Waterloo Bridge (1940 film) (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1940 film by Mervyn LeRoy

| Waterloo Bridge | |

|---|---|

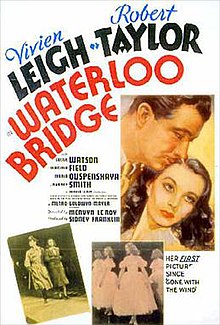

Original film poster Original film poster |

|

| Directed by | Mervyn LeRoy |

| Written by | S. N. BehrmanHans RameauGeorge Froeschel |

| Based on | _Waterloo Bridge_1930 playby Robert E. Sherwood |

| Produced by | Sidney Franklin |

| Starring | Vivien LeighRobert Taylor Lucile WatsonVirginia FieldMaria OuspenskayaC. Aubrey Smith |

| Cinematography | Joseph Ruttenberg |

| Music by | Herbert Stothart |

| Productioncompany | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

| Distributed by | Loew's Inc. |

| Release date | May 17, 1940 (1940-05-17) |

| Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.2 million |

| Box office | $2.5 million |

Vivien Leigh and Lucile Watson

Waterloo Bridge is a 1940 American drama film and the remake of the 1931 film also called Waterloo Bridge, adapted from the 1930 play Waterloo Bridge. In an extended flashback narration, it recounts the story of a dancer and an army captain who meet by chance on Waterloo Bridge in London. The film was made by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, directed by Mervyn LeRoy and produced by Sidney Franklin and Mervyn LeRoy. The screenplay is by S. N. Behrman, Hans Rameau and George Froeschel, based on the Broadway drama by Robert E. Sherwood. The music is by Herbert Stothart and cinematography by Joseph Ruttenberg.

The film stars Robert Taylor and Vivien Leigh. It was a success at the box office and nominated for two Academy Awards: Best Music for Herbert Stothart and Best Cinematography. It was also considered a personal favorite by both Leigh and Taylor.

In 1956, it was remade again as Gaby, which stars Leslie Caron and John Kerr.

After Britain's declaration of war in World War II, army colonel Roy Cronin is driven to London's Waterloo station on his way to France, and briefly alights on Waterloo Bridge to reminisce about events that occurred during World War I when he met Myra Lester, whom he had planned to marry. While Roy gazes at a good-luck charm, a billiken that she had given him, the story unfolds.

Roy, a captain in the Rendleshire Fusiliers on his way to the front, and Myra, a ballerina, serendipitously meet crossing Waterloo Bridge during an air raid, striking up an immediate rapport while taking shelter. Myra invites Roy to attend that evening's ballet performance and an enamored Roy ignores an obligatory dinner with his colonel. Roy sends a note to Myra to join him after the performance, but the note is intercepted by the mistress of the ballet troupe, the tyrannical Madame Olga, who forbids Myra from having any relationship with Roy. Despite the admonition, they meet at a romantic night spot. Roy has to travel to the front immediately and proposes marriage, but wartime circumstances prevent them from marrying immediately. Roy assures Myra that his family will look after her while he is away. Madame Olga learns of Myra's disobedience and dismisses her from the troupe along with fellow dancer Kitty when she scolds Olga for spoiling Myra's happiness.

The young women share a small flat. Unable to find work, they soon become penniless. Roy's mother Lady Margaret Cronin and Myra arrange to meet for an introduction. Awaiting Lady Margaret's belated arrival at a tearoom, Myra scans a newspaper and faints after finding Roy listed among the war dead. Shocked and bewildered, Myra is offered a tall brandy by the receptionist to help bring her around. Sitting alone, Myra swallows a large amount of brandy just as Lady Margaret appears. Unable to disclose the dreadful news, Myra's banal and incoherent conversation is unsettling to her prospective mother-in-law, who withdraws without seeking further explanation. Myra faints again and falls ill with grief. The two young ladies’ economic situation becomes dire. To cover their expenses, her flatmate Kitty becomes a streetwalker. Myra believed that Kitty was working as a stage performer but then learns what her friend has done. Feeling that she has alienated Lady Margaret and having no desire to live, the heartbroken Myra joins her friend Kitty and resorts to prostitution as well. A year passes.

While offering herself to soldiers on leave arriving at Waterloo Station, Myra sees Roy, who is alive and well. He had been wounded and held as a prisoner of war. A reconciliation occurs that is joyous for Roy but bittersweet for Myra. The couple travel to the family estate in Scotland to visit Lady Margaret, who deduces the misunderstanding that occurred at the tearoom. Myra is also accepted by Roy's uncle, the Duke, but he inadvertently feeds her guilt by saying that she could never do anything to bring shame or dishonour to the family. Confronted with the possibility of a scandal and the seeming impossibility of a happy marriage, Myra decides that breaking off the engagement is her only choice. Myra discloses the truth to a compassionate Lady Margaret but is unable to believe herself worthy of marrying Roy. Myra leaves behind a goodbye note and returns to London. Roy follows, with the aid of Kitty, hoping to find her despite discovering the truth in the process. Myra is depressed and returns to Waterloo Bridge, where she commits suicide by walking into the path of an oncoming truck.

In the present day, the older Roy reminisces about Myra's sincere final profession of love that was only for him and no other. He tucks her charm into his coat pocket and gets driven away in his car.

- Vivien Leigh as Myra Lester

- Robert Taylor as Roy Cronin

- Virginia Field as Kitty Meredith

- Maria Ouspenskaya as Madame Olga Kirowa

- C. Aubrey Smith as The Duke

- Lucile Watson as Lady Margaret Cronin

- Janet Shaw as Maureen

- Janet Waldo as Elsa

- Steffi Duna as Lydia

- Virginia Carroll as Sylvia

- Leda Nicova as Marie

- Florence Baker as Beatrice

- Margery Manning as Mary

- Frances MacInerney as Violet

- Eleanor Stewart as Grace

- Gilbert Emery as Colonel (uncredited)

- Halliwell Hobbes as Vicar (uncredited)

- Harry Stubbs as Proprietor (uncredited)

MGM bought the 1931 version of Waterloo Bridge from Universal Studios in order to produce the remake. From its initial release, the 1931 film had been censored in major American cities because of objections to the portrayal of prostitution. The censorship was imposed first by local authorities, such as a Chicago police censorship board, before enforcement by the Hays Office in 1934 made it impossible to exhibit the film anywhere in the United States.

Prostitution is a subject that neither our Ordinance nor Commissioner Alcock permits us to leave in pictures whether for an adult or a general permit. It is a clear violation of all our standards and also, we had understood, a violation of the underlying purpose of the [Motion Picture Production] Code.

— Chicago police censorship board, 1931[1]

Because of the Motion Picture Production Code, which had not been in effect when the 1931 film version was made, plot details of the 1940 version were significantly changed and somewhat sanitized. In the original play and film, based on Sherwood's personal experiences, both characters are Americans; Myra is an unemployed chorus girl who has turned to prostitution and Roy is a callow 19-year-old expatriate who does not realize how she makes money. However, in the 1940 version, both are British, Myra a promising ballerina in a prestigious dance company who becomes a prostitute only after believing that her sweetheart has been killed and Roy a mature officer of Scottish nobility. In the original film, Myra is accidentally killed after her situation with Roy has apparently been happily resolved; in the 1940 version, she commits suicide when her inner conflict becomes insurmountable.[2] The flashback format of the 1940 version was a device added in acknowledgment of the recent onset of war when the script was written in 1939.

Waterloo Bridge capitalized on Leigh's success the previous year in Gone with the Wind. Taylor was eager to show audiences that he was more than the suave and youthful lover whom he had played in such films as Camille and Three Comrades. Leigh wanted Laurence Olivier for the role of Roy Cronin and was unhappy that Taylor had been cast in the part, although she had enjoyed him on the set of A Yank at Oxford.[3] She wrote to her husband Leigh Holman: "Robert Taylor is the man in the picture, and as it was written for Larry, it's a typical piece of miscasting. I am afraid it will be a dreary job ..." Taylor later said of his performance: "It was the first time I really gave a performance that met the often unattainable standards I was always setting for myself." Of Leigh, Taylor said, "Miss Leigh was simply great in her role, and she made me look better." Of all her films, Leigh stated Waterloo Bridge was her favorite.[4] Taylor also named the film as his personal favorite.

Ethel Griffies and Rita Carlisle (then Carlyle), cast respectively in the 1931 film as Myra's landlady and a woman on the bridge when they meet, appear in the 1940 version in similar roles.

Waterloo Bridge opened in New York and shortly after in London to positive reviews.[5]

In a contemporary review for The New York Times, critic Bosley Crowther was effusive in his praise for Vivien Leigh: "Let there be no doubt about it. Vivien Leigh is as fine an actress as we have on the screen today. Maybe even the finest, and that's a lot to say. Plenty of skeptics are still mumbling that her Scarlett O'Hara was a freak, that any one could have played it with such a wide-open field. We know all about them—and we know, too, about the unreconstructed dissidents. So this is an urgent hint that they ... see this remarkable Miss Leigh in her first picture since 'Gone With the Wind.' If they are not then convinced, we will cover ourself with a sack."[6]

When the film was released in China in November 1940, it was enormously popular. As a result, the story became a standard of Shanghai opera and the song "Auld Lang Syne" became widely known in China.[7][8]

The film was nominated by the American Film Institute for inclusion in its 2002 list AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions.[9]

According to MGM records, the film earned 1,250,000intheU.S.andCanadaand1,250,000 in the U.S. and Canada and 1,250,000intheU.S.andCanadaand1,217,000 elsewhere, resulting in a profit of $491,000.[10]

Waterloo Bridge was dramatized as a half-hour radio play on two broadcasts of The Screen Guild Theater, the first on January 12, 1941 with Brian Aherne and Joan Fontaine and the second on September 9, 1946 with Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Taylor. It was also presented as a half-hour broadcast of Screen Directors Playhouse on September 28, 1951 with Norma Shearer.

Citations

- ^ Campbell, R. "Prostitution and film censorship in the USA." Archived 2012-12-13 at the Wayback Machine La Trobe University, Melbourne, December 1997.

- ^ Walker 1987, p. 138.

- ^ Taylor 1984, p. 76.

- ^ Bean 2013, p. 71.

- ^ Capus 2003, p. 71.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (1940-05-17). "The Screen in Review". The New York Times. p. 23.

- ^ Patience, Martin (31 December 2013). "How Auld Lang Syne stormed China". BBC News. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ Lingyan, Cao (17 July 2019). "How 'Waterloo Bridge' Helped Birth a New Brand of Shanghai Opera". Sixthtone. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ "The Eddie Mannix Ledger." Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study, Los Angeles.

Bibliography

Bean, Kendra. Vivien Leigh: An Intimate Portrait. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7624-5099-2.

Capus, Michelangelo. Vivien Leigh: A Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7864-1497-0.

Taylor, John Russell. Vivien Leigh. London: Elm Tree Books, 1984. ISBN 0-241-11333-4.

Vickers, Hugo. Vivien Leigh: A Biography. London: Little, Brown and Company, 1988 edition. ISBN 978-0-33031-166-3.

Walker, Alexander. Vivien: The Life of Vivien Leigh. New York: Grove Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8021-3259-6.

Streaming audio

- "One of the most beautiful plays and motion pictures of all time" on Screen Guild Theater: January 12, 1941

- Broadcast featuring Robert Taylor, star of the 1940 film, on Screen Guild Theater: September 9, 1946

- "MGM's screenplay of Robert Sherwood's drama" on Screen Directors Playhouse: September 28, 1951