T. B. Walker (original) (raw)

American business magnate

| T. B. Walker | |

|---|---|

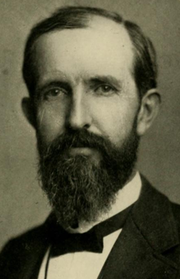

Thomas Barlow Walker in 1888 Thomas Barlow Walker in 1888 |

|

| Born | Thomas Barlow WalkerFebruary 1, 1840Xenia, Ohio, United States |

| Died | July 28, 1928(1928-07-28) (aged 88)Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States |

| Occupation(s) | businessperson, art collector |

| Known for | lumber, Minneapolis Public Library, Walker Art Center |

| Spouse | Harriet G. Walker |

| Children | Gilbert, Julia, Leon, Harriet, Fletcher, Willis, Clinton, and Archie |

| Relatives | Andrew Bonney Robbins (brother-in-law)Amy Robbins Ware (niece) |

| Signature | |

|

Thomas Barlow Walker (February 1, 1840 – July 28, 1928) was an American business magnate who acquired lumber in Minnesota and California and became an art collector. Walker founded the Minneapolis Public Library. He was among the ten wealthiest men in the world in 1923.[1] He built two company towns, one of which his son sold to become part of what is today known as Sunkist. He is the founder and namesake of the Walker Art Center.

Early life and family

[edit]

T.B. Walker, c. 1860.

T. B. Walker was the son of Platt Walker and Anstis Keziah (Barlow) Walker (1814–1883), a sister of New York State Senator Thomas Barlow (1805–1896).[2] He was born in Xenia, Ohio, in 1840, where in 1849 he got his first job in a bakery cutting biscuits.[1] He had accompanied his parents and siblings west from New York when his father died of cholera in 1849 at Westport, Missouri, on their way to the California gold fields to seek their fortune.[3][4]

Harriet G. Walker, wife, mother of eight children and president of Northwestern Hospital

In 1854, his mother married Oliver Barnes and in 1855 his family moved to Berea, Ohio, where while traveling for Fletcher Hulet,[5] he was able to study mathematics intermittently and Newton's Principia[5][6] at Baldwin University. When he finished college at age 19, he filled a contract in Paris, Illinois for railroad ties. He then taught school and then became a traveling salesman of grindstones.[2] He is remembered as a man of "strong opinions" who would not eat grapefruit and who slept with a pistol under his pillow.[1] His brother Platt Bayless Walker II founded Mississippi Valley Lumberman, a magazine.[3] He had another brother and two sisters: Oliver W. Barnes, Adelaide B. Walker, and Helen M. Walker.[3]

Walker married his college classmate and boss's daughter Harriet Granger Hulet in 1863.[4] They had eight children and lived in Minneapolis[4] at first in a home on the east side rented for $9 per month.[7] Their children were Gilbert M. (1864–1928), Julia A. (1865?–1952?), Leon B. (1868–1887), Harriet (1870–1904), Fletcher L. (1872–1962), Willis J. (1873–1943), Clinton L. (1875–1944), and Archie D. (1882–1971).[3] The Walkers celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 1913.[8] One of Walker's grandsons was Olympic hurdler Walker Smith.[9]

From a man in Iowa,[5] Walker heard good things about Minneapolis, Minnesota, and moved there in 1862.[4] He arrived at Saint Paul where he met and sold grindstones, once to James Jerome Hill, then employed as a clerk who carefully sorted them for the buyer.[5] Within one hour of his arrival in Minneapolis, he was hired as a chainman[3] to George B. Wright, who was surveying federal pine lands in the north of the state.[4] He became a deputy surveyor within a few days.[5] His application to become assistant professor in mathematics at the University of Wisconsin had been accepted but he loved his new career and turned it down.[5] Walker worked for twelve years on government surveys and on surveys for the St. Paul and Duluth Railroad.[2] His work took him away from home for long periods,[4] and it gave him intricate knowledge of what property to buy in northern Minnesota.[3] He began to acquire pine land in 1867, but without capital of his own, he partnered at first with Dr. Levi Butler and Howard W. Mills and later with others.[5]

With George A. Camp, in 1877 Walker bought the Pacific Mill,[3] a sawmill constructed in 1866 at the foot of 1st Avenue North on the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, which they owned for ten years before dissolving their partnership amicably.[10]

Red River Lumber Company (RRLC) was founded in 1883 and incorporated the following year.[3] His oldest sons Gilbert and Leon[11] became partners with Walker[12] and the company built more mills in Crookston, Minnesota and at Grand Forks, Dakota Territory.[3] He developed the town and built a mill at Akeley, Minnesota, which was named for his business partner, Healy C. Akeley.[3] By 1902, four of his sons were involved in his businesses, and one was still in school.[13]

He was concerned about forest conservation and wrote an article for the National Magazine about what had become the "forestry question". During his lifetime, he gave papers to the Conservation Commission, the U.S. Forestry Department, the U.S. Interior Department and to the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee for their consideration for a tariff on lumber. He gave a presentation on conservation to the Minnesota Academy of Science.[2]

He had to spend months up north, but finally returned to Minneapolis in 1881 intending to build up the city.[4] Walker said, "St. Paul had the wholesale trade, the retail trade, the railroads and the banks. We tried five years to arrange an amicable interest in building up the industries of both cities."[4] He and others tried to lure a factory from the east but was double-crossed when Saint Paul, at the time a rival, ended up with both the eastern and the Minneapolis factories.[4] He and his friends also invested in the Midway area but the city of Saint Paul annexed it.[4]

Walker built the commercial market in Minneapolis, renowned at the time, into the best produce market in the U.S.[2] He is also "primarily responsible" for building the Minneapolis Public Library system, first with donations and as a stockholder[5] in the Athenaeum Library Association and later with public property tax.[2] He eventually overcame opposition to the idea of a free public library.[14] Walker was a director and president of the library board from its founding in 1885 until he died in 1928.[3]

Four-fifths[2] of the art displayed at the library came from his own collection which he had started to collect in 1874 when he purchased a copy of a portrait of George Washington by Rembrandt Peale for the library of his new home.[3][15] He was particularly interested in creating a public art gallery, a museum, and the Minneapolis Art School.[2]

He became president of the Business or Businessman's Union, which formed in 1883 for fifteen years.[4] They chose to build up land west of Minneapolis for their industrial site, to avoid any possibility of Saint Paul annexing the land.[4] According to Walker, "some of the men in the union who liked changes made a social club of it, in the Guaranty Loan Building [known as the Metropolitan Building, since demolished]. This practically closed out the Business Union."[4]

Walker home at 803 Hennepin Avenue, Minneapolis

Walker built his first house in Minneapolis in 1870, at Ninth Street and Marquette Avenue.[3] In 1874 he built a mansion at 803 Hennepin Avenue.[3] A gallery was open to the public six days a week beginning in 1879 to display his paintings, porcelain, bronzes, jades, ancient and modern high-grade glass, carved crystals, ancient Chinese carved snuff-boxes and ivory carvings.[2] Visitors had to ring at the front door until the home was expanded.[15] The house and its eight additions covered nearly a city block[1] but were later demolished to build a complex that includes the State Theatre.[3]

His paintings included 15 American landscapes,[16] 103 portraits of Native American chiefs, medicine men and warriors, and 24 portraits of renowned cowboys, scouts and guides,[17] alongside traditional works by Raphael, Rembrandt, Holbein, Ingres, Titian, Bonheur, Turner and Michelangelo and dozens of other artists.[18] Some of these paintings proved to be fakes and some were genuine—certainly, a landscape by Frederic Edwin Church sold for $8.5 million in a 1989 Sotheby's New York auction.[6]

Walker Art Center in 1941, opened in 1927

In 1915 Walker purchased the 3.5-acre (0.014 km2) Thomas Lowry property[1] on Groveland Terrace including the present Walker Art Center. In 1917 Walker moved into the Lowry Mansion but it was demolished in about 1932.[3] By 1915 the Walker Galleries on 803 Hennepin had 14 rooms, and had about 100,000 visitors each year.[3] In 1926, Walker completed building a new gallery next door to the Lowry Mansion on the site of the present Walker Art Center which opened in 1927. Built by local architects, Long and Thorsov, the original Walker Art Center building stayed open until it was demolished in 1969 to make way for a new building by Edward Larrabee Barnes.[3]

The T. B. Walker Collection (1907)[18]

Speaking of the 25 to 30 people who founded the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, Donald Torbert wrote:

"Today it is impossible to assess, with anything approaching justice, the worth of the individual contributions, because each person was indispensable. But two, by reason of their energy and position in the community, played leading roles and through their accomplishments left a permanent imprint on the art life of the community. They were William Watts Folwell and Thomas Barlow Walker."[19]

During the early 20th century, Walker published catalogs of his art collection[18] which he wanted to give to the city of Minneapolis.[3] He presented the deeds to his collection and 3.5 acres (0.014 km2) of land to the library board in 1918.[17] According to the Minnesota Historical Society, the city refused the gift.[3]

Today, the Art Gallery at Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church has several paintings from Walker's collection.

Walker wanted to build a large public library and an arts and sciences institution but the city failed to provide financial support[20]—the Minnesota legislature authorized bonds for $500,000 but only half of them sold.[1] For five years,[21] the city negotiated with Walker but never reached mutual satisfaction, and in 1923 he rescinded the offer.[1] Folwell wrote in his A History of Minnesota, "Walker wisely followed his independent course".[15] Walker Galleries, Inc., was incorporated in 1924, and the T. B. Walker Foundation of today was founded in 1925 to "own and manage the collection and gallery".[3]

Most of his collection was given away or sold to buy modern works.[22] A gallery across the street at Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church holds several of the works in his collection by 16th- and 19th-century European masters, which Walker donated to decorate the Sunday school.[6]

St. Louis Park, Minnesota

[edit]

In 1886, with Calvin Goodrich, Jr. and Henry Francis Brown, Walker founded the Minneapolis Land and Investment Company and became its president.[4] By 1888, the company advertised 12,000 lots on their 1,700 acres (6.9 km2), just west of the city limits near Bde Maka Ska, with the industry "in the marsh". Residential lots were 22 feet (6.7 m) wide, so that developers could build a garden in every other lot. The Industrial Circle exists today at Dakota and Walker Streets in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, near the intersection of Highway 7 and Louisiana. Daniel J. Falvey, the village roadmaster, graded the roads. Walker built about 100 Walker Houses between 1888 and 1900 for his workers to rent at 9to9 to 9to14 per month.[23] Around this time, Walker was the richest man in Minnesota.[7] About 50 of the houses remained in 1999 in the Edgebrook neighborhood.[23]

The Panic of 1893 left Walker owning and paying taxes on many unsold lots[23] and his partners departed, assigning their land to Walker. In 1913 he owned about 600 or 700 of 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) but the land was worth less than he had paid for it. Walker then turned his attention to the Pacific coast. He used money made there to pay off his unsold lots in Minnesota.[4] His dream of a large downtown St. Louis Park disappeared in twelve years, but to that end he had built a Methodist church (which later burned),[24] the Walker/Syndicate[25] building (still standing),[26] the St. Louis Park Hotel (which the village later demolished),[27] The Great Northern Hotel (which later burned down)[27] and a streetcar line to Minneapolis.[4] According to the St. Louis Park Historical Society, Walker could be seen "giving out food during the Depression, but people shied away from him and even despised him".[4] The E.H. Shursen Agency sold the last lot during the 1930s.[23]

T. B. Walker died at his home in Minneapolis in 1928. He was buried at Lakewood Cemetery, Minneapolis.[3]

His wife died in 1917 while accompanying Walker on a business trip to New York.[4] They were both buried in Lakewood.[3] Walker was among the 15 or so wealthiest persons in the world when he died.[6]

A portrait of T. B. Walker in 1915 by Carl Boeckman, acquired at some time since 1940, was on display at the Walker Art Center from November 21, 2009 until August 15, 2010.[28] In the Walker's recent collection, Walker appears in Lost Forty (2011), a huge tapestry by Goshka Macuga picturing a tract of unlogged land in the Chippewa National Forest.[29]

Westwood, California

[edit]

Left to right: Fletcher, Willis, Archie, T.B., Gilbert and Clinton Walker in 1907. He also had daughters, Julia, and Harriet who died in 1904. Leon, another son, died in 1887.

Walker started to acquire northerneastern California land in 1894. In 1909 he bought property near Mountain Meadows, California. In 1912 RRLC signed an agreement with the Southern Pacific Railroad giving them the right to build a line (the Fernley and Lassen Railway) and exclusive right to haul lumber.[4] RRLC may have owned 900,000 acres (3,642 km2) of timberland in California,[3] or about 1% of the area of the state, by the time Walker retired c. 1912.

About 1912[3] RRLC built a mill and the company town of Westwood, California.[4] Westwood included houses, apartments, dormitories, hotels, a community center, a department store, churches, and a theater.[4] All utilities were company-owned.[4] The men had the "Westwood Club" to themselves but for the first 20 years no liquor was sold.[4]

About this time, Walker retired from RRLC which his sons Gilbert, Fletcher, Willis, and Archie then ran. Walker grew "increasingly frustrated" that he could not control the business by himself.[3] The Minnesota Historical Society notes that his sons did not always see "eye to eye" with each other or with Walker.[3]

Walker's youngest son Archie Dean Walker was first secretary (1908–1933) and then president (1933–c. 1956) of RRLC.[4] Archie was Minneapolis-based and during his tenure on November 30, 1944, the Westwood mill and town were sold to the Fruit Growers Supply Company, the buying arm of today's Sunkist.[4]

List of associations and affiliated businesses

[edit]

Walker's many business ventures and associations included the Crookston Boom and Water Power Company, the International Lumber Company in Minneapolis, the Metropolitan Trust Company in Minneapolis, the Minneapolis Central City Market Company, the Minneapolis Esterly Harvester Company, the Minnesota and Dakota Elevator Company in Minneapolis, the National Lumber Convention in Washington, D.C., the Northern Minnesota Log Driving & Boom Company, the Northwestern Elevator Company in Minneapolis, Pacific Investment Company, and the Waland Lumber Company. Walker was president of the Flour City National Bank in Minneapolis from 1887 to 1894. He was one of the incorporators of Edison Light & Power Co.[30] He was one of the managers of the State Reform School in Saint Paul.[5] He was involved in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915.[3]

Walker was a trustee of the Hennepin Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church (now known as the Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church in Minneapolis), a member of the Executive Committee of the Methodist Episcopal General Conference in Minneapolis, and a president of the Minneapolis Methodist Church Extension Society. He was a member of the executive committee of the See America League, a president of Walker Galleries, Inc., a president and a trustee of the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, president of the Minnesota Academy of Natural Sciences and its successor, the Minnesota Academy of Science where he donated boxes of specimens,[2] and a trustee of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) of the City of Minneapolis.[3]

- Butler, Mills & Walker, later L. Butler & Company, reestablished as Butler & Walker, lumber 1869–1872

- Camp & Walker 1877–1887, Pacific Mill 1877–1887

- Walker & Akeley 1887

- Red River Lumber Company (RRLC) 1883–1897, California 1912–1944

- Akeley, Minnesota (developed town), also mill 1899–1915

- Westwood, California (company town) approx. 1912–1913 to retirement

- Walker, Minnesota was named for him[1]

- Harriet G. Walker

- Walker Art Center

- ^ a b c d e f g h Madison, Cathy (2005). Walker Art Center. Scala. pp. 5–13. ISBN 1-85759-377-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wilson, James Grant and Fiske, John (original ed.). The Cyclopaedia of American biography. Vol. 8. New York Press Association Compilers, via Internet Archive. pp. 115–116. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

{{[cite book](/wiki/Template:Cite%5Fbook "Template:Cite book")}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Peterson, David B. (processor). "Biographies of the Walker Family in T. B. Walker and Family Papers". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved November 2, 2007. [_dead link_]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "T. B. Walker". St. Louis Park Historical Society. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Atwater, Isaac (1893). History of the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Vol. 2. Munsell. pp. 562–565.

- ^ a b c d Abbe, Mary (April 9, 2005). "Art lover T.B. Walker: Where it all began". Star Tribune. Avista Capital Partners. Archived from the original on July 26, 2007. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- ^ a b "A Minnesota Millionaire". Chicago Inter-Ocean, via Internet Archive. p. 59. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Walker, Thomas Barlow (1913). Announcing the fiftieth anniversary of the marriage of Thomas Barlow Walker. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ Hodak, George A. (1988). "An Olympian's oral history: Walker Smith, 1920 Olympic Games, Track & Field" (PDF). LA84 Foundation Digital Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2016.

- ^ Anfinson, Scott F. (1990). "Archaeology of the Central Minneapolis Riverfront: Part 2: Archaeological Explorations and Interpretive Potentials - Figure 32". The Minnesota Archaeological Society. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ Walker, Platt B. Sketches of the life of Honorable T. B. Walker. Lumberman Publishing Company via Internet Archive. p. n27. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- ^ Isaac Atwater (1893). History of the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Munsell. p. 571.

- ^ O'Brien, D. E. (January 1902). "Thomas Barlow Walker". Vol. V, no. 1. Successful American, via Internet Archive. p. 57. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Atwater, Isaac (1893). History of the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Vol. 1. pp. 282–299.

- ^ a b c Folwell, William Watts, 1921 to 1930 (2006). A History of Minnesota. Vol. 4. Minnesota Historical Society Press. pp. 465–472. ISBN 0-87351-490-4.

{{[cite book](/wiki/Template:Cite%5Fbook "Template:Cite book")}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Abbe, Mary (September 11, 2007). "Walker Art Center hires 'rising star' to take helm". Star Tribune. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Shutter, Marion Daniel, ed. (1932). History of Minneapolis: Gateway to the Northwest. p. 13. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ a b c Walker, Thomas Barlow (1907). Catalog of the Art Collection of T. B. Walker. Minneapolis: via Internet Archive scan of University of Michigan copy. Retrieved November 3, 2007.

- ^ Torbert, Donald (1958). A Century of Art and Architecture in Minnesota. University of Minnesota Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-8166-0175-5.

- ^ Walker Art Center (1985). Walker Art Center: A History. Walker Art Center. p. 3.

- ^ Rothfuss, Joan; Carpenter, Elizabeth, eds. (2005). Bits & Pieces Put Together to Present a Semblance of a Whole: Walker Art Center Collections. Walker Art Center. p. 13. ISBN 0-935640-78-9.

- ^ Abbe, Mary (November 19, 2009). "Art: Walker to the max". Star Tribune. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Walker Houses". St. Louis Park Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "T.B. Walker's Methodist Church". St. Louis Park Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "Walker Building". St. Louis Park Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "The Brick Block". St. Louis Park Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 25, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ a b "Early Park Hotels". St. Louis Park Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "Benches & Binoculars". Walker Art Center. Archived from the original on March 6, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ Fong, Kristina (May 18, 2011). "#IMD2011: Museum, Memory, and "Goshka Macuga: It Broke From Within"". Walker Art Center.

- ^ Isaac Atwater (1893). History of the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Munsell. p. 666.

- Huber, Molly (June 6, 2011). "Walker, Thomas Barlow (T. B.), (1840–1928)". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- Whitmore, Janet (Autumn 2004). "Presentation Strategies in the American Gilded Age: One Case Study". Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art (AHNCA). Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- Works by or about T. B. Walker at the Internet Archive

- Biographical Sketch with portrait photo

- Walker, Platt B., ed. (1907). Sketches of the Life of Honorable T. B. Walker. Lumberman Publishing Company.

- Encyclopedia of Baldwin Wallace University History: TB Walker