and Company, which named all of its ships after Christian saints.[2] Saint Boniface was an English missionary bishop and apostle to Germania early in the eighth century AD. Booth Line had a previous Boniface, which the German submarine SM U-53 had sunk in 1917.[3]

Booth Line lost nine ships in the First World War.[3] But after the 1918 Armistice shipbuilding costs rose rapidly, so Booth Line did not order any new ships until the late 1920s. Nor did it buy any second-hand ships until 1927, when it acquired a German-built cargo ship that it renamed Dominic.[1]

Basil and Boniface were Booth Line's first order for new ships for a decade. They became the start of a fleet renewal programme that continued until 1935.[4]

Combining piston and turbine steam power

[edit]

In 1908 William Denny and Brothers built Otaki, the first steamship to be propelled by a combination of piston and turbine steam power. She had three propellers. Her port and starboard propeller shafts were each driven by a triple-expansion engine. Her middle propeller shaft was driven by a low-pressure turbine. Steam exhausted from the low pressure cylinders of her port and starboard reciprocating engines powered her central turbine.[5]

Combining triple-expansion piston engines with a turbine gave Otaki fuel efficiency and power output similar to a quadruple-expansion engine, but without the weight, complexity and vibration of the largest, lowest-pressure cylinder. Other shipbuilders started to combine triple-expansion engines with a low-pressure turbine. Harland and Wolff adopted the same arrangement on a far larger scale for White Star Line's Olympic, Titanic and Britannic.[5]

Difficulties with sharing the same propeller shaft

[edit]

But the system pioneered in Otaki was applicable only to ships with three propellers. Most ships have only one or two propellers. On such ships an exhaust turbine would have to drive the same shaft as a reciprocating engine.

Piston steam engines run efficiently at relatively low shaft speeds, but turbines run efficiently at relatively high shaft speeds. When Otaki was going full ahead, her reciprocating engines ran at 103 rpm and her turbine ran at 227 rpm.[6]

Also piston engines deliver power unevenly and can vibrate, but turbines run smoothly and deliver power evenly. If the two types of engine drove the same shaft, the piston engine would impede the running of the turbine.

The Bauer-Wach system

[edit]

Dr Gustav Bauer, 1871–1953, inventor of the Bauer-Wach exhaust turbine system

Marine screw propellers run better at speeds much slower than steam turbines. But early turbine ships used direct drive, which was too fast and hampered their low-speed operation. In about 1911 reduction gearing was introduced for marine turbines. This allowed turbines to run at a high speed while driving a propeller shaft at a low speed.[5] Thereafter all marine turbines were installed with either single- or double-reduction gearing.

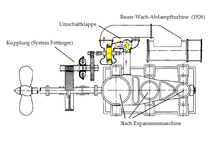

In 1926 two German engineers, Dr Gustav Bauer and Hans Wach, combined double reduction gearing with a fluid coupling between the intermediate gears to allow a low-pressure turbine to drive the same shaft as a piston engine. The fluid coupling absorbed enough of the piston engine's uneven power delivery to let the turbine run smoothly.[7]

Plan of a triple-expansion piston engine with Bauer-Wach exhaust turbine system. Yellow marks the turbine rotor and the diverter valve. The Föttinger fluid coupling is between the intermediate gears.

Turbines do not run in reverse. Bauer and Wach fitted a diverter valve on the pipe taking steam from the low-pressure cylinder to the turbine. For the ship to go astern, the valve was switched to bypass the turbine and send the exhaust steam straight to the condenser. The piston engine could then be reversed, and the turbine would idle on its shaft.

Bauer and Wach worked for the shipbuilder Joh. C. Tecklenborg in Bremerhaven, which with other shipbuilders founded the Deschimag partnership in 1926. The fluid coupling had been developed in 1905 by Dr Hermann Föttinger of AG Vulcan Stettin under Dr Bauer's direction. AG Vulcan was another partner in Deschimag.[7]

In 1928 Tecklenborg cased trading and the Bauer-Wach manufacturing rights passed to AG Weser, the largest partner in Deschimag. AG Weser licensed other marine engine manufacturers to build engines on the Bauer-Wach system.[7]

Details of Boniface

[edit]

Aerial view of Hawthorn, Leslie & Co's shipyard in Hebburn

Hawthorn Leslie and Company built Basil and Boniface on the River Tyne at Hebburn, County Durham. The combined price of the two ships to Booth Line was £218,000.[1]

Boniface was launched on 4 May 1928 and completed that July. She was 407.8 ft (124.3 m) long, had a beam of 53.8 ft (16.4 m) and draught of 25 ft 2+1⁄2 in (7.68 m). Her tonnages were 4,877 GRT and 3,030 NRT.[8]

Boniface had nine corrugated furnaces with a combined grate area of 195 square feet (18 m2). The furnaces heated three single-ended boilers with a combined heating surface of 8,859 square feet (823 m2). The boilers supplied steam at 215 lbf/in2 to one three-cylinder triple-expansion engine.[8]

Steam exhausted from the low-pressure cylinder of the piston engine passed through a diverter valve to a steam turbine. Via double-reduction gearing and a Föttinger fluid coupling the turbine drove the same shaft as the piston engine.

Boniface's sister ship Basil, built only four months earlier, had exactly the same piston engine but without the Bauer-Wach turbine and coupling system. Basil's three-cylinder engine was rated at 600 NHP. Boniface's combined piston and turbine powerplant was rated at 668 NHP,[4][8] which was 11 per cent more than Basil's[9] and gave her a speed of 12.5 knots (23.2 km/h).[10]

Boniface's UK official number was 149685. Lloyd's Register does not record code letters for her for the years 1930–33.[11] In 1934 there was an international revision of ship identification and Boniface was given the call sign GNSK.[8]

Booth Line ran cargo liner services between Liverpool and Brazil.

In the Second World War Boniface seems to have sailed mostly unescorted. The only convoy records in which she appears are a few short-distance ones. WN 115 from the Clyde around the north of Scotland to Methil on the Firth of Forth in April 1941,[12] EC 20 from Southend-on-Sea to the Clyde in May 1941,[13] EN 57 from Methil to Oban in March 1942,[14] OS 34 from Liverpool to Freetown in Sierra Leone in July 1942[15] and ST 30A from Freetown to Sekondi-Takoradi on the Gold Coast in August 1942.[16]

In April 1946 Alfred Booth and Company sold its shipping interests to Vestey Group, which owned Blue Star Line and had taken over Lamport and Holt in 1944. In 1949 Boniface was transferred to Lamport and Holt.[17] L&H named its ships after distinguished historical figures, and since 1919 had given many of its cargo ships names beginning with "B".[18] Boniface was renamed Browning[9][17] after the 19th-century poet Robert Browning.

In 1951 Lamport and Holt sold Browning to Compañia de Naviera Niques of Panama, who renamed her Sannicola. But later that year Niques sold Sannicola to Muko Kisen KK of Japan, who renamed her Mizuho Maru.[9][17]

On 28 February 1961 Mizuho Maru arrived in Mukaishima, Hiroshima to be scrapped.[9][17]

- ^ a b c John 1959, p. 139.

- ^ John 1959, p. 53.

- ^ a b John 1959, p. 113.

- ^ a b John 1959, p. 190.

- ^ a b c Dean, FE (28 July 1936). "Steam Turbine Engines". Shipping Wonders of the World. 1 (25). Amalgamated Press: 787–791. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ Allen, Tony; Vleggeert, Nico (10 March 2014). "SS Otaki (+1917)". Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b c "Gustav Bauer-Schlichtegroll". The Engineer. 8 January 1954. Retrieved 20 October 2020 – via Grace's Guide to British Industrial History.

- ^ a b c d Lloyd's Register, Steamers and Motor Ships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1934. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Basil". Tyne Built Ships. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "Boniface". Tyne Built Ships. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Lloyd's Register, Steamers and Motor Ships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1933. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy WN.115". WN Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy EC.20". EC Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy EN.57 (series 2)". EN Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy OS.34". OS/KMS Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy ST.30A". ST Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Heaton 2004, p. 115.

- ^ Heaton 2004, p. 69.

- Heaton, Paul M (2004). Lamport & Holt Line. Abergavenny: PM Heaton Publishing. ISBN 1-872006-16-7.

- John, AH (1959). A Liverpool Merchant House. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.