The Lathe of Heaven (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1971 novel by Ursula K. Le Guin

The Lathe of Heaven

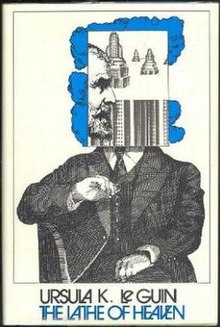

Cover of first edition (hardcover) Cover of first edition (hardcover) |

|

|---|---|

| Author | Ursula K. Le Guin |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Avon Books |

| Publication date | 1971 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 184 |

| Awards | Locus Award for Best Novel (1972) |

| ISBN | 0-684-12529-3 |

| OCLC | 200189 |

The Lathe of Heaven is a 1971 science fiction novel by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin, first serialized in the American science fiction magazine Amazing Stories. It received nominations for the 1972 Hugo[1] and the 1971 Nebula Award,[2] and won the Locus Award for Best Novel in 1972.[1] Two television film adaptations were released: the PBS production, The Lathe of Heaven (1980), and Lathe of Heaven (2002), a remake produced by the A&E Network.

The novel explores themes and philosophies such as positivism, Taoism, behaviorism, and utilitarianism. Its central plot surrounds a man whose dreams are able to alter past and present reality and the ramifications of those psychologically derived changes for better and worse.

The title is from the writings of Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zhou) — specifically a passage from Book XXIII, paragraph 7, quoted as an epigraph to Chapter 3 of the novel:

To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven. (知止乎其所不能知,至矣。若有不即是者,天鈞敗之。)

Other epigraphs from Chuang Tzu appear throughout the novel. Le Guin chose the title because she loved the quotation. However, it seems that quote is a mis-translation of Chuang Tzu's Chinese text.

In Nothingness, Being, and Dao: Ontology and Cosmology in the Zhuangzi, Chai describes the concept of 天鈞 as 'heavenly equilibrium'.[3]

In an interview with Bill Moyers for the 2000 DVD release of the 1980 adaptation, Le Guin clarified the issue:

...it's a terrible mis-translation apparently, I didn't know that at the time. There were no lathes in China at the time that was said. Joseph Needham wrote me and said "It's a lovely translation, but it's wrong".[4]

She published her rendition of the Tao Te Ching, The Book of the Way and Its Virtue by Lao Tzu, the traditional founder of Taoism (Daoism). In the notes at the end of this book, she explains this choice:

The language of some [versions of the _Tao Te Ching_] was so obscure as to make me feel the book must be beyond Western comprehension. (James Legge's version was one of these, although I found the title for a book of mine, The Lathe of Heaven, in Legge. Years later, Joseph Needham, the great scholar of Chinese science and technology, wrote to tell me in the kindest, most unreproachful fashion Legge was a bit off on that one; when Chuang Tzu was written the lathe hadn't been invented.) [5]

Translated editions titled the novel differently. The German and first Portuguese edition titles, Die Geißel des Himmels and O flagelo dos céus, mean literally "the scourge [or whip] of heaven". The French, Swedish and second Portuguese edition titles, L'autre côté du rêve, På andra sidan drömmen and Do outro lado do sonho, translate as "the other side of the dream".

The book is set in Portland, Oregon, in the year 2002. Portland has three million inhabitants and continuous rain. It is deprived enough for the poorer inhabitants to have kwashiorkor, a protein deprivation from malnutrition. Although impoverished, the culture is similar to the 1970s in the United States. There is also a massive war in the Middle East. Climate change reduces quality of life.

George Orr, a draftsman and addict, abuses drugs to prevent "effective" dreams that change reality. After one of these dreams, the new reality is the only reality for everyone else, but Orr retains memory of the previous reality. Under threat of incarceration, Orr undergoes treatment for his addiction, attending therapy sessions with ambitious psychiatrist and sleep researcher William Haber. Haber, gradually believing Orr's claims that his "effective" dreams can affect the waking world, seeks to use Orr's power to change the planet. His experiments with a biofeedback/EEG machine, nicknamed the Augmentor, enhance Orr's abilities while producing a series of increasingly intolerable alternative worlds based on an assortment of utopian (and dystopian) premises:

- Eliminating over-population is disastrous after Orr dreams that a devastating plague eliminated most humans.

- Attempting to remove the scourge of cancer from society creates a world where citizens are routinely allowed to euthanize one another for being considered a threat to the gene pool.

- "Peace on Earth" results in an alien invasion of the Moon, uniting mankind against the external threat while creating new conflict in "cislunar space".

- Eliminating racism causes all humans to have gray skin, and changes much of history: "...he had searched his memory and had found in it no address that had been delivered on a battlefield in Gettysburg, nor any man known to history named Martin Luther King" (LeGuin, 130).[6]

Each effective dream gives Haber more wealth and status until he is effectively ruler of the planet. Orr's finances also improve, but he is unhappy with Haber's meddling and just wants to let things be. Increasingly frightened by Haber's lust for power and delusions of divinity, Orr contacts lawyer Heather Lelache to represent him against Haber. He falls in love with Heather but is unsuccessful in getting released from therapy. Despite this failure, Lelache is able to be present at one of the sessions, which allows her to remember two realities: one where her husband died early in the Middle East War and another where he died just before the truce because of the aliens. She seeks out Orr after he attempts to escape Haber by fleeing to the countryside, where he reveals to her that the world was destroyed by a nuclear war in April 1998. Orr dreamed it back into existence as he lay dying in the ruins, and doubts the reality of what now exists, considering it nothing more than a mere dream.

Portland and Mount Hood play a central role in the setting of the novel

Afraid of the potential harm Haber could do to reality and frustrated by his refusal to admit to Orr that he knows the power of his effective dreams, Orr believes that his only option may be to commit suicide. Lelache suggests that she assist him in dreaming an effective dream to make Haber more benevolent instead, to which he eventually agrees. She tries to help Orr but also tries to improve the planet; when she suggests to a dreaming Orr that the aliens should no longer be on the Moon, they invade the Earth instead. In the resultant fighting, Mount Hood is bombed and the 'dormant' volcano produces a spectacular eruption.

During that disaster, Orr returns to Haber, who has Orr dream of peaceful aliens. For a time, everybody experiences stability, but Haber continues meddling. His suggestion Orr dream away racism results in everyone becoming gray; Lelache's parents are different races, so she never existed in that alternative reality. Orr dreams a gray version of her with a milder personality; the two marry. Mount Hood continues to erupt, and he is concerned the planet is losing coherence.

After speaking with one of the aliens, who seem to have a cryptic understanding of the effective dreams, Orr suddenly understands his situation and confronts Haber. In their final session, Haber "cures" Orr of his ability to dream effectively by suggesting Orr dream that his dreams no longer affect reality. Haber has become frustrated with Orr's resistance and used his research from studying Orr's brain during his sessions to give himself the same power. Haber's first effective dream represents a significant break with the various realities created by Orr, and threatens to destroy reality. Despite Orr's efforts to prevent it, the gray Lelache is annihilated by the encroaching chaos. Orr successfully shuts off the Augmentor as coherent existence threatens to dissolve into undifferentiated chaos. The world is saved, but exists now as a mix of random elements from several realities.

In the new reality, Orr works at a kitchen store operated by one of the aliens. Haber survives, his mind shattered by his knowledge of unreality, and only exists because Orr's dreams restored him. Lelache is also restored, though she is left with only a slight memory of Orr. Orr is resigned to the loss of the Lelache he loved, but resolves to romance the one that exists now. The story ends as the two have coffee, while his inscrutable alien employer observes.

Theodore Sturgeon, reviewing Lathe for The New York Times, found it to be "a very good book," praising Le Guin for "produc[ing] a rare and powerful synthesis of poetry and science, reason and emotion."[7] Lester del Rey, however, faulted the novel for an arbitrary and ineffective second half, saying "with wonder piled on wonder, the plot simply loses credibility."[8]

"One of the best novels, and most important to understanding of the nature of our world, is Ursula Le Guin's The Lathe of Heaven, in which the dream universe is articulated in such a striking and compelling way that I hesitate to add any further explanation to it; it requires none."

Philip K. Dick

Although technology plays a minor role, the novel is concerned with philosophical questions about our desire to control our destiny, with Haber's positivist approach pitted against a Taoist equanimity. The beginnings of the chapters also feature quotes from H. G. Wells, Victor Hugo and Taoist sages. Due to its portrayal of psychologically derived alternative realities, the story is described as Le Guin's tribute to Philip K. Dick.[9] In his biography of Dick, Lawrence Sutin described Le Guin as having "long been a staunch public advocate of Phil's talent". According to Sutin, "The Lathe of Heaven was, by her acknowledgment, influenced by his [Dick's] sixties works."[10]

The book is critical of behaviorism.[11] Orr, a deceptively mild yet very strong and honest man, is labeled sick because he is immensely frightened by his ability to change reality. He is forced to undergo treatment. His efforts to get rid of Haber are viewed as suspect because he is a psychiatric patient. Haber, meanwhile, is very charming, extroverted, and confident, yet he eventually goes insane and almost destroys reality. He dismisses Orr's qualms about meddling with reality with paternalistic psychobabble, and is more concerned with his machine and Orr's powers than with curing his patient.

The book is also critical of the philosophy of utilitarianism, satirising the phrase "The Greatest Happiness for the Greatest Number." It is critical of eugenics, which it suggests would be a key feature of a culture based on utilitarian ethics.

It has been suggested that Le Guin named her protagonist "George Orr" as an homage to British author George Orwell, as well as to draw comparisons between the dystopic worlds she describes in Lathe and the dystopia Orwell envisioned in his novel 1984. It might also have the additional meaning either / or.[12]

An adaptation titled The Lathe of Heaven, produced by the public television station WNET, and directed by David Loxton and Fred Barzyk, was released in 1980. It was the first direct-to-TV film production by Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and was produced with a budget of $250,000. Generally faithful to the novel, it stars Bruce Davison as George Orr, Kevin Conway as William Haber, and Margaret Avery as Heather Lelache. Le Guin was heavily involved in the production of the 1980 adaptation, and expressed her satisfaction with it several times.[4][13]

PBS' rights to rebroadcast the film expired in 1988, and it became the most-requested program in PBS history. Fans were extremely critical of WNET's supposed "warehousing" of the film, but the budgetary barriers to rebroadcast were high: The station needed to pay for and clear rights with all participants in the original program; negotiate a special agreement with the composer of the film's score; and deal with The Beatles recording excerpted in the original soundtrack, "With a Little Help from My Friends", which is an integral plot point in both the novel and the film. A cover version replaces the Beatles' own recording in the home video release.

The home video release is remastered from a video tape of the original broadcast. PBS, anticipating that the rights issues would beset the production forever, did not save a copy of the film production in their archives.

A second adaptation was released in 2002 and retitled Lathe of Heaven. Produced for the A&E Network and directed by Philip Haas, the film starred James Caan, Lukas Haas, and Lisa Bonet. The 2002 adaptation discards a significant portion of the plot and some of the characters. Le Guin had no involvement in making the film.[14]

A stage adaptation by Edward Einhorn, produced by Untitled Theater Company #61, ran from June 6 to June 30, 2012, at the 3LD Art + Technology Center in New York City.[15]

Publication history

[edit]

Serialized

- Amazing Science Fiction Stories, March 1971 and May 1971.

Editions in English

- 1971, US, Charles Scribner's Sons, ISBN 0-684-12529-3, hardcover

- 1971, US, Avon Books, ISBN 0-380-43547-0, paperback

- 1972, UK, Victor Gollancz, ISBN 0-575-01385-0, hardcover

- 1974, UK, Panther Science Fiction, ISBN 0-586-03841-8, paperback (reprinted 1984 by Granada Publishing)

- 1984, US, Avon Books, ISBN 0-380-01320-7, paperback (reprinted 1989)

- 1997, US, Avon Books, ISBN 0-380-79185-4, trade paperback

- 2001, US, Millennium Books, ISBN 1-85798-951-1, paperback

- 2003, US, Perennial Classics, ISBN 0-06-051274-1, paperback

- 2008, US, Scribner, ISBN 1-4165-5696-6, paperback

- 2014, US, Diversion Books, ISBN 978-16268126-2-8, eBook

Audio recording in English

- 1999, US, Blackstone Audio Books, ISBN 0-7861-1471-1

Translations

- 1971, France: L'autre côté du rêve, Marabout; reprinted in 2002 by Le Livre de Poche, ISBN 2-253-07243-5

- 1974, Germany, Die Geißel des Himmels, Heyne, München, 1974, ISBN 3-453-30250-8

- 1975, Argentina, La rueda del cielo, Grupo Editor de Buenos Aires.

- 1979, Sweden: På Andra Sidan Drömmen, Kindbergs Förlag, ISBN 91-85668-01-X

- 1983, Portugal: O Flagelo dos Céus, Publicações Europa-América

- 1987, Spain, La rueda celeste, Minotauro, Barcelona, 1987; reprinted in 2017 ISBN 978-84-350-0784-9

- 1987, Serbia: Nebeski strug, Zoroaster

- 1991, Finland: Taivaan työkalu, Book Studio, ISBN 951-611-408-3

- 1991, Poland: Jesteśmy snem, Phantom Press, ISBN 83-7075-210-1 & 83-900214-1-2

- 1991, Portugal: Do Outro Lado do Sonho, Edições 70, ISBN 972-44-0784-5

- 1992, Hungary: Égi eszterga, Móra, ISBN 963-11-6867-0

- 1994, Czech Republic: Smrtonosné sny, Ivo Železný, ISBN 80-7116-173-X

- 1997, Russia: Резец небесный

- 2004, Portugal: O Tormento dos Céus, Editorial Presença, ISBN 972-23-3156-6

- 2005, Italy: La Falce dei cieli, Editrice Nord, ISBN 88-429-1360-X

- 2010, Korea: 하늘의 물레.황금가지, ISBN 978-89-6017-242-5

- 2011, Turkey: Rüyanın Öte Yakası, Metis Yayınları, ISBN 978-97-5342-791-3

- 2013, Romania: Sfâșierea cerului, Editura Trei, ISBN 978-973-707-723-3

- Eye in the Sky

- The Man in the High Castle

- The Futurological Congress

- The Tombs of Atuan

- The Word for World Is Forest

- Paprika

- Psychokinesis

- Utopian and dystopian fiction

Notes

- ^ a b "1972 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ^ "1971 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ^ Chai, David I. (2014). Nothingness, Being, and Dao: Ontology and Cosmology in the Zhuangzi. University of Toronto. p. 193. S2CID 125591433.

- ^ a b Issued as bonus material on New Video's 2000 release of The Lathe of Heaven, ISBN 0-7670-2696-9. The "lathe" discussion appears at 8:07—9:05.

- ^ Lao Tzu Tao Te Ching, A book about the Way and the power of the Way, Ursula Le Guin, p. 108 of the version edited by Shambhala Publications, Inc., 9/97

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K.; Link, Kelly (2023). The lathe of heaven (Scribner ed.). New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-6680-1740-1.

- ^ "If . . .?", The New York Times, May 14, 1972.

- ^ "Reading Room", If, April 1972, p.121-22

- ^ Watson, Ian (Mar 1975). "Le Guin's Lathe of Heaven and the Role of Dick: The False Reality as Mediator". Science Fiction Studies. 2 (5). SF-TH Inc.: 67–75. See also: Ashley, Michael (2000). Gateways to Forever: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines, 1970–1980 (2nd ed.). Liverpool University Press. pp. 75–77. ISBN 1-84631-002-4.

- ^ Sutin, Lawrence (2005) [1989]. Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 276. ISBN 0-7867-1623-1.

- ^ Bucknall 1981, p.90

- ^ Wilcox, Clyde (1997). Political Science Fiction. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-113-7. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "Ursula K Le Guin.com: The Lathe of Heaven". ursulakleguin.com. Archived from the original on 2007-08-12. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ "Ursula K. Le Guin: Note on the remake of Lathe of Heaven". Archived from the original on 2007-08-12. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ^ "Untitled Theater Company #61". Archived from the original on 2015-01-09. Retrieved 2012-09-09.

Bibliography

Barbour, Douglas (Nov 1973). "The Lathe of Heaven: Taoist Dream". Algol (21). Andrew I. Porter: 22–24.

Bernardo, Susan M.; Murphy, Graham J. (2006). Ursula K. Le Guin: A Critical Companion (1st ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33225-8.

Bloom, Harold, ed. (1986). Ursula K. Le Guin. Modern Critical Views. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-87754-659-2.

Bucknall, Barbara J. (1981). Ursula K. Le Guin. Recognitions. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8044-2085-8.

Cadden, Mike (2005). Ursula K. Le Guin Beyond Genre: Fiction for Children and Adults (1st ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-99527-2.

Cummins, Elizabeth (Jul 1990). "The Land-Lady's Homebirth: Revisiting Ursula K. Le Guin's Worlds". Science Fiction Studies. 17 (51). SF-TH Inc.: 153–166.

Cummins, Elizabeth (1993). Understanding Ursula K. Le Guin (2nd ed.). University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-869-7.

Franko, Carol S. (1996). "The I-We Dilemma and a "Utopian Unconscious" in Well's When the Sleeper Wakes and Le Guin's The Lathe of Heaven". Political Science Fiction. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 76–98. ISBN 1-57003-113-4.

Huang, Betsy (Winter 2008). "Premodern Orientalist Science Fictions". MELUS. 33 (4). University of Connecticut: 23–43. doi:10.1093/melus/33.4.23. ISSN 0163-755X.

Jameson, Fredric (Jul 1982). "Progress Versus Utopia; or, Can We Imagine the Future?". Science Fiction Studies. 9 (27). SF-TH Inc.: 147–158.

Jameson, Fredric (2005). Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. Verso. ISBN 1-84467-033-3.

Malmgren, Carl D. (1998). "Orr Else? The Protagonists of Le Guin's The Lathe of Heaven". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 9 (4). Idaho State University: International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts: 59–69. ISSN 0897-0521.

The Lathe of Heaven title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Review by Science Fiction Weekly Archived 2009-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

The Lathe of Heaven Archived 2010-03-23 at the Wayback Machine, reviewed by Ted Gioia (Conceptual Fiction Archived 2021-04-21 at the Wayback Machine)

The Lathe of Heaven at Worlds Without End

A translation of the works of Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zhou) is available on-line.