William R. Boggs (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

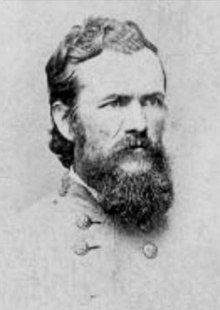

| William R. Boggs | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Birth name | William Robertson Boggs |

| Born | (1829-03-18)March 18, 1829Augusta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | September 11, 1911(1911-09-11) (aged 82)Winston-Salem, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Buried | Salem Cemetery,Winston-Salem, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United StatesConfederate States |

| Service / branch | United States ArmyConfederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1853–1861 (U.S.)1861–1865 (C.S.) |

| Rank | First Lieutenant (U.S.) Brigadier General (C.S.) |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

Brigadier-General William Robertson Boggs (March 18, 1829 – September 11, 1911) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He was noted as a military engineer who constructed the fortifications that protected some of the Confederacy's most important seaports.

Early life and education

[edit]

Boggs, son of Archibald & Mary Ann (Robertson) Boggs, was born in Augusta, Georgia. Comparatively little is known of his early youth, but it is known he studied at the Augusta Academy.[1] Two of his brothers would also serve in the Confederate Army. They spent their summers at the Sand Hills near what is now Summerville, South Carolina, a popular tourist resort. At the age of twenty in July 1849, he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point as a cadet from Georgia. He graduated four years later among the first five in his class. Among Boggs' classmates were James B. McPherson, Philip H. Sheridan, and John M. Schofield, later Union generals, and John Bell Hood of the Confederate service.

On graduation he was brevetted as a second lieutenant and assigned to the Topographical Bureau. He spent some time in the office of the Pacific Railroad Surveys. In 1854 he was transferred to the Ordnance Corps and was made assistant at the Watervliet Arsenal in Troy, New York. In December of the same year he became second lieutenant and in 1856 he was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant. While at Watervliet Arsenal, on December 19, 1855, he married Mary Sophia, daughter of Col. John Symington, the commandant. To them were born five children–William R., Jr., a mining engineer who was murdered in Mexico in 1907; Elizabeth McCaw, John Symington, Edith Allston, and Henry Patterson Boggs.[2] (For some unknown reason a sixth child, Archibald Boggs (1860–1881) was omitted from the biographical data published for General Boggs.)

In 1857 Boggs was transferred to the Louisiana Arsenal at Baton Rouge, Louisiana. In 1859 he became inspector of ordnance at Point Isobel, Texas. On December 14, 1859, he took part in an engagement with Cortina's Mexican marauders near Fort Brown, for which he was given honorable mention by General Winfield Scott. Soon after, he was transferred to the Alleghany Arsenal at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to which his father-in-law Colonel Symington had also been assigned.[3]

Boggs resigned from the U.S. Army the very day that the Georgia Convention adopted its ordinance of secession.[4] However, his father-in-law stayed in the Federal service. Early in the war, Boggs was appointed by Governor Joseph E. Brown as the purchasing agent to procure arms, ammunition, and supplies for Georgia's state troops. Later, in the Provisional Confederate Army, Boggs' duties were again as an engineer and ordnance officer, given primarily to staff duty for such officers as Braxton Bragg. He was never given the command of troops in combat, although he commanded all engineers and artillery in Pensacola, Florida. His major accomplishments were to perfect and complete fortifications and supply depots in 1861 (including the defenses of Charleston, South Carolina, and Pensacola); to engineer Kirby Smith's invasion of Kentucky in 1862; and to assist Smith's military administration west of the Mississippi River from 1863 to 1865.[5]

In 1862, he was appointed colonel, Chief Engineer of the State of Georgia. In recognition of his efforts in constructing the fortifications that defended Savannah, Georgia, one of the earthworks was named Fort Boggs. During the Kentucky campaign, Colonel Boggs, by then back in the Confederate national service, won the confidence of his superiors. On General Kirby Smith's recommendation, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general and became chief of staff under him in the Trans-Mississippi Department in the spring of 1863.[6] Late in the war, Boggs resigned after a quarrel with Smith. For a short time thereafter, he commanded the District of Louisiana, but was soon superseded by Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays and he subsequently awaited orders at Shreveport, Louisiana.

Early in 1865 he enlisted in an expedition to enter military service in Mexico. Finding that the purpose of its leaders was to fight for Maximilian, rather than Juarez, he withdrew his name and returned to the Confederate army. With the collapse of the Confederate armies in the East, Kirby Smith moved his headquarters to Houston, Texas. The surrender of his army was made by Smith's subordinates, in which General Boggs participated, the parole of Boggs being dated June 9, 1865.[7]

Boggs in later life

After the war, Boggs engaged in the profession of engineering, participating to a great extent in railroad construction in the West. In 1875, he was appointed Professor of Mechanics in the Virginia Polytechnic Institute at Blacksburg, a position he held until a reorganization of the faculty in 1881. One of his colleagues wrote, "He was highly valued by his associates as a man of force and culture; was esteemed by the student body as an attractive and honest teacher; by the people of the community as an upright, genial, agreeable gentleman. Politics was alone responsible for his removal."[8]

The later years of his life were spent in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where he died at the age of eighty-two. He was buried in Salem Cemetery.[9]

One of his nephews, Major Archibald Butt, perished in the sinking of the RMS Titanic.[10]

- ^ Boggs, p. ix.

- ^ Boggs, pp. xxii-xxiii.

- ^ Boggs, p. xi.

- ^ Boggs, p. xii.

- ^ Boggs, pp. xii-xiii.

- ^ Boggs, p. xix.

- ^ Boggs, p. xxi.

- ^ Boggs, p. xxii.

- ^ Civil War High Commands

- ^ Boggs, p. viii.

- Boggs, William R., Military Reminiscences of Gen. Wm. R. Boggs, C.S.A. Durham, North Carolina: The Seeman Printery, 1913.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Letter from Brig. Gen. W. R. Boggs to Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor, from the Edmund Kirby-Smith Papers, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Military Reminiscences of Gen. Wm. R. Boggs, C.S.A. Durham, N.C.: The Seeman Printery, 1913.

- The William Robertson Boggs Family Papers

- William R. Boggs at Find a Grave

- William Robertson Boggs Letter, Special Collections at The University of Southern Mississippi (Historical Manuscripts)