Toxic shock syndrome (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Medical condition caused by bacterial toxins

Medical condition

| Toxic shock syndrome | |

|---|---|

|

|

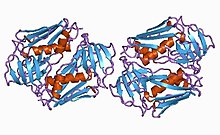

| Toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 protein from staphylococcus | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, rash, skin peeling, low blood pressure[1] |

| Complications | Shock, kidney failure[2] |

| Usual onset | Rapid[1] |

| Types | Staphylococcal (menstrual and nonmenstrual), streptococcal[1] |

| Causes | Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, others[1][3] |

| Risk factors | Very absorbent tampons, skin lesions in young children[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Septic shock, Kawasaki's disease, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, scarlet fever[4] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, incision and drainage of any abscesses, intravenous immunoglobulin[1] |

| Prognosis | Risk of death: ~50% (streptococcal), ~5% (staphylococcal)[1] |

| Frequency | Staphylococcal: 0.3 to 0.5 cases per 100,000 populationStreptococcal: 2 to 4 cases per 100,000 population |

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a condition caused by bacterial toxins.[1] Symptoms may include fever, rash, skin peeling, and low blood pressure.[1] There may also be symptoms related to the specific underlying infection such as mastitis, osteomyelitis, necrotising fasciitis, or pneumonia.[1]

TSS is typically caused by bacteria of the Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus type, though others may also be involved.[1][3] Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome is sometimes referred to as toxic-shock-like syndrome (TSLS).[1] The underlying mechanism involves the production of superantigens during an invasive streptococcus infection or a localized staphylococcus infection.[1] Risk factors for the staphylococcal type include the use of very absorbent tampons, skin lesions in young children characterized by fever, low blood pressure, rash, vomiting and/or diarrhea, and multiorgan failure.[1][5][6] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms.[1]

Treatment includes intravenous fluids, antibiotics, incision and drainage of any abscesses, and possibly intravenous immunoglobulin.[1][7] The need for rapid removal of infected tissue via surgery in those with a streptococcal cause, while commonly recommended, is poorly supported by the evidence.[1] Some recommend delaying surgical debridement.[1] The overall risk of death is about 50% in streptococcal disease, and 5% in staphylococcal disease.[1] Death may occur within 2 days.[1]

In the United States, the incidence of menstrual staphylococcal TSS declined sharply in the 1990s, while both menstrual and nonmenstrual cases have stabilized at about 0.3 to 0.5 cases per 100,000 population.[1] Streptococcal TSS (STSS) saw a significant rise in the mid-1980s and has since remained stable at 2 to 4 cases per 100,000 population.[1] In the developing world, the number of cases is usually on the higher extreme.[1] TSS was first described in 1927.[1] It came to be associated with very absorbent tampons that were removed from sale soon after.[1]

Symptoms of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) vary depending on the underlying cause. TSS resulting from infection with the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus typically manifests in otherwise healthy individuals via signs and symptoms including high fever, accompanied by low blood pressure, malaise and confusion,[3] which can rapidly progress to stupor, coma, and multiple organ failure. The characteristic rash, often seen early in the course of illness, resembles a sunburn[3] (conversely, streptococcal TSS will rarely involve a sunburn-like rash), and can involve any region of the body including the lips, mouth, eyes, palms and soles of the feet.[3] In patients who survive, the rash desquamates (peels off) after 10–21 days.[3] The initial presentation of symptoms can be hard to differentiate from septic shock and other conditions such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever, rubeola, leptospirosis, drug toxicities, and viral exanthems.[8]

STSS caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes, or TSLS, typically presents in people with pre-existing skin infections with the bacteria. These individuals often experience severe pain at the site of the skin infection, followed by rapid progression of symptoms as described above for TSS.[9]

In both TSS (caused by S. aureus) and TSLS (caused by S. pyogenes), disease progression stems from a superantigen toxin. The toxin in S. aureus infections is TSS Toxin-1, or TSST-1. The TSST-1 is secreted as a single polypeptide chain. The gene encoding toxic shock syndrome toxin is carried by a mobile genetic element of S. aureus in the SaPI family of pathogenicity islands.[10] The toxin causes the non-specific binding of MHC II, on professional antigen presenting cells, with T-cell receptors, on T cells.

In typical T-cell recognition, an antigen is taken up by an antigen-presenting cell, processed, expressed on the cell surface in complex with class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in a groove formed by the alpha and beta chains of class II MHC, and recognized by an antigen-specific T-cell receptor. This results in polyclonal T-cell activation. Superantigens do not require processing by antigen-presenting cells but instead, interact directly with the invariant region of the class II MHC molecule.[11] In patients with TSS, up to 20% of the body's T-cells can be activated at one time. This polyclonal T-cell population causes a cytokine storm,[7] followed by a multisystem disease.

A few possible causes of toxic shock syndrome are:[12][13]

- Having strep throat or a viral infection like the flu or chickenpox

- Using tampons, especially if super-absorbent or left in longer than recommended

- Using contraceptive sponges, diaphragms or other devices placed inside the vagina

- History of a recent birth, miscarriage, or abortion

- Having a skin infection like impetigo or cellulitis

- Cuts or open wounds on the skin

- Surgical wounds

- Previously having TSS

For staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, the diagnosis is based upon CDC criteria defined in 2011, as follows:[5]

- Body temperature > 38.9 °C (102.0 °F)

- Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg

- Diffuse macular erythroderma

- Desquamation (especially of the palms and soles) 1–2 weeks after onset

- Involvement of three or more organ systems:

- Gastrointestinal (vomiting, diarrhea)

- Muscular: severe myalgia or creatine phosphokinase level at least twice the upper limit of normal for laboratory

- Mucous membrane hyperemia (vaginal, oral, conjunctival)

- Kidney failure (serum creatinine > 2 times normal)

- Liver inflammation (bilirubin, AST, or ALT > 2 times normal)

- Low platelet count (platelet count < 100,000 / mm3)

- Central nervous system involvement (confusion without any focal neurological findings)

- Negative results of:

- Blood, throat, and CSF cultures for other bacteria (besides S. aureus)

- Negative serology for Rickettsia infection, leptospirosis, and measles

Cases are classified as confirmed or probable as follows:

- Confirmed: All six of the criteria above are met (unless the patient dies before desquamation can occur)

- Probable: Five of the six criteria above are met

The severity of this disease frequently warrants hospitalization. Admission to the intensive care unit is often necessary for supportive care (for aggressive fluid management, ventilation, renal replacement therapy and inotropic support), particularly in the case of multiple organ failure.[14] Treatment includes removal or draining of the source of infection—often a tampon—and draining of abscesses. Outcomes are poorer in patients who do not have the source of infection removed.[14]

Antibiotic treatment should cover both S. pyogenes and S. aureus. This may include a combination of cephalosporins, penicillins or vancomycin. The addition of clindamycin[15] or gentamicin[16] reduces toxin production and mortality.

In some cases doctors will prescribe other treatments such as blood pressure medications (to stabilize blood pressure if it is too low), dialysis, oxygen mask (to stabilize oxygen levels), and sometimes a ventilator. These will sometimes be used to help treat side effects of contracting TSS.[12]

With proper treatment, people usually recover in two to three weeks. The condition can, however, be fatal within hours. TSS has a mortality rate of 30–70%. Children who are affected by TSS tend to recover easier than adults do.[17]

- Amputation of fingers, toes, and sometimes limbs[18]

- Death[2]

- Liver or kidney failure[2][19]

- Heart problems[19]

- Respiratory distress[19]

- Septic shock[12][2][4]

- Other abnormalities may occur depending on the case

During menstruation:[20]

- Use pads at night instead of tampons

- Try to keep up with changing a tampon every 4 to 8 hours

- Use low absorbent tampons

- Follow directions when using vaginal contraceptives (sponges or diaphragms)

- Make sure to maintain good hygiene during a menstrual cycle

For anyone:[21]

- Keep open wounds clean

- Watch wounds and cuts for signs of infection (e.g. pus, redness, and warm to touch)[12]

- Keep personal items personal (e.g.towels, sheets, razors)

- Wash clothing and bedding in hot water

Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome is rare and the number of reported cases has declined significantly since the 1980s. Patrick Schlievert, who published a study on it in 2004, determined incidence at three to four out of 100,000 tampon users per year; the information supplied by manufacturers of sanitary products such as Tampax and Stayfree puts it at one to 17 of every 100,000 menstruating females, per year.[22][23]

TSS was considered a sporadic disease that occurred in immunocompromised people. It was not a more well-known disease until the 1980s, when high-absorbency tampons were in use. Due to the idea of the tampons having a high absorbency this led users to believe that they could leave a tampon in for several hours. Doing this allowed the bacteria to grow and led to infection. This resulted in a spike of cases of TSS.[24]

Philip M. Tierno Jr. helped determine that tampons were behind TSS cases in the early 1980s. Tierno blames the introduction of higher-absorbency tampons in 1978. A study by Tierno also determined that all-cotton tampons were less likely to produce the conditions in which TSS can grow; this was done using a direct comparison of 20 brands of tampons including conventional cotton/rayon tampons and 100% organic cotton tampons from Natracare. In fact, Dr Tierno goes as far to state, "The bottom line is that you can get TSS with synthetic tampons, but not with an all-cotton tampon."[25]

A rise in reported cases occurred in the early 2000s: eight deaths from the syndrome in California in 2002 after three successive years of four deaths per year, and Schlievert's study found cases in part of Minnesota more than tripled from 2000 to 2003.[22] Schlievert considers earlier onset of menstruation to be a cause of the rise; others, such as Philip M. Tierno and Bruce A. Hanna, blame new high-absorbency tampons introduced in 1999 and manufacturers discontinuing warnings not to leave tampons in overnight.[22]

In Japan, Cases of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) reached 1,019 from January to June 2024, as compared to the 941 cases reported in 2023.[26][27]

TSS is more common during the winter and spring and occurs most often in the young and old.[3]

Toxic shock syndrome is commonly known to be an issue for those who menstruate, although fifty percent of Toxic Shock Syndrome cases are unrelated to menstruation. TSS in these cases can be caused by skin wounds, surgical sites, nasal packing, and burns.[20]

Awareness poster from 1985

Initial description

[edit]

The term "toxic shock syndrome" was first used in 1978 by a Denver pediatrician, James K. Todd, to describe the staphylococcal illness in three boys and four girls aged 8–17 years.[28] Even though S. aureus was isolated from mucosal sites in the patients, bacteria could not be isolated from the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or urine, raising suspicion that a toxin was involved. The authors of the study noted reports of similar staphylococcal illnesses had appeared occasionally as far back as 1927, but the authors at the time failed to consider the possibility of a connection between toxic shock syndrome and tampon use, as three of the girls who were menstruating when the illness developed were using tampons. Many cases of TSS occurred after tampons were left in after they should have been removed.[29]

Following controversial test marketing in Rochester, New York, and Fort Wayne, Indiana,[30] in August 1978, Procter and Gamble introduced superabsorbent Rely tampons to the United States market[31] in response to demands for tampons that could contain an entire menstrual flow without leaking or replacement.[32] Rely used carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) and compressed beads of polyester for absorption. This tampon design could absorb nearly 20 times its own weight in fluid.[33] Further, the tampon would "blossom" into a cup shape in the vagina to hold menstrual fluids without leakage.[34][35]

In January 1980, epidemiologists in Wisconsin and Minnesota reported the appearance of TSS, mostly in those menstruating, to the CDC.[36] S. aureus was successfully cultured from most of the subjects. The Toxic Shock Syndrome Task Force was created and investigated the epidemic as the number of reported cases rose throughout the summer of 1980.[37] In September 1980, CDC reported users of Rely were at increased risk for developing TSS.[38]

On 22 September 1980, Procter and Gamble recalled Rely[39] following release of the CDC report. As part of the voluntary recall, Procter and Gamble entered into a consent agreement with the FDA "providing for a program for notification to consumers and retrieval of the product from the market".[40] However, it was clear to other investigators that Rely was not the only culprit. Other regions of the United States saw increases in menstrual TSS before Rely was introduced.[41]

It was shown later that higher absorbency of tampons was associated with an increased risk for TSS, regardless of the chemical composition or the brand of the tampon. The sole exception was Rely, for which the risk for TSS was still higher when corrected for its absorbency.[42] The ability of carboxymethylcellulose to filter the S. aureus toxin that causes TSS may account for the increased risk associated with Rely.[33]

- Clive Barker, fully recovered, contracted the syndrome after visiting the dentist.[43]

- Lana Coc-Kroft, fully recovered, contracted the syndrome due to group A streptococcal infection.[44]

- Jim Henson, d. 1990, contracted the syndrome due to group A streptococcal infection and subsequently died from it.[45][46]

- Nan C. Robertson, d. 2009, the 1983 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing for Toxic Shock, her medically detailed account of her struggle with toxic shock syndrome, a cover story for The New York Times Magazine which at that time became the most widely syndicated article in Times history.[47][48]

- Barbara Robison, lead vocalist for the psychedelic rock band the Peanut Butter Conspiracy, was performing in Butte, Montana on 6 April 1988; during the concert, she fell ill and was transported to a hospital. She did not recover, and died sixteen days later on 22 April from toxic shock syndrome at the age of 42.[49]

- Mike Von Erich, d. 1987, developed the syndrome after shoulder surgery: he made an apparent recovery but experienced brain damage and weight loss as a result of the condition; he died by suicide later.[50]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Low DE (July 2013). "Toxic Shock Syndrome: Major Advances in Pathogenesis, But Not Treatment". Critical Care Clinics. 29 (3): 651–675. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2013.03.012. PMID 23830657 – via Elsevier.

- ^ a b c d "Toxic shock syndrome". Mayo Clinic. 23 March 2022. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A (June 2018). "The Evaluation and Management of Toxic Shock Syndrome in the Emergency Department: A Review of the Literature". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 54 (6): 807–814. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.12.048. PMID 29366615. S2CID 1812988.

- ^ a b Ferri FF (2010). Ferri's Differential Diagnosis: A Practical Guide to the Differential Diagnosis of Symptoms, Signs, and Clinical Disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby. p. 478. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ^ a b "Toxic shock syndrome (other than Streptococcal) (TSS): 2011 Case Definition". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 8 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Khajuria A, Nadam HH, Gallagher M, Jones I, Atkins J (2020). "Pediatric Toxic Shock Syndrome After a 7% Burn: A Case Study and Systematic Literature Review". Ann. Plast. Surg. 84 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000001990. PMID 31192868. S2CID 189815024.

- ^ a b Wilkins AL, Steer AC, Smeesters PR, Curtis N (2017). "Toxic shock syndrome – the seven Rs of management and treatment". Journal of Infection. 74: S147 – S152. doi:10.1016/S0163-4453(17)30206-2. PMID 28646955.

- ^ Burnham J, Kollef M (May 2015). "Understanding toxic shock syndrome". Intensive Care Medicine. 41 (9): 1707–1710. doi:10.1007/s00134-015-3861-7. PMID 25971393.

- ^ Bush LM (March 2023). "Toxic Shock Syndrome". The Merck Manuals. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ Lindsay JA, Ruzin, A, Ross, HF, Kurepina, N, Novick, RP (July 1998). "The gene for toxic shock toxin is carried by a family of mobile pathogenicity islands in Staphylococcus aureus". Molecular Microbiology. 29 (2): 527–43. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00947.x. PMID 9720870. S2CID 30680160.

- ^ Groisman EA, ed. (2001). "15. Pathogenic Mechanisms in Streptococcal Diseases". Principles of Bacterial Pathogenesis. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press. p. 740. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-304220-0.X5000-6. ISBN 978-0-12-304220-0. Archived from the original on 22 June 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024. Superantigens are proteins that have the ability to bind to an invariant region of the class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on an antigen-presenting cell and to crosslink this receptor to a T cell through binding to the variable region of the β-chain of the T cell antigen receptor.

- ^ a b c d "Sepsis and Toxic Shock Syndrome". Sepsis Alliance. 18 June 2024. Archived from the original on 24 June 2024. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "The Basics of Toxic Shock Syndrome". WebMD. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ a b Zimbelman J, Palmer A, Todd J (1999). "Improved outcome of clindamycin compared with beta-lactam antibiotic treatment for invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infection". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 18 (12): 1096–1100. doi:10.1097/00006454-199912000-00014. PMID 10608632. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Schlievert PM, Kelly JA (1984). "Clindamycin-induced suppression of toxic-shock syndrome-associated exotoxin production". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 149 (3): 471. doi:10.1093/infdis/149.3.471. PMID 6715902.

- ^ van Langevelde P, van Dissel JT, Meurs CJ, Renz J, Groeneveld PH (1 August 1997). "Combination of flucloxacillin and gentamicin inhibits toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 production by Staphylococcus aureus in both logarithmic and stationary phases of growth". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 41 (8): 1682–5. doi:10.1128/AAC.41.8.1682. PMC 163985. PMID 9257741.

- ^ "Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome: For Clinicians | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 23 November 2021. Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)". Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Toxic Shock Syndrome". National Organization for Rare Disorders. 8 April 2009. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS): Causes, Symptoms & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ "Staph infections – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Lyons JS (25 January 2005). "A New Generation Faces Toxic Shock Syndrome". The Seattle Times. Knight Ridder Newspapers. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017. first published as "Lingering Risk", San Jose Mercury News, 13 December 2004

- ^ "Stayfree — FAQ About Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)". 2006. Archived from the original on 23 March 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- ^ Mishra G (2014). "Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health". UQ eSpace. doi:10.14264/uql.2016.448. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Lindsey E (6 November 2003). "Welcome to the cotton club". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016.

- ^ Steedman E (21 June 2024). "Japan is dealing with a 'flesh-eating bacteria' outbreak. Here's what we know about STSS and how to avoid infection". ABC News. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Masih N, Vinall F (19 June 2024). "A deadly bacterial infection is on the rise in Japan. What is STSS?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Todd J, Fishaut M, Kapral F, Welch T (1978). "Toxic-shock syndrome associated with phage-group-I staphylococci". The Lancet. 2 (8100): 1116–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92274-2. PMID 82681. S2CID 54231145.

- ^ Todd J (1981). "Toxic shock syndrome—scientific uncertainty and the public media". Pediatrics. 67 (6): 921–3. doi:10.1542/peds.67.6.921. PMID 7232057. S2CID 3051129.

- ^ Finley, Harry. "Rely Tampon: It Even Absorbed the Worry!". Museum of Menstruation. Archived from the original on 14 April 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- ^ Hanrahan S, Submission HC (1994). "Historical review of menstrual toxic shock syndrome". Women & Health. 21 (2–3): 141–65. doi:10.1300/J013v21n02_09. PMID 8073784.

- ^ Citrinbaum, Joanna (14 October 2003). "The question's absorbing: 'Are tampons little white lies?'". The Daily Collegian. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ a b Vitale, Sidra (1997). "Toxic Shock Syndrome". Web by Women, for Women. Archived from the original on 16 March 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- ^ Vostral SL (27 November 2018). "5. Health Activism and the Limits of Labeling". Toxic Shock: A Social History. New York City: New York University Press. p. 140. doi:10.18574/nyu/9781479877843.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-4798-7784-3. LCCN 2018012210. OCLC 1031956695. Pursettes blossom out to absorb more fully, more effectively.

- ^ "No bulky applicator—Prelubricated tip". Ebony. 18 (9): 44. July 1963 – via Internet Archive. On contact with moisture, new Pursettes blossom out to absorb more fully, more effectively.

- ^ CDC (23 May 1980). "Toxic-shock syndrome—United States". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 29 (20): 229–230. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014.

- ^ Dennis Hevesi (10 September 2011). "Bruce Dan, Who Helped Link Toxic Shock and Tampons, Is Dead at 64". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ CDC (19 September 1980). "Follow-up on toxic-shock syndrome". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 29 (37): 441–5. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Hanrahan S, Submission HC (1994). "Historical review of menstrual toxic shock syndrome". Women & Health. 21 (2–3): 141–165. doi:10.1300/J013v21n02_09. PMID 8073784.

- ^ Kohen, Jamie (2001). "The History of the Regulation of Menstrual Tampons". LEDA at Harvard Law School. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ Petitti D, Reingold A, Chin J (1986). "The incidence of toxic shock syndrome in Northern California. 1972 through 1983". JAMA. 255 (3): 368–72. doi:10.1001/jama.255.3.368. PMID 3941516.

- ^ Berkley S, Hightower A, Broome C, Reingold A (1987). "The relationship of tampon characteristics to menstrual toxic shock syndrome". JAMA. 258 (7): 917–20. doi:10.1001/jama.258.7.917. PMID 3613021.

- ^ "Clive Barker recovering from 'near fatal' case of toxic shock syndrome". Entertainment Weekly. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Lang S (15 February 2009). "Lana's leap outside her comfort zone". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ^ Altman L (29 May 1990). "The Doctor's World; Henson Death Shows Danger of Pneumonia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 276–286. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ^ Robertson N (19 September 1982). "Toxic Shock". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Rupp CM. "The Times Goes Computer". In Ditlea S (ed.). Digital Deli. Atari Archives. Archived from the original on 27 August 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Talevski N (7 April 2010). Rock Obituaries – Knocking On Heaven's Door. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-117-2. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ Mercer B (2007). Play-by-Play: Tales from a Sportscasting Insider. Taylor Trade Publishing. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-1-4617-3474-1. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Stevens DL (1995). "Streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome: spectrum of disease, pathogenesis, and new concepts in treatment". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1 (3): 69–78. doi:10.3201/eid0103.950301. PMC 2626872. PMID 8903167.

- "Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS): The Facts". Toxic Shock Syndrome information service. tssis.com.