Wadjda (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

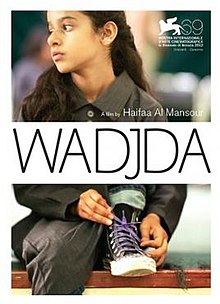

2012 Saudi Arabian film

| Wadjda وجدة | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Haifaa al-Mansour |

| Written by | Haifaa al-Mansour |

| Produced by | Gerhard Meixner Roman Paul |

| Starring | Waad Mohammed Reem Abdullah Abdulrahman al-Juhani |

| Cinematography | Lutz Reitemeier [de] |

| Edited by | Andreas Wodraschke |

| Music by | Max Richter |

| Productioncompanies | Rotana Studios Razor Film Produktion GmbH Norddeutscher Rundfunk Bayerischer Rundfunk Rotana TV Highlook Communications Group |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics Koch Media (Germany, all media) Rotana Studios |

| Release date | 31 August 2012 (2012-08-31) (Venice Film Festival) |

| Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | Saudi Arabia |

| Language | Arabic |

| Box office | $14.5 million[1] |

Wadjda (Arabic: وجدة, romanized: Wajda, pronounced [wad͡ʒ.da]) is a 2012 Saudi Arabian drama film, written and directed by Haifaa al-Mansour (in her feature directorial debut). It was the first feature film shot entirely in Saudi Arabia[2][3][4][5] and the first feature-length film made by a female Saudi director.[6][7] It won numerous awards at film festivals around the world. The film was selected as the Saudi Arabian entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 86th Academy Awards (the first time the country made a submission for the Oscars[8]), but it was not nominated.[9][10][11] It successfully earned a nomination for Best Foreign Film at the 2014 BAFTA Awards.

In the 2000s, Wadjda, a spirited 10-year-old living in Riyadh, dreams of owning a green bicycle that she passes at a store every day on her way to school. She wants to race her friend Abdullah, a boy from her neighborhood, but riding bikes is frowned upon for girls and Wadjda's mother refuses to buy one for her. The bike is expensive, costing SR800 (~$213).

Wadjda begins to earn the money herself by selling mixtapes, hand-braiding bracelets for classmates, and acting as a go-between for an older student. These activities get her into trouble with the strict headmistress. Her mother, meanwhile, is dealing with a job that has a terrible commute with a driver who often gets angry with her for making him wait. He tells Wadjda's mother that he will no longer drive her to work, but Wadjda and Abdullah find where the driver lives and visit his house to tell him to take her mother's business. After Abdullah threatens to have his uncle deport the driver, he agrees.

Meanwhile, Wadjda's grandmother on her father's side is looking for a second wife for her son because Wadjda's mother cannot have any more children and Wadjda's uncle wants a son. Wadjda's mother is angry and scared by this, so she tries on a beautiful red dress for her brother-in-law's wedding to gain support and to "scare off" any potential women who may consider marrying him.

At school, Wadjda decides to join the religion club to participate in a Quran recital competition featuring a SR1,000 cash prize (equivalent of about US$270[12]). Meanwhile, two girls at the madrasa caught by the headmistress for adorning themselves with nail polish and marker-drawn ankle tattoos are surprised when Wadjda, in keeping with her new pious image, does not stand with them by testifying in their favor. Wadjda's efforts at memorization impress her teacher, and she wins the competition. The staff and students are shocked when Wadjda announces her intention to buy a bicycle with the prize money. The headmistress is furious, and instead donates the reward to Palestine against Wadjda's will.

Abdullah offers Wadjda his bike (which she does not accept) and says he wants to marry her when they are older. Wadjda returns home to find her father and begins crying when he says he is proud that she won the competition. After a brief conversation, he asks Wadjda to tell her mother that he loves her, and leaves the house to take a phone call. Later, Wadjda finds out that her father has taken a second wife as she joins her mother in viewing the wedding ceremony from their rooftop. Wadjda suggests that her mother could buy the red dress and win her father back again, but her mother reveals that she has instead spent the money on the green bike her daughter wants. The two hug as fireworks from the wedding light up the night sky behind them.

The next day, Wadjda rides down the street on her new bike. The owner of the bike shop sees her passing and smiles. She races Abdullah and wins.

- Reem Abdullah as Mother

- Waad Mohammed as Wadjda (وجدة)

- Abdullrahman Al Juhani as Abdullah

- Sultan Al Assaf as Father[13]

- Ahd Kamel as Ms Hussa (credited as Ahd)

- Ibrahim Al Mozael as Toyshop Owner

- Nouf Saad as Qu'ran Teacher

- Rafa Al Sanea as Fatima

- Alanoud Sajini as Fatin

- Rehab Ahmed as Noura

- Dana Abdullilah as Salma

- Mohammed Zahir as Iqbal – the Driver

According to the director Haifaa al-Mansour, it took five years to make Wadjda. She spent most of the time trying to find financial backing and getting filming permission, since she insisted on filming in Saudi Arabia for reasons of authenticity. She received backing from Rotana, the film production company of Prince Alwaleed bin Talal. However, she very much wanted to find a foreign co-producer because "in Saudi there are no movie theatres, there is no film industry to speak of and, therefore, little money for investment".[14] After her selection for a Sundance Institute writer's lab in Jordan, al-Mansour got in touch with the German production company Razor Film, which had previously produced films with Middle-Eastern topics (Paradise Now and Waltz with Bashir).[14] The production involved co-operation with two German public TV broadcasters, Norddeutscher Rundfunk and Bayerischer Rundfunk.[13] Additional funding came from Filmförderungsanstalt [de] (FFA, Berlin); Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg GmbH (MBB, Potsdam); Mitteldeutsche Medienförderung GmbH (MDM, Leipzig); and Filmfonds Babelsberg (ILB, Potsdam-Babelsberg).[13]

Al-Mansour's screenplay was influenced by neorealist cinema such as Vittorio De Sica's Bicycle Thieves, Jafar Panahi's Offside and the Dardenne brothers' Rosetta. The final scene recalls the final scene of François Truffaut's The 400 Blows. Al-Mansour says that the original version of her screenplay was much bleaker than the finished product: "I decided I didn't want the film to carry a slogan and scream, but just to create a story where people can laugh and cry a little."[14] Al-Mansour based the character of Wadjda on one of her nieces and also on her own experiences when growing up.[14] The main themes of the story are freedom, as represented by the bicycle, and the fear of emotional abandonment, as Wadjda's father wants to take a second wife who will provide him with a son.[14]

Wadjda was filmed on the streets of Riyadh, which often made it necessary for the director to work from the back of a van, as she could not publicly mix with the men in the crew. Often, she could only communicate via walkie-talkie and had to watch the actors on a monitor. This made it difficult to direct: "It made me realise the need to rehearse and to develop an understanding for each scene before we shot it."[14]

Waad Mohammed, who plays Wadjda, was a first-time actress.[14]

Wadjda received critical acclaim. The film-critics aggregate Rotten Tomatoes reported 99% of critics gave the film a positive review based on 122 reviews, with an average score of 8/10. The critical consensus is: "Transgressive in the best possible way, Wadjda presents a startlingly assured new voice from a corner of the globe where cinema has been all but silenced."[15] Metacritic, which assigns a standardized score out of 100, rated the film 81 based on 26 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[16]

Film critics cite the ways Wadjda is able to grapple with important societal issues, while also accurately understanding the limits of large scale change. New York Times film critic A.O. Scott states, "With impressive agility, Wadjda finds room to maneuver between harsh realism and a more hopeful kind of storytelling"; it accurately shows the immense challenges women face in Saudi Arabia, while also showing that there is room for change and growth.[17] The New Yorker film critic Anthony Lane feels similarly, as he argues that there are many ways Wadjda could have done more of a disservice to women in Saudi Arabia, rather than helping expose their inequality. He says that Wadjda strikes the right balance, in that it is enjoyable to watch, while also effective in calling for social change.[17][18]

Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post also reviewed the film positively, praising the story as well as the film’s attention to the “myriad visual and textural details of modern life in Saudi Arabia, a place of dun-colored monotony, cruelty and hypocrisy, as well as prosperity, deep devotion and poetry”.[19]

The film premiered at the Venice Film Festival in August 2012. It was released in Germany by Koch Media in 2013. Other distributors are: Pretty Pictures (France, theatrical), Sony Pictures Classics (USA, theatrical), Wild Bunch Benelux (Netherlands, theatrical), The Match Factory (Non-USA, all media) and Soda Pictures (UK, all media). It has been shown at several film festivals:

| Country | Release Date | Film Festival or full release | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 31 August 2012[20] | Venice Film Festival | |

| USA | 15 September 2012[20] | Telluride Film Festival | |

| Poland | 28 November 2012[20] | Filmy Swiata ale kino+ Festival | |

| Iceland | 29 November 2012[20] | Fully | |

| Italy | 6 December 2012[20] | Fully | |

| Netherlands | 26 January 2013[20] | International Film Festival Rotterdam | |

| Sweden | 30 January 2013[20] | Goteborg International Film Festival | |

| Belgium | 6 February 2013[20] | Fully | |

| France | 6 February 2013[20] | Fully | |

| Serbia | 23 February 2013[20] | Belgrade Film Festival | |

| Sweden | 8 March 2013[20] | Fully | |

| Netherlands | 16 May 2013[20] | Fully | |

| Spain | 21 June 2013 in festival,[21][22] as of 28 June 2013 at movie theaters[20] | Festival Internacional de Cinema de València – Cinema Jove (Valencia International Film Festival – Youth Cinema)[22][23] | |

| UK | 19 July 2013[14] | Fully | |

| Germany | 25 July 2013 | Fünf-Seen-Filmfestival[24] | |

| Germany | 15 August 2013[20] | Fully |

Other screenings include as the opening film of the 6th Gulf Film Festival in Dubai (11–17 April) and at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York (21/25 April).[14] The film was scheduled to be released on DVD in February 2014.[25]

| Awards | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result |

| Asia Pacific Screen Awards[26] | 12 December 2013 | Best Children's Feature Film | Nominated | |

| Alliance of Women Film Journalists[27] | 19 December 2013 | Best Non-English Language Film | Nominated | |

| This Year's Outstanding Achievement By a Woman in the Film Industry | Haaifa Al-Mansour for challenging the limitations placed on women within her culture.[27] | Won | ||

| British Film Institute | 20 October 2012 | Sutherland Trophy | Haifaa Al-Mansour | Nominated |

| Dubai International Film Festival[6] | 18 December 2012 | Muhr Arab Award | Waad Mohammed (Best Actress – Feature)Roman Paul (Best Film – Feature)Gerhard Meixner (Best Film – Feature) | Won |

| Fribourg International Film Festival | 23 March 2013 | Grand Prix | Haifaa Al-Mansour | Nominated |

| Innsbruck International Film Festival | 1 June 2013 | Südwind-Filmpreis | Haifaa Al-Mansour | Won |

| Motion Picture Sound Editors Golden Reel Awards[28][29] | 16 February 2014 | Best Sound Editing: Sound Effects, Foley, Dialogue & ADR in a Foreign Feature Film | Sebastian Schmidt | Nominated |

| National Board of Review | 4 December 2013 | NBR Freedom of Expression | Haifaa Al-Mansour | Won |

| Palm Springs International Film Festival | 13 January 2014 | Directors to Watch | Haifaa Al-Mansour | Won |

| Rotterdam International Film Festival | 2 February 2013 | Dioraphte Award | Haifaa Al-Mansour | Won |

| San Francisco Film Critics Circle[30] | 15 December 2013 | Best Foreign Language Film | Nominated | |

| Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival | 27 November 2012 | Don Quixote Award | Haifaa Al-Mansour | Special Mention |

| Netpac Award | Special Mention | |||

| Grand Prize | Nominated | |||

| Vancouver International Film Festival[31] | 12 October 2013 | Most Popular International First Feature Award | Haifaa Al-Mansour | Won |

| Venice Film Festival | 8 September 2012 | CinemAvvenire Award | Haifaa Al-Mansour (Best Film—Il cerchio non è rotondo Award) | |

| C.I.C.A.E. Award | Haifaa Al-Mansour | |||

| Interfilm Award | ||||

| British Academy Film Awards | 16 February 2014 | Best Foreign Film | Haifaa Al-Mansour, Gerhard Meixner, Roman Paul | Nominated |

- Women and bicycling in Islam

- Cinema of Saudi Arabia

- List of Saudi Arabian films

- List of submissions to the 86th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Saudi Arabian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

- ^ "Wadjda (2012) – Financial Information".

- ^ "Cannes 2012: Saudi Arabia's First Female Director Brings 'Wadjda' to Fest". The Hollywood Reporter. 15 May 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ "Saudi's first female director seeks to break gender taboos". TimesLIVE. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ Macnab, Geoffrey (15 May 2012). "Al Mansour reveals struggles of directing Wadjda". Screen Daily. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ "First film shot in Saudi to debut at Cannes". Arabian Business. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Dubai International Film Festival". Dubaifilmfest.com. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ "Wadjda". Euronews. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ "Oscars: Saudi Arabia Nominates 'Wadjda' for Foreign Language Category". The Hollywood Reporter. 13 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Oscars: Saudi Arabia Taps 'Wadjda' As First Foreign-Language Entry". Variety. 13 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "'Wadjda' is Saudi Arabia's first nominee for foreign-language Oscar". LA Times. 13 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia submits first film for Oscars with 'Wadjda'". Gulf News. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "1 Saudi Riyal equals 0.27 US Dollar". xe.com. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ a b c "Filmportal: Wadjda". Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Grey, Tobias (30–31 March 2013), "The undercover director", Financial Times, p. 14

- ^ "Wadjda – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Wadjda Reviews – Metacritic". Metacritic. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ a b Scott, A. O. (12 September 2013). "Silly Girl, You Want to Race a Boy?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Lane, Anthony (9 September 2013). "How They Roll". The New Yorker. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann (19 September 2013). "'Wadjda' review". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n IMDB:Wadjda (2012)

- ^ "La bicileta verde", Luis Tormo, Encadenados, Revista de Cine, 28 June 2013 (in Spanish). [Consulted 23 May 2018].

- ^ a b "La primera directora de cine saudí estrena en España", HoyEsArte.com, 5 June 2013 (in Spanish). [Consulted 23 May 2018].

- ^ "Haifaa Al Mansour, rompedora cineasta saudí. Su película ‘La bicicleta verde’ fue el primer filme rodado en Arabia Saudí, donde las salas de cine están prohibidas", Rocío Ayuso, El País, 22 June 2013 (in Spanish). [Consulted 23 May 2018].

- ^ "Fünf-Seen-Filmfestival" (in German). Fsff.de. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ Fielding-Smith, Abigail (14–15 December 2013), "The film director blazing a trail for Saudi women", Financial Times, p. 21

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 2013". asiapacificscreenacademy.com. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ a b "2013 EDA Award Nominess". Alliance of Women Film Journalists. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Walsh, Jason (15 January 2014). "Sound Editors Announce 2013 Golden Reel Nominees". Variety. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "'Gravity' and '12 Years a Slave' lead MPSE Golden Reel Awards nominations". HitFix. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Stone, Sasha (13 December 2013). "San Francisco Film Critics Nominations". Awards Daily. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ "Final Award Winners Announced & Closing Remarks". Vancouver International Film Festival. 12 October 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- Official website

- Wadjda on Facebook

- Wadjda at IMDb

- Wadjda at Box Office Mojo

- Wadjda at Rotten Tomatoes

- Wadjda at Metacritic