The Outline of History (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1919–1920 book by H. G. Wells

The Outline of History

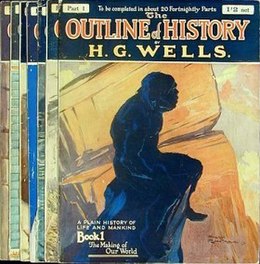

Book cover of The Outline of History [The Making of Our World] (first edition, 1920) Book cover of The Outline of History [The Making of Our World] (first edition, 1920) |

|

|---|---|

| Author | H. G. Wells |

| Illustrator | J. F. Horrabin |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | George Newnes |

| Publication date | 1919–20 |

| Text | The Outline of History at Wikisource |

The Outline of History, subtitled either "The Whole Story of Man" or "Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind", is a work by H. G. Wells chronicling the history of the world from the origin of the Earth to the First World War. It appeared in an illustrated version of 24 fortnightly installments beginning on 22 November 1919 and was published as a single volume in 1920.[1][2] It sold more than two million copies, was translated into many languages, and had a considerable impact on the teaching of history in institutions of higher education.[3] Wells modelled the Outline on the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot.[4]

Many revised versions were published during Wells's lifetime, and the author kept notes on factual corrections which he received from around the world. The last revision which was published during his lifetime was published in 1937.

In 1949, an expanded version was produced by Raymond Postgate, who extended the narrative so it could include the Second World War, and later, he published another version which extended the narrative up to 1969. Postgate wrote that "readers wish to hear the views of Wells, not those of Postgate," and he endeavoured to preserve Wells's voice throughout the narrative. In later editions G. P. Wells, the author's son, updated the early chapters about prehistory in order to make them reflect current theories: previous editions had, for instance, given credence to Piltdown Man before it was exposed as a hoax. The final edition appeared in 1971, but earlier editions are still in print.

Organization of the work

[edit]

The third revised and rearranged edition is organized in chapters whose subjects are as follows:

- Ch. 1–2: The origins of the Earth

- Ch. 3–6: Natural selection and the evolution of life

- Ch. 7: Human origins

- Ch. 8: Neanderthals and the early Paleolithic Age

- Ch. 9: The later Paleolithic Age

- Ch. 10: The Neolithic Age

- Ch. 11: Early (prelinguistic) thought

- Ch. 12: Races

- Ch. 13: Languages

- Ch. 14: The first civilizations

- Ch. 15: Sea voyages and trading

- Ch. 16: Writing

- Ch. 17: Organized religion

- Ch. 18: Social classes

- Ch. 19: The Hebrews

- Ch. 20: Aryan-speaking (or Indo-European-speaking) peoples

- Ch. 21–23: The Ancient Greeks

- Ch. 24: Alexandria

- Ch. 25: Buddhism

- Ch. 26–28: Rome

- Ch. 29: Christianity

- Ch. 30: Asia (50 BC – AD 650)

- Ch. 31: Islam

- Ch. 32: The Crusades

- Ch. 33: The Mongols

- Ch. 34: The Renaissance in Western Europe

- Ch. 35: Political developments, including that of the great power

- Ch. 36: The American and French revolutions

- Ch. 37: Napoleon

- Ch. 38: The Nineteenth century

- Ch. 39: The Great War

- Ch. 40: The Next Stage of History.

History as a quest for a common purpose

[edit]

From Neolithic times (12,000–10,000 years ago, by Wells's estimation) "[t]he history of mankind . . . is a history of more or less blind endeavours to conceive a common purpose in relation to which all men may live happily, and to create and develop a common stock of knowledge which may serve and illuminate that purpose."[5]

Recurrent conquest of civilization by nomads

[edit]

Wells was uncertain whether to place "the beginnings of settled communities living in towns" in Mesopotamia or Egypt.[6] He was equally unsure whether to consider the development of civilization as something that arose from "the widely diffused Heliolithic Neolithic culture" or something that arose separately.[7] Between the nomadic cultures that originated in the Neolithic Age and the settled civilizations to the south, he discerned that "for many thousands of years there has been an almost rhythmic recurrence of conquest of the civilizations by the nomads."[8] According to Wells, this dialectical antagonism reflected not only a struggle for power and resources, but a conflict of values: "Civilization, as this outline has shown, arose as a community of obedience, and was essentially a community of obedience. But . . . [t]here was a continual influx of masterful will from the forests, parklands, and steppes. The human spirit had at last rebelled altogether against the blind obedience of the common life; it was seeking . . . to achieve a new and better sort of civilization that should also be a community of will."[9] Wells regarded the democratic movements of modernity as an aspect of this movement.[10]

Development of free intelligence

[edit]

Wells saw in the bards who were, he believed, common to all the "Aryan-speaking peoples" an important "consequence of and a further factor in [the] development of spoken language which was the chief factor of all the human advances made in Neolithic times. . . . they mark a new step forward in the power and range of the human mind," extending the temporal horizons of the human imagination.[11] He saw in the ancient Greeks another definitive advance of these capacities, "the beginnings of what is becoming at last nowadays a dominant power in human affairs, the 'free intelligence of mankind'."[12] The first individual he distinguishes as embodying free intelligence is the Greek historian Herodotus.[13] The Hebrew prophets and the tradition they founded he calls "a parallel development of the free conscience of mankind."[14] Much later, he singles out Roger Bacon as a precursor of "a great movement in Europe . . . toward reality" that contributed to the development of "intelligence".[15] But "[i]t was only in the eighties of the nineteenth century that this body of inquiry began to yield results to impress the vulgar mind. Then suddenly came electric light and electric traction, and the transmutation of forces, the possibility of sending power . . . began to come through to the ideas of ordinary people."[16]

Rejection of racial or cultural superiority

[edit]

Although a few passages in The Outline of History reflect racialist thinking, Wells firmly rejected all theories of racial and civilizational superiority. On the subject of race, Wells writes that "Mankind from the point of view of a biologist is an animal species in a state of arrested differentiation and possible admixture . . . [A]ll races are more or less mixed.".[17] As for the claim that Western minds are superior, he states that upon examination "this generalization . . . dissolves into thin air."[18]

Omitted aspects of world history

[edit]

A number of themes are downplayed in The Outline of History: Ancient Greek philosophy and Roman law figure among these. Others are altogether absent, in spite of Wells's own intellectual attachment to some of them: romanticism, the concept of the Age of Enlightenment and feminism, for example.

Composition of the work

[edit]

Wells's methodology

[edit]

In the years leading up to the writing of The Outline of History, Wells was increasingly preoccupied by history, as many works testify. (See, for example, The New Machiavelli, Marriage, An Englishman Looks at the World, The Wife of Sir Isaac Harman, Mr. Britling Sees It Through, etc.) During World War I, he tried to promote a world history to be sponsored by the League of Nations Union, of which he was a member. But no professional historian would commit to undertake it, and Wells, in a financially sound position thanks to the success of Mr. Britling Sees It Through and believing that his work would earn little, resolved to devote a year to the project. His wife Catherine (Jane) agreed to be his collaborator in typing, research, organization, correspondence, and criticism. Wells relied heavily on the Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed., 1911), and standard secondary texts. He made use of the London Library, and enlisted as critical readers "a team of advisers for comment and correction, chief among them Ernest Barker, Harry Johnston, E. Ray Lankester, and Gilbert Murray. The sections were then rewritten and circulated for further discussion until Wells judged that they had reached a satisfactory standard."[19] The bulk of the work was written between October 1918 and November 1919.

Rejected allegations of plagiarism

[edit]

In 1927 a Canadian, Florence Deeks, sued Wells for infringement of copyright and breach of trust. She claimed that he had plagiarized much of the content of The Outline of History from her work, The Web of the World's Romance. She had submitted her manuscript to the Canadian publisher Macmillan Canada, which was Wells's Canadian publisher. Macmillan Canada had the manuscript for nearly nine months before rejecting it.

At trial in the Supreme Court of Ontario, Deeks called called three literary academics as experts, who testified that the content and structure of the two books showed that Wells must have relied on Deeks's manuscript in writing The Outline of History. Wells testified, and denied that he had ever seen Deeks's manuscript, while representatives from Macmillan testified that the manuscript had never left Canada. The trial judge rejected Deeks's expert evidence and dismissed the case.[20] An appeal to the Ontario Appellate Division was dismissed,[21] as was a final appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council,[22] at that time the highest court of appeal for the British Empire.[23]

In 2000, A. B. McKillop a professor of history at Carleton University, Ottawa, wrote a book entitled The Spinster & the Prophet: Florence Deeks, H. G. Wells, and the Mystery of the Purloined Past, which examined the legal case brought by Deeks. McKillop's thesis was that Deeks did not receive fair treatment from the courts, which he argued heavily favoured men at that time, both in Canada and in Britain.[24]

In 2004 Denis N. Magnusson, professor emeritus in the Faculty of Law, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, published an article on Deeks v. Wells in the Queen's Law Journal. He took issue with McKillop's position, arguing that Deeks had a weak case that was not well presented, and though she may have met with sexism from her lawyers, she did receive a fair trial. He argued that the law applied in the case was essentially the same law that would be applied to a similar case in 2004.[23]

The Outline of History has inspired responses from the serious to the parodic.

- In 1921 Algonquin Round Table member Donald Ogden Stewart achieved his first success with a satire entitled A Parody Outline of History.

- The Outline of History was praised on publication by E. M. Forster and Beatrice Webb.[25]

- Edward Shanks described The Outline as "a wonderful book". However, he also criticized what he saw as Wells's "impatience" and stated "it is an unfortunate fact that Mr. Wells often seems to find himself in the position of scold to the entire human race".[26]

- American historians James Harvey Robinson and Carl Becker lauded the Outline and hailed Wells as "a formidable ally".[27]

- In 1925 G. K. Chesterton, wrote The Everlasting Man, a critique of The Outline of History from a Catholic perspective.[28]

- In 1926 Hilaire Belloc wrote "A Companion to Mr. Wells's Outline of History". A devout Catholic, Belloc was deeply offended by Wells's treatment of Christianity in The Outline of History. Wells wrote a short book in rebuttal called Mr. Belloc Objects to "The Outline of History". In 1926, Belloc published his reply, Mr. Belloc Still Objects.[29]

- In 1934 Arnold J. Toynbee dismissed the criticism of The Outline of History and praised Wells's work in his A Study of History:

Mr. H. G. Wells's The Outline of History was received with unmistakable hostility by a number of historical specialists. . . . They seemed not to realize that, in re-living the entire life of Mankind as a single imaginative experience, Mr. Wells was achieving something which they themselves would hardly have dared to attempt ... In fact, the purpose and value of Mr. Wells's book seem to have been better appreciated by the general public than by the professional historians of the day.[30]

Toynbee went on to refer to The Outline several times in A Study of History, offering his share of criticism but maintaining a generally positive view of the book. - Also in 1934 Jawaharlal Nehru stated that The Outline of History was a major influence on his own work, Glimpses of World History.[31]

- After Wells's death The Outline was still the object of admiration from historians A. J. P. Taylor (who called it "the best" general survey of history) and Norman Stone, who praised Wells for largely avoiding the Eurocentric and racist attitudes of his time.[32]

- In his autobiography Christopher Isherwood recalled that when he and W. H. Auden encountered Napoleon's tomb on a 1922 school trip to France, their first reaction was to quote The Outline's negative assessment of the French ruler.[33]

- Malham Wakin, head of the philosophy department at the United States Air Force Academy, encouraged his students to consider and challenge a statement made by Wells in The Outline of History: "The professional military mind is by necessity an inferior and unimaginative mind; no man of high intellectual quality would willingly imprison his gifts in such a calling."[34][35]

The Outline of History was one of the first of Wells' books to be banned in Nazi Germany.[36]

- In Dashiell Hammett's 1930 book The Maltese Falcon Casper Gutman says, "These are facts, historical facts, not schoolbook history, not Mr. Wells's history, but history nevertheless."

- In Virginia Woolf's posthumously published 1941 novel Between the Acts the character Lucy Swithin reads a book entitled The Outline of History.

- In John Huston's 1941 film The Maltese Falcon Kasper Gutman played by Sydney Greenstreet says "These are facts, historical facts, not schoolbook history, not Mr. Wells's history, but history nevertheless."[37]

- In Fredric Brown's 1949 science-fiction novel What Mad Universe the protagonist finds himself transported to an alternate universe. Finding a copy of Wells's Outline of History, it turns out to be identical to the one he knows until 1903, at which point the alternate Wells records the invention of anti-gravity, a fast human expansion into space, a brutal war for the conquest of Mars which Wells strongly denounces, followed by a titanic conflict with Arcturus.

- In Satyajit Ray's 1959 film The World of Apu the book, wrapped in a white cloth cover with only the title visible, is seen on the bookshelf of the protagonist Apurba Roy.

- In John Updike's 1961 story "Pigeon Feathers" the young protagonist finds a copy of Outline of History and is surprised and disturbed by Wells's descriptions of Jesus. Updike describes Wells's account of Jesus as:

He had been an obscure political agitator, a kind of hobo, in a minor colony of the Roman Empire. By an accident impossible to reconstruct, he (the small h horrified David) survived his own crucifixion and presumably died a few weeks later. A religion was founded on the freakish incident. The credulous imagination of the times retrospectively assigned miracles and supernatural pretensions to Jesus; a myth grew, and then a church, whose theology at most points was in direct contradiction of the simple, rather communistic teachings of the Galilean.[38]

- William Golding used Wells's description of the Neanderthals as a basis in creating his own Neanderthal tribe in his 1955 novel, The Inheritors.[39]

- A Short History of the World (Wells book)

- Guns, Germs, and Steel (Jared Diamond)

Notes and references

[edit]

- ^ Wells, H.G. (1920). The Outline of History: Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind. Vol. I (1 ed.). New York: Macmillan. Retrieved 1 July 2016 – via Internet Archive.; Wells, H.G. (1920). The Outline of History: Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind. Vol. II (1 ed.). New York: Macmillan. Retrieved 1 July 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010), p. 252.

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010), p. 252-53; David C. Smith, H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal: A Biography (Yale University Press, 1986), pp. 258–60.

- ^ H.G. Wells, World Brain, Garden City, Doubleday Doran, 1938 (p. 20).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 104 (Ch. XI, §6).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 131 (Ch. XIV, §1).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), pp. 131–32 (Ch. XIV, §1).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 246 (Ch. XX, §3).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 843 (Ch. XXVI, §5).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), pp. 842–43 (Ch. XXVI, §5).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 243 (Ch. XX, §2).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 204 (Ch. XVIII, §3) (emphasis in original).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 202 (Ch. XVIII, §3).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 234 (Ch. XIX, §4).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), pp. 729–33 (Ch. XXXIV, §6).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 927 (Ch. XXXVIII, §1).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 110 (Ch. XII, §§1–2).

- ^ H.G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 556 (Ch. XXX, §8).

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010), p. 252.

- ^ Deeks v. Wells, 1930 CanLII 786, 167 [1930] 4 D.L.R. 513 (Ont. S.C.).

- ^ Deeks v. Wells, 1931 CanLII 157, [1931] 4 D.L.R. 533 (Ont. S.C. App.Div.).

- ^ Deeks v Wells, [1932] UKPC 66, 1932 CanLII 315, [1933] 1 DLR 353.

- ^ a b Magnusson, Denis N. (Spring 2004). "Hell Hath No Fury: Copyright Lawyers' Lessons from Deeks v. Wells". Queen's Law Journal. 29: 680, 684.

- ^ A.B. McKillop, The Spinster and the Prophet (Four Walls Eight Windows, 2000).

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010)

- ^ Edward Shanks, "The Work of Mr. H.G. Wells". London Mercury, March–April 1922. Reprinted in Patrick Parrinder, H.G. Wells : The Critical Heritage. London; Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1997. ISBN 0415159105 (p.255-257)

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010)

- ^ Dale, Alzina Stone, _The Outline of Sanity : A Biography of G.K. Chesterton_Grand Rapids, Mich. : Eerdmans, 1982. ISBN 9780802835505 (p. 248)

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010).

- ^ Toynbee, A.J. A Study of History, Vol I, Oxford University Press, 1934.

- ^ Nehru, Jawaharlal. Glimpses of World History, vii. New York City: John Day Company, 1942.

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010)

- ^ Isherwood, Christopher, Lions and Shadows, 1938. New English Library edition, 1974, pg. 18.

- ^ Wakin, Malham (2000). Integrity First: Reflections of a Military Philosopher. Lexington Books. p. 3. ISBN 0739101706. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "A Gallery of Great Professors Agree That An Interested Student Is What Their Job Is About". People. 13 October 1975. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Alex."From Hemingway to HG Wells: The books banned and burnt by the Nazis" The Independent, 8 August 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ IMDb: The Maltese Falcon (1941) – Memorable quotes

- ^ Updike, John (2003). The Early Stories 1953–1975. New York: Random House. p. 14. ISBN 0-345-46336-6. Note, however, that Wells does not assert (at least in the 3rd revised edition of The Outline of History) that Jesus "survived his own crucifixion and presumably died a few weeks later"; rather, Wells says that after Jesus's death and burial "presently came a whisper among [the disciples] and stories, rather discrepant stories . . ." (see Ch. XXIX, §4).

- ^ The Art of William Golding, p. 47, at Google Books

- Dawson, Christopher. "H. G. Wells and the Outline of History" History Today (Oct 1951) 1#10 pp 28–32

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Full text of the 1920 edition of The Outline of History

- PDF versions of the 1971 edition of the text: Volume One, Volume Two via Internet Archive

- The Outline of History at Project Gutenberg

- Salon.com's review of A. B. McKillop's examination of the Deeks/Wells plagiarism case, The Spinster and the Prophet.