Stanford White (original) (raw)

American architect (1853–1906)

This article is about the architect. For the sportsman, see Sanford White.

| Stanford White | |

|---|---|

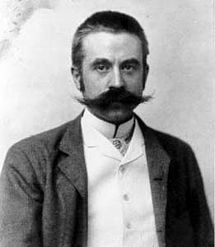

Photograph of White by George Cox, c. 1892 Photograph of White by George Cox, c. 1892 |

|

| Born | (1853-11-09)November 9, 1853New York, New York, U.S. |

| Died | June 25, 1906(1906-06-25) (aged 52)New York, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse | Bessie Springs Smith (m. 1884) |

| Children | Lawrence Grant White |

| Parent(s) | Alexina Black MeaseRichard Grant White |

| Buildings | Rosecliff, Newport, RIMadison Square Garden II, NYCWashington Square Arch, NYCNew York Herald Building, NYCSavoyard Centre, DetroitLovely Lane Methodist Church, BaltimoreRhode Island State House, ProvidenceUniversity of Virginia Rotunda |

| Signature | |

|

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect and a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, one of the most significant Beaux-Arts firms at the turn of the 20th century. White designed many houses for the wealthy, in addition to numerous civic, institutional and religious buildings. His temporary Washington Square Arch was so popular that he was commissioned to design a permanent one. White's design principles embodied the "American Renaissance".

In 1906, White was murdered during a musical performance at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. His killer, Harry Kendall Thaw, was a wealthy but mentally unstable heir of a coal and railroad fortune who had become obsessed by White's alleged drugging and rape of, and subsequent relationship with, the woman who was to become Thaw's wife, Evelyn Nesbit, which had started when she was aged 16. At the time of White's killing, Nesbit was a famous fashion model. With the public nature of the killing and elements of a sex scandal among the wealthy, the resulting trial of Thaw was dubbed the "Trial of the Century" by contemporary reporters.[1][2] Thaw was ultimately found not guilty by reason of insanity.[3]

Early life and training

[edit]

Stanford White was born in New York City in 1853, the son of Richard Grant White, a Shakespearean scholar, and Alexina Black (née Mease) (1830–1921). White's father was a dandy and Anglophile with little money but many connections to New York's art world, including the painter John LaFarge, the stained-glass artist Louis Comfort Tiffany and the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted.[4]

White had no formal architectural training; like many other architects at the time, he learned on the job as an apprentice. Beginning at age 18, he worked for six years as the principal assistant to Henry Hobson Richardson, known for his personal style (often called "Richardsonian Romanesque") and considered by many to have been the greatest American architect of his day.[4]

In 1878, White embarked on a year and a half tour of Europe to learn about historical styles and trends. When he returned to New York in September 1879, he joined two young architects, Charles Follen McKim and William Rutherford Mead, to form the firm of McKim, Mead and White. As part of the partnership, the three agreed to credit all of the firm's designs as the work of the collective firm, not to be attributed to any individual architect.[4]

In 1884, White married 22-year-old Bessie Springs Smith, daughter of J. Lawrence Smith. She was from a socially prominent Long Island family. Her ancestors had settled in what became Suffolk County in the colonial era, and the town of Smithtown was named for them. The White couple's estate, Box Hill, was both a home and a showplace for the luxe design aesthetic which White offered to prospective wealthy clients. Their son, Lawrence Grant White, was born in 1887.[5]

McKim, Mead and White

[edit]

Commercial and civic projects

[edit]

William Rutherford Mead, Charles Follen McKim and Stanford White

In 1889, White designed the triumphal arch at Washington Square, which, according to White's great-grandson, architect Samuel G. White, is the structure for which White should be best remembered. White was director of the Washington Centennial celebration. His temporary triumphal arch was so popular, that money was raised to construct a permanent version.[4]

Elsewhere in New York City, White designed the Villard Houses (1884), the second Madison Square Garden (1890, demolished in 1925),[6] the Cable Building at 611 Broadway (1893),[7] the baldechin (1888 to mid-1890s)[8] and altars of Blessed Virgin[9] and St. Joseph[10] (both completed in 1905) at St. Paul the Apostle Church, the New York Herald Building (1894; demolished 1921), and the IRT Powerhouse on 11th Avenue and 58th Street.

White also designed the Bowery Savings Bank Building at the intersection of the Bowery and Grand Street (1894), Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square, the Lambs Club Building, the Century Club, Madison Square Presbyterian Church, as well as the Gould Memorial Library (1900), built for New York University's Bronx campus but now part of Bronx Community College. It is also the site of the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.

White designed churches, residential estates, and other major works beyond New York City, such as:

- Elberon Memorial Church, erected 1886 as a memorial to Moses Taylor Elberon, New Jersey.

- The First Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore, Maryland (1887), now Lovely Lane United Methodist Church.

- The Cosmopolitan Building, a three-story Neo-classical Revival building topped by three small domes, built in Irvington, New York, in 1895 as headquarters of Cosmopolitan Magazine.

- Cocke, Rouss, and Cabell halls at the University of Virginia. In 1889, he reconstructed the university's Rotunda, three years after it had burned down. (In 1976, his work was changed to restore Thomas Jefferson's original design of the Rotunda for the United States Bicentennial.)

- The Blair Mansion at 7711 Eastern Avenue in Silver Spring, Maryland (1880). In the early 21st century, it was being used as commercial space, for a violin store.[11]

- The Boston Public Library, on Copley Square, Boston, Massachusetts.

- The Benjamin Walworth Arnold House and Carriage House (1902) in Albany, New York.

- He helped design Nikola Tesla's Wardenclyffe Tower, which was to be his last design.

White designed several clubhouses that became centers for New York society, and which still stand: the Century, Colony, Harmonie, Lambs, Metropolitan, and The Players clubs. He designed two golf clubhouses. His Shinnecock Hills Golf Clubhouse design in Suffolk County on the South Shore is said to be the oldest golf clubhouse in the United States, and has been designated as a golf landmark. Palmetto Golf Club in Aiken, South Carolina boasts the second. It was completed in 1902. His clubhouse for the Atlantic Yacht Club, built in 1894 overlooking Gravesend Bay, burned down in 1934.

Sons of society families resided in White's St. Anthony Hall Chapter House at Williams College; the building is now used for college offices.[12]

Residential properties

[edit]

The Gilded Age mansion Rosecliff, Newport RI, built between 1898 and 1902

In the division of projects within the firm, the sociable and gregarious White landed the most commissions for private houses.[13] His fluent draftsmanship helped persuade clients who were not attuned to a floorplan. He could express the mood of a building he was designing.

Many of White's Long Island mansions have survived. Harbor Hill was demolished in 1947, originally set on 688 acres (2.78 km2) in Roslyn. These houses can be classified as three types, depending on their locations: Gold Coast chateaux along the wealthiest tier, mostly in Nassau County; neo-Colonial structures, especially those in the neighborhood of his own house at "Box Hill" in Smithtown, Suffolk County; and the South Fork houses in Suffolk County, from Southampton to Montauk Point, influenced by their coastal location. He also designed the Kate Annette Wetherill Estate in 1895.

White designed a number of other New York mansions as well, including the Iselin family estate "All View" and "Four Chimneys" in New Rochelle, suburban Westchester County. White designed several country estate homes in Greenwich, Connecticut, including the Seaman-Brush House (1900), now the Stanton House Inn, operated as a bed and breakfast.[14] In New York's Hudson Valley, he designed the 1896 Mills Mansion in Staatsburg.

Among his "cottages" in Newport, Rhode Island, at Rosecliff (1898–1902, designed for Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs) he adapted Mansart's Grand Trianon. The mansion was built for large receptions, dinners, and dances with spatial planning and well-contrived dramatic internal views en filade. His "informal" shingled cottages usually featured double corridors for separate circulation, so that a guest never bumped into a laundress with a basket of bed linens. Bedrooms were characteristically separated from hallways by a dressing-room foyer lined with closets, so that an inner door and an outer door gave superb privacy.

One of the few surviving urban residences designed by White is the Ross R. Winans Mansion in Baltimore's Mount Vernon-Belvedere neighborhood. It is now used as the headquarters for Agora, Inc. Built in 1882 for Ross R. Winans, heir to Ross Winans, the mansion is a premier example of French Renaissance revival architecture. Since its period as Winans's residence, it has served as a girls preparatory school, doctor's offices, and a funeral parlor, before being acquired by Agora Publishing. In 2005, Agora completed an award-winning renovation project.[15]

White designed Golden Crest Estate in Elberon Park, NJ while at McKim Mead and White for E. F. C. Young, President of the First National Bank of Jersey City and unsuccessful Democratic candidate for New Jersey Governor in 1892. He built the house in 1901, as a golden wedding anniversary gift for Young's wife Harriet. In 1929, the house was sold to Victor and Edmund Wisner, who ran it as a rooming house for summer vacationers. In the 1960s, it was a fraternity house for the then Monmouth College. From 1972 to 1976, it was owned and restored by Mary and Samuel Weir. It is now a private residence.

White lived the same life as his clients, albeit not quite so lavishly, and he knew how the house had to perform: like a first-rate hotel, theater foyer, or a theater set with appropriate historical references. He could design a cover for Scribner's Magazine or design a pedestal for his friend Augustus Saint-Gaudens's sculpture.

He extended the limits of architectural services to include interior decoration, dealing in art and antiques, and planning and designing parties. He collected paintings, pottery, and tapestries for use in his projects. If White could not acquire the right antiques for his interiors, he would sketch neo-Georgian standing electroliers or a Renaissance library table. His design for elaborate picture framing, the Stanford White frame, still bears his name today. Outgoing and social, he had a large circle of friends and acquaintances, many of whom became clients. White had a major influence in the Shingle Style of the 1880s, Neo-Colonial style, and the Newport cottages for which he is celebrated.

He designed and decorated Fifth Avenue mansions for the Astors, the Vanderbilts (in 1905), and other high society families.

White in 1895

White, a tall, flamboyant[4] man with red hair and a red mustache, impressed some as witty, kind, and generous. The newspapers frequently described him as "masterful", "intense", "burly yet boyish".[16] He was a collector of rare and costly artwork and antiquities. He maintained a multi-story apartment with a rear entrance on 24th Street in Manhattan. One room was painted green and outfitted with a red velvet swing, which hung from the ceiling suspended by ivy-twined ropes. It has been suggested,without any substantiated proof, that he may have used playing with the elaborate swing as a means to attract women, including Evelyn Nesbit, a popular photographer's fashion model and chorus dancer.[17][18]

After White was killed and the newspapers began to investigate his life, continuing through the trial of Thaw, it was suggested that the married architect engaged in sexual relations with numerous women. The White family historian Suzannah Lessard writes:

The process of seduction was a major feature of Stanford's obsession with sex, and it was an inexorable kind of seduction which moved into the lives of very young women, sometimes barely pubescent girls, in fragile social and financial situations—girls who would be unlikely to resist his power and his money and his considerable charm, who would feel that they had little choice but to let him take over their lives. There are indications that Stanford would sometimes adopt the role of a paternal benefactor, and then would take advantage of the trust and gratitude that had been built.[19]

White has been accused of belonging to an underground sex circle, made up of select members from the Union Club, a legitimate men's club. According to Simon Baatz:

He was one of a group of wealthy roués, all members of the Union Club, who organized frequent orgies in secret locations scattered about the city. Other members of the group included Henry Poor, a financier; James Lawrence Breese, a wealthy man-about-town with an avocational interest in photography; Charles MacDonald, a stockbroker and principal shareholder in the Southern Pacific Railroad; and Thomas Clarke, a dealer in antiques.[20]

Mark Twain, who was acquainted with White, included an evaluation of his character in his Autobiography. It reflected Twain's deep immersion in the testimony of the Thaw murder trial. Twain said that New York society had known for years preceding the incident that the married White was

eagerly and diligently and ravenously and remorselessly hunting young girls to their destruction. These facts have been well known in New York for many years, but they have never been openly proclaimed until now. On the witness-stand, in the hearing of a court room crowded with men, the girl [Evelyn Nesbit] told in the minutest detail the history of White's pursuit of her, even down to the particulars of his atrocious victory—a victory whose particulars might well be said to be unprintable...[21]

Based on White's correspondence, including that conducted with Augustus Saint-Gaudens, recent biographers have concluded that White was bisexual, and that the office of McKim, Mead & White was unruffled by this.[22] White's granddaughter has written that Stanford's eldest son (her father) was "unflinching in his awareness of Stanford's nature".[23]

Relationship with Evelyn Nesbit, death and aftermath

[edit]

In 1901, White established a caretaking relationship with Evelyn Nesbit, helping Nesbit get established as a model for artists and photographers in New York society, with the approval of Nesbit's mother. Five years later, Nesbit would testify that one evening he invited her to his apartment for dinner and gave her champagne and possibly some drug, and then raped her after she passed out: she was about 16 years old at this time and White was 48.[24]

For a period of at least six months after the alleged rape,[_clarification needed_] they acted as lovers and companions. Although they drifted apart, they remained in touch with each other and on good terms socially.

In 1905, she married Harry Kendall Thaw, a Pittsburgh millionaire with a history of severe mental instability. Thaw was jealous of White's acceptance in society and thought of White as his rival. But, well before he was killed, White had moved on to other young women as lovers.[25] White considered Thaw a poseur of little consequence and categorized him as a clown, once calling him the "Pennsylvania pug" – a reference to Thaw's baby-faced features.[26]

Accompanied by New York society figure James Clinch Smith,[27] White dined at Martin's, near Madison Square Garden. As it happened, Thaw and Nesbit also dined there, and Thaw was said to have seen White at the restaurant.[25]

That evening the premiere of Mam'zelle Champagne was being performed at the theatre. During the show's finale, "I Could Love A Million Girls", Thaw approached White, produced a pistol, said, "You've ruined my wife",[25] and fired three shots at White from two feet away. He hit White twice in the face and once in his upper left shoulder, killing him instantly.[3][28] The crowd's initial reaction was to think the incident was an elaborate party trick. When it became apparent that White was dead, chaos ensued.

Nineteen-year-old Lawrence Grant White was guilt-ridden after his father was slain, blaming himself for the death. "If only he had gone [to Philadelphia]!" he lamented, referring to a trip that had been planned.[29] Years later, he would write, "On the night of June 25th, 1906, while attending a performance at Madison Square Garden, Stanford White was shot from behind [by] a crazed profligate whose great wealth was used to besmirch his victim's memory during the series of notorious trials that ensued."[_citation needed_] (In fact, White was shot in the face, from directly in front of him, not from behind.)

White was buried in St. James, New York, in Suffolk County.[30]

The New York American on June 26, 1906

Aftermath and news coverage

[edit]

Following the killing, there was blanket press coverage, as well as editorial speculation and gossip. Journalistic interest in the sensational story was sustained. William Randolph Hearst's newspapers played up the story, and the subsequent murder trial became known as "The Trial of the Century".[31]

White's reputation was severely damaged by the testimony in the trial, as his sexual activities became public knowledge. The Evening Standard spoke of his "social dissolution". A headline in Vanity Fair read "Stanford White, Voluptuary and Pervert, Dies the Death of a Dog".[32] The Nation reconsidered his architectural work: "He adorned many an American mansion with irrelevant plunder." Newspaper accounts drew from the trial transcripts to describe White as "a sybarite of debauchery, a man who abandoned lofty enterprises for vicious revels".[33]

Ultimately, Thaw was tried for murder twice for the shooting of White. The first trial ended with a mistrial due to a hung jury, and the jury in the second trial found him not guilty by reason of insanity.

Few friends or associates publicly defended White, as some feared possible exposure for having participated in White's secret life. McKim responded to inquiries saying, "There is no statement to make...There will be no information coming from us."[34]

Richard Harding Davis, a war correspondent and reputedly the model for the "Gibson Man", was angered by the press accounts, which he said presented a distorted view of his friend White. An editorial published in Vanity Fair, lambasting White, prompted Davis to a rebuttal. His article appeared on August 8, 1906, in Collier's magazine:

Since his death White has been described as a satyr. To answer this by saying that he was a great architect is not to answer at all...He admired a beautiful woman as he admired every other beautiful thing God has given us; and his delight over one was as keen, as boyish, as grateful over any others.[35]

The autopsy report, made public by the coroner's testimony at the Thaw trial, revealed that White was in poor health when killed. He suffered from Bright's disease, incipient tuberculosis, and severe liver deterioration.[36]

- In The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing, a 1955 movie, Ray Milland played White.[37]

- The 1975 historical fiction novel Ragtime by E. L. Doctorow

- The 1981 film Ragtime, adapted from the novel of the same name. White was played by writer Norman Mailer, Thaw by Robert Joy, and Nesbit by Elizabeth McGovern.[38]

- The 1996 musical Ragtime, based on the novel[39]

- Dementia Americana – a long narrative poem by Keith Maillard (1994, ISBN 9780921870289)

- My Sweetheart's the Man in the Moon – a play by Don Nigro (ISBN 9780573642388)[40]

- La fille coupée en deux ("The Girl Cut in Two") – a 2007 film by Claude Chabrol was inspired, in part, by the Stanford White scandal.[41]

- In the 2022 HBO series The Gilded Age, White is a recurring character who fictionally designed the nouveau riche Russell family's Upper East Side mansion. He is played by John Sanders.[42]

Gallery of architectural works

[edit]

Madison Square Garden (1890), New York City

Washington Square Arch (1891–1895), New York City

Cocke Hall (1896) at the University of Virginia

Payne Whitney House (1902–1906), New York City

White's extensive professional correspondence and a small body of personal correspondence, photographs, and architectural drawings by White are held by the Department of Drawings & Archives of Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. His letters to his family have been edited by Claire Nicolas White, Stanford White: Letters to His Family 1997. The major archive for his firm, McKim, Mead & White, is held by the New-York Historical Society.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (August 23, 2018). "There's Plenty to Read About the 'Trial of the Century'". The New York Times.

- ^ Blecher, George (August 3, 2018). "Murder, Politics and Architecture: The Making of Madison Square Park". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Benjamin Thaw Too Ill to be Told of His Brother's Crime". New York Times. June 26, 1906. Retrieved October 9, 2010. Social and financial circles in Pittsburg were greatly shocked to-night by the news from New York that Harry K. Thaw had shot and killed Stanford White. The Thaws have for years been social leaders here. Harry Kendall Thaw, the husband of Florence Evelyn Nesbit, over whom Thaw and White are said to have quarreled, has for some years been the black sheep of the Thaw family.

- ^ a b c d e Lockhart, Mary. Treasures of New York: Stanford White (TV, 2014) WLIW. Broadcast accessed:2014-01-05

- ^ Harrison, Helen A. (November 28, 2004). "Creative Lines, Haunted by Scandal". The New York Times.

- ^ "Madison Square Garden" on the New York Architecture website

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "Streetscapes: The 1893 Cable Building, Broadway and Houston Street; Built for New Technology by McKim, Mead & White" New York Times (November 7, 1999)

- ^ "Photos and videos by Paulist Fathers (@PaulistFathers)". Pinterest. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "Church of St. Paul the Apostle, NYC". Pinterest. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "Church of St. Paul the Apostle, NYC". Pinterest. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Stoelker, Tom (October 6, 2011) "Murder, Love, and Insanity: Stanford White" The Architect's Newspaper

- ^ "photograph". Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ Roth, L. M. The Architecture of McKim, Mead & White, 1870–1920: a building list, 1978, provides a working list of commissions.

- ^ "Seaman Brush House, 76 Maple Avenue, 1936", Greenwich Historical Society website

- ^ "Baltimore Heritage – Ross Winans Mansion". January 10, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Uruburu, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Baatz, Simon. The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Little, Brown, 2018) ISBN 978-0316396653: Chapter 1

- ^ Dworin, Caroline H. (November 4, 2007). "The Girl, the Swing and a Row House in Ruins". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ Lessard, Suzannah. (1996) The Architect of Desire: Beauty and Danger in the Stanford White Family. New York: Dell: Chapter 12 [Danger]. ISBN 0385319428

- ^ Baatz, Simon. The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Little, Brown, 2018) ISBN 978-0316396653: Chapter 3

- ^ Twain, Mark. (2013) Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume Two, Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 454.

- ^ Broderick, Mosette. (2010) Triumvirate: McKim, Mead & White Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America's Gilded Age. New York: Knopf, pp. vii–viii, 41. ISBN 9780394536620

- ^ Lessard, Suzannah. (1996) The Architect of Desire: Beauty and Danger in the Stanford White Family. New York: Dell p. 204. ISBN 0385319428

- ^ "Stanford White & Evelyn Nesbit", People (February 12, 1996)

- ^ a b c Nevius, Michelle & Nevius, James (2009), Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, New York: Free Press, ISBN 141658997X, pp. 195–197

- ^ Uruburu, p. 181

- ^ Lord, Walter. "Chapter 2". A Night to Remember. p. 5.

- ^ Uruburu, pp. 279, 282

- ^ Uruburu, p. 279

- ^ Kuehn, Henry H. (2017). Architects' Gravesites: A Serendipitous Guide. MIT Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-262-34074-8.

- ^ Uruburu, p. 319

- ^ Bird, Christiane (2002). A Block in Time. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 231.

- ^ Uruburu, p. 307

- ^ Baatz, Simon. The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Little, Brown, 2018) ISBN 978-0316396653: Chapter 4

- ^ Uruburu, pp. 306–307

- ^ Uruburu, p. 330

- ^ The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing at the TCM Movie Database

- ^ Ragtime at AllMovie

- ^ "Ragtime". IBDB.com. Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ "My Sweetheart's the Man in the Moon". Samuel French, Inc. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Jenkins, Mark (August 14, 2008) "'Girl Cut in Two': An Old Scandal, Stylishly Redressed", NPR

- ^ Bilyeau, Nancy (February 1, 2022). "What The Gilded Age Gets Right About Infamous Architect Stanford White". Town & Country. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- Baker, Paul R., Stanny: The Gilded Life of Stanford White, The Free Press, NY 1989.

- Baatz, Simon, The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century, New York: Little, Brown, 2018. ISBN 978-0316396653

- Collins, Frederick L., Glamorous Sinners, Ray Long & Richard R. Smith, 1932.

- Craven, Wayne. Stanford White: Decorator in Opulence and Dealer in Antiquities, Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Langford, Gerald, The Murder of Stanford White, Victor Gollancz, 1963.

- Lessard, Suzannah, The Architect of Desire: Beauty and Danger in the Stanford White Family, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1997. (written by White's great-granddaughter, a Whiting Award-winning writer for The New Yorker)

- Mooney, Michael, Evelyn Nesbit and Stanford White: Love and Death in the Gilded Age, New York, Morrow, 1976.

- Roth, Leland M., McKim, Mead & White, Architects, Harper & Row, Publishers, NY 1983.

- Samuels, Charles, The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing, Gold Medal Books, 1953.

- Nesbit, Evelyn, The Story of My Life, John Long, 1914.

- Nesbit, Evelyn, Prodigal Days. The Untold Story, Julian Messner, 1934.

- Thaw, Harry K., The Traitor, Dorrance & Co., 1926.

- Uruburu, Paula, American Eve: Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White, The Birth of the "It" Girl and the Crime of the Century, Riverhead, 2008.

- White, Samuel G. with Jonathan Wallen (photographer). The Houses of McKim, Mead and White, Rizzoli, 1998.

- Stanford White Papers,1873–1928 New-York Historical Society

- "Stanford White on Long Island" a museum essay on White's residential projects

- New York Architecture Images – New York Architects – McKim, Mead, and White Firm history with images

- Stanford White at Find a Grave

- Gilding the Gilded Age: Interior Decoration Tastes & Trends in New York City A collaboration between The Frick Collection and The William Randolph Hearst Archive at LIU Post.

- "Works of Art from the Collection of Stanford White", The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives. Digital images of a scrapbook compiled by Lawrence Grant White, son of Stanford White, on works of art collected by Stanford White, including paintings, sculpture, rugs, tapestries, and other decorative arts.

- "Catalogue of Works of Art at 'Box Hill', St. James, Long Island", The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives. Pdf scan of inventory of works of art at Box Hill, the former Stanford White estate in Long Island, completed in 1942.

- The McKim Mead & White Architectural Records Collection at the New York Historical Society

- Stanford White correspondence and architectural drawings, 1887–1922, (bulk 1887–1907), held by the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University